Shaping Suburbia: a Comparison of State-Led and Market-Led Suburbs In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area 2013. 11. Presenter : Dr. Sang Keon Lee Co-author: Dr. Sang Min Lee(KOTI) General Information Seoul (Area=605㎢, 10mill. 23.5%) - Population of South Korea : 51.8 Million (‘13) Capital Region (Area=11,730㎢, 25mill. 49.4%)- Size of South Korea : 99,990.5 ㎢ - South Korean Capital : Seoul 2 Ⅰ. Major changes of recent decades in Korea Korea’s Pathways at a glance 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Economic Economic Heavy-Chem. Stabilization-Growth- Economic Crisis & Post-war recovery Development takeoff Industry drive Balancing-Deregulation Restructuring Development of Balanced Territorial Post-war Growth pole Regional growth Promotion Industrialization regional Development reconstruction development Limit on urban growth base development Post-war Construction of Highways & National strategic networks Environ. friendly Transport reconstruction industrial railways Urban subway / New technology 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Population 20,189 24,989 31,435 37,407 43,390 45,985 48,580 (1,000 pop.) GDP - 1,154 1,994 3,358 6,895 11,347 16,372 ($) No. Cars - - 127 528 3,395 12,059 17,941 (1,000 cars) Length of 25,683 27,169 40,244 46,950 56,715 88,775 105,565 Road(km) 3 Population and Size - Seoul-Metropoliotan Area · Regions : Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi · Radius : Seoul City 11~16 km Metro Seoul 4872 km Population Size Density (million) (㎢) (per ㎢) Seoul 10.36 605.3 17,115 Incheon 2.66 1,002.1 2,654 Gyeonggi 11.11 10,183.3 1,091 Total 24.13 11,790.7 2,047 4 III. -

Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-Do & Seoul Metropolitan Area

Gyeongchun line Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-do & Seoul Metropolitan Area Hoeryong Uijeongbu Ganeung Nogyang Yangju Deokgye Deokjeong Jihaeng DongducheonBosan Jungang DongducheonSoyosan Chuncheon Mangwolsa 1 Starting Point Destination Dobongsan 7 Namchuncheon Jangam Dobong Suraksan Gimyujeong Musan Paju Wollong GeumchonGeumneungUnjeong TanhyeonIlsan Banghak Madeul Sanggye Danngogae Gyeongui line Pungsan Gireum Nowon 4 Gangchon 6 Sungshin Baengma Mia Women’s Univ. Suyu Nokcheon Junggye Changdong Baekgyang-ri Dokbawi Ssangmun Goksan Miasamgeori Wolgye Hagye Daehwa Juyeop Jeongbalsan Madu Baekseok Hwajeong Wondang Samsong Jichuk Gupabal Yeonsinnae Bulgwang Nokbeon Hongje Muakjae Hansung Univ. Kwangwoon Gulbongsan Univ. Gongneung 3 Dongnimmun Hwarangdae Bonghwasan Sinnae (not open) Daegok Anam Korea Univ. Wolgok Sangwolgok Dolgoji Taereung Bomun 6 Hangang River Gusan Yeokchon Gyeongbokgung Seokgye Gapyeong Neunggok Hyehwa Sinmun Meokgol Airport line Eungam Anguk Changsin Jongno Hankuk Univ. Junghwa 9 5 of Foreign Studies Haengsin Gwanghwamun 3(sam)-ga Jongno 5(o)-gu Sinseol-dong Jegi-dong Cheongnyangni Incheon Saejeol Int’l Airport Galmae Byeollae Sareung Maseok Dongdaemun Dongmyo Sangbong Toegyewon Geumgok Pyeongnae Sangcheon Banghwa Hoegi Mangu Hopyeong Daeseong-ri Hwajeon Jonggak Yongdu Cheong Pyeong Incheon Int’l Airport Jeungsan Myeonmok Seodaemun Cargo Terminal Gaehwa Gaehwasan Susaek Digital Media City Sindap Gajwa Sagajeong Dongdaemun Guri Sinchon Dosim Unseo Ahyeon Euljiro Euljiro Euljiro History&Culture Park Donong Deokso Paldang Ungilsan Yangsu Chungjeongno City Hall 3(sa)-ga 3(sa)-ga Yangwon Yangjeong World Cup 4(sa)-ga Sindang Yongmasan Gyeyang Gimpo Int’l Airport Stadium Sinwon Airprot Market Sinbanghwa Ewha Womans Geomam Univ. Sangwangsimni Magoknaru Junggok Hangang River Mapo-gu Sinchon Aeogae Dapsimni Songjeong Office Chungmuro Gunja Guksu Seoul Station Cheonggu 5 Yangcheon Hongik Univ. -

The Horticultural Sector in the Republic of Korea

THE HORTICULTURAL SECTOR IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA f- -, " ^ if i m nus 'tA SIGN : L Z* 3 5Tà C3 33 EX. NO, »iQTHEEK MLV: Arnold P. Verhaegh August 1992 Ministry of Agriculture, Agriculture Economics Nature Management and Fisheries Research Institute (LEI) Department for Trade & Industry Horticultural Division P.O. Box 20401 P.O. Box 29703 2500 EK The Hague 2502 LS The Hague The Netherlands The Netherlands \>o; FOREWORD The industrial activities are growing very strong in the Republic of Korea, resulting in a strong increase of the income. Agriculture is not following these developments. Korean government considers the modern horticultural production with emphasis on modern glasshouse production and especially flower growing, as a great potential to improve the welfare in the country. Korean government has far developed plans to import hundreds"^hectares of modern glasshouses with modern equipment. The Dutch greenhouse industry could possibly give support to these developments. On request of the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries, Department for Trade and Industry, Ir. A.P. Verhaegh of the Agricultural Economics Research Institute (AERI) visited Korea from March 30, 1992 till April 12, 1992 to study the Korean horticultural sector. Findings are published in this report. The aim of the study was to analyze the Korean horticultural sector to give more insight in possible cooperation. The Hague, September 15, 1992 Ir. A.P. Verhaegh 2 2 SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 5 GENERAL GEOGRAPHICAL, SOCIOLOGICAL AND -

Choosing the Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing the Right Location

Choosing The Right Location Page 1 of 4 Choosing The Right Location Geography The Korean Peninsula lies in the north-eastern part of the Asian continent. It is bordered to the north by Russia and China, to the east by the East Sea and Japan, and to the west by the Yellow Sea. In addition to the mainland, South Korea comprises around 3,200 islands. At 99,313 sq km, the country is slightly larger than Austria. It has one of the highest population densities in the world, after Bangladesh and Taiwan, with more than 50% of its population living in the country’s six largest cities. Korea has a history spanning 5,000 years and you will find evidence of its rich and varied heritage in the many temples, palaces and city gates. These sit alongside contemporary architecture that reflects the growing economic importance of South Korea as an industrialised nation. In 1948, Korea divided into North Korea and South Korea. North Korea was allied to the, then, USSR and South Korea to the USA. The divide between the two countries at Panmunjom is one of the world’s most heavily fortified frontiers. Copyright © 2013 IMA Ltd. All Rights Reserved. Generated from http://www.southkorea.doingbusinessguide.co.uk/the-guide/choosing-the-right- location/ Tuesday, September 28, 2021 Choosing The Right Location Page 2 of 4 Surrounded on three sides by the ocean, it is easy to see how South Korea became a world leader in shipbuilding. Climate South Korea has a temperate climate, with four distinct seasons. Spring, from late March to May, is warm, while summer, from June to early September is hot and humid. -

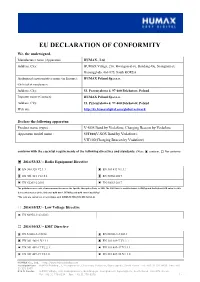

EC Declaration of Conformity

EU DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY We, the undersigned, Manufacturer name (Apparatus) HUMAX., Ltd Address, City: HUMAX Village, 216, Hwangsaeul-ro, Bundang-Gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 463-875, South KOREA Authorized representative name (in Europe): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. (On behalf of manufacturer) Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Importer name (Contact): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Web site http://kr.humaxdigital.com/global-network Declare the following apparatus: Product name (type) : V-SOS Band by Vodafone, Charging Beacon by Vodafone Apparatus model name : VIT100(V-SOS Band by Vodafone), VIT100(Charging Beacon by Vodafone) conform with the essential requirements of the following directives and standards: (Note: ▣ conform, □ Not conform) ▣ 2014/53/EU - Radio Equipment Directive ▣ EN 300 328 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 303 413 V1.1.1 ▣ EN 301 511 V12.5.1 ▣ EN 50566:2017 ▣ EN 62209-2:2010 ▣ EN 50663:2017 The guidelines use a unit of measurement known as the Specific Absorption Rate, or SAR. The SAR limit for mobile devices is 4W/kg and the highest SAR value for this device when tested at the limb was GSM 900 1.567W/kg and GSM 1800 1.922W/kg*. *The tests are carried out in accordance with [CENELEC EN50566] [IEC 62209-2]. □ 2014/35/EU - Low Voltage Directive ▣ EN 60950-1/A2:2013 □ 2014/30/EU - EMC Directive ▣ EN 61000-3-2:2014 ▣ EN 61000-3-3:2013 ▣ EN 301 489-1 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-7 V1.3.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V2.2.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V3.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-19 V2.1.0 ▣ EN 301 489-52 V1.1.0 HUMAX Co., Ltd. -

1997 Conference Program Book (Hangul)

W ELCOME Korea Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages 대한영어교육학회 1997 National Conference and Publishers Exposition Technology in Education; Communicating Beyond Traditional networks October 3-5, 1997 Kyoung-ju Education and Cultural Center Kyoung-ju, South Korea Conference Co-chairs; Demetra Gates Taegu University of Education Kari Kugler Keimyung Junior University, Taegu 1996-97 KOTESOL President; Park Joo-kyung Honam University, Kwangju 1997-98 KOTESOL President Carl Dusthimer Hannam University, Taejon Presentation Selection Committee: Carl Dusthimer, Student Coordination: Steve Garrigues Demetra Gates, Kari Kugler, Jack Large Registration: Rodney Gillett, AeKyoung Large, Jack Program: Robert Dickey, Greg Wilson Large, Lynn Gregory, Betsy Buck Cover: Everette Busbee International Affairs: Carl Dusthimer, Kim Jeong- ryeol, Park Joo Kyung, Mary Wallace Publicity: Oryang Kwon Managing Information Systems: AeKyoung Large, Presiders: Kirsten Reitan Jack Large, Marc Gautron, John Phillips, Thomas Special Events: Hee-Bon Park Duvernay, Kim Jeong-ryeol, Sung Yong Gu, Ryu Seung Hee, The Kyoung-ju Board Of Education W ELCOME DEAR KOTESOL MEMBERS, SPEAKERS, AND FRIENDS: s the 1997 Conference Co-Chairs we would like to welcome you to this year's conference, "Technology Ain Education: Communicating Beyond Traditional Networks." While Korea TESOL is one of the youngest TESOL affiliates in this region of the world, our goal was to give you one of the finest opportunities for professional development available in Korea. The 1997 conference has taken a significant step in this direction. The progress we have made in this direction is based on the foundation developed by the coachers of the past: our incoming President Carl Dusthimer, Professor Woo Sang-do, and Andy Kim. -

Economy & Business in Gyeonggi-Do

[Understanding] The Future of Korea, How Gyeonggi-do Leading the Country more info : www.gyeonggido-korea.com Let's understand about Gyeonggi-do. Not only for Koreans but also people in the world, Gyeonggi-do provides people opportunities and better life. Gyeonggi-do is the province surrounding the capital of South Korea, Seoul. It is the most populated province of Korea having about 13 million inhabitants, more than one-fifth of the entire Korean population. The province has played an important role since 18 BCE when the country was divided into three kingdoms and still plays a vital role for tourism, business, economy and technology in current day South Korea. Economy & Business in Gyeonggi-do Gyeonggi-do is a hub for industry in Korea and ranges from heavy industry (chemical, steel, electronics, machinery) to textile industry, IT, farming, livestock and fisheries. More than a quarter of all Korea’s small and medium-sized companies are located in Gyeonggi-do province and the province is becoming more and more important with the expansion of the Northeast Asian economies. night pangyo Pangyo Techno Valley 1. Gyeonggi-do, the hub of economy and industry Gyeonggi-do lies at the heart of the Korean economy and has the highest GRDP among all other provinces on the South Korean peninsula. Additionally, it has the fastest annual GRDP growth rate in comparison with other provinces and even Seoul Special City. Industry is evenly spread around the province and consists of major companies like Suwon Samsung Semiconductor, Hyundai KIA in Uiwang, Paju's LG Corporation LCD Complex, Icheon's SK Hynix. -

Evaluation and Application of Transit Network Directness Using Geographic Information Systems

Evaluation and Application of Transit Network Directness Using Geographic Information Systems Young-Jae Lee, Ph.D., Associate Professor Department of Transportation and Urban Infrastructure Studies MorganSpeaker State Information University, Title Baltimore, MD [email protected] Jung Yoon Choi, Ph.D. Jeong Whon Yu, Ph.D. Keechoo Choi, Ph.D. Ajou University, Suwon, Korea Transit Performance Measure Points of View (TCRP 88) New Transit Performance Measures - TCRP 88 report has been popular and dominant - However, they are not very specific and general - TCRP Synthesis J-07/Topic SA-43 (Transit Service Evaluation Standards) is in the process - Needs for the more specific and tangible performance measures - Needs for more detailed performance measures for auto/transit travel time Four Transit Network Directness Measures - Degree of Competitiveness: comparison between auto and transit travel times : Total Travel Time Degree of Competitiveness (TTTDOCO) : In-Vehicle Travel Time Degree of Competitiveness (ITTDOCO) - Degree of Circuity: how much the transit service or network configuration can be improved : Total Travel Time Degree of Circuity (TTTDOCI) : In-vehicle Travel Time Degree of Circuity (ITTDOCI) Then - Simple Average - Weighted Average (with demand size) Examples and Analysis Five cities in Korea were selected. - Seoul - Busan - Suwon - Seongnam - Uijeongbu Characters of the Cities City Seoul Busan Suwon Seongnam Uijeongbu Population (million prs) 10.25 3.55 1.09 0.98 0.43 Area (Km2) 605.25 765.64 121.01 141.74 81.59 Population -

Parent Student Handbook

PARENT-STUDENT HANDBOOK 2020-2021 www.siskorea.org 2020-2021 SCHOOL CALENDAR August (14 school days) February (18 school days) S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 11 ES New Students’/Parents’ Orientation 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 Intent Form to Parents HS & MS New Students’/Parents’ 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 11-12 Lunar Holiday (School Closed) Orientation/HS Freshman Orientation 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 15 Deadline for New Applications 12 First Day of School 12:00 p.m. Dismissal 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 22 Deadline for Return of Intent Forms 31 ES/MS Students 12:00 p.m. Dismissal 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 Elementary/Middle School 30 31 Writing Prompt 1 Samil Day (School Closed) September (19 school days) March (19 school days) Faculty Professional Development 3 End of Second Trimester (60 Days) Vision and Mission Statements S M T W T F S S M T W T F S 1 Elementary Open House 8 Re-Enrollment Payment Due for 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Returning Students 2 Middle School Open House 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 3 High School Open House 8 Elementary/Middle School Writing 19 Family Fun Day 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Prompt 28-30 Chuseok Holiday (School Closed) 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 ES/MS Students 12:00 p.m. -

Life Expectancy in Areas Around Subway Stations in the Seoul

J Korean Med Sci. 2020 Nov 16;35(44):e365 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e365 eISSN 1598-6357·pISSN 1011-8934 Original Article Life Expectancy in Areas around Preventive & Social Medicine Subway Stations in the Seoul Metropolitan Area in Korea, 2008–2017 Ikhan Kim ,1,2* Hee-Yeon Kang ,2 and Young-Ho Khang 2,3 1Department of Health Policy and Management, Jeju National University School of Medicine, Jeju, Korea 2Department of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea 3Institue of Health Policy and Management, Seoul National University Medical Research Center, Seoul, Korea Received: Jun 21, 2020 Accepted: Aug 27, 2020 ABSTRACT Address for Correspondence: Background: This study aimed to calculate life expectancy in the areas around 614 subway Young-Ho Khang, MD, PhD stations on 23 subway lines in the Seoul metropolitan area of Korea from 2008 to 2017. Department of Health Policy and Methods: We used the National Health Information Database provided by the National Management, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 103 Daehak-ro, Jongno- Health Insurance Service, which covers the whole population of Korea. The analysis was gu, Seoul 03080, Korea. conducted on the level of the smallest administrative units within a 200-m radius of each E-mail: [email protected] subway station. Life expectancy was calculated by constructing an abridged life table using the number of population and deaths in each area and 5-year age groups (0, 1–4, …, 85+) *Present address: Department of Medical Humanities and Social Medicine, Kosin during the whole study period. -

A Case of Hypertensive Intracerebral Hemorrhage Accompanying Sleep Apnea

online © ML Comm pISSN 2093-9175 / eISSN 2233-8853 BRIEF COMMUNICATION Sleep Med Res 2013;4(2):56-59 A Case of Hypertensive Intracerebral Hemorrhage Accompanying Sleep Apnea Dae Wui Yoon, PhD1, Seung Ku Lee, PhD1, Jin Kwan Kim, PhD2, Chang Ho Yun, MD, PhD3, Seung Hoon Lee, MD, PhD4, Chol Shin, MD, PhD1,5 1Institute of Human Genomic Study, College of Medicine, Korea University Ansan Hospital, Ansan, Korea 2Department of Biomedical Laboratory Science, Jungwon University, Goesan, Korea 3Department of Neurology and Clinical Neuroscience Center, College of Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea 4Department of Otorhinolaryngology, College of Medicine, Korea University Ansan Hospital, Ansan, Korea 5Division of Pulmonary, Sleep and Critical Care Medicine, College of Medicine, Korea University Ansan Hospital, Ansan, Korea Stroke is very common in patients with sleep disordered breathing, especially in the elderly. We report the case of a 26-year-old man who had been referred to us with a sudden left side motor weakness of the body, headache, chronic fatigue, and witnessed sleep apneas. Intracerebral hemorrhage in the right external capsule and putamen was identified upon brain computed tomography. He had hyperten- sion which had not been diagnosed previously. On polysomnography, apnea-hypopnea index was 73.0/h and arousal index was 74.7/h, indicating severe sleep apnea. Continuous positive airway pressure titration was conducted to determine the optimal pressure to allevi- ate the respiratory disturbances. Treatment with antihypertensive medication reduced blood pressure (BP) from 197/145 mm Hg to 130/80 mm Hg after 10 days of use. Co-treatment with the medication and auto-adjustable positive airway pressure additionally de- creased BP to 110/60 mm Hg and normalized respiratory disturbances. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

Operational Environment & Threat Analysis Volume 10, Issue 1 January - March 2019 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED OEE Red Diamond published by TRADOC G-2 Operational INSIDE THIS ISSUE Environment & Threat Analysis Directorate, Fort Leavenworth, KS Topic Inquiries: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Angela Williams (DAC), Branch Chief, Training & Support The Hermit Kingdom .............................................. 3 Jennifer Dunn (DAC), Branch Chief, Analysis & Production OE&TA Staff: North Korea Penny Mellies (DAC) Director, OE&TA Threat Actor Overview ......................................... 11 [email protected] 913-684-7920 MAJ Megan Williams MP LO Jangmadang: Development of a Black [email protected] 913-684-7944 Market-Driven Economy ...................................... 14 WO2 Rob Whalley UK LO [email protected] 913-684-7994 The Nature of The Kim Family Regime: Paula Devers (DAC) Intelligence Specialist The Guerrilla Dynasty and Gulag State .................. 18 [email protected] 913-684-7907 Laura Deatrick (CTR) Editor Challenges to Engaging North Korea’s [email protected] 913-684-7925 Keith French (CTR) Geospatial Analyst Population through Information Operations .......... 23 [email protected] 913-684-7953 North Korea’s Methods to Counter Angela Williams (DAC) Branch Chief, T&S Enemy Wet Gap Crossings .................................... 26 [email protected] 913-684-7929 John Dalbey (CTR) Military Analyst Summary of “Assessment to Collapse in [email protected] 913-684-7939 TM the DPRK: A NSI Pathways Report” ..................... 28 Jerry England (DAC) Intelligence Specialist [email protected] 913-684-7934 Previous North Korean Red Rick Garcia (CTR) Military Analyst Diamond articles ................................................