Naming Scheme for Hadrons 1 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Five Common Particles

The Five Common Particles The world around you consists of only three particles: protons, neutrons, and electrons. Protons and neutrons form the nuclei of atoms, and electrons glue everything together and create chemicals and materials. Along with the photon and the neutrino, these particles are essentially the only ones that exist in our solar system, because all the other subatomic particles have half-lives of typically 10-9 second or less, and vanish almost the instant they are created by nuclear reactions in the Sun, etc. Particles interact via the four fundamental forces of nature. Some basic properties of these forces are summarized below. (Other aspects of the fundamental forces are also discussed in the Summary of Particle Physics document on this web site.) Force Range Common Particles It Affects Conserved Quantity gravity infinite neutron, proton, electron, neutrino, photon mass-energy electromagnetic infinite proton, electron, photon charge -14 strong nuclear force ≈ 10 m neutron, proton baryon number -15 weak nuclear force ≈ 10 m neutron, proton, electron, neutrino lepton number Every particle in nature has specific values of all four of the conserved quantities associated with each force. The values for the five common particles are: Particle Rest Mass1 Charge2 Baryon # Lepton # proton 938.3 MeV/c2 +1 e +1 0 neutron 939.6 MeV/c2 0 +1 0 electron 0.511 MeV/c2 -1 e 0 +1 neutrino ≈ 1 eV/c2 0 0 +1 photon 0 eV/c2 0 0 0 1) MeV = mega-electron-volt = 106 eV. It is customary in particle physics to measure the mass of a particle in terms of how much energy it would represent if it were converted via E = mc2. -

Fundamentals of Particle Physics

Fundamentals of Par0cle Physics Particle Physics Masterclass Emmanuel Olaiya 1 The Universe u The universe is 15 billion years old u Around 150 billion galaxies (150,000,000,000) u Each galaxy has around 300 billion stars (300,000,000,000) u 150 billion x 300 billion stars (that is a lot of stars!) u That is a huge amount of material u That is an unimaginable amount of particles u How do we even begin to understand all of matter? 2 How many elementary particles does it take to describe the matter around us? 3 We can describe the material around us using just 3 particles . 3 Matter Particles +2/3 U Point like elementary particles that protons and neutrons are made from. Quarks Hence we can construct all nuclei using these two particles -1/3 d -1 Electrons orbit the nuclei and are help to e form molecules. These are also point like elementary particles Leptons We can build the world around us with these 3 particles. But how do they interact. To understand their interactions we have to introduce forces! Force carriers g1 g2 g3 g4 g5 g6 g7 g8 The gluon, of which there are 8 is the force carrier for nuclear forces Consider 2 forces: nuclear forces, and electromagnetism The photon, ie light is the force carrier when experiencing forces such and electricity and magnetism γ SOME FAMILAR THE ATOM PARTICLES ≈10-10m electron (-) 0.511 MeV A Fundamental (“pointlike”) Particle THE NUCLEUS proton (+) 938.3 MeV neutron (0) 939.6 MeV E=mc2. Einstein’s equation tells us mass and energy are equivalent Wave/Particle Duality (Quantum Mechanics) Einstein E -

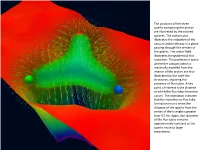

The Positons of the Three Quarks Composing the Proton Are Illustrated

The posi1ons of the three quarks composing the proton are illustrated by the colored spheres. The surface plot illustrates the reduc1on of the vacuum ac1on density in a plane passing through the centers of the quarks. The vector field illustrates the gradient of this reduc1on. The posi1ons in space where the vacuum ac1on is maximally expelled from the interior of the proton are also illustrated by the tube-like structures, exposing the presence of flux tubes. a key point of interest is the distance at which the flux-tube formaon occurs. The animaon indicates that the transi1on to flux-tube formaon occurs when the distance of the quarks from the center of the triangle is greater than 0.5 fm. again, the diameter of the flux tubes remains approximately constant as the quarks move to large separaons. • Three quarks indicated by red, green and blue spheres (lower leb) are localized by the gluon field. • a quark-an1quark pair created from the gluon field is illustrated by the green-an1green (magenta) quark pair on the right. These quark pairs give rise to a meson cloud around the proton. hEp://www.physics.adelaide.edu.au/theory/staff/leinweber/VisualQCD/Nobel/index.html Nucl. Phys. A750, 84 (2005) 1000000 QCD mass 100000 Higgs mass 10000 1000 100 Mass (MeV) 10 1 u d s c b t GeV HOW does the rest of the proton mass arise? HOW does the rest of the proton spin (magnetic moment,…), arise? Mass from nothing Dyson-Schwinger and Lattice QCD It is known that the dynamical chiral symmetry breaking; namely, the generation of mass from nothing, does take place in QCD. -

Particle Physics Dr Victoria Martin, Spring Semester 2012 Lecture 12: Hadron Decays

Particle Physics Dr Victoria Martin, Spring Semester 2012 Lecture 12: Hadron Decays !Resonances !Heavy Meson and Baryons !Decays and Quantum numbers !CKM matrix 1 Announcements •No lecture on Friday. •Remaining lectures: •Tuesday 13 March •Friday 16 March •Tuesday 20 March •Friday 23 March •Tuesday 27 March •Friday 30 March •Tuesday 3 April •Remaining Tutorials: •Monday 26 March •Monday 2 April 2 From Friday: Mesons and Baryons Summary • Quarks are confined to colourless bound states, collectively known as hadrons: " mesons: quark and anti-quark. Bosons (s=0, 1) with a symmetric colour wavefunction. " baryons: three quarks. Fermions (s=1/2, 3/2) with antisymmetric colour wavefunction. " anti-baryons: three anti-quarks. • Lightest mesons & baryons described by isospin (I, I3), strangeness (S) and hypercharge Y " isospin I=! for u and d quarks; (isospin combined as for spin) " I3=+! (isospin up) for up quarks; I3="! (isospin down) for down quarks " S=+1 for strange quarks (additive quantum number) " hypercharge Y = S + B • Hadrons display SU(3) flavour symmetry between u d and s quarks. Used to predict the allowed meson and baryon states. • As baryons are fermions, the overall wavefunction must be anti-symmetric. The wavefunction is product of colour, flavour, spin and spatial parts: ! = "c "f "S "L an odd number of these must be anti-symmetric. • consequences: no uuu, ddd or sss baryons with total spin J=# (S=#, L=0) • Residual strong force interactions between colourless hadrons propagated by mesons. 3 Resonances • Hadrons which decay due to the strong force have very short lifetime # ~ 10"24 s • Evidence for the existence of these states are resonances in the experimental data Γ2/4 σ = σ • Shape is Breit-Wigner distribution: max (E M)2 + Γ2/4 14 41. -

Fully Strange Tetraquark Sss¯S¯ Spectrum and Possible Experimental Evidence

PHYSICAL REVIEW D 103, 016016 (2021) Fully strange tetraquark sss¯s¯ spectrum and possible experimental evidence † Feng-Xiao Liu ,1,2 Ming-Sheng Liu,1,2 Xian-Hui Zhong,1,2,* and Qiang Zhao3,4,2, 1Department of Physics, Hunan Normal University, and Key Laboratory of Low-Dimensional Quantum Structures and Quantum Control of Ministry of Education, Changsha 410081, China 2Synergetic Innovation Center for Quantum Effects and Applications (SICQEA), Hunan Normal University, Changsha 410081, China 3Institute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 4University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China (Received 21 August 2020; accepted 5 January 2021; published 26 January 2021) In this work, we construct 36 tetraquark configurations for the 1S-, 1P-, and 2S-wave states, and make a prediction of the mass spectrum for the tetraquark sss¯s¯ system in the framework of a nonrelativistic potential quark model without the diquark-antidiquark approximation. The model parameters are well determined by our previous study of the strangeonium spectrum. We find that the resonances f0ð2200Þ and 2340 2218 2378 f2ð Þ may favor the assignments of ground states Tðsss¯s¯Þ0þþ ð Þ and Tðsss¯s¯Þ2þþ ð Þ, respectively, and the newly observed Xð2500Þ at BESIII may be a candidate of the lowest mass 1P-wave 0−þ state − 2481 0þþ 2440 Tðsss¯s¯Þ0 þ ð Þ. Signals for the other ground state Tðsss¯s¯Þ0þþ ð Þ may also have been observed in PC −− the ϕϕ invariant mass spectrum in J=ψ → γϕϕ at BESIII. The masses of the J ¼ 1 Tsss¯s¯ states are predicted to be in the range of ∼2.44–2.99 GeV, which indicates that the ϕð2170Þ resonance may not be a good candidate of the Tsss¯s¯ state. -

Qt7r7253zd.Pdf

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title RELATIVISTIC QUARK MODEL BASED ON THE VENEZIANO REPRESENTATION. II. GENERAL TRAJECTORIES Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7r7253zd Author Mandelstam, Stanley. Publication Date 1969-09-02 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Submitted to Physical Review UCRL- 19327 Preprint 7. z RELATIVISTIC QUARK MODEL BASED ON THE VENEZIANO REPRESENTATION. II. GENERAL TRAJECTORIES RECEIVED LAWRENCE RADIATION LABORATORY Stanley Mandeistam SEP25 1969 September 2, 1969 LIBRARY AND DOCUMENTS SECTiON AEC Contract No. W7405-eng-48 TWO-WEEK LOAN COPY 4 This is a Library Circulating Copy whIch may be borrowed for two weeks. for a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Dlvislon, Ext. 5545 I C.) LAWRENCE RADIATION LABORATOR SLJ-LJ UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA BERKELET DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. -

Hadrons and Nuclei Abstract

Hadrons and Nuclei William Detmold (editor),1 Robert G. Edwards (editor),2 Jozef J. Dudek,2, 3 Michael Engelhardt,4 Huey-Wen Lin,5 Stefan Meinel,6, 7 Kostas Orginos,2, 3 and Phiala Shanahan1 (USQCD Collaboration) 1Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2Jefferson Lab 3College of William and Mary 4New Mexico State University 5Michigan State University 6University of Arizona 7RIKEN BNL Research Center Abstract This document is one of a series of whitepapers from the USQCD collaboration. Here, we discuss opportunities for lattice QCD calculations related to the structure and spectroscopy of hadrons and nuclei. An overview of recent lattice calculations of the structure of the proton and other hadrons is presented along with prospects for future extensions. Progress and prospects of hadronic spectroscopy and the study of resonances in the light, strange and heavy quark sectors is summarized. Finally, recent advances in the study of light nuclei from lattice QCD are addressed, and the scope of future investigations that are currently envisioned is outlined. 1 CONTENTS Executive summary3 I. Introduction3 II. Hadron Structure4 A. Charges, radii, electroweak form factors and polarizabilities4 B. Parton Distribution Functions5 1. Moments of Parton Distribution Functions6 2. Quasi-distributions and pseudo-distributions6 3. Good lattice cross sections7 4. Hadronic tensor methods8 C. Generalized Parton Distribution Functions8 D. Transverse momentum-dependent parton distributions9 E. Gluon aspects of hadron structure 11 III. Hadron Spectroscopy 13 A. Light hadron spectroscopy 14 B. Heavy quarks and the XYZ states 20 IV. Nuclear Spectroscopy, Interactions and Structure 21 A. Nuclear spectroscopy 22 B. Nuclear Structure 23 C. Nuclear interactions 26 D. -

Pos(LATTICE2014)106 ∗ [email protected] Speaker

Flavored tetraquark spectroscopy PoS(LATTICE2014)106 Andrea L. Guerrieri∗ Dipartimento di Fisica and INFN, Università di Roma ’Tor Vergata’ Via della Ricerca Scientifica 1, I-00133 Roma, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Mauro Papinutto, Alessandro Pilloni, Antonio D. Polosa Dipartimento di Fisica and INFN, ’Sapienza’ Università di Roma P.le Aldo Moro 5, I-00185 Roma, Italy Nazario Tantalo CERN, PH-TH, Geneva, Switzerland and Dipartimento di Fisica and INFN, Università di Roma ’Tor Vergata’ Via della Ricerca Scientifica 1, I-00133 Roma, Italy The recent confirmation of the charged charmonium like resonance Z(4430) by the LHCb ex- periment strongly suggests the existence of QCD multi quark bound states. Some preliminary results about hypothetical flavored tetraquark mesons are reported. Such states are particularly amenable to Lattice QCD studies as their interpolating operators do not overlap with those of ordinary hidden-charm mesons. The 32nd International Symposium on Lattice Field Theory, 23-28 June, 2014 Columbia University New York, NY ∗Speaker. c Copyright owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike Licence. http://pos.sissa.it/ Flavored tetraquark spectroscopy Andrea L. Guerrieri 1. Introduction The recent confirmation of the charged resonant state Z(4430) by LHCb [1] strongly suggests the existence of genuine compact tetraquark mesons in the QCD spectrum. Among the many phenomenological models, it seems that only the diquark-antidiquark model in its type-II version can accomodate in a unified description the puzzling spectrum of the exotics [2]. Although diquark- antidiquark model has success in describing the observed exotic spectrum, it also predicts a number of unobserved exotic partners. -

First Determination of the Electric Charge of the Top Quark

First Determination of the Electric Charge of the Top Quark PER HANSSON arXiv:hep-ex/0702004v1 1 Feb 2007 Licentiate Thesis Stockholm, Sweden 2006 Licentiate Thesis First Determination of the Electric Charge of the Top Quark Per Hansson Particle and Astroparticle Physics, Department of Physics Royal Institute of Technology, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden Stockholm, Sweden 2006 Cover illustration: View of a top quark pair event with an electron and four jets in the final state. Image by DØ Collaboration. Akademisk avhandling som med tillst˚and av Kungliga Tekniska H¨ogskolan i Stock- holm framl¨agges till offentlig granskning f¨or avl¨aggande av filosofie licentiatexamen fredagen den 24 november 2006 14.00 i sal FB54, AlbaNova Universitets Center, KTH Partikel- och Astropartikelfysik, Roslagstullsbacken 21, Stockholm. Avhandlingen f¨orsvaras p˚aengelska. ISBN 91-7178-493-4 TRITA-FYS 2006:69 ISSN 0280-316X ISRN KTH/FYS/--06:69--SE c Per Hansson, Oct 2006 Printed by Universitetsservice US AB 2006 Abstract In this thesis, the first determination of the electric charge of the top quark is presented using 370 pb−1 of data recorded by the DØ detector at the Fermilab Tevatron accelerator. tt¯ events are selected with one isolated electron or muon and at least four jets out of which two are b-tagged by reconstruction of a secondary decay vertex (SVT). The method is based on the discrimination between b- and ¯b-quark jets using a jet charge algorithm applied to SVT-tagged jets. A method to calibrate the jet charge algorithm with data is developed. A constrained kinematic fit is performed to associate the W bosons to the correct b-quark jets in the event and extract the top quark electric charge. -

Searching for a Heavy Partner to the Top Quark

SEARCHING FOR A HEAVY PARTNER TO THE TOP QUARK JOSEPH VAN DER LIST 5e Abstract. We present a search for a heavy partner to the top quark with charge 3 , where e is the electron charge. We analyze data from Run 2 of the Large Hadron Collider at a center of mass energy of 13 TeV. This data has been previously investigated without tagging boosted top quark (top tagging) jets, with a data set corresponding to 2.2 fb−1. Here, we present the analysis at 2.3 fb−1 with top tagging. We observe no excesses above the standard model indicating detection of X5=3 , so we set lower limits on the mass of X5=3 . 1. Introduction 1.1. The Standard Model One of the greatest successes of 20th century physics was the classification of subatomic particles and forces into a framework now called the Standard Model of Particle Physics (or SM). Before the development of the SM, many particles had been discovered, but had not yet been codified into a complete framework. The Standard Model provided a unified theoretical framework which explained observed phenomena very well. Furthermore, it made many experimental predictions, such as the existence of the Higgs boson, and the confirmation of many of these has made the SM one of the most well-supported theories developed in the last century. Figure 1. A table showing the particles in the standard model of particle physics. [7] Broadly, the SM organizes subatomic particles into 3 major categories: quarks, leptons, and gauge bosons. Quarks are spin-½ particles which make up most of the mass of visible matter in the universe; nucleons (protons and neutrons) are composed of quarks. -

Beyond the Standard Model Physics at CLIC

RM3-TH/19-2 Beyond the Standard Model physics at CLIC Roberto Franceschini Università degli Studi Roma Tre and INFN Roma Tre, Via della Vasca Navale 84, I-00146 Roma, ITALY Abstract A summary of the recent results from CERN Yellow Report on the CLIC potential for new physics is presented, with emphasis on the di- rect search for new physics scenarios motivated by the open issues of the Standard Model. arXiv:1902.10125v1 [hep-ph] 25 Feb 2019 Talk presented at the International Workshop on Future Linear Colliders (LCWS2018), Arlington, Texas, 22-26 October 2018. C18-10-22. 1 Introduction The Compact Linear Collider (CLIC) [1,2,3,4] is a proposed future linear e+e− collider based on a novel two-beam accelerator scheme [5], which in recent years has reached several milestones and established the feasibility of accelerating structures necessary for a new large scale accelerator facility (see e.g. [6]). The project is foreseen to be carried out in stages which aim at precision studies of Standard Model particles such as the Higgs boson and the top quark and allow the exploration of new physics at the high energy frontier. The detailed staging of the project is presented in Ref. [7,8], where plans for the target luminosities at each energy are outlined. These targets can be adjusted easily in case of discoveries at the Large Hadron Collider or at earlier CLIC stages. In fact the collision energy, up to 3 TeV, can be set by a suitable choice of the length of the accelerator and the duration of the data taking can also be adjusted to follow hints that the LHC may provide in the years to come. -

Baryon and Lepton Number Anomalies in the Standard Model

Appendix A Baryon and Lepton Number Anomalies in the Standard Model A.1 Baryon Number Anomalies The introduction of a gauged baryon number leads to the inclusion of quantum anomalies in the theory, refer to Fig. 1.2. The anomalies, for the baryonic current, are given by the following, 2 For SU(3) U(1)B , ⎛ ⎞ 3 A (SU(3)2U(1) ) = Tr[λaλb B]=3 × ⎝ B − B ⎠ = 0. (A.1) 1 B 2 i i lef t right 2 For SU(2) U(1)B , 3 × 3 3 A (SU(2)2U(1) ) = Tr[τ aτ b B]= B = . (A.2) 2 B 2 Q 2 ( )2 ( ) For U 1 Y U 1 B , 3 A (U(1)2 U(1) ) = Tr[YYB]=3 × 3(2Y 2 B − Y 2 B − Y 2 B ) =− . (A.3) 3 Y B Q Q u u d d 2 ( )2 ( ) For U 1 BU 1 Y , A ( ( )2 ( ) ) = [ ]= × ( 2 − 2 − 2 ) = . 4 U 1 BU 1 Y Tr BBY 3 3 2BQYQ Bu Yu Bd Yd 0 (A.4) ( )3 For U 1 B , A ( ( )3 ) = [ ]= × ( 3 − 3 − 3) = . 5 U 1 B Tr BBB 3 3 2BQ Bu Bd 0 (A.5) © Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018 133 N. D. Barrie, Cosmological Implications of Quantum Anomalies, Springer Theses, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94715-0 134 Appendix A: Baryon and Lepton Number Anomalies in the Standard Model 2 Fig. A.1 1-Loop corrections to a SU(2) U(1)B , where the loop contains only left-handed quarks, ( )2 ( ) and b U 1 Y U 1 B where the loop contains only quarks For U(1)B , A6(U(1)B ) = Tr[B]=3 × 3(2BQ − Bu − Bd ) = 0, (A.6) where the factor of 3 × 3 is a result of there being three generations of quarks and three colours for each quark.