Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Put Kurtz on the Congo? Harry White, Irving L

Who Put Kurtz on the Congo? Harry White, Irving L. Finston Conradiana, Volume 42, Number 1-2, Spring/Summer 2010, pp. 81-92 (Article) Published by Texas Tech University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/cnd.2010.0010 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/452495 Access provided at 9 Oct 2019 05:10 GMT from USP-Universidade de São Paulo Who Put Kurtz on the Congo? HARRYWHITEANDIRVINGL.FINSTON Our article included in this issue, “The Two River Narratives in ‘Heart of Darkness,’” showed that Joseph Conrad imagined Kurtz’s Inner Station to be located on the Kasai River and not on the Congo as has been gener- ally assumed. We now ask how one of the most important, influential, and widely read and studied works of modern fiction has been so con- sistently and unquestioningly misread for so long on such a basic level. In what follows we show that something akin to a cover-up was initi- ated by the author regarding the location and direction of Charlie Mar- low’s voyage. We will then reveal the primary source for many of the current interpretations and misinterpretations of “Heart of Darkness” by showing how one very influential scholar was the first to place Kurtz’s station on the wrong river. Nowhere in any of his writings did Conrad report that Marlow’s venture into the heart of darkness followed his own voyage from Stan- ley Pool to Stanley Falls. Nowhere in “Heart of Darkness” does it say that Marlow voyages up the Congo to find Kurtz. -

Cultural Analysis an Interdisciplinary Forum on Folklore and Popular Culture

CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 17.1 Cover image courtesy of Beate Sløk-Andersen CULTURAL ANALYSIS AN INTERDISCIPLINARY FORUM ON FOLKLORE AND POPULAR CULTURE Vol. 17.1 © 2019 by The University of California Editorial Board Pertti J. Anttonen, University of Eastern Finland, Finland Hande Birkalan, Yeditepe University, Istanbul, Turkey Charles Briggs, University of California, Berkeley, U.S.A. Anthony Bak Buccitelli, Pennsylvania State University, Harrisburg, U.S.A. Oscar Chamosa, University of Georgia, U.S.A. Chao Gejin, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, China Valdimar Tr. Hafstein, University of Iceland, Reykjavik Jawaharlal Handoo, Central Institute of Indian Languages, India Galit Hasan-Rokem, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem James R. Lewis, University of Tromsø, Norway Fabio Mugnaini, University of Siena, Italy Sadhana Naithani, Jawaharlal Nehru University, India Peter Shand, University of Auckland, New Zealand Francisco Vaz da Silva, University of Lisbon, Portugal Maiken Umbach, University of Nottingham, England Ülo Valk, University of Tartu, Estonia Fionnuala Carson Williams, Northern Ireland Environment Agency Ulrika Wolf-Knuts, Åbo Academy, Finland Editorial Collective Senior Editors: Sophie Elpers, Karen Miller Associate Editors: Andrea Glass, Robert Guyker, Jr., Semontee Mitra Review Editor: Spencer Green Copy Editors: Megan Barnes, Jean Bascom, Nate Davis, Cory Hutcheson, Alice Markham-Cantor, Anna O’Brien, Joy Tang, Natalie Tsang Website Manager: Kiesha Oliver Table of Contents -

The New Age Under Orage

THE NEW AGE UNDER ORAGE CHAPTERS IN ENGLISH CULTURAL HISTORY by WALLACE MARTIN MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS BARNES & NOBLE, INC., NEW YORK Frontispiece A. R. ORAGE © 1967 Wallace Martin All rights reserved MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 316-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13, England U.S.A. BARNES & NOBLE, INC. 105 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner Ltd, Frome and London This digital edition has been produced by the Modernist Journals Project with the permission of Wallace T. Martin, granted on 28 July 1999. Users may download and reproduce any of these pages, provided that proper credit is given the author and the Project. FOR MY PARENTS CONTENTS PART ONE. ORIGINS Page I. Introduction: The New Age and its Contemporaries 1 II. The Purchase of The New Age 17 III. Orage’s Editorial Methods 32 PART TWO. ‘THE NEW AGE’, 1908-1910: LITERARY REALISM AND THE SOCIAL REVOLUTION IV. The ‘New Drama’ 61 V. The Realistic Novel 81 VI. The Rejection of Realism 108 PART THREE. 1911-1914: NEW DIRECTIONS VII. Contributors and Contents 120 VIII. The Cultural Awakening 128 IX. The Origins of Imagism 145 X. Other Movements 182 PART FOUR. 1915-1918: THE SEARCH FOR VALUES XI. Guild Socialism 193 XII. A Conservative Philosophy 212 XIII. Orage’s Literary Criticism 235 PART FIVE. 1919-1922: SOCIAL CREDIT AND MYSTICISM XIV. The Economic Crisis 266 XV. Orage’s Religious Quest 284 Appendix: Contributors to The New Age 295 Index 297 vii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS A. R. Orage Frontispiece 1 * Tom Titt: Mr G. Bernard Shaw 25 2 * Tom Titt: Mr G. -

Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction

In the Wake of Conrad: Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction Alexandra Caroline Phillips BA (Hons) Cardiff University, MA King’s College, London A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff University 30 March 2015 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction - Contexts and Tradition 5 The Transition from Sail to Steam 6 The Maritime Fiction Tradition 12 The Changing Nature of the Sea Story in the Twentieth Century 19 PART ONE Chapter 1 - Re-Reading Conrad and Maritime Fiction: A Critical Review 23 The Early Critical Reception of Conrad’s Maritime Texts 24 Achievement and Decline: Re-evaluations of Conrad 28 Seaman and Author: Psychological and Biographical Approaches 30 Maritime Author / Political Novelist 37 New Readings of Conrad and the Maritime Fiction Tradition 41 Chapter 2 - Sail Versus Steam in the Novels of Joseph Conrad Introduction: Assessing Conrad in the Era of Steam 51 Seamanship and the Sailing Ship: The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ 54 Lord Jim, Steam Power, and the Lost Art of Seamanship 63 Chance: The Captain’s Wife and the Crisis in Sail 73 Looking back from Steam to Sail in The Shadow-Line 82 Romance: The Joseph Conrad / Ford Madox Ford Collaboration 90 2 PART TWO Chapter 3 - A Return to the Past: Maritime Adventures and Pirate Tales Introduction: The Making of Myths 101 The Seduction of Silver: Defoe, Stevenson and the Tradition of Pirate Adventures 102 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Tales of Captain Sharkey 111 Pirates and Petticoats in F. Tennyson Jesse’s -

Bradmore Lunches

ABBOTT William Abbot of Bradmore received lease from Sir John Willughby 30.6.1543. Robert Abbot married Alice Smyth of Bunny at Bunny 5.10.1566. Henry Sacheverell of Ratcliffe on Soar, Geoffrey Whalley of Idersay Derbyshire, William Hydes of Ruddington, Robert Abbotte of Bradmore, John Scotte the elder, son and heir of late Henry Scotte of Bradmore, and John Scotte the younger, son and heir of Richard Scotte of Bradmore agree 7.1.1567 to levy fine of lands, tenements and hereditaments in Bradmore, Ruddington and Cortlingstocke to William Kinder and Richard Lane, all lands, tenements and hereditaments in Bradmore to the sole use of Geoffrey Walley, and in Ruddington and 1 cottage and land in Bradmore to the use of Robert Abbotte for life and after his death to Richard Hodge. Alice Abbott married Oliver Martin of Normanton at Bunny 1.7.1570. James Abbot of Bradmore 20.10.1573, counterpart lease from Frauncis Willughby Ann Abbott married Robert Dawson of Bunny at Bunny 25.10.1588. Robert Abbot, of Bradmore? married Dorothy Walley of Bradmore at Bunny 5.10.1589. Margery Abbott married Jarvis Hall/Hardall of Ruddington at Bunny 28.11.1596. William Abbot of Bradmore, husbandman, married Jane Barker of Bradmore, widow, at Bunny 27.1.1600, licence issued 19.1.1600. 13.1.1613 John Barker of Newark on Trent, innholder, sold to Sir George Parkyns of Bunny knight and his heirs 1 messuage or tenement in Bradmere now or late in the occupation of William Abbott and Jane his wife; John Barker and his wife Johane covenant to acknowledge a fine of the premises within 7 years. -

Mapping Topographies in the Anglo and German Narratives of Joseph Conrad, Anna Seghers, James Joyce, and Uwe Johnson

MAPPING TOPOGRAPHIES IN THE ANGLO AND GERMAN NARRATIVES OF JOSEPH CONRAD, ANNA SEGHERS, JAMES JOYCE, AND UWE JOHNSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristy Rickards Boney, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Helen Fehervary, Advisor Professor John Davidson Professor Jessica Prinz Advisor Graduate Program in Professor Alexander Stephan Germanic Languages and Literatures Copyright by Kristy Rickards Boney 2006 ABSTRACT While the “space” of modernism is traditionally associated with the metropolis, this approach leaves unaddressed a significant body of work that stresses non-urban settings. Rather than simply assuming these spaces to be the opposite of the modern city, my project rejects the empty term space and instead examines topographies, literally meaning the writing of place. Less an examination of passive settings, the study of topography in modernism explores the action of creating spaces—either real or fictional which intersect with a variety of cultural, social, historical, and often political reverberations. The combination of charged elements coalesce and form a strong visual, corporeal, and sensory-filled topography that becomes integral to understanding not only the text and its importance beyond literary studies. My study pairs four modernists—two writing in German and two in English: Joseph Conrad and Anna Seghers and James Joyce and Uwe Johnson. All writers, having experienced displacement through exile, used topographies in their narratives to illustrate not only their understanding of history and humanity, but they also wrote narratives which concerned a larger global ii community. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82353-1 - Suspense Joseph Conrad Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION OF THE WORKS OF JOSEPH CONRAD © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82353-1 - Suspense Joseph Conrad Frontmatter More information SUSPENSE © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82353-1 - Suspense Joseph Conrad Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION OF THE WORKS OF JOSEPH CONRAD General Editors J. H. Stape and Allan H. Simmons St Mary’s University College, Twickenham, London Editorial Board Laurence Davies, University of Glasgow Alexandre Fachard, UniversitedeLausanne´ Jeremy Hawthorn, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology Owen Knowles, University of Hull Linda Bree, Cambridge University Press Textual Advisor Robert W. Trogdon, Institute for Bibliography and Editing Kent State University Founding Editors †Bruce Harkness Marion C. Michael Norman Sherry Chief Executive Editor (1985–2008) †S. W. Reid © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82353-1 - Suspense Joseph Conrad Frontmatter More information JOSEPH CONRAD SUSPENSE edited by Gene M. Moore © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82353-1 - Suspense Joseph Conrad Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru,UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521823531 This, the Cambridge Edition text of Suspense, now correctly established from the original sources and first published in 2011 C the Estate of Joseph Conrad 2011. -

Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON

THEATER EMORY A Complete Production History 2018-2019 SEASON Three Productions in Rotating Repertory The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity October 23-24, November 3-4, 8-9 • Written by Kristoffer Diaz • Directed by Lydia Fort A satirical smack-down of culture, stereotypes, and geopolitics set in the world of wrestling entertainment. Mary Gray Munroe Theater We Are Proud to Present a Presentation About the Herero of Namibia, Formerly Known as Southwest Africa, From the German Südwestafrika, Between the Years 1884-1915 October 25-26, 30-31, November 10-11 • Written by Jackie Sibblies Drury • Directed by Eric J. Little The story of the first genocide of the twentieth century—but whose story is actually being told? Mary Gray Munroe Theater The Moors October 27-28, November 1-2, 6-7 • Written by Jen Silverman • Directed by Matt Huff In this dark comedy, two sisters and a dog dream of love and power on the bleak English moors. Mary Gray Munroe Theater Sara Juli’s Tense Vagina: an actual diagnosis November 29-30 • Written, directed, and performed by Sara Juli Visiting artist Sara Juli presents her solo performance about motherhood. Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Tatischeff Café April 4-14 • Written by John Ammerman • Directed by John Ammerman and Clinton Wade Thorton A comic pantomime tribute to great filmmaker and mime Jacques Tati Mary Gray Munroe Theater 2 2017-2018 SEASON Midnight Pillow September 21 - October 1, 2017 • Inspired by Mary Shelley • Directed by Park Krausen 13 Playwrights, 6 Actors, and a bedroom. What dreams haunt your midnight pillow? Theater Lab, Schwartz Center for the Performing Arts The Anointing of Dracula: A Grand Guignol October 26 - November 5, 2017 • Written and directed by Brent Glenn • Inspired by the works of Bram Stoker and others. -

The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Joseph Conrad

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82407-1 - Joseph Conrad: Under Western Eyes Edited by Roger Osborne and Paul Eggert Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION OF THE WORKS OF JOSEPH CONRAD © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82407-1 - Joseph Conrad: Under Western Eyes Edited by Roger Osborne and Paul Eggert Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82407-1 - Joseph Conrad: Under Western Eyes Edited by Roger Osborne and Paul Eggert Frontmatter More information UNDER WESTERN EYES © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82407-1 - Joseph Conrad: Under Western Eyes Edited by Roger Osborne and Paul Eggert Frontmatter More information THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION OF THE WORKS OF JOSEPH CONRAD General Editors J. H. Stape and Allan H. Simmons St Mary’s University College, Twickenham, London Editorial Board Laurence Davies, University of Glasgow Alexandre Fachard, UniversitedeLausanne´ Robert Hampson, Royal Holloway, University of London Jeremy Hawthorn, The Norwegian University of Science and Technology Owen Knowles, University of Hull Linda Bree, Cambridge University Press Textual Advisor Robert W. Trogdon, Institute for Bibliography and Editing Kent State University Founding Editors †Bruce Harkness Marion C. Michael Norman Sherry Chief Executive Editor (1985–2008) †S. W. Reid © in this web service Cambridge University -

1. Thomas Moser, Joseph Coilrad: Achieveme"T and Decline (Cambridge, Conrad: Pola"D's Eilglish Getlius (Cambridge

Notes Notes to the Introduction 1. Thomas Moser, Joseph COIlrad: Achieveme"t and Decline (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1957) p. 10; M. C. Bradbrook, Joseph Conrad: Pola"d's EIlglish Getlius (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1941); Morton Zabel, TI.e Portable Conrad (New York: Viking, 1947); F. R. Leavis, The Great Traditioll (London: Chatto " Windus, 1948). A. J. Guerard's monograph Josepl. Conrad (New York: New Directions, 1947) should be added to this list. 2. (a) Richard Curle, Josepl. Cotlrad: A Study (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner, 1914); Wilson Follett, Joseph Conrad: A Short Study. (b) Ford Madox Ford, Josepl. COllrad: A Personal Remembrance (London: Duckworth, 1924); Richard Curle, The Last Twelve Years of Joseph Conrad (London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1928); Jessie Conrad, Joseph Conrad as I KIlew Him (London: Heinemann, 1926) and Joseph Conrad and his Circle (London: Jarrolds, 1935). (c) Five Letters by Joseph Cotlrad to Edward Noble in 1895 (privately printed, 1925); Joseph Co"rad's Letters to his Wife (privately printed, 1927); Conrad to a Friend: 150 Selected Letters from Joseph COllrad to Richard Curle, ed. R. Curle (London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1928); Letters from Joseph Conrad, 1895 to 1924, ed. Edward Garnett (London: Nonesuch Press, 1928); Joseph Conrad: Life alld Letters, ed. G. Jean-Aubry (London: Heinemann, 1927) - hereafter referred to as L.L. 3. Gustav Morf, The Polish Heritage of Joseph Conrad (London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1930); R. L. M~groz,Joseph Conrad's Milld and Method (London: Faber" Faber, 1931); Edward Crankshaw, Josepll Conrad: Some Aspects of tl.e Art of tl.e Novel (London: The Bodley Head, 1936); J. -

A Good Soldier Or Random Exposure? a Stochastic Accumulating Mechanism to Explain Frequent Citizenship

A GOOD SOLDIER OR RANDOM EXPOSURE? A STOCHASTIC ACCUMULATING MECHANISM TO EXPLAIN FREQUENT CITIZENSHIP By Christopher R. Dishop A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Psychology—Doctor of Philosophy 2020 ABSTRACT A GOOD SOLDIER OR RANDOM EXPOSURE? A STOCHASTIC ACCUMULATING MECHANISM TO EXPLAIN FREQUENT CITIZENSHIP By Christopher R. Dishop The term, “good soldier,” refers to an employee who exhibits sustained, superior citizenship relative to others. Researchers have argued that this streaky behavior is due to motives, personality, and other individual characteristics such as one’s justice perceptions. What is seldom acknowledged is that differences across employees in their helping behavior may also reflect differences in the number of requests that they receive asking them for assistance. To the extent that incoming requests vary across employees, a citizenship champion could emerge even among those who are identical in character. This study presents a situation by person framework describing how streaky citizenship may be generated from the combination of context (incoming requests for help) and person characteristics (reactions to such requests). A pilot web-scraping study examines the notifications individuals receive asking them for help. The observed empirical pattern is then implemented into an agent-based simulation where person characteristics and responses can be systematically controlled and manipulated. The results suggest that employee helping behaviors, in response to pleas for assistance, may exhibit sustained differences even if employees do not differ a priori in motive or character. Theoretical and practical implications, as well as study limitations, are discussed. I dedicate this dissertation to four family members who made my education possible. -

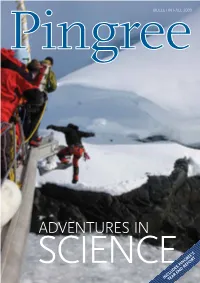

Adventures In

BULLETIN Fall 2009 adventurEs in sCIENCE Ingree’sPort IncludesYear end P re board of trustees 2008–09 Jane Blake Riley ’77, p ’05 President contents James D. Smeallie p ’05, ’09 V ice President Keith C. Shaughnessy p ’04, ’08, ’10 T reasurer Philip G. Lake ’85 4 Pingree Secretary athletes Thanks Anthony G.L. Blackman p ’10 receive Interim Head of School All-American Nina Sacharuk Anderson ’77, p ’09 ’11 honors for stepping up to the plate. Kirk C. Bishop p ’06, ’06, ’08 Tamie Thompson Burke ’76, p ’09 Patricia Castraberti p ’08 7 Malcolm Coates p ’01 Honoring Therese Melden p ’09, ’11 Reflections: Science Teacher Even in our staggering economy, Theodore E. Ober p ’12 from Head of School Eva Sacharuk 16 Oliver Parker p ’06, ’08, ’12 Dr. Timothy M. Johnson Jagruti R. Patel ’84 you helped the 2008–2009 Pingree William L. Pingree p ’04, ’08 3 Mary Puma p ’05, ’07, ’10 annual Fund hit a home run. Leslie Reichert p ’02, ’07 Patrick T. Ryan p ’12 William K. Ryan ’96 Binkley C. Shorts p ’95, ’00 • $632,000 raised Joyce W. Swagerty • 100% Faculty and staff participation Richard D. Tadler p ’09 William J. Whelan, Jr. p ’07, ’11 • 100% Board of trustees participation Sandra Williamson p ’08, ’09, ’10 Brucie B. Wright Guess Who! • 100% class of 2009 participation Pictures from Amy McGowan p ’07, ’10 the archives 26 • 100% alumni leadership Board participation Parents Association President William K. Ryan ’96 • 15% more donations than 2007–2008 A Lumni L eadership Board President Cover Story: • 251 new Pingree donors board of overseers Adventures in Science Alice Blodgett p ’78, ’81, ’82 Susan B.