Acta 115.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Testing of the Torsional Stiffness of the Passenger Car Frame and Its Validation by Means of Finite Element Analysis

The Archives of Automotive Engineering – Archiwum Motoryzacji Vol. 85, No. 3, 2019 83 TESTING OF THE TORSIONAL STIFFNESS OF THE PASSENGER CAR FRAME AND ITS VALIDATION BY MEANS OF FINITE ELEMENT ANALYSIS KRZYSZTOF PODKOWSKI1, ADRIAN MAŁCZUK2, ANDRZEJ STASIAK3, MACIEJ PAWLAK4 Abstract The paper presents the results of the conducted tests of torsional stiffness of the VOSCO S106 passenger car, as well as the validation process of these tests by means of numerical analyses using the FEM finite element method. The most important element of the vehicle structure is the part of the spatial frame or the safety cage. Engine, brake system, fuel system and steering system, suspension as well as body and parts, their mounting nodes, hinges, locks, etc. are attached to the frame. The frame must therefore have adequate strength to protect the driver in the event of a tipover or impact. The frame is usually made of steel pipes with the prescribed dimensions and strength according to regulations. The torsional stiffness of the vehicle chassis has a significant influence on its driveability and therefore is an important parameter to measure. In this article, the torsional stiffness of the vehicle frame is calculated experimentally, which was then verified by finite element analysis (FEM) using the Altair HyperWorks program. Keywords: vehicle torsional stiffness; FEM; FEA; validation; passive safety of the vehicle 1. Introduction To check the torsional stiffness of the frame experimentally, a special support structure has been made, and fastening brackets have been made to reduce displacement and ro- tation from all axes and directions [41]. A load was also applied and the deflection was measured using a dial indicator. -

Razvoj Automobilske Industrije U Istočnoj Europi

Razvoj automobilske industrije u Istočnoj Europi Fuštin, Ivan Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, Faculty of Science / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:217:444560 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: Repository of Faculty of Science - University of Zagreb Sveučilište u Zagrebu Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Geografski odsjek Ivan Fuštin Razvoj automobilske industrije u Istočnoj Europi Prvostupnički rad Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Zoran Stiperski Ocjena: _______________________ Potpis: _______________________ Zagreb, 2020. godina. TEMELJNA DOKUMENTACIJSKA KARTICA Sveučilište u Zagrebu Prvostupnički rad Prirodoslovno-matematički fakultet Geografski odsjek Razvoj automobilske industrije u Istočnoj Europi Ivan Fuštin Izvadak: U ovom radu cilj je analizirati razvoj i propast automobilske industrije te njezinu revitalizaciju. Utvrditi uzroke propasti automobilskih kompanija u promatranom prostoru te navesti faktore relokacije iste. Također, usporediti čimbenike jače zastupljenosti automobilske industrije u državama u promatranom prostoru. 22 stranica, 1 grafičkih priloga, 1 tablica, 3 bibliografskih referenci; izvornik na hrvatskom jeziku Ključne riječi: automobilska industrija, socijalizam, propast, revitalizacija Voditelj: prof. dr. sc. Zoran Stiperski Tema prihvaćena: 13. 2. 2020. Datum obrane: -

Rdsg 2016-Sk<0142>

ROCZNIKI DZIEJÓW SPOŁECZNYCH I GOSPODARCZYCH Tom LXXVI – 2016 HUBERT WILK Instytut Historii PAN PRÓBA MODERNIZACJI POLSKIEGO PRZEMYSŁU MASZYNOWEGO W DRUGIEJ POŁOWIE LAT 60. PRZYPADEK FIATA 125P Tempo postępu technicznego narzuca nam życie, narzuca nam sytuacja, świat, w któ- rym żyjemy. Władysław Gomułka1 Zarys treści: Tekst dotyczy podjętej w latach 60. XX w. próby zmodernizowa- nia polskiego przemysłu maszynowego. Działania decydentów zostały przed- stawione na przykładzie negocjacji i podpisania kontraktu licencyjnego na produkcję w FSO nowego samochodu fi ata 125p. Zawarcie umowy z włoskim Fiatem i rozpoczęcie wytwarzania średniolitrażowej osobówki miało mieć pozy- tywny wpływ na strukturę eksportu przemysłu maszynowego. The content outline: The paper focuses on the attempts of modernising the Polish machine industry in the 1960s. The undertakings of the decision- -makers are illustrated through the case of negotiating and signing license contract for the production of new motor vehicle, Fiat 125p, by the FSO. The cooperation with the Italian automobile company Fiat and the production of a car with mid-sized engine was meant to positively infl uence the structure of the export sector of the machine industry. Słowa kluczowe: PRL, przemysł motoryzacyjny, samochody, motoryzacja, duży fi at, lata 60. XX w. Keywords: Polish People’s Republic, automotive industry, cars, motorization, Fiat 125p, the 1960s 1 Przemówienie końcowe Władysława Gomułki podczas X Plenum Komitetu Cen- tralnego PZPR w dniu 18 kwietnia 1962 r., w: X Plenum Komitetu Centralnego Polskiej Zjednoczonej Partii Robotniczej w dniach 16–18 IV 1962 r., Warszawa 1962, s. 547. http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/RDSG.2016.14 412 Hubert Wilk Po październikowym przełomie społeczeństwo Polski coraz odważ- niej zaczynało domagać się dostępu do samochodów. -

Summary of Background and Experience Bogdan

SUMMARY OF BACKGROUND AND EXPERIENCE BOGDAN THADDEUS FIJALKOWSKI Full Professor of Cracow University of Technology in Krakow and State Higher Vocational School in Nowy Sacz, Poland Academic Training Master of Science Electrics, Szczecin University of Technology (Politechnika Szczecinska), at present West-Pomeranian University of Technol- ogy (Zachodnio-Pomorski Uniwersytet Technologiczny), Szczecin, Poland, 1959 Doctor of Philosophy Electronics, Mining and Metallurgical Academy (Akademia Gorniczo-Hutnicza), Cracow, Poland, 1965 Doctor of Science Dynamics, Poznan University of Technology (Politechnika Poznanska), Poznan, Poland, 1988 Titular Professor Engineering Sciences, Cracow University of Technology (Politechnika Krakowska), Cracow, Poland, 1997 Full Professor Engineering Sciences, Cracow University of Technology (Politechnika Krakowska), Cracow, Poland, 2000 Professional Experience 1958-61 Teaching Assistant, Chair of Theoretical Electrotechnics, Szczecin University of Technology (Politechnika Szczecinska), Szczecin, Poland 1961-65 Teaching Senior Assistant, Chair of Mining Electrotechnics, Mining and Metallurgical Academy (Akademia Gorniczo-Hutnicza), Cracow, Poland 1965-68 Assistant Professor, Chair of Mining Electrotechnics, Mining and Metallurgi- cal Academy (Akademia Gorniczo-Hutnicza), Cracow, Poland 1968-69 Consultants for Automation and Mechanisation Works of the Non-ferrous Metal Industry - "ZAM", Kety, Poland 1968-72 Assistant Professor and Chairman, Mining Automation and Cybernetics Laboratory, Mining Electrotechnics Institution, -

Innovation in the European Value Chain: the Case of the Romanian Automotive Industry***

CES Working Papers – Volume VII, Issue 1 INNOVATION IN THE EUROPEAN VALUE CHAIN: THE CASE OF THE ROMANIAN AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY*** Alina Petronela NEGREA* Valentin COJANU** Abstract: Entrepreneurs’ and regional stakeholder’s capacity to turn knowledge, skills and competencies into sustainable competitive advantage is crucial to a region' economic performance. The article attempts to reveal their synergy by gathering evidence in the particular context of the Romanian automotive industry. Based on primary data collected through structured interviews and experiential visits, the research is organized around three investigative themes: (1) entrepreneurs’ approach to and perception on innovation, (2) factors affecting innovation, and (3) networking and knowledge diffusion in the regional productive environment. The findings emphasize the convergent opinion of the regional stakeholders on the vital role innovation plays at the current stage of the industry and the key role entrepreneurs have in stimulating innovation in the regional context. A series of three factors underlay the innovative performance at regional and industry level, namely the presence of an innovation friendly business environment, entrepreneurs’ personality, as well as the external competitive environment. Keywords: automotive, entrepreneurship, technology, innovation, Romania JEL Classification: L62, O03 Introduction Entrepreneurship and innovation are staples of any business schools’ curricula. The pair concept has been studied for sufficiently long time to suggest that policy makers are left with the only option of considering their circular causation on their economic agenda. However, the researchers have yet to investigate the conditions under which the reciprocal influence is most likely to eventuate in a virtuous circle, or, alternatively, to escape a vicious one. Attempts to place the two concepts in a territorial context – for example, at which level, national or regional, is it more appropriate to spur innovation and encourage entrepreneurship? – add more issues to the debate. -

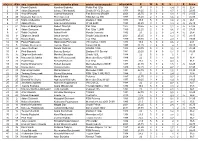

Miejsce Ekipa Imię I Nazwisko Kierowcy Imię I Nazwisko Pilota Marka I Model Pojazdu Rok Pojazdu R W a Q S I P Suma 1 13 Paweł

miejsce ekipa imię i nazwisko kierowcy imię i nazwisko pilota marka i model pojazdu rok pojazdu R W A Q S I P Suma 1 13 Paweł Głębicki Karolina Głębicka Polski Fiat 125p 1968 17 3 3 0 1,4 3 -5 22,4 2 34 Adam Bojanowski Łukasz Chlorkowski Skoda S110L De Luxe 1973 18,25 5 2 0 1,7 1 -5 22,95 3 56 Artur Wołowski Joanna Wołowska Fiat Seicento BRUSH 2003 25,75 0 1 0 1,8 1 -5 24,55 4 45 Krzysztof Kwiecień Piotr Kwiecień FSO Syrena 105 1973 18,25 2 1 0 1,6 2 24,85 5 23 Marta Godlewska Jolanta Wróbel Zastava 1100p 1978 19,5 5 3 0 1,6 2 -5 26,1 6 31 Adam Wierny Agnieszka Mocarska W124 E280 1993 23,25 3 1 0 1,9 2 -5 26,15 7 21 Mateusz Budzyński Robert Tkaczyk Fiat 126p 1977 19,25 5 2 0 1,1 5 -5 27,35 8 4 Adam Gorczyca Basia Kryczałło Fiat 126p 1.2MPI 1989 22,25 2 1 0 0,6 7 -5 27,85 9 51 Rafał Chyliński Adrian Kreft Honda Concerto 1992 23 2 2 0 2,4 4 -5 28,4 10 9 Zbigniew Jarosik Jakub Jarosik Skoda Czołg Octavia 2001 25,25 3 1 0 1,2 3 -5 28,45 11 14 Maciej Kopiś Mateusz Kopiś Fiat 126p 1979 19,75 2 3 1 2,3 1 29,05 12 48 Paweł Pająkowski Małgorzata Pozorska VW Garbus 1303S 1974 18,5 5 3 0 0,6 2 29,1 13 5 Bartosz Mielczarek Tomasz Myszk Ikarus 260.04 1985 21,25 2 4 0 2 1 30,25 14 20 Jacek Woźniak Dorota Woźniak SKODA 105S 1983 20,75 5 0 0 3,2 2 30,95 15 8 Piotr Bartnicki Bartosz Burdzel Zastava 101 Special 1981 20,25 5 4 0 1,7 5 -5 30,95 16 36 Zbigniew Borkowski Monika Skoczylas Skoda 120L 1988 22 5 3 0 0 1 31 17 18 Marzena Stefańska Marek Pietruszewski Mercedes-Benz 420SEC 1988 22 5 3 1 0,4 0 31,4 18 33 Paweł Kępa Krzysztof Banach Fiat 125p 1982 20,5 -

BOPI Nr. 2/2003

!"#$#%&'()'*+,+'-).+/%'#.0).1##'2#'34/$# 5%$%/)2+#'6'/!37.#, 5%&)+#.'!"#$#,& ()' -/!-/#)+,+)'#.(%*+/#,&4 *)$1#%.),'34/$# 8888888888 9 9::; -<=>?@AB'>A'CABA'CDE 28 februarie'9::; BULETIN OFICIAL DE PROPRIETATE INDUSTRIALĂ PUBLICAŢIE OFICIALĂ EDITATĂ DE OFICIUL DE STAT PENTRU INVENŢII ŞI MĂRCI, ÎN 12 VOLUME ANUAL, ÎN FUNCŢIE DE NUMĂRUL CERERILOR DE ÎNREGISTRARE A MĂRCILOR, A CERTIFICATELOR DE ÎNREGISTRARE ŞI DE REÎNNOIRE A MĂRCILOR ACORDATE. Costul estimativ al abonamentului anual este de 5.800. 000 lei, exclusiv cheltuielile de difuzare. Exemplarele individuale au preţul de 550.000 lei/ număr, estimativ în limita stocurilor disponibile, exclusiv cheltuielile de difuzare. Plata se face anticipat în contul Oficiului de Stat pentru Invenţii şi Mărci nr.50.03.4266081 TREZORERIA MUNICIPIULUI BUCUREŞTI ______________________________________________ Colegiu de redacţie: Ştefan Cocoş Mimi Bularda Coperta: Cristina-Maria Bararu Tipărit la: Tipografia O.S.I.M. sub comanda nr. 84/24.02.2003 BULETIN OFICIAL DE PROPRIETATE INDUSTRIALA Nr.2 2003 CUPRINS GENERAL Directia-Redactia-Administratia l. CAPITOL MĂRCI: OFICIUL DE STAT PENTRU 1. Tabel cu mărcile înregistrate: -în ordinea nr. de depozit..........................................11 INVENTII SI MARCI -în ordinea nr.de marcă.............................................37 Str. Ion Ghica nr.5, sect.3 -în ordinea alfabetică numai pentru mărcile verbale şi telefon:3151965; 3151964; combinate...................................................................41 3145964; 3145965; 3145966; -in ordinea alfabetica -

Raportul Administratorilor 2020

ACTIVE CONEXE S.A. RAPORTUL ADMINISTRATORILOR - conform situatiilor financiare aferente anului 2020- 1 CUPRINS: I. BAZA RAPORTULUI .................................................................................................................3 II. DATE DE IDENTIFICARE ............................................................................................................3 III. ANALIZA ACTIVITATII ..............................................................................................................3 3.1. Date de infiintare .................................................................................................................... 3 3.2. Participari la capitalul social al altor societati: ....................................................................... 4 3.3. Conducerea societatii ............................................................................................................. 4 3.4. Activitatea de baza ................................................................................................................. 7 3.5. Activitatea de achizitii .......................................................................................................... 11 3.6. Activitatea juridica – litigii .................................................................................................... 13 IV. ACTIVITATEA ECONOMICO – FINANCIARA LA DATA DE 31.12.2020 ......................................... 13 4.1 Informatii generale .............................................................................................................. -

Studiul Spos4

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Țurlea, Geomina; Cojanu, Valentin; Alexoaei, Alina; Neculau, Georgiana; Petrariu, Ioan-Radu Research Report Avantajele competitive ale României pe piaţa internă a UE Strategy and Policy Studies (SPOS), No. 2013,4 Provided in Cooperation with: European Institute of Romania, Bucharest Suggested Citation: Țurlea, Geomina; Cojanu, Valentin; Alexoaei, Alina; Neculau, Georgiana; Petrariu, Ioan-Radu (2014) : Avantajele competitive ale României pe piaţa internă a UE, Strategy and Policy Studies (SPOS), No. 2013,4, ISBN 978-606-8202-41-9, European Institute of Romania, Bucharest This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/141818 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Avantajele competitive ale României pe piaţa internă a UE STUDII DE STRATEGIE ŞI POLITICI 2013 - nr. -

Samochody Z Żerania 1951-1977 / Marek Kuc. – Warszawa, 2017 Spis

Samochody z Żerania 1951-1977 / Marek Kuc. – Warszawa, 2017 Spis treści Od autora 7 Podziękowania 9 Powstanie i rozwój Fabryki Samochodów Osobowych 11 FSO Warszawa (1951-1973) 18 Warszawa M20 (1951) 18 Warszawa Pickup (prototyp 1955) 20 Warszawa M20 U (prototyp 1956) 21 Warszawa M20 model 1957 (później Warszawa 200) 21 Warszawa M20 Sanitarka (od 1957) 23 Warszawa M20 (pakiet modernizacji 1958 i 1959) 23 Warszawa 200P Pickup (od 1958) 24 Warszawa Ghia (prototypy 1959) 25 Warszawa 201 (od 1960) 26 Warszawa sedan (przedprototypy 1961) 27 Warszawa 202 (od 1962) 29 Warszawa 201P/202P Pickup, 201F/202F Furgon i Furgon przeszklony oraz 202A sanitarka (od 1963) 29 Warszawa 203/204, 223/224 w różnych wersjach (1964) 30 Warszawa 210 (prototyp 1964) 32 Warszawa 203 Taxi/204 Taxi (od 1965) 34 Warszawa ze zmodernizowanym układem napędowym (prototypy 1965-1969) 34 Warszawa ze zmodernizowanym przodem (prototypy 1967) 35 Warszawa - zmiana oznaczenia modelu i zakończenie produkcji (1968-1973) 37 FSO Syrena (1957-1972) 40 Syrena (prototypy 1954-1957) 40 Syrena 100 (od 1957) 42 Syrena z płytą podłogową zamiast ramy i silnikiem S-16 (prototyp 1958) 43 Syrena 101 (1960-1962) 43 Syrena Mikrobus (prototyp 1960) 44 Syrena Sport (prototyp 1960) 45 Syrena Kombi (prototyp 1961) 46 Syrena 104 (prototyp 1961) 47 Syrena 102 (1962-1963) 48 Syrena 102 S (1963) 49 Syrena 103/103 S (1963-1966) 49 Syrena 110 (prototypy 1964-1966) 50 Syrena 104 (1966-1972) 53 Syrena 104 Pickup/104 Furgon (prototypy 1968) 54 Syrena „laminat" (prototyp 1968) 54 Syrena 607 (prototyp 1970/1971) -

Central Europe Automotive Report

AUSTRIA BULGARIA CZECH REPUBLIC HUNGARY CENTRAL POLAND ROMANIA SLOVAK REPUBLIC SLOVENIA EUROPE COVERING THE AUTOMOTIVE CENTRAL EUROPEAN AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY REPORT February 1997 Volume II, Issue 2 ISSN 1088-1123 ™ ture (1995-1997) amounts Romania to USD 500,000,000. As of November 1996, the com- PROFILE pany had 4,800 employees. ROMANIA Commercial Auto Leasing Daewoo & Dacia Battle for Market Daewoo plans to invest Hits Romania an additional USD 550 mil- Share; Suppliers Modernizing lion (USD 77 million in cash and USD 473 million AutoLease is Romania’s first dedicated auto in equipment) in its leasing company. The company will provide Market Highlights Romanian factory. Daewoo hopes to pro- 2-year cross-border finance leases to interna- duce 300,000 cars annually by the year 2000. tional and Romanian companies doing business In early 1997, Romanian truck manufactur- “We are not going to make any compromise in Romania. er Roman S.A. will put into service a new on the quality of the cars produced in flexible crankshaft manufacturing line. The Craiova,” stresses Mr. Dong-Kyu Park, the Mike Morris, line will use machines imported from the company’s Chairman. (See CEAR Vol. 1, Founder and companies Boeringer, Hegenscheidt, Naxos- Issue 3 for a Profile interview of Mr. Park). CEO of Union, and Adcole. Roman also plans to Daewoo also intends to start assembly (SKD) AutoLease, is a begin production of 110-115 hp truck engines of 1-ton light trucks at ARO’s facilities in Harvard MBA that meet Euro-2 standards. The engines are Campulung Muscel. and financier currently being tested at the A.V.L. -

Dolj County Dolj Originally Meant

Dolj County Dolj originally meant "lower Jiu", as opposed to Gorj (upper Jiu) is a county of Romania on the border with Bulgaria, in Oltenia, with the capital city at Craiova. In 2011, it had a population of 660,544 and a population density of 89/km2 (230/sq mi). • Romanians – over 96% • Romani – 3% • Others almost 1%. Geography This county has a total area of 7,414 km2 (2,863 sq mi). The entire area is a plain with the Danube on the south forming a wide valley crossed by the Jiu River in the middle. Other small rivers flow through the county, each one forming a small valley. There are some lakes across the county and many ponds and channels in the Danube valley. 6% of the county's area is a desert. Neighbours • Olt County to the east. • Mehedinți County to the west. • Gorj County and Vâlcea County to the north. • Bulgaria – Vidin Province to the southwest, Montana and Vratsa provinces to the south. Economy Agriculture is the county's main industry. The county has a land that is ideal for growing cereals, vegetables and wines. Other industries are mainly located in the city of Craiova, the largest city in southwestern Romania. The county's main industries: • Automotive industry – Ford has a factory. • Heavy electrical and transport equipment – Electroputere Craiova is the largest factory plant in Romania. • Aeronautics ; ITC • Chemicals processing ; Foods and beverages • Textiles ; Mechanical parts and components There are two small ports on the shore of the Danube river – Bechet and Calafat. Tourism Major tourist attractions: The city of Craiova; The city of Calafat; Fishing on the Danube; The city of Băilești.