How the Great Migration Changed the Face of the Democratic Party

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race, Governmentality, and the De-Colonial Politics of the Original Rainbow Coalition of Chicago

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2012-01-01 In The pirS it Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago Antonio R. Lopez University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Lopez, Antonio R., "In The pS irit Of Liberation: Race, Governmentality, And The e-CD olonial Politics Of The Original Rainbow Coalition Of Chicago" (2012). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 2127. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/2127 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERNMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO ANTONIO R. LOPEZ Department of History APPROVED: Yolanda Chávez-Leyva, Ph.D., Chair Ernesto Chávez, Ph.D. Maceo Dailey, Ph.D. John Márquez, Ph.D. Benjamin C. Flores, Ph.D. Interim Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Antonio R. López 2012 IN THE SPIRIT OF LIBERATION: RACE, GOVERMENTALITY, AND THE DE-COLONIAL POLITICS OF THE ORIGINAL RAINBOW COALITION OF CHICAGO by ANTONIO R. LOPEZ, B.A., M.A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO August 2012 Acknowledgements As with all accomplishments that require great expenditures of time, labor, and resources, the completion of this dissertation was assisted by many individuals and institutions. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Afro-Caribbeans and the New Great Migration to Atlanta

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 On the Midnight Train to Georgia: Afro-Caribbeans and the New Great Migration to Atlanta LaToya Asantelle Tavernier Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/630 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ON THE MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGIA: AFRO-CARIBBEANS AND THE NEW GREAT MIGRATION TO ATLANTA by LATOYA A. TAVERNIER A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2015 © 2015 LATOYA A. TAVERNIER All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Vilna Bashi Treitler Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Philip Kasinitz Date Executive Officer Prof. Philip Kasinitz Prof. Nancy Foner Prof. Charles Green Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract ON THE MIDNIGHT TRAIN TO GEORGIA: AFRO-CARIBBEANS AND THE NEW GREAT MIGRATION TO ATLANTA by LaToya A. Tavernier Advisor: Vilna Bashi Treitler In the 21 st century, Atlanta, Georgia has become a major new immigrant destination. This study focuses on the migration of Afro-Caribbeans to Atlanta and uses data collected from in-depth interviews, ethnography, and the US Census to understand: 1) the factors that have contributed to the emergence of Atlanta as a new destination for Afro-Caribbean immigrants and 2) the ways in which Atlanta’s large African American population, and its growing immigrant population, shape the incorporation of Afro-Caribbeans, as black immigrants, into the southern city. -

Loving Cities Index 5

Creating Loving Systems Across Communities to Provide All Students an Opportunity to Thrive JULY 2020 www.lovingcities.org TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE FROM SCHOTT PRESIDENT & CEO 1 FOREWORD FROM NIKOLE HANNAH-JONES 3 ABOUT THE LOVING CITIES INDEX 5 OVERVIEW OF ACCESS TO SUPPORTS 7 ALBUQUERQUE, NM 10 ALTANTA, GA 17 DALLAS, TX 24 DETROIT, MI 32 HARTFORD, CT 39 JACKSON, MS 46 MIAMI, FL 53 OAKLAND, CA 60 PROVIDENCE, RI 67 ST. PAUL, MN 74 HOW YOU CAN JOIN THE MOVEMENT TO CREATE LOVING SYSTEMS 82 APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY 88 REFERENCES 97 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Schott Foundation is grateful to our grassroots grantees and the remarkable leaders who fight for racial justice and educational equity each and every day. Their organizing and collaboration are the engine driving to create more loving communities. Schott is fortunate to have many philanthropic partners in our work. We are particularly indebted to six funders for their support of the Loving Cities Index project: Bertis Downs, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Nellie Mae Education Foundation, Schott Fund, Southern Education Foundation, and the Stuart Foundation. IMPAQ International conducted the qualitative and qualitative data collection in this second round of research, and worked with Schott to refine the framework and scoring rubric. Their team included Karen Armstrong, Ilana Barach, Mason Miller, and Kathryn Wiley. Patrick St. John designed the report, tackling the challenge of making the extensive data visually accessible. Finally, our deepest thanks to Allison Brown with Shepherd Impact Consulting who wrote this report and guided the project through every turn. LOVING CITIES INDEX Photo by Joe Piette PREFACE Leaning into the Arc Dr. -

Download Legal Document

Case 15-2398, Document 89, 11/19/2015, 1646899, Page1 of 45 15-2398 In The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit __________ BEVERLY ADKINS, CHARMAINE WILLIAMS, REBECCA PETTWAY, RUBBIE McCOY, WILLIAM YOUNG, on behalf of themselves and all others similarly situated, and MICHIGAN LEGAL SERVICES, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. MORGAN STANLEY, MORGAN STANLEY & CO. LLC, MORGAN STANLEY ABS CAPITAL I INC., MORGAN STANLEY MORTGAGE CAPITAL INC., and MORGAN STANLEY MORTGAGE CAPITAL HOLDINGS LLC, Defendants-Appellees. On Appeal from an Opinion and Order of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, Case No. 1:12-cv-7667-VEC-GWG __________________________________________________________________ BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL RACIAL JUSTICE PROJECT, THE DAMON J. KEITH CENTER FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, AND THE MICHIGAN WELFARE RIGHTS ORGANIZATION IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS __________________________________________________________________ JIN HEE LEE DEBORAH N. ARCHER DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF LITIGATION PROFESSOR OF LAW NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE & DIRECTOR, RACIAL JUSTICE PROJECT EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL 40 RECTOR STREET, 5TH FLOOR 185 WEST BROADWAY NEW YORK, NY 10006 NEW YORK, NY 10013 (212) 965-2200 (212) 431-2138 COUNSEL OF RECORD FOR AMICI CURIAE Case 15-2398, Document 89, 11/19/2015, 1646899, Page2 of 45 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Pursuant to Rule 26.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, amicus curiae files the following statement of disclosure: The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) corporation. It is not a publicly held corporation that issues stock, nor does it have any parent companies, subsidiaries or affiliates that have issued shares to the public. -

The Employment and Economic Advancement of African-Americans

Maurer School of Law: Indiana University Digital Repository @ Maurer Law Articles by Maurer Faculty Faculty Scholarship 2013 The Employment and Economic Advancement of African- Americans in the Twentieth Century Kenneth G. Dau-Schmidt Indiana University Maurer School of Law, [email protected] Ryland Sherman Indiana University - Bloomington Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Dau-Schmidt, Kenneth G. and Sherman, Ryland, "The Employment and Economic Advancement of African- Americans in the Twentieth Century" (2013). Articles by Maurer Faculty. 1292. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/1292 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by Maurer Faculty by an authorized administrator of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EMPLOYMENT AND ECONOMIC ADVANCEMENT OF AFRICAN–AMERICANS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Kenneth Glenn Dau-Schmidt and Ryland Sherman* In this article we examine the progress of African–Americans in the American labour market over the course of the twentieth century. We trace their progress as African-Americans moved from low-skill low- wage jobs in southern agriculture to a panoply of jobs including high- skill, high-wage jobs in industries and occupations across the country. We also document the migrations and improvements in educational achievement that have made this progress possible. We examine the progress yet to be made and especially the problems of lack of educa- tion and incarceration suffered by African–American males. -

Democratisation's Third Wave and the Challenges of Democratic Deepening

Good Governance, Aid Modalities and Poverty Reduction: Linkages to the Millennium Development Goals and Implications for Irish Aid Research project (RP-05-GG) of the Advisory Board for Irish Aid Working Paper 1 Democratisation’s Third Wave and the Challenges of Democratic Deepening: Assessing International Democracy Assistance and Lessons Learned Lise Rakner (Chr. Michelsen Institute), Alina Rocha Menocal (ODI) and Verena Fritz (ODI) August 2007 Disclaimer and acknowledgements The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Advisory Board for Irish Aid or those of any of the organisations in the research consortium implementing the project. The authors thank Bill Morton of the North-South Institute for comments on a previous draft, and Tammie O’Neil and Jo Adcock (ODI) for excellent editorial assistance. Responsibility for the content of published version remains with the authors. Overseas Development Institute 111 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7JD, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7922 0300 Fax: +44 (0)20 7922 0399 www.odi.org.uk ii Contents Executive summary ...........................................................................................................v 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.1 The emergence of democracy assistance............................................................................... 1 1.2 Democracy assistance and the broader ‘good governance’ agenda ..................................... -

Rethinking Work and Citizenship Jennifer Gordon Fordham University School of Law, [email protected]

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2007 Rethinking Work and Citizenship Jennifer Gordon Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Robin A. Lenhardt Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation 55 UCLA L. Rev. 1161 (2007-2008) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETHINKING WORK AND CITIZENSHIP Jennifer Gordon R.A. Lenhardt This Article advances a new approach to understanding the relationship between work and citizenship that comes out of research on African American and Latino immigrant low-wage workers. Media accounts typically portray African Americans and Latino immigrants as engaged in a pitched battle for jobs. Conventional wisdom suggests that the source of tension between these groups is labor competition or the racial prejudice of employers. While these expla- nations offer useful insights, they do not fully explain the intensity and longevity of the conflict. Nor has relevant legal scholarship offered a sufficient theoretical lens through which this conflict can be viewed. In the absence of such a theory, opportunities for solidarity building are lost and normative solutions in the context of immigration and antidiscriminationlaw reform are unsatisfying. -

Volume 19.1 National Political Science Review Caribbeanization of Black Politics May 16 2018

NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 Yvette Clarke U.S. Representative (D.-MA) CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW VOLUME 19.1 CARIBBEANIZATION OF BLACK POLITICS SHARON D. WRIGHT AUSTIN, GUEST EDITOR A PUBLICATION OF THE NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF BLACK POLITICAL SCIENTISTS THE NATIONAL POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW EDITORS Managing Editor Tiffany Willoughby-Herard University of California, Irvine Associate Managing Editor Julia Jordan-Zachery Providence College Duchess Harris Macalester College Sharon D. Wright Austin The University of Florida Angela K. Lewis University of Alabama, Birmingham BOOK REVIEW EDITOR Brandy Thomas Wells Augusta University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Melina Abdullah—California State University, Los Angeles Keisha Lindsey—University of Wisconsin Anthony Affigne—Providence College Clarence Lusane—American University Nikol Alexander-Floyd—Rutgers University Maruice Mangum—Alabama State University Russell Benjamin—Northeastern Illinois University Lorenzo Morris—Howard University Nadia Brown—Purdue University Richard T. Middleton IV—University of Missouri, St. Louis Niambi Carter—Howard University Byron D’Andra Orey—Jackson State University Cathy Cohen—University of Chicago Marion Brown—Brown University Dewey Clayton—University of Louisville Dianne Pinderhughes—University of Notre Dame Nyron Crawford—Temple University Matt Platt—Morehouse College Heath Fogg-Davis—Temple University H.L.T. Quan—Arizona State University Pearl Ford Dowe—University of Arkansas Boris Ricks—California State University, Northridge Kamille Gentles Peart—Roger Williams University Christina Rivers—DePaul University Daniel Gillion—University of Pennsylvania Neil Roberts—Williams College Ricky Green—California State University, Sacramento Fatemeh Shafiei—Spelman College Jean-Germain Gros—University of Missouri, St. -

Democratisation's Third Wave and the Challenges of Democratic Deepening

Good Governance, Aid Modalities and Poverty Reduction: Linkages to the Millennium Development Goals and Implications for Irish Aid Research project (RP-05-GG) of the Advisory Board for Irish Aid Working Paper 1 Democratisation’s Third Wave and the Challenges of Democratic Deepening: Assessing International Democracy Assistance and Lessons Learned Lise Rakner (Chr. Michelsen Institute), Alina Rocha Menocal (ODI) and Verena Fritz (ODI) August 2007 Disclaimer and acknowledgements The views presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Advisory Board for Irish Aid or those of any of the organisations in the research consortium implementing the project. The authors thank Bill Morton of the North-South Institute for comments on a previous draft, and Tammie O’Neil and Jo Adcock (ODI) for excellent editorial assistance. Responsibility for the content of published version remains with the authors. Overseas Development Institute 111 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7JD, UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7922 0300 Fax: +44 (0)20 7922 0399 www.odi.org.uk ii Contents Executive summary ...........................................................................................................v 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.1 The emergence of democracy assistance............................................................................... 1 1.2 Democracy assistance and the broader ‘good governance’ agenda ..................................... -

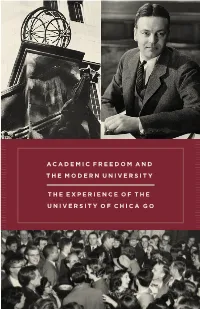

Academic Freedom and the Modern University

— — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And — — — — — — the modern University — — — — — — — — the experience oF the — — — — — — University oF chicA go — — — — — — — — — AcAdemic Freedom And the modern University the experience oF the University oF chicA go by john w. boyer 1 academic freedom introdUction his little book on academic freedom at the University of Chicago first appeared fourteen years ago, during a unique moment in our University’s history.1 Given the fundamental importance of freedom of speech to the scholarly mission T of American colleges and universities, I have decided to reissue the book for a new generation of students in the College, as well as for our alumni and parents. I hope it produces a deeper understanding of the challenges that the faculty of the University confronted over many decades in establishing Chicago’s national reputation as a particu- larly steadfast defender of the principle of academic freedom. Broadly understood, academic freedom is a principle that requires us to defend autonomy of thought and expression in our community, manifest in the rights of our students and faculty to speak, write, and teach freely. It is the foundation of the University’s mission to discover, improve, and disseminate knowledge. We do this by raising ideas in a climate of free and rigorous debate, where those ideas will be challenged and refined or discarded, but never stifled or intimidated from expres- sion in the first place. This principle has met regular challenges in our history from forces that have sought to influence our curriculum and research agendas in the name of security, political interests, or financial 1. John W. -

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019

Codebook: Government Composition, 1960-2019 Codebook: SUPPLEMENT TO THE COMPARATIVE POLITICAL DATA SET – GOVERNMENT COMPOSITION 1960-2019 Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann The Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set provides detailed information on party composition, reshuffles, duration, reason for termination and on the type of government for 36 democratic OECD and/or EU-member countries. The data begins in 1959 for the 23 countries formerly included in the CPDS I, respectively, in 1966 for Malta, in 1976 for Cyprus, in 1990 for Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia, in 1991 for Poland, in 1992 for Estonia and Lithuania, in 1993 for Latvia and Slovenia and in 2000 for Croatia. In order to obtain information on both the change of ideological composition and the following gap between the new an old cabinet, the supplement contains alternative data for the year 1959. The government variables in the main Comparative Political Data Set are based upon the data presented in this supplement. When using data from this data set, please quote both the data set and, where appropriate, the original source. Please quote this data set as: Klaus Armingeon, Sarah Engler and Lucas Leemann. 2021. Supplement to the Comparative Political Data Set – Government Composition 1960-2019. Zurich: Institute of Political Science, University of Zurich. These (former) assistants have made major contributions to the dataset, without which CPDS would not exist. In chronological and descending order: Angela Odermatt, Virginia Wenger, Fiona Wiedemeier, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, Sarah Engler, David Weisstanner, Panajotis Potolidis, Marlène Gerber, Philipp Leimgruber, Michelle Beyeler, and Sarah Menegal.