University of Dundee Brand Building and Structural Change in the Scotch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9913 2004 Cover Outer

Diageo Annual Report 2004 Annual Report 2004 Diageo plc 8 Henrietta Place London W1G 0NB United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 20 7927 5200 Fax +44 (0) 20 7927 4600 www.diageo.com Registered in England No. 23307 Diageo is... © 2004 Diageo plc.All rights reserved. All brands mentioned in this Annual Report are trademarks and are registered and/or otherwise protected in accordance with applicable law. delivering results 165 Diageo Annual Report 2004 Contents Glossary of terms and US equivalents 1Highlights 63 Directors and senior management In this document the following words and expressions shall, unless the context otherwise requires, have the following meanings: 2Chairman’s statement 66 Directors’ remuneration report 3Chief executive’s review 77 Corporate governance report Term used in UK annual report US equivalent or definition Acquisition accounting Purchase accounting 5Five year information 83 Directors’ report Associates Entities accounted for under the equity method American Depositary Receipt (ADR) Receipt evidencing ownership of an ADS 10 Business description 84 Consolidated financial statements American Depositary Share (ADS) Registered negotiable security, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, representing four Diageo plc ordinary shares of 28101⁄108 pence each 10 – Overview 85 – Independent auditor’s report to Called up share capital Common stock 10 – Strategy the members of Diageo plc Capital allowances Tax depreciation 10 – Premium drinks 86 – Consolidated profit and loss account Capital redemption reserve Other additional capital -

No. 112 November 2011

No. 112 November 2011 THE RED HACKLE Raising to Distinction QueenVictoria School Admissions Deadline Sun 15 January 2012 Queen Victoria School in Dunblane is a co-educational boarding school for children of Armed Forces personnel who are Scottish, have served in Scotland or are part of a Scottish regiment. The QVS experience encourages and develops well-rounded, confident individuals in an environment of stability and continuity. The main entry point is into Primary 7 and all places are fully funded for tuition and boarding by the Ministry of Defence. Families are welcome to find out more by contacting Admissions on +44 (0) 131 310 2927 to arrange a visit. Queen Victoria School Dunblane Perthshire FK15 0JY www.qvs.org.uk No. 112 42nd 73rd November 2011 THE RED HACKLE The Chronicle of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment), its successor The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland, The Affiliated Regiments and The Black Watch Association Fifteen 2nd World War veterans representing all battalions of the Regiment gathered in Perth on 21 May 2011 to be honoured by the Association. NOVEMBER 2011 THE RED HACKLE 1 MUNRO & NOBLE SOLICITORS & ESTATE AGENTS Providing legal advice for over 100 years Proactively serving the Armed Forces: • Family Law • Executry & Wills • Estate Agency • House Sale & Purchase • Other legal Services • Financial Services phone Bruce on 01463 221727 Email: [email protected] www.munronoble.com Perth and Kinross is proud to be home to the Black Watch Museum and Home Headquarters Delivering Quality to the Heart of Scotland 2 THE RED HACKLE NOVEMBER 2011 THE Contents Editorial ..............................................................................................................................................3 RED HACKLE Regimental and Battalion News .......................................................................................................4 The Black Watch Heritage Appeal, The Regimental Museum and Friends of the Black Watch . -

The Impact of Multinational Investment on Alcohol Consumption Since The

The Impact of Multinational Investment on Alcohol ConsumptionSince the 1960s Teresada Silva LopesI Departmentof Economics, TheUniversity of Reading UniversidadeCatdlica Portuguesa Though much has been written about the alcohol beveragesindustry, lit- tle hasbeen said about its internationalisation.This articleattempts to analyse the impact of multinational enterprises(hereafter MNEs) on the availability and consumptionof alcohol in the world economyin the context of the evo- lution of the alcoholicbeverages industry since the beginningof the 1960s.2 It also givesspecial emphasis to the resourcesof the firm, and to the issuesof internationalrelated diversification and branding.For that purpose,it drawson businesshistory literature[Chandler, 1990;Jones and Morgan, 1994;Jones, 1996] and internationalbusiness theory. The studyis basedon the evolutionof the largestfive MNEs in the world in 1997,in terms of salesvolume - Allied Domecq, Bacardi-Martini,Diageo, Moat-HennessyLouis Vuitton and Seagram.These account for an increasingly large shareof the world trade in alcoholicbeverages. Because the aim of this article is to find a pattern of growth basedon comparativeanalysis of suc- cessfulfirms, rather than causalityrelations between growth and its determi- nants,the sampledoes not includeany 'control' firms, to which the behaviour of the successfulMNEs of alcoholicbeverages can be compared.It drawson evidencefrom the businessarchives of the MNEs, annualreports, interviews with top managers,other specialistsin the industry,and secondarydata. -

Wvb Dossier Report Lvmh Moet Hennessy - Louis Vuitton Se

WVB DOSSIER REPORT LVMH MOET HENNESSY - LOUIS VUITTON SE LVMH MOET HENNESSY - LOUIS VUITTON SE Generated On 22 Dec 2020 COMPANY PROFILE BUSINESS SALES BREAKDOWN WVB Number FRA000090103 Date 31-DEC-18 31-DEC-19 ISIN Number ARDEUT111929, FR0000121014, US5024412075 Currency EUR ('000) EUR ('000) Status ACTIVE [ PUBLIC ] FASHION AND LEATHER GOODS 18,455,000 22,237,000 SELECTIVE DISTRIBUTION 13,646,000 14,791,000 Country of Incorporation FRENCH REPUBLIC (FRANCE) PERFUMS AND COSMETICS 6,092,000 6,835,000 Industry Classification WINE,BRANDY & BRANDY SPIRITS (2084) WINE & SPIRITS 5,143,000 5,576,000 Address 22 AVENUE MONTAIGNE, PARIS, PARIS WATCHES & JEWELRY 4,123,000 4,405,000 Tel +33 144132222 OTHER AND HOLDINGS 714,000 1,214,000 Fax +33 144132223 ELIMINATIONS -1,347,000 -1,388,000 Website www.lvmh.fr Principal Activities The Company is a France-based luxury goods company. It owns a portfolio of luxury brands and GEOGRAPHIC SALES BREAKDOWN its business activities are divided into five segments: Wines and Spirits, Fashion and Leather Date 31-DEC-18 31-DEC-19 Goods, Perfumes and Cosmetics, Watches and Jewelry and Selective Retailing. Currency EUR ('000) EUR ('000) ASIE (HORS JAPON) 13,723,000 16,189,000 DIRECTORS/EXECUTIVES ÉTATS-UNIS 11,207,000 12,613,000 EUROPE (HORS FRANCE) 8,731,000 10,203,000 Chairman YVES-THIBAULT DE SILGUY AUTRES PAYS 5,323,000 6,062,000 Chairman BERNARD ARNAULT FRANCE 4,491,000 4,725,000 Chief Executive Officer BERNARD ARNAULT JAPON 3,351,000 3,878,000 Chief Financial Officer JEAN-JACQUES GUIONY Secretary MARC ANTOINE -

To Download a PDF of an Interview with Deirdre

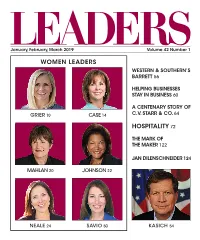

January, February, March 2019 Volume 42 Number 1 WOMEN LEADERS WESTERN & SOUTHERN’S BARRETT 56 HELPING BUSINESSES STAY IN BUSINESS 60 A CENTENARY STORY OF GRIER 10 CASE 14 C.V. STARR & CO. 64 HOSPITALITY 72 THE MARK OF THE MAKER 122 JAN DILENSCHNEIDER 124 MAHLAN 20 JOHNSON 22 NEALE 24 SAVIO 50 KASICH 54 Celebrating Life, Every Day, Everywhere An Interview with Deirdre Mahlan, President, Diageo North America EDITORS’ NOTE Deirdre Mahlan is Sometimes, this will require us We have been actively looking to encourage President of Diageo North America and is to innovate with new brands or that we women to continue their careers in the industry and responsible for the company’s largest acquire brands. Distil Ventures, our we engage our distributors and suppliers in that market in terms of sales and operating Diageo funded accelerator program same conversation. We are also working to ensure profit. In this role, she oversees Diageo’s for entrepreneurs sees us invest in the that our own supplier base is diverse. spirits and beer businesses in the U.S. and future of drinks, while allowing the It’s a journey and we have to continually keep Canada, which include brands such as businesses to grow independently. We our eye on the goal. We must continue to remove Johnnie Walker, Smirnoff, Crown Royal, also acquire brands, as we recently did the barriers so that everyone can progress, and we Ketel One, Captain Morgan, Baileys with Casamigos, where we saw a huge are making positive strides overall. and Guinness. Mahlan has more than opportunity. -

Scottish Industrial History Vol 20 2000

SCOTTISH INDUSTRIAL HISTORY Scotl21nd Business Archives Council of Scotland Scottish Charity Number SCO 02565 Volume20 The Business Archives Council of Scotland is grateful for the generous support given to this edition of Scottish Industrial History by United Distillers & Vintners SCOTTISH INDUSTRIAL HISTORY Volume20 B·A·C Scotl21nel Business Archives Council of Scotland Scorrish Choriry Number SCO 02565 Scottish Industrial History is published by the Business Archives Council of Scotland and covers all aspects of Scotland's industrial and commercial past on a local, regional and trans-national basis. Articles for future publication should be submitted to Simon Bennett, Honorary Editor, Scottish Industrial History, Archives & Business Records Centre, 77-87 Dumbarton Road, University of Glasgow Gll 6PE. Authors should apply for notes for contributors in the first instance. Back issues of Scottish Industrial History can be purchased and a list of titles of published articles can be obtained from the Honorary Editor or BACS web-site. Web-site: http://www.archives.gla.ac.uklbacs/default.html The views expressed in the journal are not necessarily those of the Business Archives Council of Scotland or those of the Honorary Editor. © 2000 Business Archives Council of Scotland and contributors. Cover illustrations Front: Advertisement Punch 1925- Johnnie Walker whisky [UDV archive] Back: Still room, Dalwhinnie Distillery 1904 [UDV archive] Printed by Universities Design & Print, University of Strathclyde 'Whisky Galore ' An Investigation of Our National Drink This edition is dedicated to the late Joan Auld, Archivist of the University of Dundee Scottish Industrial History Volume20 CONTENTS Page Scotch on the Records 8 Dr. R.B. -

1. Diageo Plc: the Road to Premiumisation

MASTER IN FINANCE MASTER’S FINAL WORK PROJECT EQUITY RESEARCH: DIAGEO PLC ANDRÉ MIGUEL BRITO DUARTE OCTOBER 2019 MASTER IN FINANCE MASTER’S FINAL WORK PROJECT EQUITY RESEARCH: DIAGEO PLC ANDRÉ MIGUEL BRITO DUARTE SUPERVISOR: PROFESSORA DOUTORA ANA ISABEL ORTEGA VENÂNCIO OCTOBER 2019 Acknowledgements Since this project represents the end of one of the most important stages of my life, I would like to express my sincere gratitude, to all the persons that had a relevant role along this journey. First, to Professor Ana Venâncio for the guidance, time and patience that had for me during the realization of this project. Second, to my parents and girlfriend, for making all this possible. And last but not least, to all my friends and colleagues for all the support and guidance given during this journey. 3 Index Abstract ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 Resumo ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 Index of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... 10 Index of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... 12 1. Diageo Plc: The road to premiumisation ................................................................................................ -

Reduce the Risk of a New Product Launch and Increase Brand Reputation

Reduce the risk of a new product launch and increase brand reputation Guinness tests the market for a new beer bottle design with overwhelming results During 2005, Guinness introduced a new perceptions about the company as being a design for its premium beer that included leader in its space. both major changes to the shape of the bottle As part of the “BLACK GOLD PROMOTION” as well as the labeling. In order to test this campaign, hostesses were located in the pubs new design with customers a promotional and customers were encouraged to comment campaign was planned to take place over a on the new design. Customers were given period of two weeks in approximately 50 pubs attractive cards that included the questions in Nigeria, the largest market for Guinness in and instructions for the survey. As an Africa. incentive, a cell phone recharge voucher was offered to customers that responded to the The “BLACK GOLD” Market survey. Research Campaign Over the years, Guinness has primarily used Campaign Response focus groups to identify customer needs and The total time to produce all materials, train determine how its products and brand are staff and launch the campaign took less than perceived in the market place. two weeks. After being introduced to the Touchwork EFM Over the three-week period of the campaign, solutions the forward looking Guinness more than 80% of all customers exposed to management team decided to use the solution the campaign provided a response to the as part of its promotional campaign. The survey. This exceptionally high response rate objective was to obtain quantitative customer is attributed to the fact that the in-pub feedback to validate the results obtained from promoters actively encouraged customers to focus groups. -

An Interview with Nick Blazquez, President, Africa, Diageo

23 An interview with Nick Blazquez, President, Africa, Diageo Diageo, the international drinks company, first shipped Guinness to Sierra Leone in 1827. It built its first brewery outside the British Isles in Nigeria in 1963. And in the latest fiscal year, 14 percent of Diageo’s global business—and 40 percent of its total growth—came from Africa. In this interview, McKinsey’s Martin Dewhurst talked with Nick Blazquez about the company’s growth strategies, the role of partnerships in its success, and how it attracts and develops people through a reliance on core values. Perspectives on global organizations 24 Martin Dewhurst McKinsey: Tell us a little about the scope of and Namibia Breweries to drive scale benefits your business in Africa and how you make of beer and spirits together. It was different in decisions about growth. Ethiopia. People knew we were bidding for the Meta Abo Brewery there, and a number of them Nick Blazquez: Within Africa we operate in asked whether they could partner with us. We 40 different countries. We tend to prioritize the couldn’t see what added value a partner would largest profit pools; the top 10 markets account bring at that stage, so it made sense from a value for about 80 percent of the profit pool. If you creation perspective that Diageo acquire that split those into beer and into spirits you’ve got asset 100 percent. 20 beverage alcohol categories. Five years ago, we were in 6 of those beer or spirits profit McKinsey: “Africa” can be a scary pools; now we’re in 16. -

Whiskey, Liquor, and Spirits

Guide to the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana Subject Categories: Whiskey, Liquor, and Spirits NMAH.AC.0060.S01.01.Whiskey Nicole Blechynden Funding for partial processing of the collection was supported by a grant from the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund (CCPF). 2016 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Brand Name Index........................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects .................................................................................................... 13 Container Listing ........................................................................................................... 15 Subseries : Business Records and Marketing Material, circa 1774-1964 (bulk 1850-1920)............................................................................................................. -

Insights, Challenges, & Solutions

READY-TO- DRINK AND PRE- MIXED COCKTAILS MARKET IN CHINA INSIGHTS, CHALLENGES, & SOLUTIONS CONTENTS Executive Summary PAGE3 Market Overview PAGE4 Common Challenges and Solutions PAGE7 Cases PAGE12 Conclusion PAGE17 In recent years, the global To succeed in the Greater China alcoholic ready-to-drink (RTDs) markets, businesses should: 1) EXECUTIVE and premixes market has shown understand the competition in the tremendous growth. There is a markets, 2) identify the best local surging demand for innovative markets to target, 3) develop the SUMMARY and high quality, but affordable right pricing strategy, 4) craft a beverages, and brands are eager successful branding strategy, and to meet the challenge. The Asia 5) find reliable local partners to Pacific region accounts for the achieve sales goals in the market. largest market share, where Westernization influences The experience of RIO and consumer behavior. Diageo demonstrates the value of investing in analyzing and In China, the demand is high understanding the market. Their among young consumers. success in China shows the The RTDs category delivers on return firms can enjoy when they convenience, as there is no need accurately assess the market and for preparations unlike mixed competition and employ the time alcoholic drinks. A local brand, and due diligence necessary to RIO, holds the biggest market develop strong relationships with share, but in recent years, many suitable local partners who can new players have been entering help them establish reliable sales the market. This is resulting in channels. increased sales and competition. 3 MARKET OVERVIEW 1% 1% China’s Pre-Mixed Cocktail 2% Industry 11% China’s pre-mixed cocktail market may be small, but it is predicted to grow rapidly. -

WNS Names Sir Anthony Greener to Board of Directors

WNS Names Sir Anthony Greener to Board of Directors June 19, 2007 MUMBAI, India & NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--June 19, 2007--WNS (Holdings) Limited (NYSE:WNS), a leading provider of offshore business process outsourcing (BPO) services, today announced the appointment of Sir Anthony Greener to its Board of Directors. Sir Anthony, 67, will replace Guy Sochovsky, who will retire from the Board effective July 24, 2007, and as a result, the majority of WNS' seven- member Board will be comprised of independent directors. "We are pleased to be able to successfully conclude another of the commitments that we made during our IPO," said Neeraj Bhargava, Group Chief Executive Officer. "Sir Anthony brings to WNS an extensive background, experience and leadership that will complement our existing Board strengths and will be a terrific asset to management as WNS continues to expand globally." Sir Anthony joins WNS after retiring from British Telecom plc (BT) in September 2006, where he served as Deputy Chairman of the Board. He was Chairman of Diageo plc through 2000, where he led the GBP 23 billion merger of Guinness plc and Grand Metropolitan plc, which was the largest merger ever in the UK at that time. As Chief Executive of Dunhill Holdings, Sir Anthony transformed that company from a small company focused on smoking-related businesses, into a significant international luxury products group. He has also served on the Boards of Robert Mondavi, French luxury goods and drinks group Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy (LVMH), Reed International, and Reed Elsevier, the Anglo-Dutch publishing company He currently serves as Chairman of the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority in the United Kingdom.