African Wave Specificity and Cosmopolitanism in African Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comics and War

Representations of war Comics and War Mathieu JESTIN Bettina SEVERIN-BARBOUTIE ABSTRACT Recounting war has always played a role in European comics, whether as an instrument of propaganda, heroisation or denunciation. But it is only in recent decades that the number of stories about war has proliferated, that the range of subjects, spaces treated and perspectives has increased, and that the circulation of stories across Europe has become more pronounced. For this reason, comic books feed into a shared collection of popular narratives of war just as they fuel anti-war representations. "“Everyone Kaputt. The First World War in Comic Books.” Source: with the kind permission of Barbara Zimmermann. " In Europe, there is growing public interest in what is known in France as the ‘ninth art’. The publishing of comic books and graphic novels is steadily increasing, including a growing number which deal with historical subjects; comic book festivals are increasing in number and the audience is becoming larger and more diverse. Contrary to received ideas, the comic is no longer merely ‘an entertainment product’; it is part of culture in its own right, and a valid field of academic research. These phenomena suggest that the comic, even if it is yet to gain full recognition in all European societies, at least meets with less reticence than it faced in the second half of the twentieth century. It has evolved from an object arousing suspicion, even rejection, into a medium which has gained wide recognition in contemporary European societies. War illustrated: themes and messages As in other media in European popular culture, war has always been a favourite subject in comics, whether at the heart of the narrative or in the background. -

Republique Democratique Du Congo

ETUDE DE L’IMPACT DES ARTS, DE LA CULTURE ET DES INDUSTRIES CREATIVES SUR L’ ECONOMIE EN AFRIQUE REPUBLIQUE DEMOCRATIQUE DU CONGO Projet développé et exécuté par Agoralumiere en collaboration avec CAJ(Afrique du Sud) commandé par ARTerial Network et financé par la Foundation DOEN , la Foundation Stomme et la République Fédérale du Nigeria Ministry of Commerce and Industry Federal Republic of Nigeria Democratic Republic of Congo Africa Union www.creative-africa.org Agoralumiere 2009 Remerciements Cette étude pilote a été commandée par ARTERIAL NETWORK et conjointement financée par STICHTING DOEN, la Fondation STROMME et le Gouvernement de la République Fédérale du Nigeria. Agoralumiere a été soutenue par l’Union Africaine pour la conduite de ce travail de recherche pilote dans le cadre de la mise en œuvre du Plan d’Action des Industries Culturelles et Créatives reformulé par Agoralumiere à la demande de la Commission et qui fut adopté en octobre 2008 par les Ministres de la Culture de l’Union Africaine. Agoralumiere a aussi été soutenue par le gouvernement de la République Démocratique du Congo, et particulièrement par le Cabinet du Premier Ministre qui entend utiliser ce travail de base pour élaborer une suite plus approfondie au niveau national, avec des chercheurs nationaux déjà formés dans le secteur. Agoralumiere a enfin été soutenue par le Dr Bamanga Tukur, Président du African Business Roundtable et du NEPAD Business Group. Agoralumiere tient à remercier tous ceux dont la participation directe et la contribution indirecte ont appuyé -

Belgique Francophone, Terre De B.D

Belgique francophone, terre de B.D. François Pierlot Frantseseko lektorea / Lector de francés Laburpena Komikien historia Suitzan hasi zen 1827an, Rodolphe Töpffer-ek “litera- tura iruditan” deiturikoa sortu zuenean. Printzipioa sinplea da: istorio bat kontatzen du marrazki bidez, eta istorioa azaltzeko testuak eransten ditu. Hogei urte geroago, Wilhelm Bush alemaniarrak Max und Moritz sortu zuen, marrazkietan dinamismo handia zuen umorezko komikia. Gero, batez ere egunkarietan agertzen hasi ziren komikiak. Eguneroko prentsak ere gero eta arrakasta handiagoa zuenez, komikiak Europa osora za- baldu ziren. Egunkarientzat oso garrantzitsua zen komiki onak izatea, irakur- le asko erakartzen zituztelako. Erresuma Batuan ere arrakasta izan zuten ko- mikiek. AEBtik, bestalde, koloretako argitalpenak iristen hasi ziren, testuen ordez bunbuiloak zituztenak. Belgikan, 1929an hasi ziren komikiak argitaratzen, Le petit vingtième haurrentzako egunkarian. Apaiz oso kontserbadore bat zen erredakzioburua, eta umeei komunisten alderako gorrotoa barneratzeko pertsonaia asmatzeko eskatu zion Hergé marrazkilari gazteari. Horrela sortu zen Tintin. Lehenengo aleak Tintin sobieten herrialdean zuen izenburua. Hergék bere pertsonaiaren «gobernua» hartu baino lehen, ideologiaz beteriko beste bi abentura ere izan ziren (Tintin Kongon eta Tintin Amerikan). Tintinekin hasitako goraldiaren ondoren, beste marrazki-aldizkari bel- gikar batzuk sortu ziren; besteak beste, Bravo! agerkaria. Komiki belgikarrak 1940ko hamarkadatik aurrera nagusitu ziren mundu frantsestunean, bi agerkari zirela bitarte: Le Journal Tintin eta Le Journal de Spirou, hurrenez hurren, Hergé eta Franquin marrazkilari zirela. Bi astekariek talentu gazteak hartu zituzten, aukera bat emateko. Komikien ibilbidea finka- tu zuten, klasizismo mota bat ezarrita. Journal de Spirou izenekoa 1938an sortu zuen Dupuis argitaletxeak, eta umorea landu zuen. Pertsonaiek oso jatorrak dirudite, grafismo biribilari esker (horregatik aipatzen da “sudur lodiaren” estiloa). -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

Bruxelles, Capitale De La Bande Dessinée Dossier Thématique 1

bruxelles, capitale de la bande dessinée dossier thématique 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINÉE a. Naissance de la BD à Bruxelles b. Du héros de BD à la vedette de cinéma 2. LA BANDE DESSINÉE, PATRIMOINE DE BRUXELLES a. Publications BD b. Les fresques BD c. Les bâtiments et statues incontournables d. Les musées, expositions et galeries 3. LES ACTIVITÉS ET ÉVÈNEMENTS BD RÉCURRENTS a. Fête de la BD b. Les différents rendez-vous BD à Bruxelles c. Visites guidées 4. SHOPPING BD a. Adresses b. Librairies 5. RESTAURANTS BD 6. HÔTELS BD 7. CONTACTS UTILES www.visitbrussels.be/comics BRUXELLES EST LA CAPITALE DE LA BANDE DESSINEE ! DANS CHAQUE QUARTIER, AU DÉTOUR DES RUES ET RUELLES BRUXELLOISES, LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST PAR- TOUT. ELLE EST UNE FIERTÉ NATIONALE ET CELA SE RES- SENT PARTICULIÈREMENT DANS NOTRE CAPITALE. EN EFFET, LES AUTEURS BRUXELLOIS AYANT CONTRIBUÉ À L’ESSOR DU 9ÈME ART SONT NOMBREUX. VOUS L’APPRENDREZ EN VISITANT UN CENTRE ENTIÈREMENT DÉDIÉ À LA BANDE DESSINÉE, EN VOUS BALADANT AU CŒUR D’UN « VILLAGE BD » OU ENCORE EN RENCON- TRANT DES FIGURINES MONUMENTALES ISSUES DE PLUSIEURS ALBUMS D’AUTEURS BELGES… LA BANDE DESSINÉE EST UN ART À PART ENTIÈRE DONT LES BRUX- ELLOIS SONT PARTICULIÈREMENT FRIANDS. www.visitbrussels.be/comics 1. BRUXELLES ET LA BANDE DESSINEE A. NAISSANCE DE LA BD À BRUXELLES Raconter des histoires à travers une succession d’images a toujours existé aux quatre coins du monde. Cependant, les spéciali- stes s’accordent à dire que la Belgique est incontournable dans le milieu de ce que l’on appelle aujourd’hui la bande dessinée. -

Hergé and Tintin

Hergé and Tintin PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Fri, 20 Jan 2012 15:32:26 UTC Contents Articles Hergé 1 Hergé 1 The Adventures of Tintin 11 The Adventures of Tintin 11 Tintin in the Land of the Soviets 30 Tintin in the Congo 37 Tintin in America 44 Cigars of the Pharaoh 47 The Blue Lotus 53 The Broken Ear 58 The Black Island 63 King Ottokar's Sceptre 68 The Crab with the Golden Claws 73 The Shooting Star 76 The Secret of the Unicorn 80 Red Rackham's Treasure 85 The Seven Crystal Balls 90 Prisoners of the Sun 94 Land of Black Gold 97 Destination Moon 102 Explorers on the Moon 105 The Calculus Affair 110 The Red Sea Sharks 114 Tintin in Tibet 118 The Castafiore Emerald 124 Flight 714 126 Tintin and the Picaros 129 Tintin and Alph-Art 132 Publications of Tintin 137 Le Petit Vingtième 137 Le Soir 140 Tintin magazine 141 Casterman 146 Methuen Publishing 147 Tintin characters 150 List of characters 150 Captain Haddock 170 Professor Calculus 173 Thomson and Thompson 177 Rastapopoulos 180 Bianca Castafiore 182 Chang Chong-Chen 184 Nestor 187 Locations in Tintin 188 Settings in The Adventures of Tintin 188 Borduria 192 Bordurian 194 Marlinspike Hall 196 San Theodoros 198 Syldavia 202 Syldavian 207 Tintin in other media 212 Tintin books, films, and media 212 Tintin on postage stamps 216 Tintin coins 217 Books featuring Tintin 218 Tintin's Travel Diaries 218 Tintin television series 219 Hergé's Adventures of Tintin 219 The Adventures of Tintin 222 Tintin films -

Ligne-Claire.Pdf

neuviemeart2.0 > dictionnaire esthétique et thématique de la bande dessinée > ligne claire ligne claire par Thierry Groensteen [Novembre 2013] Baptisée en 1977 par Joost Swarte à la faveur du catalogue d’une exposition présentée à Rotterdam, la klare lijn − en français : ligne claire – désigne, au sens le plus restrictif, le style d’Hergé, et, dans son acception la plus large, une mouvance aux contours assez flous regroupant de nombreux artistes de bande dessinée et illustrateurs animés par un même souci d’épure, de lisibilité, une même confiance dans le cerne, le trait net et la couleur en aplat. La bande dessinée a toujours privilégié le dessin au trait, qui a l’avantage d’être rapide d’exécution et de se prêter parfaitement aux exigences de la reproduction, quel que soit le support. Dans le Livre Troisième de son traité Réflexions et menus propos d’un peintre genevois, Rodolphe Töpffer exprimait déjà « la prééminence du trait sur les deux autres moyens, le relief et la couleur, quant à ce qui caractérise l’imitation ». À lui seul, en se concentrant sur le contour, « il représente l’objet d’une façon suffisante, sinon complète ». Des trois moyens d’imitation, le trait est celui « qui dit le plus rapidement les choses les plus claires à notre intelligence, et qui rappelle le plus spontanément les objets ». Cela vient − précisera Töpffer dans l’Essai de physiognomonie (1848) − « de ce qu’il ne donne de l’objet que ses caractères essentiels, en supprimant ceux qui sont accessoires » (matières, modelés, demi-tons, détails, contrastes dus à l’éclairage, etc.). -

Jornal Do Próximo Futuro

SECÇÃOFICHA TÉCNICA FUNDAÇÃO CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN FUNDAÇÃO CALOUSTE GULBENKIAN PRÓXIMO FUTURO / NEXT FUTURE PRÓXIMO FUTURO / NEXT FUTURE PÁGINA: 2 PÁGINA: 3 Nuno Cera Futureland, Cidade do Mexico, 2009 Cortesia do artista e da Galeria Cortesía del artista y de la Galería Courtesy of the artist and of the Gallery Pedro Cera, Lisboa → Próximo Futuro é um Programa Gulbenkian de Cultura Contemporânea dedicado em particular, mas não exclusivamente, à investigação e criação na Europa, na América Latina e Caraíbas e em África. O seu calendário de realização é do Verão de 2009 ao fim de 2011. MARÇO NEXT FUTURE Próximo Futuro es un Programa Gulbenkian de Cultura Contemporánea dedicado, particular MARZO aunque no exclusivamente, a la investigación y la creación en Europa, África, América Latina y el Caribe. Su calendario de realización transcurrirá entre el verano de 2009 y 2011. MARCH PRÓXIMO FUTURO Next Future is a Gulbenkian Programme of Contemporary Culture dedicated in particular, but not exclusively, to research and creation in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Baudouin Mouanda “Borders” is the theme of the exhibition of photography by Afri- Africa. It will be held from Summer 2009 to Cortesia do artista / Cortesía del artista / can and Afro-American artists, which will be opening on 13 May. FRONTERAS Isabel Mota the end of 2011. Courtesy of the artist It is not the first time that such a theme has been included in the programme of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, for several BORDERS seminars and workshops have already been held on this topic, together with the production of films and the organisation of “Fronteras” es el tema de la exposición de fotografía de artistas performances and shows. -

Západočeská Univerzita V Plzni Fakulta Pedagogická

Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta pedagogická Bakalářská práce VZESTUP AMERICKÉHO KOMIKSU DO POZICE SERIÓZNÍHO UMĚNÍ Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 University of West Bohemia Faculty of Education Undergraduate Thesis THE RISE OF THE AMERICAN COMIC INTO THE ROLE OF SERIOUS ART Jiří Linda Plzeň 2012 Tato stránka bude ve svázané práci Váš původní formulář Zadáni bak. práce (k vyzvednutí u sekretářky KAN) Prohlašuji, že jsem práci vypracoval/a samostatně s použitím uvedené literatury a zdrojů informací. V Plzni dne 19. června 2012 ……………………………. Jiří Linda ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank to my supervisor Brad Vice, Ph.D., for his help, opinions and suggestions. My thanks also belong to my loved ones for their support and patience. ABSTRACT Linda, Jiří. University of West Bohemia. May, 2012. The Rise of the American Comic into the Role of Serious Art. Supervisor: Brad Vice, Ph.D. The object of this undergraduate thesis is to map the development of sequential art, comics, in the form of respectable art form influencing contemporary other artistic areas. Modern comics were developed between the World Wars primarily in the United States of America and therefore became a typical part of American culture. The thesis is divided into three major parts. The first part called Sequential Art as a Medium discusses in brief the history of sequential art, which dates back to ancient world. The chapter continues with two sections analyzing the comic medium from the theoretical point of view. The second part inquires the origin of the comic book industry, its cultural environment, and consequently the birth of modern comic book. -

2019-09-12-Pk-Fbd-Final.Pdf

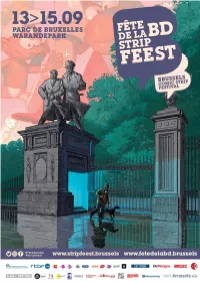

PRESS KIT Brussels, September 2019 The 2019 Brussels Comic Strip Festival Brussels is holding its 10th annual Comic Strip Festival from 13 to 15 September 2019 From their beginning at the turn of the previous century, Belgian comics have really become famous the world over. Many illustrators and writers from our country and its capital are well- known beyond our borders. That is reason enough to dedicate a weekend to this rich cultural heritage. Since its debut in 2010, the Brussels Comic Strip Festival has become the main event for comics fans. Young and old, novices and experts, all share a passion for the ninth art and come together each year to participate in the variety of activities on offer. More than 100,000 people and some 300 famous authors gather every year. For this 2019 edition, the essential events are definitely on the schedule: autograph sessions, the Balloon's Day Parade and many more. There's a whole range of activities to delight everyone. Besides the Parc de Bruxelles, le Brussels Comic Strip Festival takes over the prestigious setting of Brussels' Palais des Beaux-Arts, BOZAR. Two places that pair phenomenally well together for the Brussels Comic Strip Festival. Festival-goers will be able to stroll along as they please, enjoying countless activities and novelties on offer wherever they go. From hundreds of autograph signings to premiere cartoon screenings and multiple exhibitions and encounters with professionals, ninth art fans will have plenty to keep them entertained. Finally, the Brussels Comic Strip Festival will award comics prizes: The Atomium Prizes, during a gala evening when no less than €90,000 will be awarded for the best new works from the past year. -

Belgian Beer Experiences in Flanders & Brussels

Belgian Beer Experiences IN FLANDERS & BRUSSELS 1 2 INTRODUCTION The combination of a beer tradition stretching back over Interest for Belgian beer and that ‘beer experience’ is high- centuries and the passion displayed by today’s brewers in ly topical, with Tourism VISITFLANDERS regularly receiving their search for the perfect beer have made Belgium the questions and inquiries regarding beer and how it can be home of exceptional beers, unique in character and pro- best experienced. Not wanting to leave these unanswered, duced on the basis of an innovative knowledge of brew- we have compiled a regularly updated ‘trade’ brochure full ing. It therefore comes as no surprise that Belgian brew- of information for tour organisers. We plan to provide fur- ers regularly sweep the board at major international beer ther information in the form of more in-depth texts on competitions. certain subjects. 3 4 In this brochure you will find information on the following subjects: 6 A brief history of Belgian beer ............................. 6 Presentations of Belgian Beers............................. 8 What makes Belgian beers so unique? ................12 Beer and Flanders as a destination ....................14 List of breweries in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours for groups .......................18 8 12 List of beer museums in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours .......................................... 36 Pubs ..................................................................... 43 Restaurants .........................................................47 Guided tours ........................................................51 List of the main beer events in Flanders and Brussels ......................................... 58 Facts & Figures .................................................... 62 18 We hope that this brochure helps you in putting together your tours. Anything missing? Any comments? 36 43 Contact your Trade Manager, contact details on back cover. -

TEEN AGE -A Construção Da Narrativa Gráfica a Partir Da Autobiografia

TEEN AGE A Construção da Narrativa Gráfica a Partir da Autobiografia Ana Raquel Cunha Diogo Relatório de Projeto para Obtenção de grau de Mestre em Artes Plásticas, Especialização em Desenho Orientador Professor Doutor Mário Moura Porto, 2019 Agradecimentos | i Quero agradecer ao meu orientador, Professor Mário Moura, pela sua disponibilidade em orientar-me, e acompanhar-me ao longo deste processo de trabalho. Agradeço principalmente aos meus pais pelo apoio e esforço que sempre fizeram ao longo destes anos de estudo. A Bárbara e Maria, que sempre me acompanharam durante este caminho e sempre me incentivaram para continuar, às suas recomendações e conhecimentos partilhados. Ao Pedro, pela paciência e motivação, e por me ajudar a nunca desistir. Aos meus colegas e amigos de mestrado, pelos bons e maus momentos, entreajuda, partilha de ideias e opiniões. Resumo | ii O presente relatório de projeto tem como principal objetivo abordar a banda desenhada autobiográfica como um modo expressivo de contar histórias aos quadradinhos em que os autores se assumem nas suas histórias como personagens, da mesma forma que se expressam perante a sociedade. O nosso caso de estudo é a banda desenhada do movimento artístico norte-americano criado na década de 60 e chamado Comix-Underground. A autobiografia é uma forma inevitável de exprimir o pessoal de cada um, visível ao leitor. Falamos assim de um projeto autorrepresentativo e do papel da mulher na sociedade nomeadamente na prática de skate na qual é assumida com a dominação masculina e se torna visível a desigualdade entre estes experienciando assim pequenos episódios de discriminação, preconceitos e estereótipos presentes na modalidade.