What Can We Learn from Failed International Companies?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Prof. Paul Stephen Dempsey

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2008 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Before Alliances, there was Pan American World Airways . and Trans World Airlines. Before the mega- Alliances, there was interlining, facilitated by IATA Like dogs marking territory, airlines around the world are sniffing each other's tail fins looking for partners." Daniel Riordan “The hardest thing in working on an alliance is to coordinate the activities of people who have different instincts and a different language, and maybe worship slightly different travel gods, to get them to work together in a culture that allows them to respect each other’s habits and convictions, and yet work productively together in an environment in which you can’t specify everything in advance.” Michael E. Levine “Beware a pact with the devil.” Martin Shugrue Airline Motivations For Alliances • the desire to achieve greater economies of scale, scope, and density; • the desire to reduce costs by consolidating redundant operations; • the need to improve revenue by reducing the level of competition wherever possible as markets are liberalized; and • the desire to skirt around the nationality rules which prohibit multinational ownership and cabotage. Intercarrier Agreements · Ticketing-and-Baggage Agreements · Joint-Fare Agreements · Reciprocal Airport Agreements · Blocked Space Relationships · Computer Reservations Systems Joint Ventures · Joint Sales Offices and Telephone Centers · E-Commerce Joint Ventures · Frequent Flyer Program Alliances · Pooling Traffic & Revenue · Code-Sharing Code Sharing The term "code" refers to the identifier used in flight schedule, generally the 2-character IATA carrier designator code and flight number. Thus, XX123, flight 123 operated by the airline XX, might also be sold by airline YY as YY456 and by ZZ as ZZ9876. -

Delta Air Lines Inc /De

DELTA AIR LINES INC /DE/ FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 09/28/98 for the Period Ending 06/30/98 Address HARTSFIELD ATLANTA INTL AIRPORT 1030 DELTA BLVD ATLANTA, GA 30354-1989 Telephone 4047152600 CIK 0000027904 Symbol DAL SIC Code 4512 - Air Transportation, Scheduled Industry Airline Sector Transportation Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2015, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. DELTA AIR LINES INC /DE/ FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 9/28/1998 For Period Ending 6/30/1998 Address HARTSFIELD ATLANTA INTL AIRPORT 1030 DELTA BLVD ATLANTA, Georgia 30354-1989 Telephone 404-715-2600 CIK 0000027904 Industry Airline Sector Transportation Fiscal Year 12/31 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 10 -K [X] ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 1998 OR [ ] TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 1-5424 DELTA AIR LINES, INC. (EXACT NAME OF REGISTRANT AS SPECIFIED IN ITS CHARTER) DELAWARE 58-0218548 (STATE OR OTHER JURISDICTION OF (I.R.S. EMPLOYER INCORPORATION OR ORGANIZATION) IDENTIFICATION NO.) HARTSFIELD ATLANTA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT POST OFFICE BOX 20706 30320 ATLANTA, GEORGIA (ADDRESS OF PRINCIPAL EXECUTIVE OFFICES) (ZIP CODE) REGISTRANT'S TELEPHONE NUMBER, INCLUDING AREA CODE: (404) 715-2600 SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) -

Belgian Aerospace

BELGIAN AEROSPACE Chief editor: Fabienne L’Hoost Authors: Wouter Decoster & Laure Vander Graphic design and layout: Bold&pepper COPYRIGHT © Reproduction of the text is authorised provided the source is acknowledged Date of publication: June 2018 Printed on FSC-labelled paper This publication is also available to be consulted at the website of the Belgian Foreign Trade Agency: www.abh-ace.be BELGIAN AEROSPACE TECHNOLOGIES TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR 4-35 SECTION 1 : BELGIUM AND THE AEROSPACE INDUSTRY 6 SECTION 2 : THE AERONAUTICS INDUSTRY 10 SECTION 3 : THE SPACE INDUSTRY 16 SECTION 4 : BELGIAN COMPANIES AT THE FOREFRONT OF NEW AEROSPACE TRENDS 22 SECTION 5 : STAKEHOLDERS 27 CHAPTER 2 SUCCESS STORIES IN BELGIUM 36-55 ADVANCED MATERIALS & STRUCTURES ASCO INDUSTRIES 38 SABCA 40 SONACA 42 PLATFORMS & EMBEDDED SYSTEMS A.C.B. 44 NUMECA 46 THALES ALENIA SPACE 48 SERVICES & APPLICATIONS EMIXIS 50 SEPTENTRIO 52 SPACEBEL 54 CHAPTER 3 DIRECTORY OF COMPANIES 56-69 3 PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR PRESENTATION OF THE SECTOR SECTION 1 By then, the Belgian government had already decided it would put out to tender 116 F-16 fighter jets for the Belgian army. This deal, still known today as “the contract of the BELGIUM AND THE century” not only brought money and employment to the sector, but more importantly, the latest technology and AEROSPACE INDUSTRY know-how. The number of fighter jets bought by Belgium exceeded that of any other country at that moment, except for the United States. In total, 1,811 fighters were sold in this batch. 1.1 Belgium’s long history in the aeronautics industry This was good news for the Belgian industry, since there was Belgium’s first involvement in the aeronautics sector was an agreement between General Dynamics and the European related to military contracts in the twenties. -

Airline Alliances

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2011 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Open Skies • 1992 - the United States concluded the first second generation “open skies” agreement with the Netherlands. It allowed KLM and any other Dutch carrier to fly to any point in the United States, and allowed U.S. carriers to fly to any point in the Netherlands, a country about the size of West Virginia. The U.S. was ideologically wedded to open markets, so the imbalance in traffic rights was of no concern. Moreover, opening up the Netherlands would allow KLM to drain traffic from surrounding airline networks, which would eventually encourage the surrounding airlines to ask their governments to sign “open skies” bilateral with the United States. • 1993 - the U.S. conferred antitrust immunity on the Wings Alliance between Northwest Airlines and KLM. The encirclement policy began to corrode resistance to liberalization as the sixth freedom traffic drain began to grow; soon Lufthansa, then Air France, were asking their governments to sign liberal bilaterals. • 1996 - Germany fell, followed by the Czech Republic, Italy, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Malta, Poland. • 2001- the United States had concluded bilateral open skies agreements with 52 nations and concluded its first multilateral open skies agreement with Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. • 2002 – France fell. • 2007 - The U.S. and E.U. concluded a multilateral “open skies” traffic agreement that liberalized everything but foreign ownership and cabotage. • 2011 – cumulatively, the U.S. had signed “open skies” bilaterals with more than100 States. Multilateral and Bilateral Air Transport Agreements • Section 5 of the Transit Agreement, and Section 6 of the Transport Agreement, provide: “Each contracting State reserves the right to withhold or revoke a certificate or permit to an air transport enterprise of another State in any case where it is not satisfied that substantial ownership and effective control are vested in nationals of a contracting State . -

Swissair's Collapse

IWIM - Institut für Weltwirtschaft und Internationales Management IWIM - Institute for World Economics and International Management Swissair’s Collapse – An Economic Analysis Andreas Knorr and Andreas Arndt Materialien des Wissenschaftsschwerpunktes „Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft“ Band 28 Hrsg. von Andreas Knorr, Alfons Lemper, Axel Sell, Karl Wohlmuth Universität Bremen Swissair’s Collapse – An Economic Analysis Andreas Knorr and Andreas Arndt Andreas Knorr, Alfons Lemper, Axel Sell, Karl Wohlmuth (Hrsg.): Materialien des Wissenschaftsschwerpunktes „Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft“, Bd. 28, September 2003, ISSN 0948-3837 (ehemals: Materialien des Universitätsschwerpunktes „Internationale Wirtschaftsbeziehungen und Internationales Management“) Bezug: IWIM - Institut für Weltwirtschaft und Internationales Management Universität Bremen Fachbereich Wirtschaftswissenschaft Postfach 33 04 40 D- 28334 Bremen Telefon: 04 21 / 2 18 - 34 29 Telefax: 04 21 / 2 18 - 45 50 E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.iwim.uni-bremen.de Abstract Swissair’s rapid decline from one of the industries’ most renowned carriers into bank- ruptcy was the inevitable consequence of an ill-conceived alliance strategy – which also diluted Swissair’s reputation as a high-quality carrier – and the company’s inability to coordinate effectively its own operations with those of Crossair, its regional subsidiary. However, we hold that while yearlong mismanagement was indeed the driving force behind Swissair’s demise, exogenous factors both helped and compounded -

Before the U.S. Department of Transportation Washington, D.C

BEFORE THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION WASHINGTON, D.C. Application of AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC OPENSKIES SAS IBERIA LÍNEAS AÉREAS DE ESPAÑA, S.A. Docket DOT-OST-2008-0252- FINNAIR OYJ AER LINGUS GROUP DAC under 49 U.S.C. §§ 41308 and 41309 for approval of and antitrust immunity for proposed joint business agreement JOINT MOTION TO AMEND ORDER 2010-7-8 FOR APPROVAL OF AND ANTITRUST IMMUNITY FOR AMENDED JOINT BUSINESS AGREEMENT Communications about this document should be addressed to: For American Airlines: For Aer Lingus, British Airways, and Stephen L. Johnson Iberia: Executive Vice President – Corporate Kenneth P. Quinn Affairs Jennifer E. Trock R. Bruce Wark Graham C. Keithley Vice President and Deputy General BAKER MCKENZIE LLP Counsel 815 Connecticut Ave. NW Robert A. Wirick Washington, DC 20006 Managing Director – Regulatory and [email protected] International Affairs [email protected] James K. Kaleigh [email protected] Senior Antitrust Attorney AMERICAN AIRLINES, INC. Laurence Gourley 4333 Amon Carter Blvd. General Counsel Fort Worth, Texas 76155 AER LINGUS GROUP DESIGNATED [email protected] ACTIVITY COMPANY (DAC) [email protected] Dublin Airport [email protected] P.O. Box 180 Dublin, Ireland Daniel M. Wall Richard Mendles Michael G. Egge General Counsel, Americas Farrell J. Malone James B. Blaney LATHAM & WATKINS LLP Senior Counsel, Americas 555 11th St., NW BRITISH AIRWAYS PLC Washington, D.C. 20004 2 Park Avenue, Suite 1100 [email protected] New York, NY 10016 [email protected] [email protected] Antonio Pimentel Alliances Director For Finnair: IBERIA LÍNEAS AÉREAS DE ESPAÑA, Sami Sareleius S.A. -

Het Turbulente Verhaal Van Een Pionier

SABENA HET TURBULENTE VERHAAL VAN EEN PIONIER CYNRIK DE DECKER HOUTEKIET/FLYING PENCIL Antwerpen / Amsterdam SABENA-press.indd 3 17/09/19 16:22 Inhoud 1 | Brieng ............................................................................................................................................... 7 2 | SNETA start ...................................................................................................................................... 9 3 | Doorstart met Sabena ....................................................................................................... 27 4 | Winst in oorlog ......................................................................................................................... 85 5 | Intercontinentaal, op Amerikaanse leest ........................................................ 101 6 | Sabena tijdens de Koude Oorlog ............................................................................. 133 7 | Feesten in de ies: wentelwieken, Expo en een nieuwe thuis ..... 139 8 | Het straaltijdperk .................................................................................................................. 161 SABENA-press.indd 4 17/09/19 16:22 9 | De gouden Congolese eieren ...................................................................................... 169 10 | Vliegen met een blinde vlek ....................................................................................... 199 11 | In duikvlucht ........................................................................................................................... -

Contractions 7340.2 CHG 3

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION JO 7340.2 CHG 3 SUBJ: CONTRACTIONS 1. PURPOSE. This change transmits revised pages to Order JO 7340.2, Contractions. 2. DISTRIBUTION. This change is distributed to select offices in Washington and regional headquarters, the William J. Hughes Technical Center, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center; to all air traffic field offices and field facilities; to all airway facilities field offices; to all intemational aviation field offices, airport district offices, and flight standards district offices; and to interested aviation public. 3. EFFECTIVE DATE. May 7, 2009. 4. EXPLANATION OF CHANGES. Cancellations, additions, and modifications (CAM) are listed in the CAM section of this change. Changes within sections are indicated by a vertical bar. 5. DISPOSITION OF TRANSMITTAL. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. PAGE CONTROL CHART. See the page control chart attachment. tf ,<*. ^^^Nancy B. Kalinowski Vice President, System Operations Services Air Traffic Organization Date: y-/-<3? Distribution: ZAT-734, ZAT-4S4 Initiated by: AJR-0 Vice President, System Operations Services 5/7/09 JO 7340.2 CHG 3 PAGE CONTROL CHART REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−3 . 1/15/09 CAM−1−1 through CAM−1−3 . 5/7/09 1−1−1 . 6/5/08 1−1−1 . 5/7/09 3−1−15 . 6/5/08 3−1−15 . 6/5/08 3−1−16 . 6/5/08 3−1−16 . 5/7/09 3−1−19 . 6/5/08 3−1−19 . 6/5/08 3−1−20 . -

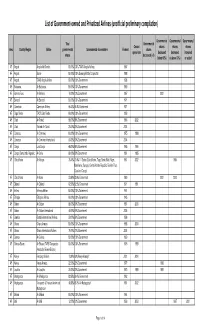

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aerom

Ben Guttery Collection History of Aviation Collection African Airlines Box 1 ADC – Nigeria Aero Contractors Aeromaritime Aeromas African Intl Air Afrique #1 Air Afrique #2 Air Algerie Air Atlas Air Austral Air Botswana Air Brousse Air Cameroon Air Cape Air Carriers Air Djibouti Air Centrafique Air Comores Air Congo Air Gabon Air Gambia Air Ivoire Air Kenya Aviation Airlink Air Lowveld Air Madagascar Air Mahe Air Malawi Air Mali Air Mauritanie Air Mauritius Air Namibia Box 2 Air Rhodesia Air Senegal Air Seychelles Air Tanzania Air Zaire Air Zimbabwe Aircraft Operating Co. Alliances Avex Avia Bechuanaland Natl. Bellview Bop Air Cameroon Airlines Campling Bros. Capital Air Caspair / Caspar Cata Catalina Safari Central African Airways Christowitz Clairways Command Airways Commercial Air Service Copperbelt Court Heli DAS – Dairo Desert Airways Deta DTA Angola East African Airways Corp Eastern Air Zambia Egypt Air Elders Colonial Box 3 Ethiopian Federal Airlines Sudan Flite Star Gambia Airways German Ghana Airways Guinea Hold – Trade Hunting Clan Imperial Inter Air International Air Kitale Zaire Katanga Kenya Airways Lam Lara Leopard Air Lana Lesotho Airways Liverian National Libyan Arab Magnum MISR Namib Air National Nigeria Airways North African Airlines (Tunisia) Phoenix Protea Pyramid RAC – Rhodesia Regie Malgache R.A.N.A Rhodesian Air Service Box 4 Rossair Royal Air Maroc Royal Swazi Ruac Sa Express Safair Safari Air Svcs Saide Sata Algeria SATT Scibe Shorouk Sierra Leone Airlines Skyways Sobelair South African Aerial Transport Somali Airlines -

Preemption of Claims Against an Airline for Parental Child Abduction

"NOT WITHOUT MY DAUGHTER": PREEMPTION OF CLAIMS AGAINST AN AIRLINE FOR PARENTAL CHILD ABDUCTION BARRY S. ALEXANDER* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................... 255 II. TH E CASES........................................ 258 A. PITMAN v. GRAYSON ........................... 259 B. STREETER v. ExECUTVE JET MANAGEMENT, INC.. 261 C. BRADEN v. ALL NIPPON AIRWAYS Co........... 264 D. Ko v. EvA AIRWAYS CoRp. ....................... 265 E. BOWER v. EGYPTArn AIRLINES Co. .............. 267 III. LOOKING FORWARD: PREEMPTION OF CLAIMS ARISING OUT OF PARENTAL CHILD ABDUCTION .............................. 268 A. PREEMPTION UNDER THE ADA ............... 269 1. Background of the ADA...................... 269 2. Provision Having Effect of Law ............... 271 3. Definition of "Service"........................ 272 4. Relation to the "Service" . ................. 274 5. Is There Any Workable Standard That Can Be Applied? .................................... 280 B. PREEMPTION UNDER THE WARSAW/MONTREAL CONVENTION ................................... 282 1. The Convention's Applicability to Claims by Traveling Minors .. ..................... 282 2. The Non-Traveling Parent. ............... 286 3. The Convention Preempts State Law Claims and Precludes Liability Against Air Carriers........ 288 IV. CONCLUSION............................. 289 * Barry S. Alexander is a partner in the New York office of Schnader Harrison Segal & Lewis LLP. He received hisJ.D. from Duke University School of Law and a B.S. from Cornell University. 255 256 JOURNAL OF AIR LAW AND COMMERCE [79 Children who are victims of family abduction are uprooted from their homes and deprived of their other parent. Often they are told the other parent no longer loves them or is dead. Too often abducted children live a life of deception, sometimes under a false name, moving frequently and lacking the stability needed for healthy, emotional development' I.