Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emile Zola Chair for Interdisciplinary Human Rights Dialogue Will Strive to Strengthen the Human Rights Ethos, Values and Forces in the Israeli Society

VISION The Emile Zola Chair for Interdisciplinary Human Rights Dialogue will strive to strengthen the human rights ethos, values and forces in the Israeli society. It will do so through interdisciplinary educational, cultural and research activities; dissemination of relevant information, support for and cooperation with NGOs committed to human rights and existing human rights centers in Israeli academic institutions, and the encouragement of individuals whose work for human rights is exemplary, in Israel. The Chair honors the legacy of Emile Zola. Emile Zola was a fiction writer. It is not, however, for his artistic endeavors but for his humanistic stand; his ability to "speak truth to power" when that truth had few friends; his willingness to pay a personal price (which included loss of membership otherwise granted at the much coveted Academie Française; a criminal trial, conviction and exile) that he is remembered. This stand, and "the March for Truth" that he initiated with his J'Accuse had an enormous impact in terms of both democracy (the real winners of the "Dreyfus Affair" – the happy end of which put to rest the ancient regime – are democratic governance and the values of freedom of speech, free press and humanity). In a sense, the essential ethos of what does it mean to be a person committed to humanity and human rights, of the impact a person can have and of the wider significance of that impact, can be taught through this story. Establishing the Emile Zola Chair for Human Rights not only reflects a moral duty and pays a debt of honor, it also serves as a reminder, a model and a sign of hope: it is to remind the Israeli society that the national enterprise need not be carried out at the expense of a humanistic commitment to marginalized communities; that its very existence has been thus nourished. -

Final Report 240210

Towards A Strategy for Culture in the Mediterranean Region EC Preparatory document Needs and opportunities assessment report in the field of cultural policy and dialogue in the Mediterranean Region A study1 prepared for the European Commission by Fanny Bouquerel and Basma El Husseiny November 2009 1 Diclaimer: This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Basma El Husseiny and Fanny Bouquerel for the society Berenschot and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union 1 Acknowledgements The experts would like to thank all the interviewees who gave their time to answer the questionnaires. 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 5 2. Executive Summary .................................................................................... 12 Context...................................................................................................................13 A Consultative Process ..........................................................................................16 1. Cultural Policy and Capacity of the Cultural Sector in the South Med Region ...................................................................................................................................17 1.1 Cultural Policies ...............................................................................................17 1.2 Capacity of the Cultural -

8Th Festival International New Drama 6 – 9 November 2008 | Focus Palestine

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// F.I.N.D. 8 Zeit.Genossen * F.I.N.D. 8 8th Festival International New Drama 6 – 9 November 2008 | Focus Palestine * sirtu ’atamanna: lau ’anni: nabata! »Sometimes I’d rather be a plant« from »No, he is not dead« by Hussein Barghouti /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////1 F.I.N.D. 8 //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Welcome! After the focus of last year’s festival on Israeli theater, the current 8th Alongside the readings in German, two guest performances will afford Festival of International New Drama (F.I.N.D.) returns once again to the Berlin audiences the rare experience of hearing the Arabic language on Levant, that coastland from which Zeus – in mythic times and in the stage. »In Spitting Distance« by Taher Najib, and »A Memory of Forget- shape of a bull – abducted the princess Europa and took her to the fulness« by Mahmoud Darwish are two internationally regarded theatri- West. The consequences of that act are well known: her brother Kad- cal productions which take on the question of Palestinian identity. mos followed her, brought writing to Greece and became the forebear »Ramallah’s Lions« is a short performance by Wafa Hourani on daily life of Oedipus, whose fate inspired one of the most important dramas of in Ramallah under the second Intifada, which is presented with three world literature. actors from the Schaubühne. Wajdi Mouawad, a French-Canadian playwright from Beirut, has traced A further focal point of the festival is the three pieces from Scandinavia these complicated family histories between the Near East and the which are based on documentary material. -

The Performative Utterance “I” Theatricality and Subversion of Identity in the Works of Eyal Weiser Sharon Aronson-Lehavi

The Performative Utterance “I” Theatricality and Subversion of Identity in the Works of Eyal Weiser Sharon Aronson-Lehavi Eyal Weiser is an Israeli playwright and theatre director whose works complexly interrogate and explore constructions of Israeli identity, first and foremost by addressing Israeli identity/(ies) as constructions. His works thus offer a critique of historical, social, and cultural processes that were (and are) intended to instigate and naturalize an idea of a collective Jewish-Israeli identity. By unmasking identity as a construction — as a result of ideological, educational, and political mechanisms — Weiser’s works destabilize the borders between lies and truth, fiction and real- ity, and fabrication and authenticity. Over the past decade, Weiser has emerged as a significant Sharon Aronson-Lehavi is Chair of the Department of Theatre Arts at Tel Aviv University and Academic Director of the TAU Theatre. She is the author of Street Scenes: Late Medieval Acting and Performance (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) and Gender and Feminism in Modern Theatre (Open University Press, in Hebrew, 2013), editor of Wanderers and Other Israeli Plays (Seagull Books, In Performance series, 2009), and coeditor with Atay Citron and David Zerbib of Performance Studies in Motion: International Perspectives and Practices in the Twenty-First Century (Bloomsbury, 2015). TDR: The Drama Review 61:4 (T236) Winter 2017. ©2017 22 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00690 -

Josef Sprinzak – Voice, Sound and (Visual) Performance Art Curriculum Vita

Josef Sprinzak – Voice, Sound and (Visual) Performance Art Curriculum Vita Born 1962 Lives and works from Tel-Aviv Contact Information Mail: Mr. Josef Sprinzak, Daphna 24/4, Tel-Aviv 6492922, Israel E-Mail: [email protected] Tel: +972-54-8128768 Education 2013-2014 Hebrew University in Jerusalem, School of Arts, Post Doctoral Research. 2003-2011 University of Ben-Gurion in the Negev, PhD. in Theory of Art. 1990-1993 The School of Visual Theater, Jerusalem, Theater and Performance Art. 1988-1990 Hebrew University, Jerusalem M.Sc. in Computer Science. 1984-1986 Hebrew University, Jerusalem B.Sc. in Computer Science. Selected Performances, Venues and Projects 2014 – “The Replacement”, Performance action in the Israeli Art exhibition, part of “ECHO: VOICE MUSEUM ACTION” in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Curator: Danna Heller. 2014 – “The Shining – A Live Sound Play for Speaking Lights”, Live audio- visual Performance, “Dybbuk” event in “Mamuta” Center for Art and Media, Jerusalem, Curators: Salamanca and Guy Biran. 2014 – “Map Song”, Sound performance, “Borderline” event in “Mamuta” Center for Art and Media, Jerusalem, Curators: Salamanca. 2013 – “Jerusalem Wordscape (at night)”, Sound Installation, Notre Dame Center in Jerusalem, “Iconophilia” event. Curators: Lea Abir and Smadar Keren. 2012 - “What my grandmother said to Franz Josef”, Performance and Sound Installation, international group exhibition “Galicia, Mon Amour”, BWA Sokol Art Gallery, Nowy Sacz, Poland, Curator: Danna Heller. 2011 – "Bedtime Stories and Lullabies", Performance project in front of children in rural villages in northern Portugal, "Vozes de Magaio" Project organized by Binarual, Portugal, Curator: Luis Costa. 2011 – Sound Installation based on radio play "Many Said Yes", Bat-Yam Museum of Art, in group exhibition "Schooling", Curators: Tali Tamir, Meir Tati. -

F.I.N.D. 2011 – Festival of International New Drama

F. I.N. D. 2011 3-13 March 2011 Festival of International New Drama Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz > F.I.N.D. 2011 – Festival of International New Drama Herzlich willkommen! Welcome! Bienvenue! Добро пожаловать! !Tervetuloa نيلرب يف ًالهسو ًالهأ !Bienvenidos¡ ברוכים הבאים With F.I.N.D. 2011 the Schaubühne continues an important tradition My sincere thanks to the organisers at the Schaubühne and to all of inviting theatre directors from all over the world to Berlin and pro - the sponsors who help make this festival such an invaluable asset viding us with insights into their current work. to theatre. Over the years, not only has an international network evolved, but Berlin welcomes all participants of the 11th Festival of International also the basis for continuing fruitful exchange has been established. New Drama. We wish them a memorable stay in Berlin, a productive The Berlin public has a wonderful opportunity to experience the latest festival with many inspiring, theatrical experiences and exciting en - plays and productions from the international theatre community and to counters. meet eminent artists first-hand. This year there is also an important ad - ditional element: with »F.I.N.D. plus«, the festival has created a platform Klaus Wowereit where young professionals can meet and work with experienced theatre Governing Mayor of Berlin, patron of F.I.N.D. 2011 professionals. ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Over the past ten years, the Festival of International New Drama With »F.I.N.D. plus« the Schaubühne is taking a stand against the usual has become indispensable for anyone in Berlin who wants to en - performance stress and lack of contact which characterise many other gage with the most important practitioners of international theatre. -

Encyclopedia of Invisible, Unknown and Ghostly Knowledge Produced by BLACKMARKET for USEFUL KNOWLEDGE and NON-KNOWLEDGE NO 12

Encyclopedia of invisible, unknown and ghostly knowledge produced by BLACKMARKET FOR USEFUL KNOWLEDGE AND NON-KNOWLEDGE NO 12 The Blackmarket knowledge is offered in the following languages: Arabic, English, French, German, Hebrew, Italian, Polish INVISIBLE KNOWLEDGE Communication Gadi Algazi was born in Tel Aviv in 1961. He is an associate professor at the Department of History, Tel Aviv University, and senior editor of the journal “History & Memory.” He is also a member of the editorial board of the journals “Past & Present” and “Historische Anthropologie”. In 1980, during his military service, he refused to serve in the occupied territories and was sentenced to one year in jail. He lives in Tel-Aviv with his three children. (Heb.) “And Thou shall tell your son” - On Oral History in Palestinian Society Yigal Halfin is a senior lecturer at the Department of History, Tel-Aviv University, specializing in the history of modern Russia in general, and Stalinism in particular. His research deals with testimonies, confessions and interrogation documents that are stored in the Russian archives, open to the public only since the early 90s, following the fall of the Soviet Union. He has published many books, among them “The Stalinist Purges” (Resling). In the past, Halfin lead workshops on how to steal books. (Eng., Heb., Rus.) On the Party’s Sofa - Bolshevik Confessions in Light of Christianity and Psychoanalysis Ethics Yechiel Bar Ilan is a senior lecturer at the Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, and internal medicine specialist. He teaches medical ethics and philosophy, and is head of Meir Hospital Ethics Forum. He publishes on human rights, bioethics, art & medicine, and collects paintings and images with medical themes, especially the figure of the doctor. -

International& Europe

PLAYSVol 31 Nos 4 - 6 £8.90 / €12.90 / $15.90 ISSN 0268 2028 SUMMER 2016 INTERNATIONAL & EUROPE Thinking Beyond National Borders Israeli director Ofira Henig interviewed by Doron Elia P52 Theatre in Palestine Karma Zoabi P56 The 2016 Europe Theatre Prize, a report Sergio Lo Gatto P36 PLUS The Pacific Playwrights UK, EUROPE, CHINA, Festival NORTH AMERICA, Robert Cohen P72 AUSTRALIA UK Drama Schools REPORTS, PICTURES Jeremy Malies P10 & LISTINGS CONTENTS 4 London Preview Peter Roberts 5 What’s On In London Features 10 UK Drama Schools Jeremy Malies LONDON 12 Neil Dowden at Shakespeare’s Globe 14 Neil Dowden at The Threepenny UK Drama Schools, a report Opera by Jeremy Malies 16 Christine Eccles at Les Blancs; People, Places & Things and With applicant-to-place ratios of at least 7:1, Blue/Orange being accepted at a major drama school in 18 John Russell Taylor at The Flick the UK is harder than winning a place at and The Suicide Oxford or Cambridge Universities. Full 20 John Russell Taylor at Dr Faustus and Stone Face scholarships are rare, and after three years of 22 Jeremy Malies at The Truth study graduates can be left in debt to the 24 Peter Roberts at the English tune of £40,000 as they struggle in a National Opera notoriously competitive sector. Is formal UK REGIONS study worth the sacrifices? How much 26 Crysse Morrison in the Southwest support do drama schools provide to 28 Jeremy Malies in the Southeast students during their first few years in the 30 Basil Abbott in East Anglia industry? Who are the leading providers of 32 Nick Ahad -

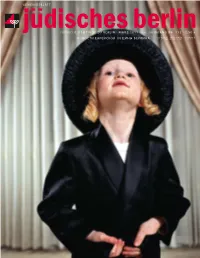

Gemeindeblatt Новости Еврейской Общины

GEMEINDEBLATT JÜDISCHE GEMEINDE ZU BERLIN · MÄRZ 2011 · 14. JAHRGANG NR. 132 · 2,50 € НОВОСТИ ЕВРЕЙСКОЙ ОБЩИНЫ БЕРЛИНА Die Jüdische Gemeinde zu Berlin und Bambinim laden ein zu Wir laden herzlich ein PURIM IN DER zur Purim-Feier der Synagoge Oranienburger Straße FAMILIE am Sonntag, 20. März 2011 im Großen Saal der Oranienburger Straße. So 20. März 16 – 18 Uhr Kleiner Saal im Gemeindehaus 10 Uhr Schacharit-Gebet Fasanenstraße 79 – 80 ca. 11.30 Uhr Megilla-Lesung 10623 Berlin 16 – 17 Uhr Im Anschluss Kostümschau und essen wir gemeinsam Suppe, Gesichter anmalen Hamantaschen und die von Euch Basteln der besten mitgebrachten Salate. Krachmacher Tanzen Gegen 13 Uhr beginnt ein 17 – 17.45 Uhr Purim-Maskentheater Für die Kinder: mit Ariella Hirshfeld und Ingrid eine musikalische Purimgeschichte Braun. Optional für die Eltern: Vortrag mit Rabbiner Tovia Ben Chorin zum Thema »Rachegefühle im Judentum« Kommt und lasst uns 17.45 – 18 Uhr zusammen feiern! Buffet für alle mit Hamantaschen und Früchten Wir freuen uns auf Eure Kostüme! Für Kinder im Alter von 3–6 Jahren + deren Eltern Rückfragen bitte an Dalit Mann, Eintritt: 1 Kind + 1 Erwachsener = 8 €, jede zusätzliche Person 2 € [email protected] Anmeldung über [email protected] oder T. 530 975 85 (begrenzte Teilnehmerzahl!) oder 030-88028-253 INHALT · СОДЕРЖАНИЕ Inhalt Содержание jüdisches berlin Gemeindeblatt 4 | Liebe Gemeindemitglieder! 4 | Дорогие члены Общины! V.i.S.d.P. 5 Religion 5 Религия Präsidium der Repräsentantenver- 5 | Rabbinerin Gesa Ederberg über 6 | Раввин Геза