Foraging Dispersion of Ryukyu Flying-Foxes and Relationships with Fig Abundance in East-Asian Subtropical Island Forests

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ctz78-02 (02) Lee Et Al.Indd 51 14 08 2009 13:12 52 Lee Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 78 (2) 51-64 (2009) Variation in the nocturnal foraging distribution of and resource use by endangered Ryukyu flying foxes(Pteropus dasymallus) on Iriomotejima Island, Japan Ya-Fu Lee1, 4, Tokushiro Takaso2, 5, Tzen-Yuh Chiang1, 6, Yen-Min Kuo1, 7, Nozomi Nakanishi2, 8, Hsy-Yu Tzeng3, 9, Keiko Yasuda2 1 Department of Life Sciences and Institute of Biodiversity, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan 2 The Iriomote Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, 671 Iriomote, Takatomi-cho, Okinawa 907- 1542, Japan 3 Hengchun Research Center, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Pingtung 946, Taiwan 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 E-mail: [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] 7 E-mail: [email protected] 8 E-mail: [email protected] 9 E-mail: [email protected] Key words: abundance, bats, Chiroptera, diet, figs, frugivores, habitat Abstract Contents The nocturnal distribution and resource use by Ryukyu flying foxes Introduction ........................................................................................ 51 was studied along 28 transects, covering five types of habitats, on Material and methods ........................................................................ 53 Iriomote Island, Japan, from early June to late September, 2005. Study sites ..................................................................................... 53 Bats were mostly encountered solitarily (66.8%) or in pairs (16.8%), Bat and habitat census ................................................................ -

The Influence of Invasive Alien Plant Control on the Foraging Habitat Quality of the Mauritian Flying Fox (Pteropus Niger)

Master’s Thesis 2017 60 ECTS Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management The influence of invasive alien plant control on the foraging habitat quality of the Mauritian flying fox (Pteropus niger) Gabriella Krivek Tropical Ecology and Natural Resource Management ACKNOWLEDMENTS First, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisors Torbjørn Haugaasen from INA and Vincent Florens from the University of Mauritius, who made this project possible and helped me through my whole study and during the write-up. I also want to thank to NMBU and INA for the financial support for my field work in Mauritius. I am super thankful to Maák Isti for helping with the statistical issues and beside the useful ideas and critical comments, sending me positive thoughts on hopeless days and making me believe in myself. Special thanks to Cláudia Baider from The Mauritius Herbarium, who always gave me useful advice on my drafts and also helped me in my everyday life issues. I would like to thank Prishnee for field assistance and her genuine support in my personal life as well. I am also grateful to Mr. Owen Griffiths for his permission to conduct my study on his property and to Ravi, who generously provided me transportation to the field station, whenever I needed. Super big thanks to Rikard for printing out and submitting my thesis. I am also thankful to my family for their support during my studies, fieldwork and writing, and also for supporting the beginning of a new chapter in Mauritius. Finally, a special mention goes to my love, who has been motivating me every single day not to give up on my dreams. -

WIAD CONSERVATION a Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity

WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity WIAD CONSERVATION A Handbook of Traditional Knowledge and Biodiversity Table of Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................... 2 Ohu Map ...................................................................................................................................... 3 History of WIAD Conservation ...................................................................................................... 4 WIAD Legends .............................................................................................................................. 7 The Story of Julug and Tabalib ............................................................................................................... 7 Mou the Snake of A’at ........................................................................................................................... 8 The Place of Thunder ........................................................................................................................... 10 The Stone Mirror ................................................................................................................................. 11 The Weather Bird ................................................................................................................................ 12 The Story of Jelamanu Waterfall ......................................................................................................... -

Phenology of Ficus Variegata in a Seasonal Wet Tropical Forest At

Joumalof Biogeography (I1996) 23, 467-475 Phenologyof Ficusvariegata in a seasonalwet tropicalforest at Cape Tribulation,Australia HUGH SPENCER', GEORGE WEIBLENI 2* AND BRIGITTA FLICK' 'Cape TribulationResearch Station, Private Mail Bag5, Cape Tribulationvia Mossman,Queensland 4873, Australiaand 2 The Harvard UniversityHerbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue,Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA Abstract. We studiedthe phenologyof 198 maturetrees dioecious species, female and male trees initiatedtheir of the dioecious figFicus variegataBlume (Moraceae) in a maximalfig crops at differenttimes and floweringwas to seasonally wet tropical rain forestat Cape Tribulation, some extentsynchronized within sexes. Fig productionin Australia, from March 1988 to February 1993. Leaf the female (seed-producing)trees was typicallyconfined productionwas highlyseasonal and correlatedwith rainfall. to the wet season. Male (wasp-producing)trees were less Treeswere annually deciduous, with a pronouncedleaf drop synchronizedthan femaletrees but reacheda peak level of and a pulse of new growthduring the August-September figproduction in the monthsprior to the onset of female drought. At the population level, figs were produced figproduction. Male treeswere also morelikely to produce continuallythroughout the study but there were pronounced figscontinually. Asynchrony among male figcrops during annual cyclesin figabundance. Figs were least abundant the dry season could maintainthe pollinatorpopulation duringthe early dry period (June-September)and most under adverseconditions -

Rainforest Disturbance Affects Population Density of the Northern Cassowary Casuarius Unappendiculatus in Papua, Indonesia

Rainforest disturbance affects population density of the northern cassowary Casuarius unappendiculatus in Papua, Indonesia M ARGARETHA P ANGAU-ADAM,MICHAEL M ÜHLENBERG and M ATTHIAS W ALTERT Abstract Nominally protected areas in Papua are under and human population growth are leading to high rates threat from encroachment, logging and hunting. The of deforestation and forest conversion. Besides disturbance northern cassowary Casuarius unappendiculatus is the from logging, large-scale oil palm plantations are the pri- largest frugivore of the lowland rainforest of New Guinea mary cause of the loss of lowland forest in Papua (Frazier, and is endemic to this region, and therefore it is an 2007). A number of conservation areas and protection important conservation target and a potential flagship forests have been established in this region (de Fretes, 2007) species. We investigated effects of habitat degradation on the but agricultural encroachment, illegal logging and hunting species by means of distance sampling surveys of 58 line by immigrants and local communities are common. As in transects across five distinct habitats, from primary forest to other parts of the tropics, local extinction of forest avifauna forest gardens. Estimated cassowary densities ranged from following forest fragmentation and extensive forest clearing −2 14.1 (95%CI9.2–21.4) birds km in primary forest to 1.4 is to be expected (Kattan et al., 1994; Castelletta et al., 2000; −2 (95%CI0.4–5.6) birds km in forest garden. Density Waltert et al., 2004). Large forest birds such as cassowaries estimates were intermediate in unlogged but hunted natural (Casuarius spp.) are particularly likely to disappear if forest and in . -

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites

Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites (Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Upper Marikina-Kaliwa Forest Reserve, Bago River Watershed and Forest Reserve, Naujan Lake National Park and Subwatersheds, Mt. Kitanglad Range Natural Park and Mt. Apo Natural Park) Philippines Biodiversity & Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy & Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) 23 March 2015 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. The Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience Program is funded by the USAID, Contract No. AID-492-C-13-00002 and implemented by Chemonics International in association with: Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. Ecological Assessments in the B+WISER Sites Philippines Biodiversity and Watersheds Improved for Stronger Economy and Ecosystem Resilience (B+WISER) Program Implemented with: Department of Environment and Natural Resources Other National Government Agencies Local Government Units and Agencies Supported by: United States Agency for International Development Contract No.: AID-492-C-13-00002 Managed by: Chemonics International Inc. in partnership with Fauna and Flora International (FFI) Haribon Foundation World Agroforestry Center (ICRAF) 23 March -

The Case of the Endangered Ryukyu Flying Fox

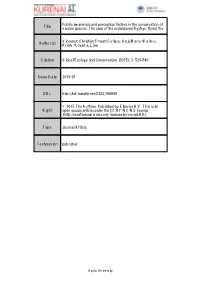

Public awareness and perceptual factors in the conservation of Title elusive species: The case of the endangered Ryukyu flying fox Vincenot, Christian Ernest; Collazo, Anja Maria; Wallmo, Author(s) Kristy; Koyama, Lina Citation Global Ecology and Conservation (2015), 3: 526-540 Issue Date 2015-01 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/196069 © 2015 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an Right open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Global Ecology and Conservation 3 (2015) 526–540 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Public awareness and perceptual factors in the conservation of elusive species: The case of the endangered Ryukyu flying fox Christian Ernest Vincenot a,∗, Anja Maria Collazo b, Kristy Wallmo c, Lina Koyama a a Department of Social Informatics, Graduate School of Informatics, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan b Graduate School of Human and Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan c National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA article info a b s t r a c t Article history: The success of biological conservation initiatives is not solely reliant on the collection of Received 23 October 2014 ecological information, but equally on public adherence to protection programs. Awareness Received in revised form 7 February 2015 and perception of target species condition the intensity and orientation of public involve- Accepted 7 February 2015 ment in conservation initiatives. Their evaluation is critical in the case of elusive animals, Available online 13 February 2015 for which incertitude surrounding public attitude is maximized. -

Isolation and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoid from Ficus Variegata Blume

538 Indones. J. Chem., 2019, 19 (2), 538 - 543 NOTE: Isolation and Evaluation of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Flavonoid from Ficus variegata Blume Rolan Rusli*, Bela Apriliana Ningsih, Agung Rahmadani, Lizma Febrina, Vina Maulidya, and Jaka Fadraersada Pharmacotropics Laboratory, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Mulawarman, Gunung Kelua, Samarinda 75119, East Kalimantan, Indonesia * Corresponding author: Abstract: Ficus variegata Blume is a specific plant of East Kalimantan. Flavonoid compound of F. variegata Blume was isolated by vacuum liquid and column tel: +62-85222221907 chromatography, with previously extracted by maceration method using n-hexane and email: [email protected] methanol, and fractionation using ethyl acetate solvent. The eluent used in isolation were Received: April 12, 2017 n-hexane:ethyl acetate (8:2). Based on the results of elucidation structure using Accepted: January 29, 2018 spectroscopy methods (GC-MS, NMR, and FTIR), 5-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxy-phenyl)-8,8- DOI: 10.22146/ijc.23947 dimethyl-8H-pyrano[2,3-f] chromen-4-one was obtained. This compound has antibacterial and antioxidant activity. Keywords: Ficus variegata Blume; flavonoid; antibacterial activities; antioxidant activity ■ INTRODUCTION much every time it produces fruit. Due that, this plant is a potential plant to be used as medicinal plant. Ficus is a genus that has unique characteristics, and F. variegata Blume is usually used as traditional it grows mainly in tropical rainforest [1-3]. Secondary medicine for treatment of various illnesses, i.e., metabolite of the genus Ficus is rich in polyphenolic dysentery and ulceration. Our research group has been compounds, and flavonoids, therefore, the genus Ficus is reported the bioactivity of a secondary metabolite from usually used as traditional medicine for treatment of leaves, stem bark, and fruit of F. -

Aglaia Loheri Blanco

Journal of Medicinal Plants Research Vol. 4(1), pp. 58-63, 4 January, 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/jmpr DOI: 10.5897/JMPR09.400 ISSN 1996-0875© 2010 Academic Journals ` Full Length Research Paper Antimicrobial activity, cytotoxicity and phytochemical screening of Ficus septica Burm and Sterculia foetida L. leaf extracts Pierangeli G. Vital1, Rogelio N. Velasco Jr.1, Josemaria M. Demigillo1 and Windell L. Rivera1,2* 1Institute of Biology, College of Science, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines. 2Molecular Protozoology Laboratory, Natural Sciences Research Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City 1101, Philippines. Accepted 19 November, 2009 Ethanol extracts of leaves of Ficus septica Burm and Sterculia foetida L. were examined for their antibacterial, antifungal, antiprotozoal, and cytotoxic properties. To determine these activities, the extracts were tested against bacteria and fungus through disc diffusion assay; against protozoa through growth curve determination, antiprotozoal and cytotoxicity assays. The extracts revealed antibacterial activities, inhibiting the growth of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Antifungal assay for F. septica extract showed that it inhibited Candida albicans. The antiprotozoal assay against Trichomonas vaginalis showed that F. septica can reduce the number of parasites. Moreover, antiprotozoal assays against Entamoeba histolytica revealed that F. septica and S. foetida can inhibit the growth of the parasites, wherein the action can be comparable to metronidazole. With the in situ cell death detection kit, T. vaginalis exposed to F. septica and E. histolytica exposed to F. septica and S. foetida were observed to fluoresce in red surrounded by a yellow signal signifying apoptotic-like changes. -

Ctz78-02 (02) Lee Et Al.Indd 51 14 08 2009 13:12 52 Lee Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 78 (2) 51-64 (2009) Variation in the nocturnal foraging distribution of and resource use by endangered Ryukyu flying foxes(Pteropus dasymallus) on Iriomotejima Island, Japan Ya-Fu Lee1, 4, Tokushiro Takaso2, 5, Tzen-Yuh Chiang1, 6, Yen-Min Kuo1, 7, Nozomi Nakanishi2, 8, Hsy-Yu Tzeng3, 9, Keiko Yasuda2 1 Department of Life Sciences and Institute of Biodiversity, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 701, Taiwan 2 The Iriomote Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, 671 Iriomote, Takatomi-cho, Okinawa 907- 1542, Japan 3 Hengchun Research Center, Taiwan Forestry Research Institute, Pingtung 946, Taiwan 4 E-mail: [email protected] 5 E-mail: [email protected] 6 E-mail: [email protected] 7 E-mail: [email protected] 8 E-mail: [email protected] 9 E-mail: [email protected] Key words: abundance, bats, Chiroptera, diet, figs, frugivores, habitat Abstract Contents The nocturnal distribution and resource use by Ryukyu flying foxes Introduction ........................................................................................ 51 was studied along 28 transects, covering five types of habitats, on Material and methods ........................................................................ 53 Iriomote Island, Japan, from early June to late September, 2005. Study sites ..................................................................................... 53 Bats were mostly encountered solitarily (66.8%) or in pairs (16.8%), Bat and habitat census ................................................................ -

DNA Barcoding Confirms Polyphagy in a Generalist Moth, Homona Mermerodes (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

Molecular Ecology Notes (2007) 7, 549–557 doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01786.x BARCODINGBlackwell Publishing Ltd DNA barcoding confirms polyphagy in a generalist moth, Homona mermerodes (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) JIRI HULCR,* SCOTT E. MILLER,† GREGORY P. SETLIFF,‡ KAROLYN DARROW,† NATHANIEL D. MUELLER,§ PAUL D. N. HEBERT¶ and GEORGE D. WEIBLEN** *Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, 243 Natural Sciences Building, East Lansing, Michigan 48824, USA, †National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA, ‡Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, 1980 Folwell Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55108–1095 USA, §Saint Olaf College, 1500 Saint Olaf Avenue, Northfield, MN 55057, USA,¶Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G2W1, **Bell Museum of Natural History and Department of Plant Biology, University of Minnesota, 220 Biological Sciences Center, 1445 Gortner Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55108–1095, USA Abstract Recent DNA barcoding of generalist insect herbivores has revealed complexes of cryptic species within named species. We evaluated the species concept for a common generalist moth occurring in New Guinea and Australia, Homona mermerodes, in light of host plant records and mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I haplotype diversity. Genetic divergence among H. mermerodes moths feeding on different host tree species was much lower than among several Homona species. Genetic divergence between haplotypes from New Guinea and Australia was also less than interspecific divergence. Whereas molecular species identification methods may reveal cryptic species in some generalist herbivores, these same methods may confirm polyphagy when identical haplotypes are reared from multiple host plant families. A lectotype for the species is designated, and a summarized bibliography and illustrations including male genitalia are provided for the first time. -

The Philippine Flying Foxes, Acerodon Jubatus and Pteropus Vampyrus Lanensis

Journal of Mammalogy, 86(4):719- 728, 2005 DIETARY HABITS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATS: THE PHILIPPINE FLYING FOXES, ACERODON JUBATUS AND PTEROPUS VAMPYRUS LANENSIS Sam C. Stier* and Tammy L. M ildenstein College of Forestry and Conservation, University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59802, USA The endemic and endangered golden- crowned flying fox (Acerodon jubatus) coroosts with the much more common and widespread giant Philippine fmit bat (Pteropus vampyrus ianensis) in lowland dipterocarp forests throughout the Philippine Islands. The number of these mixed roost- colonies and the populations of flying foxes in them have declined dramatically in the last century. We used fecal analysis, interviews of bat hunters, and personal observations to describe the dietary habits of both bat species at one of the largest mixed roosts remaining, near Subic Bay, west- central Luzon. Dietary items were deemed “important” if used consistently on a seasonal basis or throughout the year, ubiquitously throughout the population, and if they were of clear nutritional value. Of the 771 droppings examined over a 2.5 -year period (1998-2000), seeds from Ficus were predominant in the droppings of both species and met these criteria, particularly hemiepiphytic species (41% of droppings of A. jubatus) and Ficus variegata (34% of droppings of P. v. ianensis and 22% of droppings of A. jubatus). Information from bat hunter interviews expanded our knowledge of the dietary habits of both bat species, and corroborated the fecal analyses and personal observations. Results from this study suggest that A. jubatus is a forest obligate, foraging on fruits and leaves from plant species restricted to lowland, mature natural forests, particularly using a small subset of hemiepiphytic and other Ficus species throughout the year.