Grabowski Hunt Critique

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lp Nazwisko Imię Adres Osoby Niepełnos Prawne 1 Abramiuk

Osoby niepełnos lp Nazwisko Imię Adres prawne 1 Abramiuk Maria Skłodowskiej 2 Bajda Stanisław Przewłoka 3 Bajda Wiesław Przewłoka N 4 Banach Zdzisława Jasionka 5 Banach Witold ul. 1 Maja 6 Bartnicka Monika Klonowa N 7 Bartoszek Henryk Parkowa N 8 Bloch Stefan Koczergi 9 Bodziak Zdzisław Koczergi 10 Borowicz Mariusz Polona N 11 Borowska Barbara Strażacka N 12 Borysiuk Małgorzata Szkolna 13 Bronikowski Marian ul. Kosmonautów 14 Burza Jolanta ul. PCK 15 Burzec Ewa Łąkowa 16 Bylicki Jan ul. Kościuszki 17 Bzówka Adam ul. Wiśniowa 18 Chilimoniuk Małgorzata ul. Szkolna 19 Chmielarz Bogumiła Miodowa 20 Chodacki Andrzej ul.Chałubińskiego 21 Chwalczuk Edward Jaworowa N 22 Chwalczuk Marek Laski 23 Chwedczuk Krystyna ul. Harcerska 24 Cieniuch Piotr ul. Partyzantów 25 Ciok Andrzej Wiśniowa N 26 Ciołek Józef Koczergi N 27 Ciopciński Marian ul. Mickiewicza R 28 Czarnacka Katarzyna Skłodowskiej N 29 Czarnacki Grzegorz ul. Kosmonautów 30 Czarnacki Piotr 1 Maja N 31 Czarnacki Andrzej Jasionka 32 Czerska Monika ul. Sportowa 33 Dąbrowska Elżbieta ul. Langiewicza 34 Dąbrowska Renata Wiśniowa N 35 Dąbrowska Ewelina Dworcowa N 36 Dąbrowska Joanna Koczergi 37 Dębowczyk Renata Brudno N 38 Domańska Urszula Brudno N 39 Domański Artur Laski 40 Duda Andrzej Zaniówka 41 Dudzińska Marta Jasionka 42 Dudziński Marian Siedliki N 43 Dyduch Mirosław ul. Kolejowa 44 Dzięcioł Ewa ul. Dworcowa 45 Dziwisz Elżbieta Rolna N 46 Eksmond Marian Koczergi N 47 Fic Alina Mickiewicza N 48 Filipowicz Wiesław Koczergi R 49 Flasiński Jacek Babianka 50 Furman Andrzej Zaniówka 51 Furman Grzegorz ul. Konopnickiej 52 Furmaniuk Łucja ul. Nadwalna 53 Gawryszuk Elżbieta Kolejowa 54 Gierliński Jerzy Kleeberga N 55 Golonka Jacek Tartaczna N 56 Golonka Magdalena Siedliki 57 Gołacki Wiesław Armii Ludowej 58 Gozdur Andrzej ul. -

{Journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA in THIS ISSUE 2 2

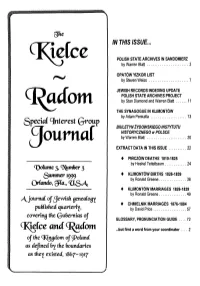

/N TH/S /SSUE... POLISH STATE ARCHIVES IN SANDOMIERZ by Warren Blatt 3 OPATÔWYIZKORLIST by Steven Weiss 7 JEWISH RECORDS INDEXING UPDATE POLISH STATE ARCHIVES PROJECT by Stan Diamond and Warren Blatt 1 1 THE SYNAGOGUE IN KLIMONTÔW by Adam Penkalla 1 3 Qpedd interest Qroup BIULETYN ZYDOWSKIEGOINSTYTUTU HISTORYCZNEGO w POLSCE {journal by Warren Blatt 2 0 EXTRACT DATA IN THIS ISSUE 2 2 • PINCZÔ W DEATHS 1810-182 5 by Heshel Teitelbaum 2 4 glimmer 1999 • KLIMONTÔ W BIRTHS 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 3 8 • KLIMONTÔ W MARRIAGES 1826-183 9 by Ronald Greene 4 9 o • C H Ml ELN IK MARRIAGES 1876-188 4 covering tfte Qufoernios of by David Price 5 7 and <I^ GLOSSARY, PRONUNCIATION GUIDE ... 72 ...but first a word from your coordinator 2 ojtfk as <kpne as tfie^ existed, Kieke-Radom SIG Journal, VoL 3 No. 3 Summer 1999 ... but first a word from our coordinator It has been a tumultuous few months since our last periodical. Lauren B. Eisenberg Davis, one of the primary founders of our group, Special Merest Group and the person who so ably was in charge of research projects at the SIG, had to step down from her responsibilities because of a serious journal illness in her family and other personal matters. ISSN No. 1092-800 6 I remember that first meeting in Boston during the closing Friday ©1999, all material this issue morning hours of the Summer Seminar. Sh e had called a "birds of a feather" meeting for all those genealogists interested in forming a published quarterly by the special interest group focusing on the Kielce and Radom gubernias of KIELCE-RADOM Poland. -

The Mineral Industries of Central Europe in 2003

THE MINERAL INDUSTRIES OF CENTRAL EUROPE CZECH REPUBLIC, HUNGARY, POLAND, AND SLOVAKIA By Walter G. Steblez The Central European transitional economy countries of privatization of the iron and steel sector continued to be a the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia represent dominant issue in the country’s mineral industry. one of the more economically dynamic regions of the former centrally planned economy countries of Europe and Central Government Policies and Programs Eurasia. As founding members of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovenia joined in The Government continued policies of economic development 1999), these countries have continued to implement policies that were aimed at integrating the country into the European designed to harmonize standards and trade with a view to Union (EU). The country’s membership in the International integrate themselves fully into the European Union (EU), Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation as they had done already in the European security sphere and Development (OECD), the World Bank for Reconstruction through membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. and Development, and the World Trade Organization, as well To accommodate new standards, the development of new as participation in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade commercial infrastructure in the region has added special was largely an outcome of the Czech Republic’s full orientation importance to the region’s cement and steel industries; major toward a Western European political system and market economy. consumption increases of these commodities serve as markers Three constituent acts comprise the country’s mining law, for likely consumption increases of base metals and many other which forms the foundation of the Government’s mining and mineral commodity groups. -

Gazeta Fall/Winter 2018

The site of the Jewish cemetery in Głowno. Photograph from the project Currently Absent by Katarzyna Kopecka, Piotr Pawlak, and Jan Janiak. Used with permission. Volume 25, No. 4 Gazeta Fall/Winter 2018 A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Tressa Berman, Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Antony Polonsky, Adam Schorin, Maayan Stanton, Agnieszka Ilwicka, William Zeisel, LaserCom Design. CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 2 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 3 FEATURES The Minhag Project: A Digital Archive of Jewish Customs Nathaniel Deutsch ................................................................................................................. 4 Teaching Space and Place in Holocaust Courses with Digital Tools Rachel Deblinger ................................................................................................................... 7 Medicinal Plants of Płaszów Jason Francisco .................................................................................................................. 10 REPORTS Independence March Held in Warsaw Amid Controversy Adam Schorin ...................................................................................................................... 14 Explaining Poland to the World: Notes from Poland Daniel Tilles -

Gminny Program Rewitalizacji Dla Gminy Szczucin Na Lata 2016-2026

GMINNY PROGRAM REWITALIZACJI DLA GMINY SZCZUCIN NA LATA 2016-2026 Aktualizacja – styczeń 2020 r. Gminny Program Rewitalizacji dla Gminy Szczucin na lata 2016-2026 Zespół autorski: Zespół autorów pod kierownictwem mgr inż. Wojciecha Kuska mgr inż. Agnieszka Bolingier mgr inż. Grzegorz Markowski mgr inż. Małgorzata Płotnicka mgr inż. Janusz Pietrusiak mgr inż. Agata Bechta mgr inż. Michał Drabek Opieka ze strony Zarządu – mgr inż. Barbara Markiel i mgr inż. Janusz Pietrusiak 2 Gminny Program Rewitalizacji dla Gminy Szczucin na lata 2016-2026 Spis treści Wykaz skrótów i pojęć ......................................................................................................................... 5 1. Wprowadzenie ............................................................................................................................ 7 1.1. Wstęp ...................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Powiązania GPR z dokumentami strategicznymi i planistycznymi Gminy................................... 9 3. Ogólna charakterystyka Gminy Szczucin ................................................................................... 15 3.1. Sfera przestrzenno – funkcjonalna ........................................................................................ 15 3.2. Sfera gospodarcza ................................................................................................................. 24 3.3. Sfera środowiskowa ............................................................................................................. -

Lelov: Cultural Memory and a Jewish Town in Poland. Investigating the Identity and History of an Ultra - Orthodox Society

Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Item Type Thesis Authors Morawska, Lucja Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 03/10/2021 19:09:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/7827 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Lucja MORAWSKA Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and International Studies University of Bradford 2012 i Lucja Morawska Lelov: cultural memory and a Jewish town in Poland. Investigating the identity and history of an ultra - orthodox society. Key words: Chasidism, Jewish History in Eastern Europe, Biederman family, Chasidic pilgrimage, Poland, Lelov Abstract. Lelov, an otherwise quiet village about fifty miles south of Cracow (Poland), is where Rebbe Dovid (David) Biederman founder of the Lelov ultra-orthodox (Chasidic) Jewish group, - is buried. -

Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich Polin Raport Roczny

MUZEUM HISTORII ŻYDÓW POLSKICH POLIN RAPORT ROCZNY POLIN MUSEUM OF THE HISTORY OF POLISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 polin.pl 1 2 Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Wspólna instytucja kultury / Joint Institution of Culture MUZEUM HISTORII ŻYDÓW POLSKICH POLIN RAPORT ROCZNY POLIN MUSEUM OF THE HISTORY OF POLISH JEWS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Wydawca / Publisher: Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN / POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews ISBN: 978-83-957601-0-5 Warszawa 2020 Redakcja / editor: Dział Komunikacji Muzeum POLIN / Communications Department, POLIN Museum Projekt graficzny, skład i przygotowanie do druku / Layout, typesetting: Piotr Matosek Tłumaczenie / English translation: Zofia Sochańska Korekta wersji polskiej / proofreading of the Polish version: Tamara Łozińska Fotografie / Photography: Muzeum POLIN / Photos: POLIN Museum 6 Spis treści / Table of content Muzeum, które zaciekawia ludzi... innymi ludźmi / Museum which attracts people with… other people 8 W oczekiwaniu na nowy rozdział / A new chapter is about to begin 10 Jestem w muzeum, bo... / I have came to the Museum because... 12 Wystawa stała / Core exhibition 14 Wystawy czasowe / Temporary exhibitions 18 Kolekcja / The collection 24 Edukacja / Education 30 Akcja Żonkile / The Daffodils campaign 40 Działalność kulturalna / Cultural activities 44 Scena muzyczna / POLIN Music Scene 52 Do muzeum z dziećmi / Children at the Museum 60 Żydowskość od kuchni / In the Jewish kitchen and beyond 64 Muzeum online / On-line Museum 68 POLIN w terenie / POLIN en route 72 Działalność naukowa / Academic activity 76 Nagroda POLIN / POLIN Award 80 Darczyńcy / Donors 84 Zespół Muzeum i wolontariusze / Museum team and volunteers 88 Muzeum partnerstwa / Museum of partnership 92 Bądźmy w kontakcie! / Let us stay in touch! 94 7 Muzeum, które zaciekawia ludzi.. -

„STRATEGIA ROZWOJU GMINY Parczew” 2014-2020

2014 SRGP 2014-2020 0 STRATEGIA ROZWOJU GMINY PARCZEW 2014-2020 oprac. esse Agnieszka Smreczyńska-Gąbka [SRGP 2014-2020] Na zlecenie Gminy Parczew, umowa z dnia 2 stycznia 2014r. SRGP 2014-2020 1 SPIS TREŚCI: I. Diagnoza gminy. I.1. Aktualny stan rozwoju gminy. I.1.a. Diagnoza społeczno – gospodarcza. I.1.b. Wyniki badań wewnętrznych i zewnętrznych oraz konsultacji. (Raport z badań cz. I; Bilans strategiczny cz. II – załącznik) I. 2. Analiza czynników rozwojowych gminy Parczew w oparciu o metodologię SWOT. I.2.a. Atuty i kluczowe problemy (bariery rozwojowe). I.2.b. Określenie zewnętrznych uwarunkowań odnoszących się do możliwości rozwoju. II. Misja gminy. III. Wizja strategiczna. III. 1. System wartości i aspiracji. III. 2. Wyróżnik budujący przewagę konkurencyjną gminy. III. 3. Cel główny. IV. Obszary kluczowe – cele strategiczne. V. Cele tematyczne – kierunkowe. VI. Cele szczegółowe/operacyjne – priorytety inwestycyjne. VII. Plan wdrażania, monitorowania strategii. VIII. Rekomendacje i odwoływanie się do dokumentów strategicznych. IX. Wskazania w zakresie komunikacji społecznej i promocji. SRGP 2014-2020 0 I. DIAGNOZA GMINY. I.1. AKTUALNY STAN ROZWOJU GMINY I. 2. ANALIZA CZYNNIKÓW ROZWOJOWYCH GMINY PARCZEW w oparciu o metodologię SWOT. I.1.a. DIAGNOZA I.1.b. WYNIKI BADAŃ I.2.a. ATUTY I KLUCZOWE PROBLEMY I.2.b. OKREŚLENIE ZEWNĘTRZNYCH UWARUNKOWAŃ SPOŁECZNO WEW. i ZEW. (BARIERY ROZWOJOWE) ODNOSZĄCYCH SIĘ DO MOŻLIWOŚCI ROZWOJU. GOSPODARCZA. ORAZ KONSULTACJI. II. MISJA GMINY. III. 1. III. WIZJA STRATEGICZNA. III. 2. SYSTEM WARTOŚCI III. 3. CEL GŁÓWNY. WRÓŻNIK BUDUJĄCY I ASPIRACJI. PRZEWAGĘ KONKURENCYJNĄ GMINY. IV. OBSZARY KLUCZOWE – CELE STRATEGICZNE OBSZAR/CEL NR. I. OBSZAR/CEL NR. II. OBSZAR/CEL NR. -

Two Awards for POLIN Museum in the SY- BILLA Competition

Two Awards for POLIN Museum in the SY- BILLA Competition The Warsaw Ghetto Museum would like to congratulate the Virtual Shtetl portal and POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. The Museum received two awards in the SYBILLA competition for the Museum Event of the Year – honouring the achievements of Polish museology and organized by The National Institute for Museums and Public Collections – for the Virtual Shtetl portal and for the social and educational Daffodils Campaign and the Łączy Nas Pamięć [The Memory Connects Us] concert implemented as part of the 75th anniversary of the outbreak of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. This year, prizes were awarded in six categories and the Grand Prix, which was received by the Museum of Architecture in Wrocław for the temporary exhibition of Leon Tarasewicz. This is a change compared to the last editions, when 11 prizes were awarded. The aim of the SYBILLA competition is to award people and institutions praiseworthy for their care and protection of Polish cultural heritage. On this occasion, we are talking to Mr Albert Stankowski, Director of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum and originator and the first coordinator of the honoured portal about its origins, the potential inherent in voluntary service and the growing interest in the culture and history of Polish Jews. What was the knowledge of the Jewish history of our – once – neighbours in 2009, when you were creating the Virtual Shtetl? First of all, I would like to congratulate POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews for the award received for the Virtual Shtetl portal in the SYBILLA Competition for the Museum Event of the Year. -

Wykaz Obwodów Łowieckich

Zał ącznik nr 1 do Uchwały Nr VIII/92/07 Sejmiku Województwa Małopolskiego z dnia 28 maja 2007 r. Wykaz obwodów łowieckich Poprzedni 1 Obszar Numer numer Nazwa Obwodu obwodu Opisy granic obwodów łowieckich obwodu obwodu (ha) 1 1 Zaryszyn 3444 Północna granica obwodu biegnie od szosy Kraków - Kielce drog ą w kierunku wschodnim do wsi Droblin (jednocze śnie granic ą województwa małopolskiego). St ąd granic ą województwa na południowy wschód dochodzi do skraju kompleksu le śnego i dalej na południe do drogi le śnej biegn ącej granic ą województwa (jednocze śnie granic ą Nadle śnictw: Miechów i Pi ńczów) do północno zachodniego kra ńca wsi Sadki. Nast ępnie drog ą na południowy wschód, przez wie ś Sadki dochodzi do osiedla Bugaj i ponownie do granicy województwa. Dalej granic ą województwa, najpierw na wschód do skraju lasu, nast ępnie skrajem lasu na południe, przecinaj ąc szos ę Zaryszyn -Wola Knyszy ńska, skrajem nast ępnego kompleksu le śnego dochodzi do drogi biegn ącej przez Trzonów. Drog ą t ą na zachód przez Trzonów i dalej przez Ksi ąż Mały do Zygmuntowa. St ąd granica biegnie skrajem lasu Brzozówki na północ, dalej na zachód do szosy Kraków - Kielce i szos ą t ą przez Moczydło do drogi na Droblin i punktu pocz ątkowego. 2 2 Kozłów 4495 Północna granica obwodu biegnie rzek ą Mierzawa od przeci ęcia si ę z torem kolejowym Tunel - S ędziszów do szosy Kozłów - Wierzbica i tą drog ą do wschodniego kra ńca miejscowo ści Klimontów i dalej drog ą Klimontów - Pękosław do przeci ęcia si ę z granic ą gminy Wodzisław, sk ąd na południowy wschód t ą granic ą do granicy województwa małopolskiego. -

The Condition of Sanitary Infrastructure in the Parczew District and the Need for Its Development

Journal of Ecological Engineering Received: 2018.05.01 Accepted: 2018.06.15 Volume 19, Issue 5, September 2018, pages 107–115 Published: 2018.09.01 https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/92674 The Condition of Sanitary Infrastructure in the Parczew District and the Need for its Development Agnieszka Micek1, Michał Marzec1*, Karolina Jóźwiakowska2, Patrycja Pochwatka1 1 Department of Environmental Engineering and Geodesy, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Leszczyńskiego 7, 20-069 Lublin, Poland 2 Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Nowoursynowska 166, 02-787 Warszawa, Poland * Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is to present the current state and the need for development of sanitary infrastructure in the communes of Parczew District, in Lublin Voivodeship. Parczew District encompasses seven communes: Parczew, Dębowa Kłoda, Jabłoń, Milanów, Podedwórze, Siemień, and Sosnowica. The present paper uses the data from the surveys conducted in these communes in 2016. On average, 88% of the population used the water supply system in the communes surveyed, while 48% of the inhabitants were connected to a sewerage system. Parczew District had 12 collective mechanical and biological wastewater treatment plants with a capacity exceeding 5 m3/d. The households which were not connected to the sewerage network discharged the wastewater mainly to non-return tanks. In the communes surveyed, 1,115 households had domestic wastewater treatment plants. All of them were systems with infiltration drainage, which do not ensure high efficiency of removing pollutions and may even contribute to the degradation of the groundwater quality. In order to solve the existing problems of sewage and water management in the communes of Parczew District, it is necessary to further develop the collective sewerage systems and equip the areas which have a dispersed development layout with highly efficient domestic treatment plants, such as constructed wetlands. -

Wyjątkowy Dzień Kobiet "Kobieta Wnosi Coś, Co Powoduje, Że Bez Niej Świat Nie Byłby Taki Sam

Wyjątkowy Dzień Kobiet "Kobieta wnosi coś, co powoduje, że bez niej świat nie byłby taki sam. To ona daje har - monię, uczy nas łagodności, delikatnej miłości i sprawia, że świat jest piękniejszy" Papież Franciszek 8 marca przypada święto, które jednoczy kobiety, mobilizuje mężczyzn i skłania do re - fleksji nad fenomenem kobiecości. Kobieta od lat była fundamentem ogniska domowego, ale także inspiracją artystów, poetów, malarzy, kompozytorów. str. 13 numer 3 / kwiecień 2017 kwartalnik bezpłatny - Reforma oświaty str. 2 - Nasz Profesor str. 3 - Znany malarz ze Szczucina str. 4 - 25 finał WOŚP str. 5 - Gminny Program Rewitalizacji str. 9 - VII Koncert Noworoczny Orkiestry Dętej str. 11 - Szkolne Echa str.16-19 - Kącik kulinarny str. 23 WOŚP Rada Seniorów str. 9 Adres redakcji: 33-230 Szczucin, ul. Kościuszki 32 e-mail: [email protected] Redaktor Naczelna: Krystyna Szymańska Oddajemy w ręce mieszkańców Gminy Szczucin bezpłatny kwartalnik informacyjny. Druk: Drukarnia w Tarnobrzegu Zachęcamy do współpracy z redakcją, celem włączenia się w tworzenie naszej gazety. str.2 3 / 2017 Nie zapominamy także i poruszania się po drogach (w o działaniach związanych z ter - 2017 roku udało się wykonać 5,67 Z myślą o dalszym rozwoju w naszej Gminie momodernizacją obiektów zwią - km dróg). Okres realizacji pro - zanych z edukacją. Na chwilę jektu kończy się w bieżącym O tym, że dalszy rozwój cować i rozwijać się zawodowo. inwestycyjne związane z moder - obecną czekamy na rozstrzy roku. Gminy jest możliwy i planowany Rewitalizacja zabytkowego XVII nizacją budynków Ochotniczych gnięcie złożonych przez Gminę Po przedstawionych pla - świadczą ostatnio podjęte działa - wiecznego parku typu krajobra - Straży Pożarnych w Zabrniu i Su - Szczucin wniosków o dofinanso - nach inwestycyjnych celujących nia inwestycyjne, które planujemy zowego w Szczucinie - realizacja chym Gruncie.