Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linguistics for the Use of African History and the Comparative Study of Bantu Pottery Vocabulary

LINGUISTICS FOR THE USE OF AFRICAN HISTORY AND THE COMPARATIVE STUDY OF BANTU POTTERY VOCABULARY Koen Bostoen Université Libre de Bruxelles1 Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren 1. Introduction Ever since African historical linguistics emerged in the 19th century, it has served a double purpose. It has not only been practiced with the aim of studying language evolution, its methods have also been put to use for the reconstruction of human history. The promotion of linguistics to one of the key disciplines of African historiography is an inevitable consequence of the lack of ancient written records in sub-Saharan Africa. Scholars of the African past generally fall back on two kinds of linguistic research: linguistic classifi- cation and linguistic reconstruction. The aim of this paper is to present a con- cise application of both disciplines to the field of Bantu linguistics and to offer two interesting comparative case studies in the field of Bantu pottery vocabulary. The diachronic analysis of this lexical domain constitutes a promising field for interdisciplinary historical research. At the same time, the examples presented here urge history scholars to be cautious in the applica- tion of words-and-things studies for the use of historical reconstruction. The neglect of diachronic semantic evolutions and the impact of ancient lexical copies may lead to oversimplified and hence false historical conclusions. 2. Bantu languages and the synchronic nature of historical linguistics Exact estimations being complicated by the lack of good descriptive ma- terial, the Bantu languages are believed to number at present between 400 and 600. They are spoken in almost half of all sub-Saharan countries: Camer- 1 My acknowledgement goes to Yvonne Bastin, Claire Grégoire, Jacqueline Renard, Ellen Vandendorpe and Annemie Van Geldre who assisted me in the preparation of this paper. -

Wr:X3,Clti: Lilelir)

ti:_Lilelir) 1^ (Dr\ wr:x3,cL KONINKLIJK MUSEUM MUSEE ROYAL DE VOOR MIDDEN-AFRIKA L'AFRIQUE CENTRALE TERVUREN, BELGIË TERVUREN, BELGIQUE INVENTARIS VAN INVENTAIRE DES HET HISTORISCH ARCHIEF VOL. 8 ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES LA MÉMOIRE DES BELGES EN AFRIQUE CENTRALE INVENTAIRE DES ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES PRIVÉES DU MUSÉE ROYAL DE L'AFRIQUE CENTRALE DE 1858 À NOS JOURS par Patricia VAN SCHUYLENBERGH Sous la direction de Philippe MARECHAL 1997 Cet ouvrage a été réalisé dans le cadre du programme "Centres de services et réseaux de recherche" pour le compte de l'Etat belge, Services fédéraux des affaires scientifiques, techniques et culturelles (Services du Premier Ministre) ISBN 2-87398-006-0 D/1997/0254/07 Photos de couverture: Recto: Maurice CALMEYN, au 2ème campement en . face de Bima, du 28 juin au 12 juillet 1907. Verso: extrait de son journal de notes, 12 juin 1908. M.R.A.C., Hist., 62.31.1. © AFRICA-MUSEUM (Tervuren, Belgium) INTRODUCTION La réalisation d'un inventaire des papiers de l'Etat ou de la colonie, missionnaires, privés de la section Histoire de la Présence ingénieurs, botanistes, géologues, artistes, belge Outre-Mer s'inscrit dans touristes, etc. - de leur famille ou de leurs l'aboutissement du projet "Centres de descendants et qui illustrent de manière services et réseaux de recherche", financé par extrêmement variée, l'histoire de la présence les Services fédéraux des affaires belge - et européenne- en Afrique centrale. scientifiques, techniques et culturelles, visant Quelques autres centres de documentation à rassembler sur une banque de données comme les Archives Générales du Royaume, informatisée, des témoignages écrits sur la le Musée royal de l'Armée et d'Histoire présence belge dans le monde et a fortiori, en militaire, les congrégations religieuses ou, à Afrique centrale, destination privilégiée de la une moindre échelle, les Archives Africaines plupart des Belges qui partaient à l'étranger. -

The Kenyan British Colonial Experience

Peace and Conflict Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Decolonizing Through a Peace and Article 2 Conflict Studies Lens 5-2018 Modus Operandi of Oppressing the “Savages”: The Kenyan British Colonial Experience Peter Karari [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Karari, Peter (2018) "Modus Operandi of Oppressing the “Savages”: The Kenyan British Colonial Experience," Peace and Conflict Studies: Vol. 25 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.46743/1082-7307/2018.1436 Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs/vol25/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace & Conflict Studies at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace and Conflict Studies by an authorized editor of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modus Operandi of Oppressing the “Savages”: The Kenyan British Colonial Experience Abstract Colonialism can be traced back to the dawn of the “age of discovery” that was pioneered by the Portuguese and the Spanish empires in the 15th century. It was not until the 1870s that “New Imperialism” characterized by the ideology of European expansionism envisioned acquiring new territories overseas. The Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 prepared the ground for the direct rule and occupation of Africa by European powers. In 1895, Kenya became part of the British East Africa Protectorate. From 1920, the British colonized Kenya until her independence in 1963. As in many other former British colonies around the world, most conspicuous and appalling was the modus operandi that was employed to colonize the targeted territories. -

'Mau Mau' and Colonialism in Kenya

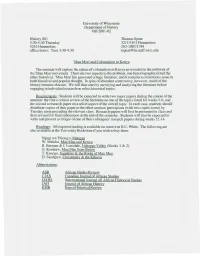

University of Wisconsin Department of History Fall2001-02 History 861 Thomas Spear 3:30-5:30 Thursday 3211/5101 Humanities 5245 Humanities 263-1807/1784 office hours: Tues 3:30-4:30 tspear@facstaff. wisc.edu 'Mau Mau' and Colonialism in Kenya The seminar will explore the nature of colonialism in Kenya as revealed in the outbreak of the 'Mau Mau' movement. There are two aspects to the problem: one historiographical and the other historical. 'Mau Mau' has generated a huge literature, and it remains a contentious issue in both historical and popular thought. In spite of abundant controversy, however, much of the history remains obscure. We will thus start by surveying and analyzing the literature before engaging in individual research on select historical topics. Requirements: Students will be expected to write two major papers during the course of the seminar: the first a critical review of the literature on one of the topics listed for weeks 2-9, and the second a research paper on a select aspect of the overall topic. In each case, students should distribute copies oftheir paper to the other seminar participants (with two copies to me) by Tuesday noon preceding the relevant class. Research papers will first be presented in class and then revised for final submission at the end of the semester. Students will also be expected to write and present a critique of one of their colleagues' research papers during weeks 12-14. Readings: All required reading is available on reserve at H. C. White. The following are also available at the University Bookstore if you wish to buy them: Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Matigari W. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

1646 KMS Kenya Past and Present Issue 46.Pdf

Kenya Past and Present ISSUE 46, 2019 CONTENTS KMS HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 3 Pat Jentz NMK HIGHLIGHTS, 2018 7 Juliana Jebet NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS 13 AT MT. ELGON CAVES, WESTERN KENYA Emmanuel K. Ndiema, Purity Kiura, Rahab Kinyanjui RAS SERANI: AN HISTORICAL COMPLEX 22 Hans-Martin Sommer COCKATOOS AND CROCODILES: 32 SEARCHING FOR WORDS OF AUSTRONESIAN ORIGIN IN SWAHILI Martin Walsh PURI, PAROTHA, PICKLES AND PAPADAM 41 Saryoo Shah ZANZIBAR PLATES: MAASTRICHT AND OTHER PLATES 45 ON THE EAST AFRICAN COAST Villoo Nowrojee and Pheroze Nowrojee EXCEPTIONAL OBJECTS FROM KENYA’S 53 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES Angela W. Kabiru FRONT COVER ‘They speak to us of warm welcomes and traditional hospitality, of large offerings of richly flavoured rice, of meat cooked in coconut milk, of sweets as generous in quantity as the meals they followed.’ See Villoo and Pheroze Nowrojee. ‘Zanzibar Plates’ p. 45 1 KMS COUNCIL 2018 - 2019 KENYA MUSEUM SOCIETY Officers The Kenya Museum Society (KMS) is a non-profit Chairperson Pat Jentz members’ organisation formed in 1971 to support Vice Chairperson Jill Ghai and promote the work of the National Museums of Honorary Secretary Dr Marla Stone Kenya (NMK). You are invited to join the Society and Honorary Treasurer Peter Brice receive Kenya Past and Present. Privileges to members include regular newsletters, free entrance to all Council Members national museums, prehistoric sites and monuments PR and Marketing Coordinator Kari Mutu under the jurisdiction of the National Museums of Weekend Outings Coordinator Narinder Heyer Kenya, entry to the Oloolua Nature Trail at half price Day Outings Coordinator Catalina Osorio and 5% discount on books in the KMS shop. -

Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center

A PR I L 2 0 1 0 Strengthening the humanity and dignity of people in crisis through knowledge and practice Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship Between Aid and Security in Kenya Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman ©2010 Feinstein International Center. All Rights Reserved. Fair use of this copyrighted material includes its use for non-commercial educational purposes, such as teaching, scholarship, research, criticism, commentary, and news reporting. Unless otherwise noted, those who wish to reproduce text and image files from this publication for such uses may do so without the Feinstein International Center’s express permission. However, all commercial use of this material and/or reproduction that alters its meaning or intent, without the express permission of the Feinstein International Center, is prohibited. Feinstein International Center Tufts University 200 Boston Ave., Suite 4800 Medford, MA 02155 USA tel: +1 617.627.3423 fax: +1 617.627.3428 fic.tufts.edu Acknowledgements The report has been written by Mark Bradbury and Michael Kleinman, who take responsibility for its contents and conclusions. We wish to thank our co-researchers Halima Shuria, Hussein A. Mahmoud, and Amina Soud for their substantive contribution to the research process. Andrew Catley, Lynn Carter, and Jan Bachmann provided insightful comments on a draft of the report. Dawn Stallard’s editorial skills made the report more readable. For reasons of confidentiality, the names of some individuals interviewed during the course of the research have been withheld. We wish to acknowledge and thank all of those who gave their time to be interviewed for the study. -

FBI054535 ~~N Diaspora Customs Traditions :··

ACLURM055018 FBI054535 US Somali Diaspora 8 Clan I0 Islamic Traditions II Flag . 12 Cultural Customs 16 Language ··13 .1ega[.Jssues .. :.... :"'. :·· .•... ;Appendix :,:·.\{ ... ~~N FBI054536 ACLURM055019 ~~ ~A~ History (U) 21 October. 1969: Corruption and a power vacuum in the Somali government Somalia, located at the Horn of Africa (U) culminate in a bloodless coup led by Major near the Arabian Peninsula, has been a General Muhammad Siad Barre. crossroads of civilization for thousands of years. Somalia played an important role in (U) 1969-1991: Siad Barre establishes the commerce of ancient Egyptians, and with a military dictatorship that divides and later Chinese, Greek, and Arab traders. oppresses Somalis. (U) 18th century: Somalis develop a (U) 27 January J99J: Siad Barre flees culture shaped by pastoral nomadism and Mogadishu, and the Somali state collapses~ adherence to Islam. Armed dan-based militias fight for power. (U) 1891-1960: European powers create (U) 1991-199S:The United Nations five separate Somali entities: Operation in Somalia (UNISOM) I and II- initially a US-led, UN-sanctioned multilateral » British Somaliland (north central). intervention-attempts to resolve the » French Somaliland (east and southeast). civil war and provide humanitarian aid. » Italian Somaliland (south). The ambitious UNISOM mandate to rebuild » Ethiopian Somaliland (the Ogaden). a Somali government threatens warlords' >> The Northern Frontier District (NFD) interests and fighting ensues. UN forces of Kenya. depart in 1995, leaving Somalia in a state (U) ., 960: Italian and British colonies of violence and anarchy. Nearly I million merge into the independent Somali Republic. refugees and almost 5 million people risk starvation and disease. Emigration rises (U} 1960-1969: Somalia remains sharply. -

Migrated Archives): Ceylon

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Ceylon Following earlier settlements by the Dutch and Despatches and registers of despatches sent to, and received from, the Colonial Portuguese, the British colony of Ceylon was Secretary established in 1802 but it was not until the annexation of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 that FCO 141/2180-2186, 2192-2245, 2248-2249, 2260, 2264-2273: the entire island came under British control. In Open, confidential and secret despatches covering a variety of topics including the acts and ordinances, 1948, Ceylon became a self-governing state and a the economy, agriculture and produce, lands and buildings, imports and exports, civil aviation, railways, member of the British Commonwealth, and in 1972 banks and prisons. Despatches regarding civil servants include memorials, pensions, recruitment, dismissals it became the independent republic under the name and suggestions for New Year’s honours. 1872-1948, with gaps. The years 1897-1903 and 1906 have been of Sri Lanka. release in previous tranches. Below is a selection of files grouped according to Telegrams and registers of telegrams sent to and received from the Colonial Secretary theme to assist research. This list should be used in conjunction with the full catalogue list as not all are FCO 141/2187-2191, 2246-2247, 2250-2263, 2274-2275 : included here. The files cover the period between Open, confidential and secret telegrams on topics such as imports and exports, defence costs and 1872 and 1948 and include a substantial number of regulations, taxation and the economy, the armed forces, railways, prisons and civil servants 1899-1948. -

A History of Nairobi, Capital of Kenya

....IJ .. Kenya Information Dept. Nairobi, Showing the Legislative Council Building TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Chapter I. Pre-colonial Background • • • • • • • • • • 4 II. The Nairobi Area. • • • • • • • • • • • • • 29 III. Nairobi from 1896-1919 •• • • • • • • • • • 50 IV. Interwar Nairobi: 1920-1939. • • • • • • • 74 V. War Time and Postwar Nairobi: 1940-1963 •• 110 VI. Independent Nairobi: 1964-1966 • • • • • • 144 Appendix • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 168 Bibliographical Note • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 179 Bibliography • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• 182 iii PREFACE Urbanization is the touchstone of civilization, the dividing mark between raw independence and refined inter dependence. In an urbanized world, countries are apt to be judged according to their degree of urbanization. A glance at the map shows that the under-developed countries are also, by and large, rural. Cities have long existed in Africa, of course. From the ancient trade and cultural centers of Carthage and Alexandria to the mediaeval sultanates of East Africa, urban life has long existed in some degree or another. Yet none of these cities changed significantly the rural character of the African hinterland. Today the city needs to be more than the occasional market place, the seat of political authority, and a haven for the literati. It remains these of course, but it is much more. It must be the industrial and economic wellspring of a large area, perhaps of a nation. The city has become the concomitant of industrialization and industrialization the concomitant 1 2 of the revolution of rising expectations. African cities today are largely the products of colonial enterprise but are equally the measure of their country's progress. The city is witness everywhere to the acute personal, familial, and social upheavals of society in the process of urbanization. -

Preface Chapter 1 Introduction

Notes PREFACE 1. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, p. 458. 2. In the First World War deaths of UK service personnel were 722 785, and civilians’ 1414. Whereas in the Second World War deaths of UK service personnel were (including merchant navy) 336 642 while civilian deaths were 60 284. Thorpe, Britain in the Era of the Two World Wars, pp. 49–50. 3. Cited in Fussell, Wartime, p. 131. 4. Fussell, Wartime, p. 140. 5. Malinowski, ‘A Plea for an Effective Colour Bar’, Spectator, 27 June 1931. CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Barkan, The Retreat of Scientific Racism, p. 1. 2. Malik, The Meaning of Race, p. 124. 3. Rich, Race and Empire in British Politics, p. 149. 4. ‘On 2 July 1949, for example, the Picture Post enquired “Is there a BRITISH COLOUR BAR?” and found to their evident surprise that indeed there was.’ CCCS, The Empire Strikes Back, pp. 68–9. 5. Condit and Lucaites, Crafting Equality, p. 173. 6. King, Separate and Unequal, p. 113. 7. Rex and Tomlinson, Colonial Immigrants in a British City, p. 38. 8. Lauren, Power and Prejudice, p. 35. 9. Rich, Race and Empire in British Politics, p. 149. 10. Condit and Lucaites, Crafting Equality, p. 171. 11. King, Separate and Unequal, p. 114. 12. Rose, The Negro in America, pp. 320–1. 13. ‘The intense phase of racial prejudice in the British Empire did not last very long. By the 1930s, as Dr. Perham has pointed out, the interest of the British in continuing to occupy the former German colonies caused them to emphasize the difference between their own racial attitudes and those of Hitler’s Germany.’ Symonds, The British and Their Successors, p. -

I Royal Engineers Journal

__ __________ T_ _I The ,i Royal Engineers Journal. The St. Lawrence Deep Waterway . Sir Alexander Gibb 216 i Movements of the Ground Level in Bengal . Colonel Sir Sidney Burrard 231 " | Notes on Tachymetric Traverses . Lieut. B. E. Bagnall-Wild 277 A Survey Party in Upper Burma Captain G. F.. He.aney 282 Elevated Reinforced-Concrete Reservoi . ajor C. C. S. White 290 a The Problem of Command in Combined Operations Bt. Lt.-Col. C. Dening 293 Progress Records for Major New Works . Major G. MacLeod Ross 311 Memoirs. Books. Magazines. Correspondence . 316 i VOL. XLVII. JUNE, 1933. CHATHAM: . V TIB INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINBBRS. TBLBPHONB: CHATHA, 2669. AGENTS AND PRINTERS: MACKAY LTD, LONDON: HIG, RBBl, LTD., 5, RRGENI STREET, S.W.I. ip 1iAU . L- to INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY DO NOT REMOVE i1 L1S . -....-. __--„.....: -.- - ,-- - . .- "EXPAMET" REINFORCED CONCRETE, Reinforcement for Concrete. PLASTER and " B B " Expanded Metal BRICK Lathing for Platerwork. Construction "RIBMET" WITH for Concrete and Plasterwork. "EXPAMET" EXPANDED METAL "EXMET" PRODUCTS Reinforcement for Brickwork. Mild Steel EX".MET Wall-ties. British Stel - British Labor. British Steel - British Labour. Write for illustrated technical literature. THE EXPANDED METAL COMPANY, LTD. Patentees and Manufacturers of Expanded Metal. Engineers for all forms of Reinforced Concrete and Fire-resistant Construction. Burwood House, Caxton Street, London, S.W.1. Works: West Hartlepool. Established over 40 years. IR Telephone: Woolwich 0275. 1, Artillery Place, Woolwich, S.E.18. Regent 3560. 6, St. James' Place, S.W.1. J. DANIELS & Co., Ltd., Military i Civilian Tailors, Outfitters and Breeches Makers. R.E. AND R.A.