Behaviour of an Incubating Woodcock G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Account

SPOTTED SANDPIPER Actitis macularius non-breeding visitor, vagrant monotypic Spotted Sandpipers breed across n. N America and winter as far south as c. S America (AOU 1998). The status of this species in the Pacific and the Hawaiian Islands is confused by its similarity to Common Sandpiper, a Eurasian counterpart (Dement'ev and Gladkov 1951c, Cramp and Simmons 1983), that has reached the Hawaiian Islands on at least two occasion and possibly others (David 1991). Records of this pair, unidentified to species, have been reported throughout the Pacific (E 41:115, Clapp 1968a, Pyle and Engbring 1985, Pratt et al. 1987) while confirmed Spotted Sandpipers have been recorded from Clipperton, the Marshall, Johnston, and the Hawaiian Is (Amerson and Shelton 1976, Howell et al. 1993, AOU 1998). David (1991) analyzed records of the two species of Actitis sandpipers in the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands and concluded that, between 1975 and 1989, 6 of 12 birds (1983-1989) could be confirmed as Spotted Sandpipers based on descriptions and photographs while the remaining six (1975-1983) could not be identified. Prior to this, Pyle (1977) listed only the species pair (Spotted/Common Sandpiper) for the Hawaiian Islands. Since this analysis and through the 2000s there have been 25 additional records of Actitis, 18 of which we consider confirmed Spotted Sandpipers while 7 did not include enough descriptive notes to separate them from Common Sandpiper. Because 24 of 37 records in the Southeastern Islands have been confirmed as Spotted Sandpipers and only one has been confirmed as a Common Sandpiper, we assume that the following summary of Actitis sandpipers reflects the status of Spotted Sandpiper, the more expected species in the Southeastern Islands. -

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

Actitis Hypoleucos

Actitis hypoleucos -- Linnaeus, 1758 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- CHARADRIIFORMES -- SCOLOPACIDAE Common names: Common Sandpiper; Chevalier guignette European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Van den Bossche, W., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Near Threatened (NT) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence <20,000 km2 combined with a declining or fluctuating range size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of locations or severe fragmentation). The population size is extremely large, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population size criterion (<10,000 mature individuals with a continuing decline estimated to be >10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. In the EU27 the species has undergone moderately rapid declines and is therefore classified as Near Threatened under Criterion A (A2abc+3bc+4abc). Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Ireland, Rep. -

Growth and Development of Long-Billed Curlew Chicks

April 1973] General Notes 435 Pitelka and Donald L. Beaver critically read the manuscript. This work was con- ducted under the I.B.P. Analysis of Ecosystems-TundraProgram and supported by a grant to F. A. Pitelka from the National ScienceFoundation.--THo•rAs W. CUSTrR, Department o! Zoology and Museum o! Vertebrate Zoology, University o! California, Berkeley,California 94720. Accepted9 May 72. Growth and development of Long-billed Curlew chicks.--Compared with the altricial nestlings of passerinesand the semiprecocialyoung of gulls, few studies of the growth and developmentof the precocialchicks of the Charadrii have been made (Pettingill, 1970: 378). In Europe, yon Frisch (1958, 1959) describedthe develop- ment of behavior in 14 plovers and sandpipers. Davis (1943) and Nice (1962) have reported on the growth of Killdeer (Charadriusvociferus), Nice (1962) on the Spotted Sandpiper (Actiris macularia), and Webster (1942) on the growth and development of plumages in the Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani). Pettingill (1936) studiedthe atypical AmericanWoodcock (Philohelaminor). Among the curlews, Genus Numenius, only the Eurasian Curlew (N. arquata) has been studied (von Frisch, 1956). Becauseof the scant knowledgeabout the development of the youngin the Charadriiand the scarcityof informationon all aspectsof the breeding biology of the Long-billed Curlew (N. americanus) (Palmer, 1967), I believe that the following data on the growth and development of Long-billed Curlew chicks are relevant. I took four eggs,one being pipped, from a nest 10 miles west of Brigham City, Box Elder County, Utah, on 24 May 1966. One egg was preservedimmediately for additional study, the others I placed in a 4' X 3' X 2' cardboard box with a 60-watt lamp for warmth in a vacant room in my home until they hatched. -

Ageing and Sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis Hypoleucos

ageing & sexing series Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. 10.18194/ws.00009 This series summarizing current knowledge on ageing and sexing waders is co-ordinated by Włodzimier Meissner (Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdansk, ul. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdansk, Poland, [email protected]). See Wader Study Group Bulletin vol. 113 p. 28 for the Introduction to the series. Part 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos Włodzimierz Meissner 1, Philip K. Holland 2 & Tomasz Cofta 3 1Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdańsk, ul.Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] 232 Southlands, East Grinstead, RH19 4BZ, UK. [email protected] 3Hoene 5A/5, 80-041 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Meissner, W., P.K. Holland & T. Coa. 2015. Ageing and sexing series 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos . Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. Keywords: Common Sandpiper, Actitis hypoleucos , ageing, sexing, moult, plumages The Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos is treated as were validated using about 500 photographs available on monotypic through a breeding range that extends from the Internet and about 50 from WRG KULING ringing Ireland eastwards to Japan. Its main non-breeding area is sites in northern Poland. also vast, reaching from the Canary Islands to Australia with a few also in the British Isles, France, Spain, Portugal MOULT SCHEDULE and the Mediterranean (Cramp & Simmons 1983, del Juveniles and adults leave the breeding grounds as soon Hoyo et al. 1996, Glutz von Blotzheim et al. -

Hatching Dates for Common Sandpiper <I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I

Hatching dates for Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos chicks - variation with place and time T.W. Dougall, P.K. Holland& D.W. Yalden Dougall,T.W., Holland,P.K. & Yalden, D.W. 1995. Hatchingdates for CommonSandpiper Actitishypoleucos chicks - variationwith place and time. WaderStudy Group Bull. 76: 53-55. CommonSandpiper chicks hatched in 1990-94between 24 May (year-day146) and 13 July (year-day196), butthe averagehatch-date was variablebetween years, up to 10 days earlier in 1990 than in 1991. There are indicationsthat on average CommonSandpipers hatch a few days earlierin the Borders,the more northerlysite, butthis may reflecta changein the age structureof the Peak Districtpopulation between the 1970sand the 1980s- 1990s,perhaps the indirectconsequence of the bad weatherof April 1981. Dougall,T. W., 29 LaudstonGardens, Edinburgh EH3 9HJ, UK. Holland,P. K., 2 Rennie Court,Brettargh Drive, LancasterLA 1 5BN, UK. Yalden,D. W., Schoolof BiologicalSciences, University, Manchester M13 9PT, UK. INTRODUCTION Yalden(1991a) in calculatingthe originalregression, and comingfrom the years 1977-1989 (mostlythe 1980s). CommonSandpipers Actitis hypoleucos have a short We also have, for comparison,the knownhatch dates for breedingseason, like mostwaders; arriving back from 49 nestsreported by Hollandet al. (1982), comingfrom West Africa in late April, most have laid eggs by mid-May, various sites in the Peak District in the 1970s. which hatch around mid-June. Chicksfledge by early July, and by mid-Julymost breedingterritories are Ringingactivities continue through the breedingseason at deserted(Holland et al. 1982). The timingof the breeding both sites, and chickscan be at any age from 0 to 19 days season seems constantfrom year to year, but there are old when caught (thoughyoung chicks are generally few data to quantifythis impression.It is difficultto locate easier to find). -

Review of the Conflict Between Migratory Birds and Electricity Power Grids in the African-Eurasian Region

CMS CONVENTION ON Distribution: General MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/Inf.10.38/ Rev.1 SPECIES 11 November 2011 Original: English TENTH MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Bergen, 20-25 November 2011 Agenda Item 19 REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION (Prepared by Bureau Waardenburg for AEWA and CMS) Pursuant to the recommendation of the 37 th Meeting of the Standing Committee, the AEWA and CMS Secretariats commissioned Bureau Waardenburg to undertake a review of the conflict between migratory birds and electricity power grids in the African-Eurasian region, as well as of available mitigation measures and their effectiveness. Their report is presented in this information document and an executive summary is also provided as document UNEP/CMS/Conf.10.29. A Resolution on power lines and migratory birds is also tabled for COP as UNEP/CMS/Resolution10.11. For reasons of economy, documents are printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. The Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) REVIEW OF THE CONFLICT BETWEEN MIGRATORY BIRDS AND ELECTRICITY POWER GRIDS IN THE AFRICAN-EURASIAN REGION Funded by AEWA’s cooperation-partner, RWE RR NSG, which has developed the method for fitting bird protection markings to overhead lines by helicopter. Produced by Bureau Waardenburg Boere Conservation Consultancy STRIX Ambiente e Inovação Endangered Wildlife Trust – Wildlife & Energy Program Compiled by: Hein Prinsen 1, Gerard Boere 2, Nadine Píres 3 & Jon Smallie 4. -

Migration Timing, Routes, and Connectivity of Eurasian Woodcock Wintering in Britain and Ireland

Migration Timing, Routes, and Connectivity of Eurasian Woodcock Wintering in Britain and Ireland ANDREW N. HOODLESS,1 Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Burgate Manor, Fordingbridge, Hampshire SP6 1EF, UK CHRISTOPHER J. HEWARD, Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust, Burgate Manor, Fordingbridge, Hampshire SP6 1EF, UK ABSTRACT Migration represents a critical time in the annual cycle of Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola), with poten- tial consequences for individual fitness and survival. In October–December, Eurasian woodcock migrate from breeding grounds in northern Eurasia over thousands of kilometres to western Europe, returning in March–May. The species is widely hunted in Europe, with 2.3–3.5 million individuals shot per year; hence, an understanding of the timing of migra- tion and routes taken is an essential part of developing sustainable flyway management. Our aims were to determine the timing and migration routes of Eurasian woodcock wintering in Britain and Ireland, and to assess the degree of connec- tivity between breeding and wintering sites. We present data from 52 Eurasian woodcock fitted with satellite tags in late winter 2012–2016, which indicate that the timing of spring departure varied annually and was positively correlated with temperature, with a mean departure date of 26 March (± 1.4 days SE). Spring migration distances averaged 2,851 ± 165 km (SE), with individuals typically making 5 stopovers. The majority of our sample of tagged Eurasian woodcock migrated to breeding sites in northwestern Russia (54%), with smaller proportions breeding in Denmark, Scandinavia, and Finland (29%); Poland, Latvia, and Belarus (9.5%); and central Russia (7.5%). The accumulated migration routes of tagged individ- uals suggest a main flyway for Eurasian woodcock wintering in Britain and Ireland through Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, and then dividing to pass through the countries immediately north and south of the Baltic Sea. -

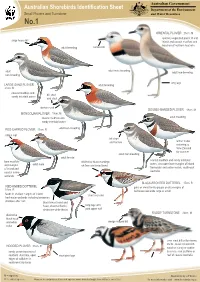

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

202 Common Redshank Put Your Logo Here

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here Put your logo here 202 Common Redshank Ruff Redshank. Spring. Adult (02-V) COMMON REDSHANK (Tringa totanus ) SEXING IDENTIFICATION Plumage of both sexes alike. 27-28 cm. In spring with brownish upperparts barred dark; white rump; white tail with dark bars; wings with a broad white band on the ed- AGEING ge; white underparts with dark streaks on head, This species is a scarce breeder in Aragon, so neck and breast; red bill with dark tip; orange- only 3 age classes can be recognized: red legs. In autumn with darker colours on up- 1st year autumn with fresh plumage; median perparts: grey tinge on breast. coverts spotted pale on edge; tertials brown with buff and dark marks; pointed tail feathers; breast slightly streaked; dull reddish base of bill; yellowish legs. 2nd year spring similar to adult ; this age can be recognized only in birds with some unmoul- ted median wing coverts and/or tertials; flight feathers moderately worn. Adult with median coverts with whitish edge and dark subterminal band; tertials grey brown with variable markings: either plain or with dark sepia bars, sometimes with extensive dark markings; rounded tail feathers; underparts with variable amount of dark barring and spot- ting; reddish legs and base of bill. Redshank . Pattern of wing, tail and bill. SIMILAR SPECIES Recalls a Spotted Redhsank in autumn , without a white patch on wings and has a longer bill; Redshank. Ruff has a narrower wing band and two whi- Ageing. te bands on sides of uppertail Pattern of bill: top adult; bot- Spotted tom 1st Redshank. -

Green Sandpiper

Green Sandpiper The Green Sandpiper (Tringa ochropus) is a small wader of the Old World. The genus name Tringa is the New Latin name given to the Green Sandpiper by Aldrovandus in 1599 based on Ancient Greek trungas, a thrush-sized, white- rumped, tail-bobbing wading bird mentioned by Aristotle. The specific ochropus is from Ancient Greek okhros, "ochre", and pous, "foot". The Green Sandpiper represents an ancient lineage of the genus Tringa and its only close living relative is the Solitary Sandpiper (T. solitaria). They both have brown wings with little light dots and a delicate but contrasting neck and chest pattern. In addition, both species nest in trees, unlike most other scolopacids. Given its basal position in Tringa, it is fairly unsurprising that suspected cases of hybridisation between this species and the Common Sandpiper (A. hypoleucos) of the sister genus Actitis have been reported. This species is a somewhat plump wader with a dark greenish-brown back and wings, greyish head and breast and otherwise white underparts. The back is spotted white to varying extents, being maximal in the breeding adult, and less in winter and young birds. The legs and short bill are both dark green. It is conspicuous and characteristically patterned in flight, with the wings dark above and below and a brilliant white rump. The latter feature reliably distinguishes it from the slightly smaller but otherwise very similar Solitary Sandpiper (T. solitaria) of North America. It breeds across subarctic Europe and Asia and is a migratory bird, wintering in southern Europe, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and tropical Africa. -

Tringa Melanoleuca (Greater Yellowlegs)

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Tringa melanoleuca (Greater Yellowlegs) Priority 3 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Considered stable range wide, considered species of low or moderate concern by US Shorebird Conservation Plan however due to vulnerability to climate change considered priority 3. Listed as "Species of Least Concern" by U. S. Shorebird Conservation Plan Partnership - 2015. Species Conservation Range Maps for Greater Yellowlegs: Town Map: Tringa melanoleuca_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Tringa melanoleuca_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: NA Regional Endemic: NA High Regional Conservation Priority: NA High Climate Change Vulnerability: Vulnerability: 3, Confidence: Medium, Reviewers: Decided in Workshop (W) Understudied rare taxa: NA Historical: NA Culturally Significant: NA Habitats Assigned to Greater Yellowlegs: Formation Name Cliff & Rock Macrogroup Name Rocky Coast Formation Name Freshwater Marsh Macrogroup Name Emergent Marsh Macrogroup Name Modified-Managed Marsh Formation Name Intertidal Macrogroup Name Intertidal Gravel Shore Macrogroup Name Intertidal Mudflat Macrogroup Name Intertidal Sandy Shore Stressors Assigned to Greater Yellowlegs: