Economic Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

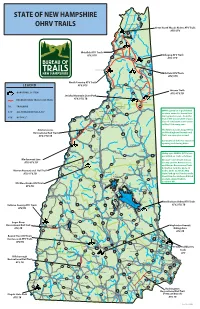

State of New Hampshire Ohrv Trails

STATE OF NEW HAMPSHIRE Third Connecticut Lake 3 OHRV TRAILS Second Connecticut Lake First Connecticut Lake Great North Woods Riders ATV Trails ATV, UTV 3 Pittsburg Lake Francis 145 Metallak ATV Trails Colebrook ATV, UTV Dixville Notch Umbagog ATV Trails 3 ATV, UTV 26 16 ErrolLake Umbagog N. Stratford 26 Millsfield ATV Trails 16 ATV, UTV North Country ATV Trails LEGEND ATV, UTV Stark 110 Groveton Milan Success Trails OHRV TRAIL SYSTEM 110 ATV, UTV, TB Jericho Mountain State Park ATV, UTV, TB RECREATIONAL TRAIL / LINK TRAIL Lancaster Berlin TB: TRAILBIKE 3 Jefferson 16 302 Gorham 116 OHRV operation is prohibited ATV: ALL TERRAIN VEHICLE, 50” 135 Whitefield on state-owned or leased land 2 115 during mud season - from the UTV: UP TO 62” Littleton end of the snowmobile season 135 Carroll Bethleham (loss of consistent snow cover) Mt. Washington Bretton Woods to May 23rd every year. 93 Twin Mountain Franconia 3 Ammonoosuc The Ammonoosuc, Sugar River, Recreational Rail Trail 302 16 and Rockingham Recreational 10 302 116 Jackson Trails are open year-round. ATV, UTV, TB Woodsville Franconia Crawford Notch Notch Contact local clubs for seasonal opening and closing dates. Bartlett 112 North Haverhill Lincoln North Woodstock Conway Utility style OHRV’s (UTV’s) are 10 112 302 permitted on trails as follows: 118 Conway Waterville Valley Blackmount Line On state-owned trails in Coos 16 ATV, UTV, TB Warren County and the Ammonoosuc 49 Eaton Orford Madison and Warren Recreational Trails in Grafton Counties up to 62 Wentworth Tamworth Warren Recreational Rail Trail 153 inches wide. In Jericho Mtn Campton ATV, UTV, TB State Park up to 65 inches wide. -

North Maine Woods2013 $3

experience the tradition North Maine Woods2013 $3 On behalf welcomeof the many families, private corporations, conservation organizations and managers of state owned land, we welcome you to this special region of Maine. We’re proud of the history of this remote region and our ability to keep this area open for public enjoyment. In addition to providing remote recreational opportunities, this region is also the “wood basket” that supports our natural resource based economy of Maine. This booklet is designed to help you have a safe and enjoyable trip to the area, plus provide you with important information about forest resource management and recreational use. P10 Katahdin Ironworks Jo-Mary Forest Information P14 New plan for the Allagash Wilderness Waterway P18 Moose: Icon of P35 Northern Region P39 Sharing the roads the North Woods Fisheries Update with logging trucks 2013 Visitor Fees NMW staff by photo RESIDENT NON-RESIDENT Under 15 .............................................................. Free Day Use & Camping Age 70 and Over ............................................... Free Day Use Per Person Per Day ...................................................$7 ................ $12 Camping Per Night ....................................................$10 ............. $12 Annual Day Use Registration ...............................$75 ............. N/A Annual Unlimited Camping ..................................$175 .......... N/A Checkpoint Hours of Operation Camping Only Annual Pass ...................................$100 .......... $100 Visitors traveling by vehicle will pass through one of the fol- lowing checkpoints. Please refer to the map in the center of Special Reduced Seasonal Rates this publication for locations. Summer season is from May 1 to September 30. Fall season is from August 20 to November 30. Either summer or fall passes NMW Checkpoints are valid between August 20 and September 30. Allagash 5am-9pm daily Caribou 6am-9pm daily Seasonal Day Use Pass ............................................$50 ............ -

Provide More Recreation Page: 1

Provide More Recreation Page: 1 INTRODUCTION This project documents both the existing value and potential of New England’s working forest lands: Value – not only in terms of business opportunities, jobs and income – but also nonfinancial values, such as enhanced wildlife populations, recreation opportunities and a healthful environment. This project of the New England Forestry Foundation (NEFF) is aimed at enhancing the contribution the region’s forests can make to sustainability, and is intended to complement other efforts aimed at not only conserving New England’s forests, but also enhancing New England’s agriculture and fisheries. New England’s forests have sustained the six-state region since colonial settlement. They have provided the wood for buildings, fuel to heat them, the fiber for papermaking, the lumber for ships, furniture, boxes and barrels and so much more. As Arizona is defined by its desert landscapes and Iowa by its farms, New England is defined by its forests. These forests provide a wide range of products beyond timber, including maple syrup; balsam fir tips for holiday decorations; paper birch bark for crafts; edibles such as berries, mushrooms and fiddleheads; and curatives made from medicinal plants. They are the home to diverse and abundant wildlife. They are the backdrop for hunting, fishing, hiking, skiing and camping. They also provide other important benefits that we take for granted, including clean air, potable water and carbon storage. In addition to tangible benefits that can be measured in board feet or cords, or miles of hiking trails, forests have been shown to be important to both physical and mental health. -

Seboomook Unit Management Plan

Seboomook Unit Management Plan Maine Department of Conservation Bureau of Parks and Lands March 2007 Table of Contents Acknowledgements I. Introduction 1 About This Document 1 What is the Seboomook Unit? 2 II. The Planning Process 4 Statutory and Policy Guidance 4 Public Participation 4 III. The Planning Context 6 Acquisition History 6 Relation to North Maine Woods 6 Parks and Lands Overlap 8 Public-Private Partnerships 8 New Water-Based Recreation Opportunities 9 Remote Location 10 Public Recreation Resources in the Broader Region 10 New Regional Recreation Opportunities - Public/Private Initiatives 16 Trends in Recreation Use 18 Summary of Planning Implications 19 IV. The Character and Resources of the Unit 20 Overview 20 Seboomook and Canada Falls Parcels 24 St. John Ponds Parcel 46 Baker Lake Parcel 52 Big Spencer Mountain Parcel 60 V. A Vision for the Unit 66 VI. Resource Allocations 69 Overview Summary 69 Seboomook Lake Parcel 82 Canada Falls Parcel 85 Baker Lake Parcel 86 St. John Ponds Parcel 88 Big Spencer Mountain Parcel 89 VII. Management Recommendations 90 Seboomook and Canada Falls Parcels 90 St. John Ponds Parcel 95 Baker Lake Parcel 95 Big Spencer Mountain Parcel 97 VIII. Monitoring and Evaluation 98 IX. Appendices A. Advisory Committee Members B. Summary of Management Issues C. Bureau Response to Written Public Comments D. Deed Restrictions and Agreements E. Guiding Statutes F. Glossary i G. References H. Natural Resource Inventory of the Bureau of Parks and Lands Seboomook Unit (under separate cover) I. Timber Harvest -

Explore New England Has Just Released Its First Feature, Four

Explore New England has just released its first feature, four season, film on NESN called Seeking The Source [ click here to see press release ] Please CLICK HERE or see below to watch the film in its entirety, or save the link to watch over the holidays. Film is currently airing on NESN to 5+M Homes across the Northeast and ratings data and feedback is wildly exceeding all our expectations. Television & Film Series will debut Season #1 Spring 2020 Feature Film: Seeking the Source Picture a land of rolling hills, crystalline lakes, secluded ponds, verdant forest, and a mighty river that flows through its heart. Add some fascinating history and equally fascinating people and you have “Seeking the Source,” the first hour-long film from Explore New England. Join host and outdoor writer Tom Richardson as he explores New Hampshire’s Great North Woods through a variety of outdoor activities, including camping, hiking, fishing, paddling, ATV riding, snowmobiling, boating, hunting and more. Along the way, you’ll learn about the region through the eyes of local residents who call this place home—and are willing to share some of their secrets. Stunning cinematography by acclaimed filmmaker AJ Derosa captures the changing scenery and local wildlife as the film moves through the seasons, yet always returns to the great river that has shaped so much of the region’s unique history and culture. Explore New England's Season #1 Episodic / Show Schedule 1 Winnipesaukee Awakening (Lake Winnipesaukee, NH) ENE travels to New Hampshire’s Lake Winnipesaukee shortly after ice-out to sample spring fishing for landlocked salmon and a kayak trip to Stonedam Island, where the public is welcome to hike and experience the wild side of Lake Winnie. -

Economic Impacts of the 13 Mile Woods Community Forest in Errol, New Hampshire

Economic Impacts of the 13 Mile Woods Community Forest in Errol, New Hampshire Prepared for the Community Forest Collaborative By Elizabeth Reaves and Marta Ceroni Donella Meadows Institute (for Green Compass LLC), 2 Beaver Meadows Road, Norwich, VT 05055 [email protected], 802-432-8930 1 Acknowledgements This work is a reflection of the generosity of many people who gave their time, shared their knowledge, and continue to work hard to support the Town of Errol, the 13 Mile Woods Community Forest, and the Community Forest Ownership Model. In particular, the authors would like to acknowledge 13 Mile Woods Association members Bill Freedman, Charlie Kurtz, and Pierre Rousseau as well as New Hampshire Fish and Game Region 1, Wildlife Biologist, Will Staats, Fisheries Biologist, Diane Timmins, and Wildlife Programs Supervisor, Kent Gustafson. Phoebe Backler provided great insight into the economic benefits of paddlers along the Northern Forest Canoe Trail. Greg Ainsworth, Consulting Forester for the 13 Mile Woods provided timber harvest data and knowledge about the past, present, and future of the forest industry in New Hampshire. Special thanks to Julie Renaud Evans, Director of Forestry for The Northern Forest Center. Julie provided invaluable knowledge, time, and resources about the benefits of community ownership of forestland and insight into the unique and special ecological, recreation, and timber stocking attributes of the 13 Mile Woods Community Forest. J.T. Horn, Project Manager for The Trust for Public Land, provided great insight into the unique qualities of the Great North Woods, perspective on the history of forest ownership and management in New England and the balance between conservation and working land, the process involved in the purchase of the 13 Mile Woods parcels, and the role The Trust for Public Land played in the process. -

Making Sense of Scientific Names

SUMMER ’12 A NEW WAY OF LOOKING AT THE FOREST Making Sense of Scientific Names The Remarkable Lives of Woodland Ants A Paper Mill Remembered No Dry Matter: The Wood – Moisture Relationship Bioluminescent Fungi, Balsam Fir Pillows, White-nose Update, and much more $5.95 WOOD_SUM12_COVERS.indd 3 5/16/12 12:45:35 PM A Consulting Forester can help you Markus Bradley, Ben Machin, Mike Scott Paul Harwood, Leonard Miraldi Make decisions about Redstart Forestry Harwood Forestry Services, Inc. managing your forestland Juniper Chase, Corinth, VT 05039 P.O. Box 26, Tunbridge, VT 05077 (802) 439-5252 (802) 356-3079 Design a network of trails www.redstartconsulting.com [email protected] Anita Nikles Blakeman Ben Hudson Woodland Care Forest Management Hudson Forestry Improve the wildlife P.O. Box 4, N. Sutton, NH 03260 P.O. Box 83, Lyme, NH 03768 habitat on your property (603) 927-4163 (603) 795-4535 [email protected] [email protected] Negotiate a contract Herbert Boyce, ACF, CF M.D. Forestland Consulting, LLC Deborah Boyce, CF (802) 472-6060 with a logger and Northwoods Forest Consultants, LLC David McMath supervise the job 13080 NYS Route 9N, Jay, NY 12941 Cell: (802) 793-1602 (518) 946-7040 [email protected] [email protected] Beth Daut, NH #388 Improve the quality of Cell: (802) 272-5547 Gary Burch [email protected] your timber Burch Hill Forestry 1678 Burch Road, Granville, NY 12832 Scott Moreau (518) 632-5436 Greenleaf Forestry [email protected] P.O. Box 39, Westford, VT 05494 (802) 343-1566 cell Alan Calfee, Michael White (802) 849-6629 Calfee Woodland Management, LLC [email protected] P.O. -

Take Me Fishing!™

WHY FISH NH? New Hampshire Fish and Game Department Just step outside to find scenic fishing here in wild Take Me New Hampshire – we’ve got great fishing around every corner: ™ u Fishing! 12,000 miles of river and streams. u 975 lakes and ponds. u Fishing for bass, trout, salmon, pike, walleye, pickerel, Great North Woods perch and more… u Record big fish – and some wily wild fish too! u Scenic vistas and wildlife abound. u Nearly a million trout stocked each year – just for you! Learn more about fishing in New Hampshire at fishnh.com © SCULPIES / DREAMSTIME.COM Shoreline Fishing Guide COMPOSITE IMAGE / DREAMSTIME.COM COMPOSITE IMAGE New Hampshire Fish and Game Connecting you to life outdoors™ NEW HAMPSHIRE FISH AND GAME DEPARTMENT 11 Hazen Drive l Concord, NH 03301 l (603) 271-2501 Your purchase of fishing tackle and motorboat fuels, along with license sales, helps fund sport fish restoration and management in New Hampshire fishnh.com North Country Fishing – The Great Escape! PITTSBURG CLARKSVILLE Whether you’re fly-fishing for big rainbows or casting a line while enjoying a riverside picnic, fishing New Hampshire’s Great North Woods will be an experience to remember. Relax COLEBROOK in scenic natural surroundings. Catch a glimpse of moose, osprey or loons. Pull in a fighting brookie. There’s no better DIXVILLE COLUMBIA place than New Hampshire’s North Country to get away from it ERROL all and go fishing. Lake From world-class fly-fishing waters to serene lakes and Umbagog welcoming riverbank waysides, use this handy guide to find NORTH STRATFORD your own North Country fishing hole. -

The Northern Forest Canoe Trail Membership & Order Form

The Northern Forest Canoe Trail Membership & Order Form www.NorthernForestCanoeTrail.org Join the Northern Forest Canoe Trail today! NFCT is a member-supported non-profit organization. Membership dues enable NFCT to carry out its goal of renewing the bonds between communities and their waterways in the Northern Forest. Spanning 740 miles, four states, a Canadian province, and numerous watersheds, this long-distance paddle trail is an exceptional recreational asset. Threading through more than 40 communities, it is also an intriguing cultural journey. Membership Benefits: • Become part of a national model for community-based water trail design and management. • Join a grassroots effort to preserve and celebrate the human heritage and natural beauty of the Northern Forest. • Gain access to a members-only section of our website with continually updated route and travel information, stories from the Trail, local highlights and more. Members will receive: ✔ NFCT decal ✔ Overview maps of the Trail ✔ Section descriptions of the NFCT ✔ Road route description of the NFCT ✔ A list of recommended books, maps and guides ✔ Bi-annual newsletter, Currents and Communities Become an NFCT member today! A Mission of People and Place The mission of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail is to celebrate the rich human heritage and diverse natural environment of the Northern Forest by establishing and stewarding a water trail tracing historic Native American travel routes across New York, Vermont, Québec, New Hampshire, and Maine. ✔ Yes, I would like to support the Northern Forest Canoe Trail today! ❑ $500 ~ Champion ❑ Check enclosed ❑ $250 ~ Sponsor Please charge my ❑ Visa ❑ MC ❑ AmEx ❑ Discover ❑ $100 ~ Benefactor Card # _________________________________ Exp. -

Maine Woods : Vol. 35, No. 6 September 05,1912 (Outing Edition)

VOL. XXXV. NO. 6 PHILLIPS, MAINE, THURSDAY, SEPT. 5, 1912 PRICE 4 CEN T MINK MAKE HOME S T E V E N S * AT MINGO SPRINGS Favorite Rifle No. 17 “ Bull's Eye Kind. Swim About Near the Wharf and _ CLUB ASS. YOUR DEALER Attract Much Attention Repeating Shotguns SHOT SHELLS ‘‘The most popular ^ small bore rifle made. <► from Guests. and # The old original black Factory Loaded Shot Shells powder shells. A beautiful example of careful, accurate (Special to Maine Woods). These two make as satisfactory a combination for Introduced more than fifty workmanship. - Mingo Springs, Sept. 2.—The sum bird or small animal shooting as you could get. All year* ago. More popular mer has ended and nearly 30 guests Winchesters are hard, close shooters, giving fine today than ever. ' Favorite barrels remain to enjoy autumn days. “ There penetration and an even spread of shot. In balance, ease of action and quickness of handling they are The perfect ignition of the are rifled more ac is. only one thing we would change all you could desire.*.Winchester loaded shells— No. 2 primer insures a quick, and that is the weather’’ said a curate than many The Red Brand—“ Leader” and “ Repeater” snappy load seldom found in New Yorker this morning. black powder shells. rifle3 selling as high smokeless, and “ Nublack” and “ New Rival” black, If there ever was a summer with For all shotguns. as $50.00. are well made and loaded in a uniform manner with as many rainy and cloudy days as all standard brands of powder, shot and wadding. -

By Janis Barth

Mengucci: Lookout BY JANIS BARTH he sky lowered and held only the promise of more snow. A cold sun, pale and milky as birch, T hung low on the horizon. Only a subdued light filtered through the dense crowns of spruce and hemlock-ancient pines, spear-shaped and still. Here, in the soft pine trailings of the forest floor, there are no surveyor's stakes, no carefully tended lot lines. There are, as there have always been, the mountains. Granite-ribbed, the Adirondacks were old when the continent was young. The old logging trail underfoot twists and falls and leads steeply into the past. Time was, the great north woods stretched unbroken, rich in timber. The cross-cut saw of the timberjack broke the winter's silence and the great workhorse rivers, the Raquette and the Grasse, carried highways of logs to the rich markets in Albany and New York City. Along the dark ridges of the high peaks, the wolf, the moose, the cougar, and the lynx lived and died and, as civilization pushed deeper into the vast forests, became a dry footnote in the bureaucratic tally of such things: Extinct to the region. The road is pockmarked and rough and memory lies as thick as dust. In 1885, long before it became fashionable to set aside public parks and preserve the natural landscape for future generations, the State of New York determined that this untamed place should remain forever wild. The creation of the Adirondack Forest Pre serve and, in 1892, the Adirondack Park, guaranteed a natural legacy.