Air Transport and the Gats

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

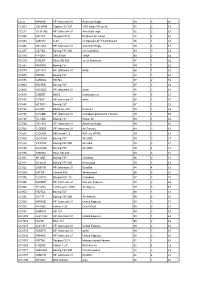

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

Chapter 2 – Aviation Demand Forecast

CHAPTER 2 AVIATION FORECASTS Oscoda – Wurtsmith Airport Authority Oscoda-Wurtsmith Airport Master Plan CHAPTER 2 AVIATION FORECAST Aviation forecasts are time-based projections offering a reasonable expectation of future Oscoda- Wurtsmith Airport activity during the 20-year planning period (2010-2030). Forecasts influence virtually all phases of the planning process, as the relationship between activity and projected demand indicates the type, extent, and timing of Airport improvements for various triggers of Airport infrastructure, equipment and service needs. Primarily, the forecast of aircraft activity is used to quantify the Airport’s operational peaking and capacity characteristics, determine the sizing and space allocation for structures and site development, and form the basis to evaluate the feasibility of various development options. Overall, the forecast predictions attempt to account for factors at Oscoda which could likely influence projections in some significant or substantial way; whether an occurrence of past trends or an assumption of future expectations. As indicated in Chapter 1, the FAA Terminal Area Forecasts (TAF) combined with the forecasts developed for the Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul (MRO) operations continues to support the Boeing 747 heavy widebody aircraft as the Airport’s most demanding, or critical aircraft, used for future facility planning and design purposes. The following forecast components are assessed in this chapter: Aircraft Operations – The number of aircraft landings and takeoffs conducted annually by local and itinerant traffic, including general aviation, commercial and military users. ‘Local’ operations are flights performed in the Airport traffic pattern vicinity, including proficiency training, instrument training and flights from nearby airports. ‘Itinerant’ operations are traffic arriving and departing from beyond the local vicinity. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Schweiz Suisse Svizzera Switzerland VFR Manual

VFR Manual SWITZERLAND VFR 1 Schweiz Suisse Svizzera Switzerland VFR [email protected] Manual TEL: 043 931 61 68 FAX: 043 931 61 59 AFTN: LSSAYOYX AMDT 12/14 AIP Services Effective date: CH-8602 WANGEN BEI DÜBENDORF NOV 13 1 Beiliegende, in der Kontrollliste mit R (Ersatzblatt) oder N (neues Blatt) bezeichnete Blätter, einfügen. Alle in der Kontrollliste mit C (annulliertes Blatt) bezeichneten Blätter entfernen. Insérer les feuillets ci-joints, identifiés dans la liste de contrôle par un R (feuillet de remplacement) ou N (nouveau feuillet). Supprimer les feuillets ci-joints identifiés dans la liste de contrôle par un C (feuillet annulé). Inserire i fogli allegati, contrassegnati sulla lista di controllo con R (foglio di sostituzione) o N (foglio nuovo). Togliere tutti i fogli contrassegnati sulla lista di controllo con C (foglio annullato). Insert the attached sheets, identified in the check list by R (replacement sheet) or N (new sheet). Remove all sheets identified in the check list by C (sheet cancelled). 2 Alle in der Kontrollliste mit S bezeichneten Blätter bedeuten eine SUPPLEMENT-Veröffentlichung (SUP). Tous les feuillets identifiés dans la liste de contrôle par un S signifient une publication SUPPLEMENT (SUP). Tutti i fogli contrassegnati sulla lista di controllo con S significano una pubblicazione SUPPLEMENT (SUP). All sheets identified in the check list by S signify a SUPPLEMENT publication (SUP). 3 Nachtrag auf Seite VFR 7 eintragen. Inscrire l’amendement à la page VFR 7. Annotare l’emendamento alla pagina VFR 7. Record entry of amendment on page VFR 7. 4 AIC: Ins VFR Manual aufgenommen: Insérés dans le VFR Manual: NIL Inseriti nel VFR Manual: Incorporated in VFR Manual: 5 Kontrollliste SUP: Folgende SUP bleiben in Kraft: Liste de contrôle des SUP: Les SUP suivants restent en vigueur: 001/14, 002/14, 004/14, 005/14 Lista di controllo SUP: I seguenti SUP restano in vigore: Checklist SUP: Following SUP are still in force: Alle zur Zeit gültigen SUP-Blätter sind in der CHECK LIST mit S gekennzeichnet. -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Aer Rianta International Recorded a Profit After Tax of €13.2 Million

MAIN EVENTS OF THE YEAR Passenger numbers at Dublin, Shannon and Cork airports increased by 4.3% to 19.3 million – a new record Dublin Airport was one of the fastest growing major airports in Europe and now has over 15 million passengers €96 million was invested by the Group in infrastructure Over 80 airlines served 138 routes. 18 new routes were launched to North America, Continental Europe and the UK Group profit after tax was €36.2 million compared to €11.6 million in 2001, generated on revenues of €421 million Aer Rianta International recorded a profit after tax of €13.2 million An Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern T.D., opened the new terminal extension at Dublin Airport in June Customer service level agreements were developed with airlines and ground handlers at Dublin Airport and a Passenger Services Council was established at the Airport to enhance passenger service standards A major internal re-structuring programme continued including the extensive application of new technologies A €15 million restoration and refurbishment programme was completed at Killarney Great Southern Hotel The 2002 annual report and information on Aer Rianta can be found on our official website www.aerrianta.com Board of Directors 02 Group Structure & Management Team 03 Chairman’s Statement 04 Chief Executive’s Review 12 Review of the Year 16 Airport Management 17 Airport Retailing 22 Aer Rianta International 24 Great Southern Hotels 26 Human Resources 28 1 Ancillary Activities 30 Financial Review 32 Route Network 36 Directors’ Report & Financial Statements 37 Five Year Business Summaries 70 General Business & Aeronautical Information 74 CONTENTS NOEL HANLON Noel Hanlon was first appointed Chairman of the Board in October 1994 and was re-appointed for a second term in October 1999. -

Palm Beach International Airport (PBI)

Agenda Item:~ PALM BEACH COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS AGENDA ITEM SUMMARY -===================================================================== Meeting Date: January 12, 2021 [ ] Consent [ X] Regular [ ] Ordinance [ ] Public Hearing Submitted By: Department of Airports ---------------------------------------------------------------------- I. EXECUTIVE BRIEF Motion and Title: Staff recommends motion to approve: a Contract for Air Service Development Consulting Services (Contract) with Ailevon Pacific Aviation Consulting LLC (Ailevon), a Florida limited liability company, commencing on February 1, 2021, and expiring on January 31, 2024, with one 24-month option to renew for an amount not to exceed $200,000 per contract year for a total not to exceed amount of $600,000 for the initial term. Summary: This Contract provides for professional and technical consulting services on an as-needed basis in support of the air service development program for the Palm Beach International Airport (PBI). Ailevon's principal place of business is Atlanta, GA. Air service development consulting services may include, but are not limited to, air service strategy and planning, airline route study and forecasting, competitive service analysis, business case development for new/expanded air service, development of incentive programs, catchment area demographic and leakage studies and analysis of air traffic demand and airfare data. The Contract provides for a not to exceed amount of $200,000 per contract year with an initial three-year term and an option to renew for an additional 24 months at the County's sole option. Due to lack of availability of qualified Small/Minority/Women Owned Business Enterprises providing the services required by this Contract, the Office of Equal Business Opportunity issued a waiver of Affirmative Procurement Initiatives on July 30, 2020. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

The Undisputed Leader in World Travel CONTENTS

Report & Accounts 1996-97 ...the undisputed leader in world travel CONTENTS Highlights of the year 1 Chairman’s Statement 2 THE NEXT Chief Executive’s Statement 5 Board Members 8 The Board and Board Committees DECADEIN FEBRUARY 1997 and the Report of the Remuneration Committee 10 British Airways celebrated 10 years of privatisation, with a Directors’ Report 14 renewed commitment to stay at the forefront of the industry. Report of the Auditors on Corporate Governance matters 17 Progress during the last decade has been dazzling as the airline Operating and Financial established itself as one of the most profitable in the world. Review of the year 18 Statement of Directors’ responsibilities 25 Report of the Auditors 25 Success has been built on a firm commitment to customer service, cost control and Group profit and loss account 26 the Company’s ability to change with the times and new demands. Balance sheets 27 As the year 2000 approaches, the nature of the industry and Group cash flow statement 28 competition has changed. The aim now is to create a new Statement of total recognised British Airways for the new millennium, to become the undisputed gains and losses 29 leader in world travel. Reconciliation of movements in shareholders’ funds 29 This involves setting a new direction for the Company with a Notes to the accounts 30 new Mission, Values and Goals; introducing new services and Principal investments 54 products; new ways of working; US GAAP information 55 new behaviours; a new approach to The launch of privatisation spelt a Five year summaries 58 service style and a brand new look. -

Aviation Suzanne Pinkerton

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 9-1-1978 Aviation Suzanne Pinkerton Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Recommended Citation Suzanne Pinkerton, Aviation, 10 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 530 (1978) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol10/iss2/11 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAWYER OF THE AMERICAS AVIATION REPORT SUZANNE C. PINKERTON* United Nations In September 1977, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) held its Twenty-second Assembly. Among the resolutions adopted was Resolution A 22-16,1 in which the Assembly requested those member states which had not previously done so, to become parties to the Conven- tion for the Suppression of Unlawful Seizure of Aircraft (Hague, 1970)2 and the Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts against the Safety of Civil Aviation (Montreal, 1971).1 On November 3, 1977, the United Nations General Assembly, in response to the concern voiced by the ICAO, adopted by consensus Resolution 32/84 on the safety of international civil aviation. In adopting the resolution the General Assembly reaffirmed its condemna- tion of aerial hijacking and other interference with civil air travel. Two days earlier the Special Political Commitee had approved, by consensus, the resolution in draft form? In its final form, Resolution 32/8 is divided into five paragraphs. -

Flughafen Information

Flughafen Information Nützliche Informationen für Passagiere mit Linien- und Charterflügen ab und zum Flughafen Bern Einfach. Schnell. Weg. bernairport.ch Check-in Öffnungszeiten Der Terminal öffnet eine Stunde vor dem ersten Flug. Check-in Zeit Linienflug bis 20 Min. Charterflug bis 45 Min. bernairport.ch/check-in Services Bern Airport [email protected] +41 31 960 21 11 Assistance [email protected] +41 31 960 21 31 Lost & Found [email protected] +41 31 960 21 59 Bancomat/Postomat CHF, EUR Autovermietung Avis +41 31 378 15 15 Europcar +41 31 381 75 55 Hertz +41 31 318 21 60 Sixt +41 848 88 44 44 Restaurants Charly’s Check-in +41 31 964 07 50 Gribi’s Eat & Drink +41 31 961 47 47 Polizei und Zoll Polizei +41 31 960 23 11 Zoll +41 31 960 21 15 QUICKLINE-FREE-WLAN Kostenloses WLAN-Internet im gesamten Terminal. Sicherheit: Handgepäck « Druck-/Zippverschluss, durchsichtig « Wiederverschliessbarer Beutel « Max. 1 Liter-Volumen « Bitte separat bei der Kontrolle vorzeigen Der Plastikbeutel muss bei der Sicherheitskontrolle am Flughafen vor- gezeigt werden. Erlaubt sind nur Behälter von Flüssigkeiten, Gels, Crèmes, usw. bis zu einer max. Grösse von 100 ml. Pro Person (Erwachsene, Kinder oder Säuglinge) ist ein Plastikbeutel erlaubt. Unter Auflagen auch in Behältnissen von über 100 ml erlaubt: Für die Reise benötigte Menge an flüssigen Medikamenten sowie Baby- und Spezialnah- rung. Die vorgenannten Flüssigkeiten müssen an der Sicherheitskontroll- stelle vorgewiesen und einer zusätzlichen Kontrolle unterzogen werden. Die Mitnahme auf den Flug ist nur erlaubt, wenn diese vom Sicherheits- personal freigegeben wurden. Im Handgepäck verboten Flüssigkeiten (Gels, Waffen und scharfe Crèmes, Pasten, Gegenstände mit usw.) in Behältnissen Klingenlänge von von mehr als 100 ml mehr als 6 cm Im Reisegepäck verboten Ausnahme Batterien mit einer Eines auf Person Leistung von über getragen erlaubt 160 Wh; Ersatzbat- terien, Powerbanks und E-Zigaretten im Handgepäck mit Einschränkungen Diese Liste ist nicht abschliessend. -

S/C/W/270 18 July 2006 ORGANIZATION (06-3471) Council for Trade in Services

WORLD TRADE RESTRICTED S/C/W/270 18 July 2006 ORGANIZATION (06-3471) Council for Trade in Services SECOND REVIEW OF THE AIR TRANSPORT ANNEX DEVELOPMENTS IN THE AIR TRANSPORT SECTOR (PART ONE) Note by the Secretariat1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES, CHARTS, FIGURES AND APPENDIXES......................................................vi LIST OF ACRONYMS ........................................................................................................................ix INTRODUCTION..................................................................................................................................1 I. AIRCRAFT REPAIR AND MAINTENANCE (MRO).........................................................4 A. ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS .......................................................................................................4 B. REGULATORY DEVELOPMENTS.................................................................................................13 1. Developments concerning the regulation of Maintenance Repair and Overhaul .........13 (a) General evolution ..............................................................................................................13 (b) Maintenance Steering Group (MSG) rules........................................................................13 (c) WTO developments...........................................................................................................13 (d) European Communities .....................................................................................................14