Playing the Binding of Isaac Video Game Through the Reception History of the Aqedah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected]

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Fall 12-2016 The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes Christiane Shaker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Shaker, Christiane, "The "Lamb of God" Title in John's Gospel: Background, Exegesis, and Major Themes" (2016). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2220. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2220 Seton Hall University THE “LAMB OF GOD” TITLE IN JOHN’S GOSPEL: BACKGROUND, EXEGESIS, AND MAJOR THEMES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEOLOGY CONCENTRATION IN BIBLICAL THEOLOGY BY CHRISTIANE SHAKER South Orange, New Jersey October 2016 ©2016 Christiane Shaker Abstract This study focuses on the testimony of John the Baptist—“Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” [ἴδε ὁ ἀµνὸς τοῦ θεοῦ ὁ αἴρων τὴν ἁµαρτίαν τοῦ κόσµου] (John 1:29, 36)—and its impact on the narrative of the Fourth Gospel. The goal is to provide a deeper understanding of this rich image and its influence on the Gospel. In an attempt to do so, three areas of concentration are explored. First, the most common and accepted views of the background of the “Lamb of God” title in first century Judaism and Christianity are reviewed. -

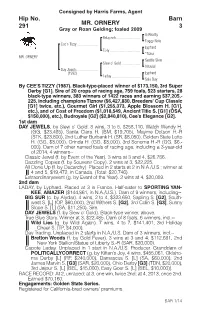

MR. ORNERY Barn 3 Hip No

Consigned by Harris Farms, Agent Hip No. Barn 291 MR. ORNERY 3 Gray or Roan Gelding; foaled 2009 In Reality Relaunch........................... Foggy Note Cee's Tizzy........................ Lyphard Tizly .................................. *Tizna MR. ORNERY Seattle Slew Slew o' Gold ..................... Alluvial Day Jewels........................ (1992) Lyphard Laday................................ Sale Day By CEE'S TIZZY (1987). Black-type-placed winner of $173,150, 3rd Super Derby [G1]. Sire of 20 crops of racing age, 759 foals, 523 starters, 28 black-type winners, 383 winners of 1422 races and earning $37,205,- 225, including champions Tiznow ($6,427,830, Breeders' Cup Classic [G1] twice, etc.), Gourmet Girl ($1,255,373, Apple Blossom H. [G1], etc.), and of Cost of Freedom ($1,018,549, Ancient Title S. [G1] (OSA, $150,000), etc.), Budroyale [G2] ($2,840,810), Cee’s Elegance [G2]. 1st dam DAY JEWELS, by Slew o' Gold. 8 wins, 3 to 5, $258,110, Watch Wendy H. (GG, $23,485), Santa Clara H. (BM, $19,705), Mayme Dotson H.-R (STK, $23,800), 2nd Luther Burbank H. (SR, $8,050), Golden State Lotto H. (GG, $8,000), Orinda H. (GG, $8,000), 3rd Sonoma H.-R (GG, $6,- 000). Dam of 7 other named foals of racing age, including a 3-year-old of 2014, 4 winners-- Classic Jewel (f. by Event of the Year). 3 wins at 3 and 4, $26,786. Dazzling Copies (f. by Souvenir Copy). 2 wins at 3, $22,225. All Done Up (f. by Decarchy). Placed in 2 starts at 2 in N.A./U.S.; winner at 4 and 5, $19,472, in Canada. -

GOD's GREATEST SIN Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1

GOD’S GREATEST SIN Rosh Hashanah Second Day October 1, 2019 2 Tishri 5780 Rabbi Jennifer R. Greenspan I have found, at least in my life, that we are often our own worst critics. We expect too much of ourselves, and we overuse the word “should,” trying desperately to reach some unattainable goal of perfection. I should be able to work a full-time job, maintain a clean home, cook and serve three healthy meals a day, and find at least an hour a day for exercise. I should be able to find time to meditate, go to bed earlier, get up earlier, still get eight hours of sleep, drink more water, and start a yoga routine. I should stop buying things I don’t need and be better about saving money. I should stop using disposable bottles, plastic straws, and eating anything that isn’t organic. I should come to synagogue more often. I should stop looking at my phone. I should use my phone to make sure I’m on top of my calendar. I should spend more time with my family. I should figure out how to be perfect already. How many of those “should”s that we constantly tell ourselves are really true to who we are, and how many come from a culture of perfectionism? When we are sitting in a season of judgement, how are we to judge ourselves and our deeds and our sins when we know we’re not perfect? In the Talmud, Rabbi Abbahu asks: Why on Rosh Hashanah do we sound a shofar made from a ram’s horn? אמר הקדוש ברוך הוא: תקעו לפני בשופר של איל כדי שאזכור לכם עקידת יצחק The Holy Blessed One said: use a shofar made from a ram’s horn, so that I will be reminded of the -

The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murder and Kabbalah: Seeds Of

Studies in Christian-Jewish Relations Volume 4 (2009): Jospe R 1-4 REVIEW Lippman Bodoff The Binding of Isaac, Religious Murder and Kabbalah: Seeds of Jewish Extremism and Alienation? (Jerusalem and New York: Devora Publishing, 2005) Reviewed by Raphael Jospe, Bar Ilan University Twice every year, on Rosh Ha-Shanah and on the Sabbath, a few weeks later, when Genesis 22 is read as part of the annual cycle of reading the Torah in the synagogue, Jews are confronted by the drama of the Akedah, Abraham’s “binding” of Isaac in an ultimately aborted attempt to offer his beloved son as a sacrifice to God. On many Sabbaths, and on festivals when the Yizkor (memorial) prayers are recited, Ashkenazi Jews have the custom of reciting the Av Ha-Rahamim, an anonymous prayer from the thirteenth century commemorating Jewish communities martyred in Germany during the first Crusade. Masada, where, after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple, some 960 Jewish zealots and their families held off the Roman army and finally, facing the inevitable, committed mass suicide in 73 CE rather than surrender, is not merely a spectacular historical and archeological site; it has become a site of pilgrimage, where Israeli soldiers proclaim “Masada shall not fall again,” and where many youngsters celebrate their becoming Bar/Bat Mitzvah. The common thread to these three Jewish practices is what Lippman Bodoff calls “religious murder.” To offer one’s child as a sacrifice to God is murder. To kill one’s family and then commit suicide, even under extreme circumstances, as Jewish husbands and fathers did at Masada, and then a thousand years later in the face of Crusader mobs in the Rhineland (1096), and again a century later in York, England, on the Sabbath before Passover, 1190, is, Bodoff argues passionately, murder, and a violation of the moral teachings of Judaism. -

Reading the Old Testament History Again... and Again

Reading the Old Testament History Again... and Again 2011 Ryan Center Conference Taylor Worley, PhD Assistant Professor of Christian Thought & Tradition 1 Why re-read OT history? 2 Why re-read OT history? There’s so much more to discover there. It’s the key to reading the New Testament better. There’s transformation to pursue. 3 In both the domains of nature and faith, you will find the most excellent things are the deepest hidden. Erasmus, The Sages, 1515 4 “Then he said to them, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.’” Luke 24:44 5 God wishes to move the will rather than the mind. Perfect clarity would help the mind and harm the will. Humble their pride. Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 1669 6 Familiar Approaches: Humanize the story to moralize the characters. Analyze the story to principalize the result. Allegorize the story to abstract its meaning. 7 Genesis 22: A Case Study 8 After these things God tested Abraham and said to him, “Abraham!” And he said, “Here am I.” 2 He said, “Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains of which I shall tell you.” “By myself I have sworn, declares the Lord, because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your only son, 17 I will surely bless you, and I will surely multiply your offspring as the stars of heaven and as the sand that is on the seashore. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

God, Abraham, and the Abuse of Isaac

Word & World Volume XV, Number 1 Winter 1995 God, Abraham, and the Abuse of Isaac TERENCE E. FRETHEIM Luther Seminary St. Paul, Minnesota HIS IS A CLASSIC TEXT.1 IT HAS CAPTIVATED THE IMAGINATION OF MANY INTER- Tpreters, drawn both by its literary artistry and its religious depths. This is also a problem text. It has occasioned deep concern in this time when the abuse of chil- dren has screamed its way into the modern consciousness: Is God (and by virtue of his response, Abraham) guilty of child abuse in this text? There is no escaping the question, and it raises the issue as to the continuing value of this text. I. MODERN READINGS Psychoanalyst Alice Miller claims2 that Genesis 22 may have contributed to an atmosphere that makes it possible to justify the abuse of children. She grounds her reflections on some thirty artistic representations of this story. In two of Rem- brandt’s paintings, for example, Abraham faces the heavens rather than Isaac, as if in blind obedience to God and oblivious to what he is about to do to his son. His hands cover Isaac’s face, preventing him from seeing or crying out. Not only is Isaac silenced, she says (not actually true), one sees only his torso; his personal fea- tures are obscured. Isaac “has been turned into an object. He has been dehuman- ized by being made a sacrifice; he no longer has a right to ask questions and will 1This article is a reworking of sections of my commentary on Genesis 22 in the New Interpreters Bi- ble (Nashville: Abingdon, 1994) 494-501. -

Bibliotheca Sacra and Theological Review

1868.] THE LAND OF MORIAH. 760 ARTICLE V. THE LAND OF MORIAH. BY DV. SAlIUEL WOLCOTT, D.D., CLEVELAND, OHIO. A QUESTION has been raised witbin a. few years respecting tbe locality designated in the divine direction to Abraham to offer his son Isaac in sacrifice. The command was: "Take now tby son, thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest, and get thee iuto the land of,Moriah, and offer bim there for a burnt offering upon one of the mountains which I will tell thee of" (Gen. xxii. 2). The name Moriah QCcurs but in one more passage in the sacred scriptures, and in this it is given as the site of the temple which Solomon built: "Then Solomon began to build tbe bouse of the Lord at Jerusalem, in mount :Moriab, where the Lord appeared unto David his father, in the place that David bad prepared in the threshiug-Hoor of Orna.n the Jcbusite" (2 ebron. iii. 1). Is the Mount Moriah in Jerusalem on which the temple stood identical with one of the mountains in the land of lIeriuh on which Abraham was directed to offer Isaac? Such has boon tbo accepted tradition and current belief. The identity, naturally suggested by the name, does not appear to bave been seriously questioned, except by the Sa.ma.ritaus in behalf of Mount Gerizim, which has been rejected by others as the unfounded cla.im of an interested party. This discredited claim found, at length, a champion in Professor Stanley, who in his " Sinai and Palestino" gav!! his reasons for adopting it, and in his later" Lectures on Jewish History," ventured to assume it as an ascertained and estab lisI1ed site. -

Religion, Video Games, and Simulated Worlds

Workshop and Lectures Religion, Video Games, and Simulated Worlds Trento | 5-6.02.2018 Fly-8 / 1-2018_ISR Programme Monday, 5th February OPEN WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) 15.00 - 15.30 Religion & Innovation: Our Mission and the Workshop Series Marco Ventura, Fondazione Bruno Kessler 15.30 - 16.30 Institution of Belief: Religio and Faith in Simulated Worlds Vincenzo Idone Cassone, University of Turin Mattia Thibault, University of Turin 16.30 - 17.00 Break PUBLIC LECTURE (Aula grande) 17.00 - 19.00 Gamevironments as a Communicative Figuration. An Introduction to a Heuristic Concept for Analyzing Religion and Video Gaming Kerstin Radde-Antweiler, University of Bremen 19.30 Dinner Tuesday, 6th February OPEN WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) 09.00 - 10.30 God, Karma & Video Games: An Evolving Relationship Marco Mazzaglia, Synesthesia and MixedBag, Turin 10.30 - 11.00 Break CLOSED WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) FBK researchers and invited speakers only 11.00 - 13.00 Exploration of Project Ideas and Funding Schemes 13.00 - 14.15 Lunch Buffet OPEN WORKSHOP (Aula Piccola) 14.15 - 15.00 Virtualising Religious Objects Paul Chippendale, Fondazione Bruno Kessler, ICT-TeV Fabio Poiesi, Fondazione Bruno Kessler, ICT-TeV 15.00 - 16.15 Religion as Game Mechanic Tobias Knoll (University of Heidelberg) 16.15 - 17.00 Break PUBLIC LECTURE (Aula grande) 17.00 – 19.00 In principio erano i bit: genesi e fede dei mondi videoludici Vincenzo Idone Cassone, University of Turin Mattia Thibault, University of Turin 19.30 Dinner Short Bios PAUL IAN CHIPPENDALE has a PhD in Telecommunication and a degree in Information Technology from Lancaster University (UK). He is currently a Senior Researcher in the ICT Centre of Fondazione Bruno Kessler. -

Priming and Negative Priming in Violent Video Games

Priming and Negative Priming in Violent Video Games David Zendle Doctor of Philosophy University of York Computer Science September 2016 Abstract This is a thesis about priming and negative priming in video games. In this context, priming refers to an effect in which processing some concept makes reactions to related concepts easier. Conversely, negative priming refers to an effect in which ignoring some concept makes reactions to related concepts more difficult. The General Aggression Model (GAM) asserts that the depiction of aggression in VVGs leads to the priming of aggression-related concepts. Numerous studies in the literature have seemingly confirmed that this relationship exists. However, recent research has suggested that these results may be the product of confounding. Experiments in the VVG literature commonly use different commercial off- the-shelf video games as different experimental conditions. Uncontrolled variation in gameplay between these games may lead to the observed priming effects, rather than the presence of aggression-related content. Additionally, in contrast to the idea that players of VVGs necessarily process in-game concepts, some theorists have suggested that players instead ignore in-game concepts. This suggests that negative priming rather than priming might happen in VVGs. The first series of experiments reported in this thesis show that priming does not happen in video games when known confounds are controlled. These results also suggest that negative priming may occur in these cases. However, the games used in these experiments were not as realistic as many VVGs currently on the market. This raises concerns that these results may not generalise widely. I therefore ran a further three experiments. -

Dvar Torah - Lech Lecha

Dvar Torah - Lech Lecha Did you know that Sheva Brachot are in the Paraha of Lech Lecha? Immediately after Hashem commands Avram and Sarai to uproot them- selves from the land of Mesopotamia in order to make Aliyah ‘el ha’aretz asher areka’ – to the land which Hashem will show them. Hashem follows up by giving seven blessings to Avram; ‘Ve’escha L’goi gadol’ - and I will make you into a great nation, ‘v’avarechecha’ - and I will bless you, ‘Veagadla Shemecha’ - and I will make your name great, ‘v’heye bracha’ - and you will be a blessing, ‘V’avarcha mevarachecha’ - I will bless those who bless you, ‘umcallecha a’or’ - and I will curse those who curse you. And the seventh blessing is ‘v’nivrechu vecha kol mishpachot ha’adama’ - and may every family on earth be blessed thanks to the impact you will have on them. Such wonderful blessings! And actually these seven blessings match the sentiments that accompany our good wishes to every bride and groom for whom we recite ‘sheva brachot’ under the ‘chupa’ and during the first seven days of their marriage. We want them to be blessed by Hashem, we want them to have a positive impact on their surroundings. We want Hashem to be with them always and to prevent others from standing in the way of their success. There is a further strong comparison. You see the term ‘lech lecha’ appears twice in the bible, once in our parsha of Lech Lecha and the second, fascinat- ingly, in a weeks’ time, when we will read in Parashat Va’eira, ‘v’lech lecha el eretz hamoria’ - uproot yourself, make an Aliyah, to the land of Moriah and that’s where the akeida (the binding of Isaac) took place. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry.