Trade Mark Inter-Partes Decision O/188/09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distillery Visitor Centre Information

Distillery Visitor Centre Information We are delighted to welcome back visitors to our Distillery Visitor Experiences across Scotland. Our number one priority is ensuring the safety and wellbeing of our staff, visitors and communities, which is why we’ve made a number of changes to our visitor experiences in line with Scottish Government guidelines. This document will give you the latest updates and information on how we’re making sure that our Distillery Visitor Experiences are a safe place for you. How we’re keeping you and our staff safe 38.2c Temperature checks Pre-bookings only on arrival All experiences must be pre-booked. 37.8c To ensure the safety of our visitors and staff, we will ask all guests to take a temperature check on arrival. 36.8c Reduced Physical Distancing store capacity All staff and visitors will be asked We’ll only allow a limited number of to maintain a physical distance guests in the shop at one time. throughout the distillery. One-way system Hand sanitiser stations This will be clearly marked throughout Installed at the entrance the experience. and in all common areas of the distillery. Extra cleaning We have introduced extra cleaning and Safe check out hygiene routines for your safety. Plastic barriers have been installed at all payment points and contactless payment is strongly advised. Frequently Asked Questions How do I book a tour? Please visit Malts.com to book a tour or email us (details below). Can you share with me your cancellation policy? If you booked online the cancellation policy will be visible on your booking and you will be refunded through the system. -

The 2019 Full Year Collectors and Investors Single Malt Scotch Review

THE 2019 FULL YEAR COLLECTORS AND INVESTORS SINGLE MALT SCOTCH REVIEW. RARE WHISKY 101 INVESTMENT GROWTH RETURNS TO THE RARE WHISKY MARKET. CONTENTS 3 Executive Summary Full Year 2019 9 Supply and Demand 12 Investment Comparison 16 Market Share by Volume – Top 10 Distilleries League Table 20 Market Share by Value – Top 10 Distilleries League Table 23 Rare Whisky Collectors Ranking – League Table 25 Rare Whisky Investors Ranking – League Table 27 Grain in Granularity 35 Crystal Ball Gazing – What Next? RW101 | FULL YEAR REVIEW 2019 2 FULL YEAR 2019 Executive SUMMARY RW101 | FULL YEAR REVIEW 2019 3 SPRINGBANK RETAINED ITS HALF YEAR NUMBER ONE POSITION IN THE INVESTOR RANKINGS, CLOSELY FOLLOWED BY SILENT DISTILLERIES ROSEBANK AND BRORA. POUND FOR POUND, MACALLAN NOW ACCOUNTS FOR ALMOST 40% OF MARKET. RW101 | FULL YEAR REVIEW 2019 4 VOLUME AND VALUE ANALYSIS VOLUME VALUE £ 160,000 £70,000,000 140,000 £60,000,000 143,895 120,000 £50,000,000 100,000 £57,707,707 £40,000,000 107,890 80,000 £30,000,000 83,713 60,000 £40,772,550 £20,000,000 40,000 58,758 £14,211,767 £9,562,405 43,458 £10,000,000 £25,060,058 20,000 0 £0 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 The number of recorded bottles of Single Malt The recorded £ value of collectable bottles of Scotch Whisky sold at auction in the UK in FY Single Malt Scotch Whisky sold at auction in the 2019 increased by 33.37% to 143,895 (107,890 UK in FY 2019 rose by 41.54% to a record high of were sold in FY 2018). -

Boisdale of Bishopsgate Whisky Bible

BOISDALE Boisdale of Bishopsgate Whisky Bible 1 All spirits are sold in measures of 25ml or multiples thereof. All prices listed are for a large measure of 50ml. Should you require a 25ml measure, please ask. All whiskies are subject to availability. 1. Springbank 10yr 19. Old Pulteney 17yr 37. Ardbeg Corryvreckan 55. Glenfiddich 21yr 2. Highland Park 12yr 20. Glendronach 12yr 38. Ardbeg 10yr 56. Glenfiddich 18yr 3. Bowmore 12yr 21. Whyte & Mackay 30yr 39. Lagavulin 16yr 57. Glenfiddich 15yr Solera 4. Oban 14yr 22. Royal Lochnagar 12yr 40. Laphroaig Quarter Cask 58. Glenfarclas 10yr 5. Balvenie 21yr PortWood 23. Talisker 10yr 41. Laphroaig 10yr 59. Macallan 18yr 6. Glenmorangie Signet 24. Springbank 15yr 42. Ardbeg Uigeadail 60. Highland Park 18yr 7. Suntory Yamazaki DR 25. Ailsa Bay 43. Tomintoul 16yr 61. Glenfarclas 25yr 8. Cragganmore 12yr 26. Caol Ila 12yr 44. Glenesk 1984 62. Macallan 10yr Sherry Oak 9. Brora 30yr 27. Port Charlotte 2008 45. Glenmorangie 25yr QC 63. Glendronach 12yr 10. Clynelish 14yr 28. Balvenie 15yr 46. Strathmill 12yr 64. Balvenie 12yr DoubleWood 11. Isle of Jura 10yr 29. Glenmorangie 18yr 47. Glenlivet 21yr 65. Aberlour 18yr 12. Tobermory 10yr 30. Macallan 12yr Sherry Cask 48. Macallan 12yr Fine Oak 66. Auchentoshan 3 Wood 13. Glenfiddich 26yr Excellence 31. Bruichladdie Classic Laddie 49. Glenfiddich 12yr 67. Dalmore King Alexander III 14. Dalwhinnie 15yr 32. Chivas Regal 18yr 50. Monkey Shoulder 68. Auchentoshan 12yr 15. Glenmorangie Original 33. Chivas Regal 25yr 51. Glenlivet 25yr 69. Benrinnes 23yr 2 16. Bunnahabhain 12yr 34. Dalmore Cigar Malt 52. Glenlivet 12yr 70. -

9913 2004 Cover Outer

Diageo Annual Report 2004 Annual Report 2004 Diageo plc 8 Henrietta Place London W1G 0NB United Kingdom Tel +44 (0) 20 7927 5200 Fax +44 (0) 20 7927 4600 www.diageo.com Registered in England No. 23307 Diageo is... © 2004 Diageo plc.All rights reserved. All brands mentioned in this Annual Report are trademarks and are registered and/or otherwise protected in accordance with applicable law. delivering results 165 Diageo Annual Report 2004 Contents Glossary of terms and US equivalents 1Highlights 63 Directors and senior management In this document the following words and expressions shall, unless the context otherwise requires, have the following meanings: 2Chairman’s statement 66 Directors’ remuneration report 3Chief executive’s review 77 Corporate governance report Term used in UK annual report US equivalent or definition Acquisition accounting Purchase accounting 5Five year information 83 Directors’ report Associates Entities accounted for under the equity method American Depositary Receipt (ADR) Receipt evidencing ownership of an ADS 10 Business description 84 Consolidated financial statements American Depositary Share (ADS) Registered negotiable security, listed on the New York Stock Exchange, representing four Diageo plc ordinary shares of 28101⁄108 pence each 10 – Overview 85 – Independent auditor’s report to Called up share capital Common stock 10 – Strategy the members of Diageo plc Capital allowances Tax depreciation 10 – Premium drinks 86 – Consolidated profit and loss account Capital redemption reserve Other additional capital -

The Whisky Sale

THE WHISKY SALE Wednesday 6 June 2018 Edinburgh THE WHISKY SALE | Edinburgh | Wednesday 6 June 2018 | Edinburgh Wednesday 24753 THE WHISKY SALE Wednesday 6 June 2018 at 11am 22 Queen Street, Edinburgh VIEWING ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES IMPORTANT INFORMATION Tuesday 5 June Martin Green Monday to Friday 8.30am The United States Government 10am to 4pm +44 (0) 7775 842 626 to 6.00pm has banned the import of ivory Wednesday 6 June +44 (0) 131 225 2266 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 into the USA. Lots containing 9am to 11am [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder ivory are indicated by the information including after-sale symbol Ф printed beside the SALE NUMBER Press Enquiries: collection and shipment lot number in this catalogue. 24753 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5871 ILLUSTRATIONS CATALOGUE Front cover: Lots 52 Back cover: Lot 146 £10.00 Inside front cover: Lot 16 BIDS Inside back cover: Lot 75 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax [email protected] Please note that bids should be submitted no later than 4pm on the day prior to the sale. New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting bids. Failure to do this may result in your bid not being processed. Bidding by telephone will only be accepted on a lot with the lower estimate of £500. Live online bidding is available for this sale Please email [email protected] with ‘live bidding’ in the subject line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. -

Samaroli Catalogue 2020 Web-Eng

1 NON O R T H N O RTH A T L A N TIC S E A O C E A N ¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ ¤ § ¢ ¢ Island ¤ ¡ Highland ¦ ¦ Speyside Campbeltown Islay - Lowland ¤ ¥ ¦ 2 … § … § ¨ © § … § § … ¤ § ª … … ¤ ¡ … 3 SAMAROLI ISLAY 2 BLENDED MALT SCOTCH WHISKY BOTTLED IN SCOTLAND IN 2020 3 3 Our eye or rather our nose has stopped meat come to the nose with Shy, a bit ' like on a lile boy who allows us to bole the scents of a fireplace turned off aer the another edition of our philosophy of -

Cooling Tower Register

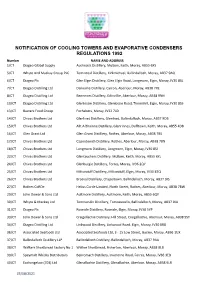

NOTIFICATION OF COOLING TOWERS AND EVAPORATIVE CONDENSERS REGULATIONS 1992 Number NAME AND ADDRESS 1/CTDiageo Global Supply Auchroisk Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6XS 5/CTWhyte And Mackay Group PLC Tomintoul Distillery, Kirkmichael, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9AQ 6/CTDiageo Plc Glen Elgin Distillery, Glen Elgin Road, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SL 7/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Dailuaine Distillery, Carron, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7RE 8/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Benrinnes Distillery, Edinvillie, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 9NN 10/CTDiageo Distilling Ltd Glenlossie Distillery, Glenlossie Road, Thomshill, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SS 13/CTBaxters Food Group Fochabers, Moray, IV32 7LD 14/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenlivet Distillery, Glenlivet, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9DB 15/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Allt A Bhainne Distillery, Glenrinnes, Dufftown, Keith, Moray, AB55 4DB 16/CTGlen Grant Ltd Glen Grant Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BS 17/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Caperdonich Distillery, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BN 18/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Longmorn Distillery, Longmorn, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8SJ 22/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glentauchers Distillery, Mulben, Keith, Moray, AB55 6YL 24/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Glenburgie Distillery, Forres, Moray, IV36 2QY 25/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Miltonduff Distillery, Miltonduff, Elgin, Moray, IV30 8TQ 26/CTChivas Brothers Ltd Braeval Distillery, Chapeltown, Ballindalloch, Moray, AB37 9JS 27/CTRothes CoRDe Helius Corde Limited, North Street, Rothes, Aberlour, Moray, AB38 7BW 29/CTJohn Dewar & Sons Ltd Aultmore Distillery, -

![TDH Whisky Menu[4]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7897/tdh-whisky-menu-4-277897.webp)

TDH Whisky Menu[4]

W h e r e y o u n o w s t a n d ...THE UNWIN STORES... — Est. 1843 — ...was once a... BOARDING HOUSE opium dealer bootmaker — Est. 1924— a Dr. IN E R O C H K T S Recapturing the convivial spirit of Sydney’s formative years, The Doss House unites fne spirits & cocktails with the historical charm of one of the city’s oldest suburbs, The Rocks. Built in the 1840s, this space has been the home to a rich, eclectic collection of tenants including a bootmaker, boarding house, doctor’s surgery & opium dealer, some which have been entwined within the interiors of the fve, cosy bar spaces. Te result is a bar steeped in character, ambiance & history. Welcome to T h e D o s s H o u s e . © Whiskey Flights WORLD OF WHISKY —35— Suntory Chita Grain Malt 43% Japan Aged in a combination of wine, sherry and bourbon casks. This is a light whisky with subtle notes of mint, honey and wood spice. Bushmills 10 Year Old 40 % Ireland A former winner of Best Irish Single Malt Whiskey in the World at the World Whiskies Awards, this has a far greater depth of flavour than standard Irish blends. Sweet honey, vanilla and milk chocolate aroma. Jim Beam Bonded 50% America Vibrant but bold, with soft creamy body. Notes of cherries, coconut, toasted almond and tobacco. Starward Wine Cask Malt 41% Australia Matured in Barossa ex-shiraz casks for only a few years in 100 and 200 litre casks which give notes of vanilla, prunes and plums with a pleasant fruity chocolate spice on the finish. -

To See Our Tasting Tray Menu

Highlander Inn – Craigellachie Whisky tasting menus 06/07/2016 Highlander Inn – Craigellachie Whisky tasting menus 1. The Speyside Malt Whisky Trail ~ Official Bottlings £23.90 Balvenie Doublewood 12yo 40.0% Cardhu 12yo 40.0% Glenfiddich 12yo 40.0% Strathisla 12yo 43.0% Glenlivet 18yo 43.0% Benromach Organic 43.0% 2. Highlands & Islands ~ Official Bottlings £24.40 Dalwhinnie 15yo 43.0% Glenmorangie 10yo 40.0% Isle of Jura Superstition 45.0% Clynelish 14yo 46.0% Highland Park 12yo 40.0% Oban 14yo 43.0% 3. Diageo’s “Classic Malts” £24.80 Glenkinchie Lowlands 12yo 43.0% Dalwhinnie Highlands 15yo 43.0% Cragganmore Speyside 12yo 40.0% Oban Highlands 14yo 43.0% Talisker Islands 10yo 45.8% Lagavulin Islay 16yo 43.0% 4. A brief journey around Scotland ~ Official Bottlings £23.90 Auchentoshan Lowlands 43.0% Dalwhinnie Highlands 15yo 43.0% Aberlour Speyside 10yo 40.0% Highland Park Islands 12yo 40.0% Springbank Campbeltown 10yo 46.0% Bowmore Islay 12yo 40.0% 5. Age Comparison ~ Official Bottlings £34.00 Glenlivet Speyside 12yo 43.0% Glenlivet Speyside 18yo 43.0% Highland Park Islands 12yo 40.0% Highland Park Islands 18yo 43.0% Glendronach East Highlands 12yo 40.0% Glendronach East Highlands 18yo 46.0% 6. Islay Malts ~ Official Bottlings £30.70 Bowmore 12yo 40.0% Kilchoman 100% Islay 50.0% Laphroaig Quarter cask 48.0% Ardbeg 10yo 46.0% Lagavulin Distillers Edition, Pedro Ximenez Finish 16yo 43.0% Caol Ila ` 12yo 43.0% 06/07/2016 Highlander Inn – Craigellachie Whisky tasting menus 7. Lesser Known Speyside Selections from the “Flora & Fauna” range £35.80 Glenlossie 10yo 43.0% Strathmill 12yo 43.0% Auchroisk 10yo 43.0% Benrinnes 15yo 43.0% Mortlach 16yo 43.0% Dailuaine 16yo 43.0% 8. -

Speyside the Land of Whisky

The Land of Whisky A visitor guide to one of Scotland’s five whisky regions. Speyside Whisky The practice of distilling whisky No two are the same; each has has been lovingly perfected its own proud heritage, unique throughout Scotland for centuries setting and its own way of doing and began as a way of turning things that has evolved and been rain-soaked barley into a drinkable refined over time. Paying a visit to spirit, using the fresh water from a distillery lets you discover more Scotland’s crystal-clear springs, about the environment and the streams and burns. people who shape the taste of the Scotch whisky you enjoy. So, when To this day, distilleries across the you’re sitting back and relaxing country continue the tradition of with a dram of our most famous using pure spring water from the export at the end of your distillery same sources that have been tour, you’ll be appreciating the used for centuries. essence of Scotland as it swirls in your glass. From the source of the water and the shape of the still to the Home to the greatest wood of the cask used to mature concentration of distilleries in the the spirit, there are many factors world, Scotland is divided into five that make Scotch whisky so distinct whisky regions. These are wonderfully different and varied Highland, Lowland, Speyside, Islay from distillery to distillery. and Campbeltown. Find out more information about whisky, how it’s made, what foods to pair it with and more: www.visitscotland.com/whisky For more information on travelling in Scotland: www.visitscotland.com/travel Search and book accommodation: www.visitscotland.com/accommodation 05 15 03 06 Speyside 07 04 08 16 01 Speyside is home to some of Speyside you’re never far from a 10 Scotland’s most beautiful scenery distillery or two. -

Whiskiesl I WHISKY N L V L E Y R G a R R AY a REVIEW

H FY C N SCOTCH O E whiskiesL I WHISKY N L V L E Y R G A R R AY A REVIEW EDITION 4 AUTUMN 1995 TRUMPET FOR TWO “An excellent mail order business” is the accolade awarded us in a recent Decanter magazine article. This sort of comment is something that has to be earned and we are proud to have done so. Because of our hands-on approach it is easier for us to look after you, the customer, on a personal basis. As a private partnership we are depend- ent on the shop in Inveraray and our mail order business and so we are very careful about our quality of service and the suggestions and recommendations we make. This edition of the SWR is twelve pages, the additional four pages being occupied by our ‘glossy’ catalogue, full of desir- able products for you to buy and enjoy. All of the items featured come with our recommendation and should you wish to return anything to us because you are disappointed, no problems. TAX CAMPAIGN RESULTS AWAITED We also give news of the appointment of Visitors to our shop, distilleries and the recent round of Party conferences have our house malt, The Inverarity. We had the opportunity to sign this card appealing to the Government to reduce the weren’t looking for a house malt but punitive tax on Scotch Whisky. How effective the campaign has been will be known found this so worthy of frequent recom- at the end of November when the Chancellor gets up on his back legs for the Budget. -

No. 112 November 2011

No. 112 November 2011 THE RED HACKLE Raising to Distinction QueenVictoria School Admissions Deadline Sun 15 January 2012 Queen Victoria School in Dunblane is a co-educational boarding school for children of Armed Forces personnel who are Scottish, have served in Scotland or are part of a Scottish regiment. The QVS experience encourages and develops well-rounded, confident individuals in an environment of stability and continuity. The main entry point is into Primary 7 and all places are fully funded for tuition and boarding by the Ministry of Defence. Families are welcome to find out more by contacting Admissions on +44 (0) 131 310 2927 to arrange a visit. Queen Victoria School Dunblane Perthshire FK15 0JY www.qvs.org.uk No. 112 42nd 73rd November 2011 THE RED HACKLE The Chronicle of The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment), its successor The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion The Royal Regiment of Scotland, The Affiliated Regiments and The Black Watch Association Fifteen 2nd World War veterans representing all battalions of the Regiment gathered in Perth on 21 May 2011 to be honoured by the Association. NOVEMBER 2011 THE RED HACKLE 1 MUNRO & NOBLE SOLICITORS & ESTATE AGENTS Providing legal advice for over 100 years Proactively serving the Armed Forces: • Family Law • Executry & Wills • Estate Agency • House Sale & Purchase • Other legal Services • Financial Services phone Bruce on 01463 221727 Email: [email protected] www.munronoble.com Perth and Kinross is proud to be home to the Black Watch Museum and Home Headquarters Delivering Quality to the Heart of Scotland 2 THE RED HACKLE NOVEMBER 2011 THE Contents Editorial ..............................................................................................................................................3 RED HACKLE Regimental and Battalion News .......................................................................................................4 The Black Watch Heritage Appeal, The Regimental Museum and Friends of the Black Watch .