Social Work Promoting Community and Environmental Sustainability: a Workbook for Global Social Workers and Educators (Volume 2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BICYCLE RING in AARHUS, DENMARK: a Case Study of Maintaining People Friendly Environments While Managing Cycling Growth

THE BICYCLE RING IN AARHUS, DENMARK: a case study of maintaining people friendly environments while managing cycling growth Urban Planning & Management | Master Thesis | Aalborg University | June 2017 Estella Johanna Hollander & Matilda Kristina Porsö Title: The Bicycle Ring in Aarhus, Denmark: a case study of maintaining people friendly environments while managing cycling growth Study: M.Sc. in UrBan Planning and Management, School of Architecture, Design and Planning, AalBorg University Project period: FeBruary to June 2017 Authors: Estella Johanna Hollander and Matilda Kristina Porsö Supervisor: Gunvor RiBer Larsen Pages: 111 pages Appendices: 29 pages (A-E) i Abstract This research project seeks to analyze the relationship Between cycling and people friendly environments, specifically focusing on the growth in cycling numbers and the associated challenges. To exemplify this relationship, this research project uses a case study of the Bicycle Ring (Cykelringen) in Aarhus, Denmark. Four corners around the Bicycle Ring, with different characteristics in the Built environment, are explored further. In cities with a growing population, such as Aarhus, moBility is an important focus because the amount of travel will increase, putting a higher pressure on the existing infrastructure. In Aarhus, cycling is used as a tool to facilitate the future demand of travel and to overcome the negative externalities associated with car travel. The outcome of improved mobility and accessibility is seen as complementary to a good city life in puBlic spaces. Therefore, it is argued that cycling is a tool to facilitate people friendly environments. Recently, the City of Aarhus has implemented cycle streets around the Bicycle Ring as a solution to improve the conditions around the ring. -

Student Handbook for Students at Vejlby Table of Contents

Student handbook for students at Vejlby Table of contents Welcome . .5 Contacts of the programme . 6. The administration . .7 Student counselling . 8. International Office . .8 Career Centre . .9 The library . 9. The daily timetable . .10 Pedadogical principles . 10. Excursions . 12. Internet and computers . .12 Photo copying . .13 How to stay up-dated . 15. Danish language courses . 15. Leisure facilities . .16 Campus activities . .16 Students’ bar: “Drænrøret” (“The Drainage”) . .16 “Spiserøret” (“The oesophagus”) . .16 The Risskov area . .16 Downtown Aarhus . .17 Alcohol and drugs . .17 InterCultureClub . .17 Food . .17 Washing . .18 Parking . .18 Getting here by bus, bicycle or taxi . .18 2 How to pay . .21 Post . 21. Doctors, hospitals and pharmacies . .22 Rules and regulations . .24 General house rules . .24 Fire regulations . .25 3 4 Welcome On behalf of all of the staff at Business Academy Aarhus, Vejlby Department, I would like to welcome you as a student . We will do our very best to fulfil your expectations and give you a good foundation for your future career . In addition to the English taught AP degree in Environmental Management, we offer a Danish taught AP degree at Vejlby Department . We also offer a top-up bachelor’s degree in both Danish and English, and finally we educate Danish farmers . We offer accommodation for all our farmer students as well as for a number of the Danish and international AP degree students . The guide is intended to help you during your stay in Denmark . It will give you some practical advice and information on your first acquaintance with Denmark and the college . -

Argentina Buenos Aires Universidad

COUNTRY CITY UNIVERSITY Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa (UADE) Buenos Aires Argentina Buenos Aires Universidad del Salvador (USAL) Australia Brisbane Queensland University of Technology Australia Brisbane Queensland University of Technology QUT Australia Brisbane University of Queensland Australia Joondalup Edith Cowan University, ECU International Australia Melboure Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) Australia Perth Curtin University Australia Toowoomba University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba Australië Newcastle Newcastle university Austria Dornbirn FH VORARLBERG University of Applied Sciences Austria Graz FH Joanneum University of applied sciences Austria Innsbruck FHG-Zentrum fur Gesundheitsberufe Tirol GmbH Austria Linz University of Education in Upper Austria Austria Vienna Fachhochschule Wien Austria Vienna FH Camus Wien Austria Vienna University of Applied Sciences of BFI Vienna Austria Vienna University of Applied Sciences WKW Vienna Belgium Antwerp AP University College Belgium Antwerp Artesis Plantijn Hogeschool van de Provincie Antwerpen Belgium Antwerp De Universiteit van Antwerpen Belgium Antwerp Karel de Grote Hogeschool, Antwerp Belgium Antwerp Karel de Grote University College Belgium Antwerp Plantijn Hogeschool Belgium Antwerp Thomas More Belgium Antwerp University of Antwerp Belgium Brugges Vives University College Belgium Brussel LUCA School of Arts Belgium Brussel Hogeschool Universiteit Brussel Belgium Brussels Erasmushogeschool Brussel Belgium Brussels ICHEC Bruxelles Belgium Brussels -

DIAKON Bladet Diakonforbundet2 Diakonbladet Filadelfi a Og Marts 2015 Diakonhøjskolens Diakonforbund Kan Det Betale Sig?

VELKOMMEN 1 MARTS 2015 TEOLOGI 52. ÅRGANG RELIGIONSVIDENSKAB DIAKON bladet Diakonforbundet2 DIAKONbladet Filadelfi a og Marts 2015 Diakonhøjskolens Diakonforbund Kan det betale sig? www.diakonforbund.dk DIAKONBLADETS REDAKTIONSGRUPPE En tidligere minister blev kendt for at lancere Indlæg til Diakonbladet sendes til ansvarshavende redaktør: Diakon, sognemedhjælper Hanne Raabjerg, Fastrupvej 6, 8355 Solbjerg. sloganet ”Fra forskning til faktura”. Meningen var Tlf. 4124 5542 • E-mail: [email protected] klar nok: Det offentliges investering i uddannel- Diakon Rita Lund Mathiasen, Brunevang 86, 2., 2610 Rødovre serne skal kunne betale sig. Det skal underlægges Tlf. 5826 1147 • E-mail: [email protected] Diakon/diakonsekretær Conny Pedersen Hjelm det krav, at de bidrager til samfundets produkti- Center for diakoni og ledelse, Kolonivej 19, Filadelia, 4293 Dianalund on, og det skal uddannelserne indrettes efter. Tlf. 5827 1252 • E-mail: [email protected] Den holdning er trængt ned gennem hele ud- Diakon Britt Hoffmann, Pramdragervej 12, 8940 Randers SV. Tlf. 4129 0278 • E-mail: [email protected] dannelsessystemet lige fra de videregående ud- Diakon, diakonsekretær Bent Ulrikkeholm, Studsgade 44, 8000 Aarhus C. (arb.) dannelser til folkeskolen, men det har også fået Tlf. 2028 1381 • E-mail: [email protected] indlydelse på, hvordan vi ser på samfundets sva- DIAKONFORBUNDET FILADELFIA geste og de handicappede. Formand: Kirsten Nørremark Jensen, Tylvadvej 16, 6900 Skjern Det er nu fastslået, at forældre til handicap- Tlf. 4081 7427 • E-mail: [email protected] pede børn på døgninstitutioner skal pålægges Diakonisekretær: Conny Hjelm, Kolonivej 19, 4393 Dianalund. Tlf. 5827 1255 • E-mail: [email protected] egenbetaling til kommunen for opholdet, hvis DIAKONHØJSKOLENS DIAKONFORBUND anbringelsen ikke har ”et udpræget behandlings- Formand: Diakon Birthe Fredsgaard, Harrestrupvej 4 mæssigt sigte”, med andre ord: hvis man ikke in- 7500 Holstebro Tlf. -

VIA IT & Digitalisering, ITS Og DMJX

VIA IT & Digitalisering, ITS og DMJX Erfaringer og overvejelser ifbm. forberedelse til hel eller delvis outsourcing af it-drift Mads Konge Nielsen, chef for IT & Digitalisering Spørgsmål • Hvor mange er med i et driftsfællesskab i dag? • Hvor mange driftsfællesskaber er der tilstede? ITS, hvad er det? Et såkaldt administrativt servicefællesskab. • Idéen er, at man går sammen om at løse opgaver. Andelsforening (shared services) • IKKE ET KUNDE/LEVERANDØR FORHOLD! Og • Et udtryk for markedsgørelse indenfor det offentlige. Ambitionen er at overføre den private sektors dynamik ved at skabe flere tilbud. Hvad er et administrativt fællesskab eller shared service center(SSC)? En del af VIA • VIA er værtsinstitution for ITS og DMJX Om VIA: • DK’s 3. største uddannelsesinstitution. • Ca. 40 mellemlange uddannelser – lærer – ingeniør – sygeplejerske – pædagog osv. • Siden 2000 Hvem er IT-Supportcentret (ITS) • Oprindeligt fra Århus Amt • Oprindelig idé: Et teknisk Egå Gymnasium Grenaa Gymnasium supportcenter, som gjorde Langkær Gymnasium det muligt for skoler at Marselisborg Gymnasium koncentrere sig om Odder Gymnasium kerneopgaven – Paderup Gymnasium undervisning og Randers HF & VUC administration. Randers Social- og Sundhedsskole Risskov Gymnasium Social- og Sundhedsskolen i Silkeborg Social- og Sundhedsskolen Skive, Thisted, Viborg Støvring Gymnasium Vesthimmerlands Gymnasium og HF Tal Viby Gymnasium VUC Djursland IT i ITS og VIA: Aalborg Katedralskole 80 medarbejdere Aarhus Katedralskole 60.000 brugere Århus Statsgymnasium Århus Akademi 10.000 -

OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation OECD Reviews of Regional Central and Southern Denmark

OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation Regional of Reviews OECD Central and Southern Denmark Contents OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation Assessment and recommendations Introduction Central Chapter 1. Innovation and the economies of Central and Southern Denmark Chapter 2. Danish governance and policy context for regional strategies and Southern Denmark I Chapter 3. Regional strategies for innovation-driven growth nnovation C e nt r al an al d So uth er n D n Please cite this publication as: e OECD (2012), OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation: Central and Southern Denmark 2012, nma OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264178748-en r k This work is published on the OECD iLibrary, which gathers all OECD books, periodicals and statistical databases. Visit www.oecd-ilibrary.org, and do not hesitate to contact us for more information. isbn 978-92-64-17873-1 04 2012 09 1 P -:HSTCQE=V\]\XV: 042012091.indd 1 08-Aug-2012 2:19:29 PM OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation: Central and Southern Denmark 2012 This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Please cite this publication as: OECD (2012), OECD Reviews of Regional Innovation: Central and Southern Denmark 2012, OECD Publishing. -

Erhvervsuddannelser Og Erhvervsgymnasier

Åbent hus / virtuelle arrangementer / Aarhus / januar 2021 Erhvervsuddannelser og Erhvervsgymnasier På Jordbrugets UddannelsesCenter Århus kan du komme til uddannelsesmesse den 28. januar 2021. Det er også muligt at komme til rundvisning på skolen og at få en individuel snak med en studievejleder. Jordbrugets UddannelsesCenter Århus tilbyder: • EUD (Erhvervsuddannelser) inden for gartner, anlægsgartner, landmand, dyrepasser og skov- og naturtekniker • EUX grundforløb (Den erhvervsfaglige studentereksamen) • EUD10 (Erhvervsrettet 10. klasse) Studievejlederne står klar til at tage imod jer. Book en plads på uddannelsesmessen eller en rundvisning - eller kontakt en studievejleder for en telefonisk eller virtuel vejledningssamtale her: https://xn-- besguddannelserne-20b.dk/jordbrugets-uddannelsescenter/ SOSU Østjylland tilbyder virtuel eller fysisk rundvisning på skolen (naturligvis under hensyn til Covid-19 restriktioner). Til rundvisning vil enten en elev eller vejleder vise skolens spændende og anderledes undervisnings- og øvelokaler frem, og fortælle om vores uddannelser. De er selvfølgelig også klar til at svare på spørgsmål. På SOSU Østjylland har vi uddannelserne: • SOSU Assistent • SOSU Hjælper • Pædagogisk Assistent • EUX Velfærd (Den erhvervsfaglige studentereksamen) • EUD10 (Erhvervsrettet 10. klasse) Book virtuel eller fysisk rundvisning på SOSU Østjylland her: https://xn--besguddannelserne-20b.dk/sosu- ostjylland/ På Aarhus Business College/Aarhus Handelsgymnasium kan I booke jeres eget åbent hus – enten i form af rundvisning -

Welcome Future

WELCOME FUTURE Date: April 2018 Publisher: Aarhus 2017 Foundation Publication Manager and Editor: Rina Valeur Simonsen Monitoring and Research team: Anne Juhl Nielsen, Nana Renee Andersen, Brian Duborg Ebbesen, Maria Hyllested Poulsen Design: Hele Vejen Print: We Produce ISBN: 978-87-999627-7-8 Welcome Future Short-term impact of European Capital of Culture Aarhus 2017 Welcome Future / Intro 2 Aarhus 2017 Contents 4 Selected outcomes 6 Forewords 6 Mette Bock, Minister for Culture 7 Tibor Navracsics, European Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sport 8 ▪Anders Kühnau, Chair of the Regional Council, Central Denmark Region 9 ▪Jacob Bundsgaard, Mayor, Aarhus and Chair, Aarhus 2017 Foundation 10 ▪Rebecca Matthews, Chief Executive Officer, Aarhus 2017 Foundation 12 Six Strategic Goals and Key Performance Indicators 18 Executive Summary 20 Aarhus in Context 22 Methodology 24 Cultural Impact A stronger and more connected cultural sector 28 ▪A year like no other 36 ▪All art forms and more 44 ▪Something for everyone 48 Selected reviews 53 Local anchoring 56 ▪Grassroots engagement 58 ▪Inviting the world 68 Scaling up the cultural sector 74 Selected awards and nominations Welcome Future / Intro 3 Aarhus 2017 76 Social Impact Active and engaged citizens 80 Engagement through volunteering 90 Cultural community engagement 96 More culture for more people: making art accessible 102 Economic Impact Growth through investment 104 Economic outcome 106 Record growth in visitors 112 Tourist influx by boat and plane 116 Travelling business 118 New -

International Bachelor's Degree Programmes

Meet the world en.via.dk Denmark VIA University College International Bachelor’s Degree Programmes International Bachelor’s Degree Programmes VIA University College 5 CONTENT Content 07 Welcome 40 VIA Engineering 08 VIA University College 44 Civil Engineering 10 About Denmark 45 Global Business Engineering 11 Our Campus Cities 46 ICT Engineering 47 Materials Science & Product Design 12 VIA Built Environment 48 Mechanical Engineering 16 Architectural Technology & Construction 49 Supply Engineering DENMARK Management 50 VIA Summer School 18 VIA Business 22 Marketing Management 52 Campus Life 23 International Sales & Marketing Management 52 Aarhus 25 Value Chain Management 53 Herning 53 Horsens 26 VIA Design 30 Degree Programmes 54 Accommodation 31 Fashion Design 32 Pattern Design 56 Admission Requirements 33 Purchasing Management 34 Branding & Marketing Management 58 FAQ 36 Retail Design 37 Retail Management 60 Contact 38 Communication & Media Strategy 39 Entrepreneurship International Bachelor’s Degree Programmes VIA University College 7 DENMARK WELCOME Aalborg WELCOME TO VIA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE In Denmark, We offer you the We offer a range of acknow- Feel free to contact our everything is close by! opportunity to ledged international bachelor’s friendly, international staff for From our campuses, become part of a degree programmes in engi- further information. We also you can reach beaches, great university neering, design, construction welcome you to visit us and Viborg spectacular scenery and college community and business. learn more. big city life in no time. – a community that will provide you with You will learn from dedicated Yours sincerely, many possibilities to professors, work on projects Herning with Danish and internatio- Konstantin Lassithiotakis Aarhus explore your interests, nal companies, exchange Executive Director challenge and develop your professional ideas with students from VIA School of Business, knowledge and skills around the world, and Technology & Creative and help you reach your probably develop lasting Industries friendships. -

Braa-A-Nordic-Tech-Hub-2019.Pdf

Aarhus University is well known, and we have very good experience of recruiting graduates as software developers. They are Denmark has the Most flexible highly educated and skilled. And they do well – even if they go to world’s healthiest and liberal hiring/firing the United States, for example. They have no problem keeping work-life balance No. 1 – with above-average time spent practices up when they arrive in Silicon Valley. in the world for on leisure & personal care in the world worker motivation IMD OECD Better Life Index World Economic Forum Steffen Grarup, Director of Engineering, Uber ALL ABOUT MEET THE COMPANIES BUSINESS REGION Get to know some of the successful IT, tech and AARHUS communication companies that call this place home. A brief introduction to the region and its BUSINESS strengths. REGION AARHUS PAGES 6-11 PAGES 12-15 – A TECH RECRUITMENT RESEARCH EVENTS Go headhunting among one of Be inspired, meet like-minded Business Region Aarhus is a collaboration between & EDUCATION HUB IN the world’s best-educated and people and let your creativity 12 municipalities in East Jutland, Denmark. The region Our citizens have a generally most motivated workforces. run wild. is home to one million people and Denmark’s biggest higher level of education than in growth centre outside Copenhagen. GROWTH the rest of Denmark – and the scientific research is world-class. PAGE 16 PAGE 22 PAGE 24 THE GOOD LIFE The tech hub of Business Region Aarhus is a centre of increasing interna- INNOVATION Denmark ranks among the top countries tional attention. A dynamic community of cutting-edge entrepreneurs, R&D in the world for quality of life and work-life specialists and leading IT companies are driving unprecedented growth ENVIRONMENTS balance. -

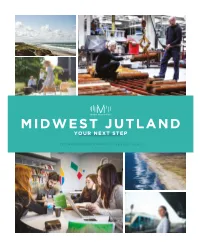

Midwest Jutland Your Next Step

MIDWEST JUTLAND YOUR NEXT STEP #THINKDENMARK #THINKMIDWESTJUTLAND 02 • MIDWEST JUTLAND - YOUR NEXT STEP AALBORG YOUR FUTURE - THINK KARUP MIDWEST JUTLAND MIDWEST JUTLAND AARHUS Midwest Jutland holds all the elements you and your family needs for a fulfilling and comfortable life. Midwest Jutland comprises 7 municipalities: Ikast-Brande, BILLUND COPENHAGEN Herning, Ringkøbing-Skjern, Holstebro, Lemvig, Struer & Skive. We have excellent infrastructure with more than 10.000 km of road in total, 101 km motorway and 36 DISTANCES FROM expressways. MIDWEST JUTLAND We have a lot of interesting and highly specialized companies producing a wide BY CAR range of products and services. With more than 45.000 companies, the area is a very Copenhagen 3h 30min Hamburg 4 hours attractive and diverse career destination. BY PLANE At the same time we have lots of space in our varied nature, good infrastructure and Copenhagen 50 min a safe and well-developed environment for a high quality life for you and your family. Amsterdam 1h 5min London 1h 35min We have everything from primary school to university. We also have an international primary school and an international baccalaureate school. HAMBURG 333.130 5.756.000 44.000 INHABITANTS IN SQUARE METERS OF COMPANIES RANGING MIDWEST JUTLAND FOREST, NATURE, FROM 1 TO 2.000 - AND COUNTING WATER AND CITIES EMPLOYEES 04 • MIDWEST JUTLAND - YOUR NEXT STEP MIDWEST JUTLAND - YOUR NEXT STEP • 05 BUSINESS & JOBS ADVANCED MANUFACTURING FOOD & AGRICULTURE The production companies in the area are the The area has a strong food cluster and is known Midwest Jutland can offer jobs within many competitive industries that are in primary driver for the growth and high employ- as a leading food manufacturing area, where constant development and incorporate cutting edge technology and innovation. -

A. Ministeriet for Forskning, Innovation Og Videregående Uddannelser

Aktstykke nr. 108 Folketinget 2011-12 Afgjort den 13. juni 2012 108 Ministeriet for Forskning, Innovation og Videregående Uddannelser. København, den 29. maj 2012. a. Ministeriet for Forskning, Innovation og Videregående Uddannelser anmoder om Finansudvalgets tilslutning til, at Professionshøjskolen VIA University College (herefter UC VIA) køber et nybyggeri på ca. 41.000 m2 på Ceres-grunden i Århus C for en samlet anlægsinvestering på 630 mio. kr. Da byggeriets opførelsessum overstiger 100 mio. kr., skal byggeprojektet forelægges Finansudval- get, jf. budgetvejledningens 2.11.5.4, 2.11.5.6 samt de særlige bevillingsbestemmelser under § 19.33.06. Institutionstilskud til professionshøjskoler, ingeniørhøjskoler og erhvervsakademier. Forslaget medfører ikke merudgifter for staten. b. Baggrund Den 1. januar 2008 blev UC VIA etableret som en sammenlægning af 5 Centre for Videregående Uddannelse, som alle var beliggende i Region Midtjylland. UC VIA har i perioden herefter arbejdet på at samle skolens uddannelsesaktivitet i færre og større uddannelsessteder for herigennem at kunne understøtte og fremtidssikre det faglige lærings- og vi- densmiljø. Senest er dette kommet til udtryk med etableringen af Campus N i Skejby tæt ved Skejby Sygehus, hvor sygeplejerskeuddannelsen, bioanalytikeruddannelsen, ergoterapeutuddannelsen, fysioterapeu- tuddannelsen, uddannelsen i ernæring og sundhed samt efter- og videreuddannelsesafdelingen er ble- vet samlet (jf. Akt 81 dateret den 13. januar 2009). På tilsvarende vis ønsker UC VIA med købet af byggeriet på Ceres-grunden at samle socialrådgi- veruddannelsen, administrationsbacheloruddannelsen, beklædningshåndværkeruddannelsen (er- hvervsuddannelse), design og business-uddannelsen, global business engineering-uddannelsen, value chain management-uddannelsen, læreruddannelsen, pædagoguddannelsen (som er placeret på to adresser: Skejbyvej 29 i Risskov og Peter Sabroesgade 12 og 14), center for undervisningsmidler samt ledelsen og det tilhørende sekretariat fra Pædagogisk-Socialfaglig Højskole.