Kannada Versus Sanskrit: Hegemony, Power and Subjugation Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faculty Profile

FACULTY PROFILE * NAME . : DR. PARASHURAM. G. MALAGE MA. Ph.D. SLET. B.Ed. Dip.in Ambedkar studies * DESIGNATION : ASSISTANT PROFESSOR * ADDRESS : H.O.D. of HINDI and ASSISTANT PROFESSOR BESANT WOMEN'S COLLEGE, KODIALBAIL MANGALORE -575003 * CELL.NO : 8277156735 / 9008371806 * EMAIL : [email protected] * EDUCATIONAL QULIFICATION : DEGREE INSTITUTION YEAR UG - BA KarnatakaUniversityDharawad 1998 PG - MA ” 2000 Ph.D ” 2006 SLET Govt.of Karnataka 2000 B.Ed Karnataka University Darawad 2009 * CAREER PROFILE : * Presently working with Department of Hindi, Besant Women's College, and Mangalore. * TEACHING EXPERIENCE : 15 Year's. 12 YEAR'S in UG colleges. 04 YEAR'S in PG (Karnataka university Dharawad and kuvempu university Shivamogga ). * SUBJECT TAUGHT : HINDI * MEMBER OF BORDS : 1.Member of the Board of Examination in MA (Hindi – PG) during 2016 . 2. Member of Advisory Committee, PG Dept.of Hindi Mangalore University. * PUBLICATION PROFILE : Under Publication 1) Study material for MA (Final year) and BA (final year. Opt.Hindi) (DDE - Kuvempu Univ ersity Shankarghatta - Shivamogga). 2) Study material for MA (final year ) - (Karnataka State Open University - Mysor ). 3) Study material for MA ( First year ) (DDE- Mangaluru University, Mangaluru ) *Research Paper : Research paper published in book - Bharatiy bhashaon mein Ramnath(Kannada bhasha) ISBN no -978-93-5229-053-6 , Title -"Ramkath par adharit 'shudra tapasvi' Kavya natak. * AREA OF INTEREST : Hindi Literature and Linguistic. * ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT : 1. Participated in National Seminar, Jointly organize by Bharathiy Hindi Prishad, Allahabad and Dept. of Hindi K U Dharawad. 2. Participated in Two days National Seminar Organized by Dakshin Bharath Hindi Prachar Sabha Madras,Dharawad Branch. 3. Participated and Presented the Paper entitle " Mahadevi Varma ke kavya me Vedhana bhav" in One day National Seminar on Literature of Mahadevi varma, organized by Dept. -

The Mahatma As Proof: the Nationalist Origins of The

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Mahatma Misunderstood: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/77d6z8xw Author Shingavi, Snehal Ashok Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Mahatma Misunderstood: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism by Snehal Ashok Shingavi B.A. (Trinity University) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Prof. Abdul JanMohamed, chair Prof. Gautam Premnath Prof. Vasudha Dalmia Fall 2009 For my parents and my brother i Table of contents Chapter Page Acknowledgments iii Introduction: Misunderstanding the Mahatma: the politics and forms of South Asian literary nationalism 1 Chapter 1: The Mahatma as Proof: the nationalist origins of the historiography of Indian writing in English 22 Chapter 2: “The Mahatma didn’t say so, but …”: Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable and the sympathies of middle-class 53 nationalists Chapter 3: “The Mahatma may be all wrong about politics, but …”: Raja Rao’s Kanthapura and the religious imagination of the Indian, secular, nationalist middle class 106 Chapter 4: The Missing Mahatma: Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi and the genres and politics of Muslim anticolonialism 210 Conclusion: Nationalism and Internationalism 306 Bibliography 313 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, this dissertation would have been impossible without the support of my parents, Ashok and Ujwal, and my brother, Preetam, who had the patience to suffer through an unnecessarily long detour in my life. -

Social Transformation of Pakistan Under Urdu Language

Social Transformations in Contemporary Society, 2021 (9) ISSN 2345-0126 (online) SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION OF PAKISTAN UNDER URDU LANGUAGE Dr. Sohaib Mukhtar Bahria University, Pakistan [email protected] Abstract Urdu is the national language of Pakistan under article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. Urdu language is the first brick upon which whole building of Pakistan is built. In pronunciation both Hindi in India and Urdu in Pakistan are same but in script Indian choose their religious writing style Sanskrit also called Devanagari as Muslims of Pakistan choose Arabic script for writing Urdu language. Urdu language is based on two nation theory which is the basis of the creation of Pakistan. There are two nations in Indian Sub-continent (i) Hindu, and (ii) Muslims therefore Muslims of Indian sub- continent chanted for separate Muslim Land Pakistan in Indian sub-continent thus struggled for achieving separate homeland Pakistan where Muslims can freely practice their religious duties which is not possible in a country where non-Muslims are in majority thus Urdu which is derived from Arabic, Persian, and Turkish declared the national language of Pakistan as official language is still English thus steps are required to be taken at Government level to make Urdu as official language of Pakistan. There are various local languages of Pakistan mainly: Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto, Balochi, Kashmiri, Balti and it is fundamental right of all citizens of Pakistan under article 28 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973 to protect, preserve, and promote their local languages and local culture but the national language of Pakistan is Urdu according to article 251 of the Constitution of Pakistan 1973. -

Sanskrit Alphabet

Sounds Sanskrit Alphabet with sounds with other letters: eg's: Vowels: a* aa kaa short and long ◌ к I ii ◌ ◌ к kii u uu ◌ ◌ к kuu r also shows as a small backwards hook ri* rri* on top when it preceeds a letter (rpa) and a ◌ ◌ down/left bar when comes after (kra) lri lree ◌ ◌ к klri e ai ◌ ◌ к ke o au* ◌ ◌ к kau am: ah ◌ं ◌ः कः kah Consonants: к ka х kha ga gha na Ê ca cha ja jha* na ta tha Ú da dha na* ta tha Ú da dha na pa pha º ba bha ma Semivowels: ya ra la* va Sibilants: sa ш sa sa ha ksa** (**Compound Consonant. See next page) *Modern/ Hindi Versions a Other ऋ r ॠ rr La, Laa (retro) औ au aum (stylized) ◌ silences the vowel, eg: к kam झ jha Numero: ण na (retro) १ ५ ॰ la 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 @ Davidya.ca Page 1 Sounds Numero: 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 910 १॰ ॰ १ २ ३ ४ ६ ७ varient: ५ ८ (shoonya eka- dva- tri- catúr- pancha- sás- saptán- astá- návan- dásan- = empty) works like our Arabic numbers @ Davidya.ca Compound Consanants: When 2 or more consonants are together, they blend into a compound letter. The 12 most common: jna/ tra ttagya dya ddhya ksa kta kra hma hna hva examples: for a whole chart, see: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/devanagari_conjuncts.php that page includes a download link but note the site uses the modern form Page 2 Alphabet Devanagari Alphabet : к х Ê Ú Ú º ш @ Davidya.ca Page 3 Pronounce Vowels T pronounce Consonants pronounce Semivowels pronounce 1 a g Another 17 к ka v Kit 42 ya p Yoga 2 aa g fAther 18 х kha v blocKHead -

Morphological Integration of Urdu Loan Words in Pakistani English

English Language Teaching; Vol. 13, No. 5; 2020 ISSN 1916-4742 E-ISSN 1916-4750 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Morphological Integration of Urdu Loan Words in Pakistani English Tania Ali Khan1 1Minhaj University/Department of English Language & Literature Lahore, Pakistan Correspondence: Tania Ali Khan, Minhaj University/Department of English Language & Literature Lahore, Pakistan Received: March 19, 2020 Accepted: April 18, 2020 Online Published: April 21, 2020 doi: 10.5539/elt.v13n5p49 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n5p49 Abstract Pakistani English is a variety of English language concerning Sentence structure, Morphology, Phonology, Spelling, and Vocabulary. The one semantic element, which makes the investigation of Pakistani English additionally fascinating is the Vocabulary. Pakistani English uses many loan words from Urdu language and other local dialects, which have become an integral part of Pakistani English, and the speakers don't feel odd while using these words. Numerous studies are conducted on Pakistani English Vocabulary, yet a couple manage to deal with morphology. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the morphological integration of Urdu loan words in Pakistani English. Another purpose of the study is to investigate the main reasons of this morphological integration process. The Qualitative research method is used in this study. Researcher prepares a sample list of 50 loan words for the analysis. These words are randomly chosen from the newspaper “The Dawn” since it is the most dispersed English language newspaper in Pakistan. Some words are selected from the Books and Novellas of Pakistani English fiction authors, and concise Oxford English Dictionary, 11th edition. -

Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-03-06 Document version: 2.6 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1. General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Kannada LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document: proposal-kannada-lgr-06mar19-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document: kannada-test-labels-06mar19-en.txt 2. Script for which the LGR is Proposed ISO 15924 Code: Knda ISO 15924 N°: 345 ISO 15924 English Name: Kannada Latin transliteration of the native script name: Native name of the script: ಕನ#ಡ Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-4 Some languages using the script and their ISO 639-3 codes: Kannada (kan), Tulu (tcy), Beary, Konkani (kok), Havyaka, Kodava (kfa) 1 Proposal for a Kannada Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) 3. Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It 3.1 Kannada language Kannada is one of the scheduled languages of India. It is spoken predominantly by the people of Karnataka State of India. It is one of the major languages among the Dravidian languages. Kannada is also spoken by significant linguistic minorities in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Kerala, Goa and abroad. -

Exploring Language Similarities with Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

EXPLORING LANGUAGE SIMILARITIES WITH DIMENSIONALITY REDUCTION TECHNIQUES Sangarshanan Veeraraghavan Final Year Undergraduate VIT Vellore [email protected] Abstract In recent years several novel models were developed to process natural language, development of accurate language translation systems have helped us overcome geographical barriers and communicate ideas effectively. These models are developed mostly for a few languages that are widely used while other languages are ignored. Most of the languages that are spoken share lexical, syntactic and sematic similarity with several other languages and knowing this can help us leverage the existing model to build more specific and accurate models that can be used for other languages, so here I have explored the idea of representing several known popular languages in a lower dimension such that their similarities can be visualized using simple 2 dimensional plots. This can even help us understand newly discovered languages that may not share its vocabulary with any of the existing languages. 1. Introduction Language is a method of communication and ironically has long remained a communication barrier. Written representations of all languages look quite different but inherently share similarity between them. For example if we show a person with no knowledge of English alphabets a text in English and then in Spanish they might be oblivious to the similarity between them as they look like gibberish to them. There might also be several languages which may seem completely different to even experienced linguists but might share a subtle hidden similarity as they is a possibility that languages with no shared vocabulary might still have some similarity. -

An Augmented Translation Technique for Low Resource Language Pair: Sanskrit to Hindi Translation

An Augmented Translation Technique for low Resource Language pair: Sanskrit to Hindi translation RASHI KUMAR, Malaviya National Institute of Technology, India PIYUSH JHA, Malaviya National Institute of Technology, India VINEET SAHULA, Malaviya National Institute of Technology, India Neural Machine Translation (NMT) is an ongoing technique for Machine Translation (MT) using enormous artificial neural network. It has exhibited promising outcomes and has shown incredible potential in solving challenging machine translation exercises. One such exercise is the best approach to furnish great MT to language sets with a little preparing information. In this work, Zero Shot Translation (ZST) is inspected for a low resource language pair. By working on high resource language pairs for which benchmarks are available, namely Spanish to Portuguese, and training on data sets (Spanish-English and English-Portuguese) we prepare a state of proof for ZST system that gives appropriate results on the available data. Subsequently the same architecture is tested for Sanskrit to Hindi translation for which data is sparse, by training the model on English-Hindi and Sanskrit-English language pairs. In order to prepare and decipher with ZST system, we broaden the preparation and interpretation pipelines of NMT seq2seq model in tensorflow, incorporating ZST features. Dimensionality reduction ofword embedding is performed to reduce the memory usage for data storage and to achieve a faster training and translation cycles. In this work existing helpful technology has been utilized in an imaginative manner to execute our Natural Language Processing (NLP) issue of Sanskrit to Hindi translation. A Sanskrit-Hindi parallel corpus of 300 is constructed for testing. -

KUVEMPU UNIVERSITY Gnana Sahyadri Distt

KUVEMPU UNIVERSITY Gnana Sahyadri Distt. Shimoga - 577 451, Karnataka Phone: EPABX: 08282- 256301 to 256307 FAX : 08282: 256262, 256255 Email : [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],[email protected], Website : http://www.kuvempu.ac.in Vice Chancellor : Prof. T.R.Manjunath Registrar : Prof. Mallika S. Ghanti Kuvempu University is a young affiliating University in Karnataka. Established in 1987, it is a University with a distinctive academic profile, blending in itself commitment to rural ethos and a modern spirit. It has 41 Post-Graduate departments of studies in the faculties of Arts, Science, Commerce, Education and Law. Offering 45 Post-Graduate Programmes, 4 P.G.Diploma and one Under-Graduate programme. The University has 80 affiliated colleges, three con stituent colleges (among three, one is autonomous college) and other one autonomous college, one B.P.Ed. college, and 17 B.Ed. colleges under its jurisdiction spread over 2 districts of Shimoga, and Chikmagalur. It also has outlying regional Post-Graduate centre at Kadur. Jnana Sahyadri, the main campus of Kuvempu University is located at Shankaraghatta at a distance of 28 kms. from Shimoga town, the district headquarters and 18 kms. from Bhadravathi, the well-known industrial town. The campus is only 2 kms. from the magnificent Bhadra Reservoir across the river Bhadra, one of the important life lines of the area. The main buildings of the University have been constructed on a small hillock, thus blending naturally with the landscape. The campus sprawls over an area of 230 acres. The entire campus area is free from any form of pollution including noise pollution. -

English Third Language (REVISED) ©Ktbs10republished Tenthbe Standard To

Government of Karnataka English Third Language (REVISED) ©KTBS10republished Tenthbe Standard to Karnataka Textbook Society (R.) Not100 Feet Ring Road, Banashankari 3rd Stage, Bengaluru - 560 085 i Preface Textbook Society, Karnataka has been engaged in producing new textbooks according to the new syllabi which in turn are designed on NCF – 2005 since June 2010. Textbooks are prepared in 12 languages; seven of them serve as the media of instruction. From standard 1 to 4 there is the EVS, mathematics and 5th to 10th there are three core subjects namely mathematics, science and social science. NCF – 2005 has a number of special features and they are: connecting knowledge to life activities learning to shift from rote methods enriching the curriculum beyond textbooks learning experiences for the construction of knowledge making examinations flexible and integrating them with classroom experiences caring concerns within the democratic policy of the country making education relevant to the present and future needs. softening the subject boundaries- integrated knowledge and the joy of learning. the child is the constructor of knowledge The new©KTBS books are producedrepublished based on three fundamental approaches namely. Constructive approach, Spiral Approach and Integrated approach The learner is encouragedbe to think, engage in activities, master skills and competencies. The materials presented in these books are integrated with values. The new books are not examination oriented in their nature. On the other hand they help the learner in theto all round development of his/her personality, thus help him/her become a healthy member of a healthy society and a productive citizen of this great country, India. -

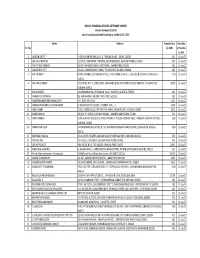

(In INR) Due Date of Transfer to IEPF 1 AAYUSH GUPTA C 118

ORACLE FINANCIAL SERVICES SOFTWARE LIMITED Interim Dividend 2019-20 List of unpaid/unclaimed Dividend as on March 31, 2021 Name Address Amount Due Due date Sr. No. (in INR) of transfer to IEPF 1 AAYUSH GUPTA C 118 MAHENDRU ENCLAVE, G T KARNAL ROAD, , DELHI, 110033 180 11-Jun-27 2 ABHILASH KONDAI 12/5/55/1 VIJAYAPURI, TARNAKA, SECUNDERABAD, ANDHRA PRADESH, 500017 900 11-Jun-27 3 ADITYA DEV PRAHLAD E/1316 IIM AHMEDABAD, VASTRAPUR, , AHMEDABAD, 380015 180 11-Jun-27 4 AMALENDU SETH 84 A/1C, CHANDI GHOSH ROAD, TOLLYGUNGE, KOLKATA 700040 180 11-Jun-27 5 AMIT KUMAR ROOM NUMBER-227,SHISHIR HOSTEL,, PUSA CAMPUS I.A.R.I,I., NEW DELHI CENTRAL, NEW DELHI, 720 11-Jun-27 110012 6 AMIT M CHORDIA 273, OFFICE NO.- 3, 2ND FLOOR, ARADHANA BLDG, NR CENTRAL PLAZA THEATRE, OPERAHOUSE, 4,995 11-Jun-27 MUMBAI 400004 7 AMLAN DATTA 116 KALIKAPUR RD, VIVEKANDA PALLY, KOLKATA, KOLKATA, 700078 180 11-Jun-27 8 ANANDATHEERTHAN H 68, AGRAHARAM, MUSIRI, TRICHY DIST, 621211 180 11-Jun-27 9 ANANTHRAMAN KRISHNAMOORTHY P.O . BOX. 875, DOHA 1,426 11-Jun-27 10 ANEKAL BASAVARAJU SATISHKUMAR 4, INVERNESS DR, EDISON,, NJ 08820. USA, , , 0 3,564 11-Jun-27 11 ANIL MISHRA D 5/51 GREEN FIELDS, OPP FANTASY LAND, ANDHERI EAST, MUMBAI, 400093 3,600 11-Jun-27 12 ANILKUMAR K P 1851/A, 7th CROSS, SUBHASH NAGAR, , MANDYA KARNATAKA, 571401 540 11-Jun-27 13 ANITA PAREKH NEAR SHRIRAM SCHOOL 12 PEARL PRABHA, V P ROAD ANDHERI WEST, ANDHERI RAILWAY STATION, 900 11-Jun-27 MUMBAI, 400058 14 ANITHA MATHEW KAYYALACKAKOM FLAT NO 3F, DD SAMUDRADARSHAN, MARINE DRIVE, ERNAKULAM, KERALA, 900 11-Jun-27 -

Kannada Literature Syllabus

Kannada Literature Syllabus UPSC Civil Services Mains Exam is of Optional Subject and consists of 2 papers. Each paper is of 250 marks with a total of 500 marks. KANNADA PAPER-I (Answers must be written in Kannada) Section-A History of Kannada Language What is Language? General charecteristics of Language. Dravidian Family of Languages and its specific features, Antiquity of Kannada Language, Different Phases of its Development. Dialects of Kannada Language : Regional and Social Various aspects of development of Kannada Language : phonological and Semantic changes. Language borrowing. History of Kannada Literature Ancient Kannada literature : Influence and Trends. Poets for study : Specified poets from Pampa to Ratnakara Varni are to be studied in the light of contents, form and expression : Pampa, Janna, Nagachandra. Medieval Kannada literature : Influence and Trends. Vachana literature : Basavanna, Akka Mahadevi. Medieval Poets : Harihara, Ragha-vanka, Kumar-Vyasa. Dasa literature : Purandra and Kanaka. Sangataya : Ratnakaravarni Modern Kannada literature : Influence, trends and idealogies, Navodaya, Pragatishila, Navya, Dalita and Bandaya. Section-B Poetics and literary criticism : Definition and concepts of poetry : Word, Meaning, Alankara, Reeti, Rasa, Dhwani, Auchitya. Interpretations of Rasa Sutra. Modern Trends of literary criticism : Formalist, Historical, Marxist, Feminist, Post-colonial criticism. Cultural History of Karnataka Contribution of Dynasties to the culture of Karnataka : Chalukyas of Badami and Kalyani, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, Vijayanagara rulers, in literary context. Major religions of Karnataka and their cultural contributions. Arts of Karnataka : Sculpture, Architecture, Painting, Music, Dance-in the literary context. Unification of Karnataka and its impact on Kannada literature. PAPER-II (Answers must be written in Kannada) The paper will require first-hand reading of the Texts prescribed and will be designed to test the critical ability of the candidates.