Boosting India's Military Presence in Outer Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Militarisation of Space 14 June 2021

By, Claire Mills The militarisation of space 14 June 2021 Summary 1 Space as a new military frontier 2 Where are military assets in space? 3 What are counterspace capabilities? 4 The regulation of space 5 Who is leading the way on counterspace capabilities? 6 The UK’s focus on space commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number 9261 The militarisation of space Contributing Authors Patrick Butchard, International Law, International Affairs and Defence Section Image Credits Earth from Space / image cropped. Photo by ActionVance on Unsplash – no copyright required. Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected]. Please note that authors are not always able to engage in discussions with members of the public who express opinions about the content of our research, although we will carefully consider and correct any factual errors. -

Weaponisation of Space

MANEKSHAW PAPER No. 45, 2014 Weaponisation of Space Puneet Bhalla D W LAN ARFA OR RE F S E T R U T D N IE E S C CLAWS VI CT N OR ISIO Y THROUGH V KNOWLEDGE WORLD Centre for Land Warfare Studies KW Publishers Pvt Ltd New Delhi New Delhi Editorial Team Editor-in-Chief : Maj Gen Dhruv C Katoch SM, VSM (Retd) Managing Editor : Ms Geetika Kasturi D W LAN ARFA OR RE F S E T R U T D N IE E S C CLAWS VI CT N OR ISIO Y THROUGH V Centre for Land Warfare Studies RPSO Complex, Parade Road, Delhi Cantt, New Delhi 110010 Phone: +91.11.25691308 Fax: +91.11.25692347 email: [email protected] website: www.claws.in The Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi, is an autonomous think tank dealing with national security and conceptual aspects of land warfare, including conventional and sub-conventional conflicts and terrorism. CLAWS conducts research that is futuristic in outlook and policy-oriented in approach. © 2014, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi Disclaimer: The contents of this paper are based on the analysis of materials accessed from open sources and are the personal views of the author. The contents, therefore, may not be quoted or cited as representing the views or policy of the Government of India, or Integrated Headquarters of MoD (Army), or the Centre for Land Warfare Studies. KNOWLEDGE WORLD www.kwpub.com Published in India by Kalpana Shukla KW Publishers Pvt Ltd 4676/21, First Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110002 Phone: +91 11 23263498 / 43528107 email: [email protected] l www.kwpub.com Contents Abbreviations v 1. -

Outer Space in Russia's Security Strategy

Outer Space in Russia’s Security Strategy Nicole J. Jackson Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 64/2018 | August 2018 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 64/2018 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Jackson, Nicole J., Outer Space in Russia’s Security Strategy, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 64/2018, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, August 2018. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright remains with the author. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Copyright for this issue: Nicole J. Jackson, nicole_jackson(at)sfu.ca. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Outer Space in Russia’s Security Strategy 3 Outer Space in Russia’s Security Strategy Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

ORF Issue Brief 59 Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan

ORF ISSUE BRIEF OCTOBER 2013 ISSUE BRIEF # 59 Synergies in Space: The Case for an Indian Aerospace Command Dr. Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan Introduction he Indian Armed Forces have been mulling over the establishment of an aerospace command for close to a decade now. Over those years, international circumstances and Tgeopolitics relating to outer space have changed, making it imperative for India to make decisions now. Though outer space is part of the global commons, it is increasingly getting appropriated and fenced as powerful States are seen seeking to monopolise space. The growing advanced military space capabilities of some nations, which include the development of their anti-satellite missile capabilities, are also a worrying trend. With much of outer space having been utilised by a small number of great powers and the increasing presence of non-state players in the recent years, even a nominal increase in terms of space activity by some developing countries is leading to issues related to overcrowding and access. In order to protect its interests, India must institutionalise its own strengths in the form of an Aerospace Command. While all the three services are becoming increasingly reliant on outer space assets, the Indian Air Force (IAF) has taken the lead, at least going by open sources. Back in 2003, Indian Air Force Chief Air Marshal S Krishnaswamy had already articulated the need for an aerospace command: “Any country on the fringe of space technology like India has to work towards such a command as advanced countries are already moving towards laser weapon platforms in space and killer satellites.” Some years after that, in 2006, the IAF established a Directorate of Aerospace in Thiruvananthapuram in South India, which can be referred to as the initial avatar of the Indian Observer Research Foundation is a public policy think-tank that aims to influence formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. -

T He Indian Army Is Well Equipped with Modern

Annual Report 2007-08 Ministry of Defence Government of India CONTENTS 1 The Security Environment 1 2 Organisation and Functions of The Ministry of Defence 7 3 Indian Army 15 4 Indian Navy 27 5 Indian Air Force 37 6 Coast Guard 45 7 Defence Production 51 8 Defence Research and Development 75 9 Inter-Service Organisations 101 10 Recruitment and Training 115 11 Resettlement and Welfare of Ex-Servicemen 139 12 Cooperation Between the Armed Forces and Civil Authorities 153 13 National Cadet Corps 159 14 Defence Cooperaton with Foreign Countries 171 15 Ceremonial and Other Activities 181 16 Activities of Vigilance Units 193 17. Empowerment and Welfare of Women 199 Appendices I Matters Dealt with by the Departments of the Ministry of Defence 205 II Ministers, Chiefs of Staff and Secretaries who were in position from April 1, 2007 onwards 209 III Summary of latest Comptroller & Auditor General (C&AG) Report on the working of Ministry of Defence 210 1 THE SECURITY ENVIRONMENT Troops deployed along the Line of Control 1 s the world continues to shrink and get more and more A interdependent due to globalisation and advent of modern day technologies, peace and development remain the central agenda for India.i 1.1 India’s security environment the deteriorating situation in Pakistan and continued to be infl uenced by developments the continued unrest in Afghanistan and in our immediate neighbourhood where Sri Lanka. Stability and peace in West Asia rising instability remains a matter of deep and the Gulf, which host several million concern. Global attention is shifting to the sub-continent for a variety of reasons, people of Indian origin and which is the ranging from fast track economic growth, primary source of India’s energy supplies, growing population and markets, the is of continuing importance to India. -

Annual Report 2017 - 2018 Annual Report 2017 - 2018 Citizens’ Charter of Department of Space

GSAT-17 Satellites Images icro M sat ries Satellit Se e -2 at s to r a C 0 SAT-1 4 G 9 -C V L S P III-D1 -Mk LV GS INS -1 C Asia Satell uth ite o (G S S A T - 09 9 LV-F ) GS ries Sat Se ellit t-2 e sa to 8 r -C3 a LV C PS Annual Report 2017 - 2018 Annual Report 2017 - 2018 Citizens’ Charter of Department Of Space Department Of Space (DOS) has the primary responsibility of promoting the development of space science, technology and applications towards achieving self-reliance and facilitating in all round development of the nation. With this basic objective, DOS has evolved the following programmes: • Indian National Satellite (INSAT) programme for telecommunication, television broadcasting, meteorology, developmental education, societal applications such as telemedicine, tele-education, tele-advisories and similar such services • Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellite programme for the management of natural resources and various developmental projects across the country using space based imagery • Indigenous capability for the design and development of satellite and associated technologies for communications, navigation, remote sensing and space sciences • Design and development of launch vehicles for access to space and orbiting INSAT / GSAT, IRS and IRNSS satellites and space science missions • Research and development in space sciences and technologies as well as application programmes for national development The Department Of Space is committed to: • Carrying out research and development in satellite and launch vehicle technology with a goal to achieve total self reliance • Provide national space infrastructure for telecommunications and broadcasting needs of the country • Provide satellite services required for weather forecasting, monitoring, etc. -

COMMITTEE on the PEACEFUL USES of OUTER SPACE Chaired by Alan Lai

COMMITTEE ON THE PEACEFUL USES OF OUTER SPACE Chaired by Alan Lai Session XXII Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space Topic A: Regulating the Militarization of Outer Space Topic B: R egulating Commercial Activity in Outer Space Committee Overview ad hoc committee, with 18 inaugural members, including the two major parties The United Nations Committee on involved in the space race: the United States the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space of America and the Soviet Union. In 1959, (COPUOS) was set up by the United the U.N. General Assembly officially Nations General Assembly in 1959. established COPUOS as a permanent body, Founded because of the implications that which had 24 members at that time.1 the successful launch of Sputnik had for the COPUOS now has 87 members, and world, COPUOS’s mission is to review maintains its goal as “a focal point for international cooperation in peaceful uses international cooperation in the peaceful of outer space, to study spacerelated exploration and use of outer space, activities that could be undertaken by the maintaining close contacts with United Nations, to encourage space governmental and nongovernmental research programmes, and to study legal organizations concerned with outer space problems arising from the exploration of activities, providing for exchange of 1 outer space. information relating to outer space The United Nations realized early on activities and assisting in the study of that space would be the next frontier for measures for the promotion of international exploration, and so it has been involved in cooperation in those activities.”2 In addition space activities since the beginning of the to being one of the largest committees in space age. -

The Great Game in Space China’S Evolving ASAT Weapons Programs and Their Implications for Future U.S

The Great Game in Space China’s Evolving ASAT Weapons Programs and Their Implications for Future U.S. Strategy Ian Easton The Project 2049 Institute seeks If there is a great power war in this century, it will not begin to guide decision makers toward with the sound of explosions on the ground and in the sky, but a more secure Asia by the rather with the bursting of kinetic energy and the flashing of century’s mid-point. The laser light in the silence of outer space. China is engaged in an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons drive that has profound organization fills a gap in the implications for future U.S. military strategy in the Pacific. This public policy realm through Chinese ASAT build-up, notable for its assertive testing regime forward-looking, region-specific and unexpectedly rapid development as well as its broad scale, research on alternative security has already triggered a cascade of events in terms of U.S. and policy solutions. Its strategic recalibration and weapons acquisition plans. The interdisciplinary approach draws notion that the U.S. could be caught off-guard in a “space on rigorous analysis of Pearl Harbor” and quickly reduced from an information-age socioeconomic, governance, military juggernaut into a disadvantaged industrial-age power in any conflict with China is being taken very seriously military, environmental, by U.S. war planners. As a result, while China’s already technological and political impressive ASAT program continues to mature and expand, trends, and input from key the U.S. is evolving its own counter-ASAT deterrent as well as players in the region, with an eye its next generation space technology to meet the challenge, toward educating the public and and this is leading to a “great game” style competition in informing policy debate. -

Europe, Space and Defence Report Presentation at the Institute for Foreign Affairs and Trade (IFAT)

Europe, Space and Defence Report presentation at the Institute for Foreign Affairs and Trade (IFAT) Mathieu Bataille 19 November 2020 What is ESPI? ESPI is the European think-tank for space. The institute provides decision-makers with an informed view on mid to long-term issues relevant to Europe’s space activities. Research & Conferences & Space sector Analysis Workshops watch Policy & Economy & Security & International & Strategy Business Defence Legal Download our reports, check our events and subscribe to our newsletter online www.espi.or.at Introduction – Definitions Space for Defence Defence of Space • 4 main applications: • Protection of space systems in: ➢ Intelligence, Surveillance and ➢ Space segment Reconnaissance (ISR) ➢ Ground segment ➢ Satellite communications (SATCOM) ➢ Link segment ➢ Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) ➢ Space surveillance Introduction – Why this report? • Evolution of the space environment due to two elements: 1) A capability-related element ➢ Growing development of ASAT systems of all kinds Denial, Physical Degradation, disruption, Interception destruction interruption interference Kinetic weapons Yes Yes No No (e.g. ASAT missile) Directed-energy weapons No Yes Yes No (e.g. blinding lasers) Electronic warfare No No Yes No (e.g. jamming, spoofing) Cyber attacks Possible Possible Possible Possible (e.g. system compromise) ➢ Questions raised by dual-use systems (e.g. RPO technologies) Introduction – Why this report? 2) A political element ➢ Growing tensions between states + evolution of the balance -

INDIA JANUARY 2018 – June 2020

SPACE RESEARCH IN INDIA JANUARY 2018 – June 2020 Presented to 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, Sydney, Australia | Jan 28–Feb 4, 2021 SPACE RESEARCH IN INDIA January 2018 – June 2020 A Report of the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) Indian National Science Academy (INSA) Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) For the 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly 28 January – 4 Febuary 2021 Sydney, Australia INDIAN SPACE RESEARCH ORGANISATION BENGALURU 2 Compiled and Edited by Mohammad Hasan Space Science Program Office ISRO HQ, Bengalure Enquiries to: Space Science Programme Office ISRO Headquarters Antariksh Bhavan, New BEL Road Bengaluru 560 231. Karnataka, India E-mail: [email protected] Cover Page Images: Upper: Colour composite picture of face-on spiral galaxy M 74 - from UVIT onboard AstroSat. Here blue colour represent image in far ultraviolet and green colour represent image in near ultraviolet.The spiral arms show the young stars that are copious emitters of ultraviolet light. Lower: Sarabhai crater as imaged by Terrain Mapping Camera-2 (TMC-2)onboard Chandrayaan-2 Orbiter.TMC-2 provides images (0.4μm to 0.85μm) at 5m spatial resolution 3 INDEX 4 FOREWORD PREFACE With great pleasure I introduce the report on Space Research in India, prepared for the 43rd COSPAR Scientific Assembly, 28 January – 4 February 2021, Sydney, Australia, by the Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR), Indian National Science Academy (INSA), and Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO). The report gives an overview of the important accomplishments, achievements and research activities conducted in India in several areas of near- Earth space, Sun, Planetary science, and Astrophysics for the duration of two and half years (Jan 2018 – June 2020). -

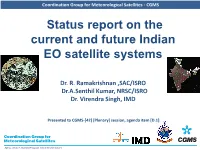

Status Report on the Current and Future Indian EO Satellite Systems

Coordination Group for Meteorological Satellites - CGMS Status report on the current and future Indian EO satellite systems Dr. R. Ramakrishnan ,SAC/ISRO Dr.A.Senthil Kumar, NRSC/ISRO Dr. Virendra Singh, IMD Presented to CGMS-[42] [Plenary] session, agenda item [D.1] Agency, version?, Date 2014? [update filed in the slide master] Indian Earth Observation Satellites • One of the largest constellations 2009 2012 • Provides remote RISAT-2 RISAT-1 2007/ 2008/ 2010 X-SAR C-SAR sensing data in a CARTOSAT-2/2A/2B PAN variety of spatial, 2011 spectral and temporal RESOURCESAT-2 LISS 3; LISS 4; AWiFS resolutions 2005 • Both Optical and 2003 CARTOSAT-1 Microwave RESOURCESAT-1 Stereo PAN, F/A LISS 3; LISS 4; AWiFS 2008 2001 IMS-1 TES Step 2009 MX-T; HySI & Stare PAN OCEANSAT-2 OCM , SCAT 2013 ROSA INSAT-3D IMAGER, SOUNDER 2003 2013 INSAT- 3A SARAL VHRR, CCD ALTIKA, ARGOS 2011 2002 Megha-Tropiques KALPANA-1 MADRAS, SAPHIR, SCaRaB VHRR Oceansat-2 (2009) A global mission, providing continuity of ocean color data and wind vector in addition characterization of lower atmosphere and ionosphere from ROSA payload. Global data acquisition of Ocean colour • High Resolution Data - NRSC and INCOIS • 1km resolution global products through NRSC Website • Global Chlorophyll, Aerosol Optical Depth through NRSC Website • Regional/Global NDVI, VF, Albedo products Scatterometer Wind Products • Reception Station at Svalbard • Real time transfer and processing • Uploading to Web within 3 hrs through EUMETCAST • 1.72 Lakhs data are downloaded from NRSC Website Data Dissemination Mechanism • Established Ground station at INCOIS • Ground station at Bharti, Antarctica is commissioned. -

Militarization and Weaponization of Outer Space in International Law*

航空宇宙政策․法學會誌 第 33 卷 第 1 號 논문접수일 2018. 05. 30 2018년 6월 30일 발행, pp. 261~284 논문심사일 2018. 06. 10 http://dx.doi.org/10.31691/KASL 33.1.9. 게재확정일 2018. 06. 25 Militarization and Weaponization of Outer Space in International Law* Kim, Han-Taek** 44) Contents Ⅰ. Introduction Ⅱ. Militarization of Outer Space Ⅲ. Weaponization of Outer Space Ⅳ. Conclusion * This study was supported by 2017 Research Grant from Kangwon National University. ** Professor of International Law, Kangwon National University, School of Law, Korea, E-Mail : [email protected] 262 航空宇宙政策․法學會誌 第 33 卷 第 1 號 Ⅰ. Introduction In the early 20th century the modern space age began with the development of rocket and missile science. Germany was a major player in rocket science at the time of the Second World War. With tremendous government support, it led to the development of the V-2 rocket,1) which was recognized as the first space rocket. After World War II, a small group of German rocket scientists from the V-2 rocket project were brought to the United States to continue their research, which became the basis of the first space rocket program. The Soviet Union also had access to V-2 technology, launching the world's first satellite, Sputnik I, in 1957. The launch of Sputnik I marked the beginning of space exploration and with it the start of the debate surrounding the militarization of outer space.2) It also invoked a 'space-race' between the US and the Soviet Union after the realization that a surprise attack from outer space was indeed possible.