Seoul Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area

Reformation of Mass Transportation System in Seoul Metropolitan Area 2013. 11. Presenter : Dr. Sang Keon Lee Co-author: Dr. Sang Min Lee(KOTI) General Information Seoul (Area=605㎢, 10mill. 23.5%) - Population of South Korea : 51.8 Million (‘13) Capital Region (Area=11,730㎢, 25mill. 49.4%)- Size of South Korea : 99,990.5 ㎢ - South Korean Capital : Seoul 2 Ⅰ. Major changes of recent decades in Korea Korea’s Pathways at a glance 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Economic Economic Heavy-Chem. Stabilization-Growth- Economic Crisis & Post-war recovery Development takeoff Industry drive Balancing-Deregulation Restructuring Development of Balanced Territorial Post-war Growth pole Regional growth Promotion Industrialization regional Development reconstruction development Limit on urban growth base development Post-war Construction of Highways & National strategic networks Environ. friendly Transport reconstruction industrial railways Urban subway / New technology 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Population 20,189 24,989 31,435 37,407 43,390 45,985 48,580 (1,000 pop.) GDP - 1,154 1,994 3,358 6,895 11,347 16,372 ($) No. Cars - - 127 528 3,395 12,059 17,941 (1,000 cars) Length of 25,683 27,169 40,244 46,950 56,715 88,775 105,565 Road(km) 3 Population and Size - Seoul-Metropoliotan Area · Regions : Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi · Radius : Seoul City 11~16 km Metro Seoul 4872 km Population Size Density (million) (㎢) (per ㎢) Seoul 10.36 605.3 17,115 Incheon 2.66 1,002.1 2,654 Gyeonggi 11.11 10,183.3 1,091 Total 24.13 11,790.7 2,047 4 III. -

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

Construction of Hong-Dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics

Universität Bielefeld Fakultät für Soziologie Construction of Hong-dae Cultural District : Cultural Place, Cultural Policy and Cultural Politics Dissertation Zur Erlangung eines Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Fakultät für Soziologie der Universität Bielefeld Mihye Cho 1. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jörg Bergmann Bielefeld Juli 2007 ii Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Research Questions 4 1.2 Theoretical and Analytical Concepts of Research 9 1.3 Research Strategies 13 1.3.1 Research Phase 13 1.3.2 Data Collection Methods 14 1.3.3 Data Analysis 19 1.4 Structure of Research 22 Chapter 2 ‘Hong-dae Culture’ and Ambiguous Meanings of ‘the Cultural’ 23 2.1 Hong-dae Scene as Hong-dae Culture 25 2.2 Top 5 Sites as Representation of Hong-dae Culture 36 2.2.1 Site 1: Dance Clubs 37 2.2.2 Site 2: Live Clubs 47 2.2.3 Site 3: Street Hawkers 52 2.2.4 Site 4: Streets of Style 57 2.2.5 Site 5: Cafés and Restaurants 61 2.2.6 Creation of Hong-dae Culture through Discourse and Performance 65 2.3 Dualistic Approach of Authorities towards Hong-dae Culture 67 2.4 Concluding Remarks 75 Chapter 3 ‘Cultural District’ as a Transitional Cultural Policy in Paradigm Shift 76 3.1 Dispute over Cultural District in Hong-dae area 77 3.2 A Paradigm Shift in Korean Cultural Policy: from Preserving Culture to 79 Creating ‘the Cultural’ 3.3 Cultural District as a Transitional Cultural Policy 88 3.3.1 Terms and Objectives of Cultural District 88 3.3.2 Problematic Issues of Cultural District 93 3.4 Concluding Remarks 96 Chapter -

Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-Do & Seoul Metropolitan Area

Gyeongchun line Metro Lines in Gyeonggi-do & Seoul Metropolitan Area Hoeryong Uijeongbu Ganeung Nogyang Yangju Deokgye Deokjeong Jihaeng DongducheonBosan Jungang DongducheonSoyosan Chuncheon Mangwolsa 1 Starting Point Destination Dobongsan 7 Namchuncheon Jangam Dobong Suraksan Gimyujeong Musan Paju Wollong GeumchonGeumneungUnjeong TanhyeonIlsan Banghak Madeul Sanggye Danngogae Gyeongui line Pungsan Gireum Nowon 4 Gangchon 6 Sungshin Baengma Mia Women’s Univ. Suyu Nokcheon Junggye Changdong Baekgyang-ri Dokbawi Ssangmun Goksan Miasamgeori Wolgye Hagye Daehwa Juyeop Jeongbalsan Madu Baekseok Hwajeong Wondang Samsong Jichuk Gupabal Yeonsinnae Bulgwang Nokbeon Hongje Muakjae Hansung Univ. Kwangwoon Gulbongsan Univ. Gongneung 3 Dongnimmun Hwarangdae Bonghwasan Sinnae (not open) Daegok Anam Korea Univ. Wolgok Sangwolgok Dolgoji Taereung Bomun 6 Hangang River Gusan Yeokchon Gyeongbokgung Seokgye Gapyeong Neunggok Hyehwa Sinmun Meokgol Airport line Eungam Anguk Changsin Jongno Hankuk Univ. Junghwa 9 5 of Foreign Studies Haengsin Gwanghwamun 3(sam)-ga Jongno 5(o)-gu Sinseol-dong Jegi-dong Cheongnyangni Incheon Saejeol Int’l Airport Galmae Byeollae Sareung Maseok Dongdaemun Dongmyo Sangbong Toegyewon Geumgok Pyeongnae Sangcheon Banghwa Hoegi Mangu Hopyeong Daeseong-ri Hwajeon Jonggak Yongdu Cheong Pyeong Incheon Int’l Airport Jeungsan Myeonmok Seodaemun Cargo Terminal Gaehwa Gaehwasan Susaek Digital Media City Sindap Gajwa Sagajeong Dongdaemun Guri Sinchon Dosim Unseo Ahyeon Euljiro Euljiro Euljiro History&Culture Park Donong Deokso Paldang Ungilsan Yangsu Chungjeongno City Hall 3(sa)-ga 3(sa)-ga Yangwon Yangjeong World Cup 4(sa)-ga Sindang Yongmasan Gyeyang Gimpo Int’l Airport Stadium Sinwon Airprot Market Sinbanghwa Ewha Womans Geomam Univ. Sangwangsimni Magoknaru Junggok Hangang River Mapo-gu Sinchon Aeogae Dapsimni Songjeong Office Chungmuro Gunja Guksu Seoul Station Cheonggu 5 Yangcheon Hongik Univ. -

The Gangnam-Ization of Korean Urban Ideology

Chapter 7 The Gangnam-ization of Korean Urban Ideology Bae-Gyoon Park and Jin-bum Jang 1 Introduction If there is one key word that could characterize contemporary Korean cities, it would be ‘apartments’.1 Single-unit housing was a dominant mode of residence in Korea before the 1980s, but the construction of apartments and multi-unit homes has rapidly increased since then. In particular, the development of mas- sive new towns in the Seoul Metropolitan Area from 1989 onward has triggered a flood in the supply of apartments, ushering in a transition to apartment life for most Koreans. Reflecting on this transformation, Gelézeau (2007) dubs Ko- rea the “apartment republic.” Other scholars have also noted how the sudden apartmentization of the country has shaped middle class cultural life (Park H., 2013) and has led to the virtual destruction of previously existing urban com- munities (Park C., 2013). A second key word that characterizes Korea’s urban transformations is ‘new town’. Through the 1980 Housing Site Development Promotion Act, the Korean state supported the construction of several new towns around the country, including Bundang and Ilsan in the Seoul Metro- politan Area. Facing rapid urbanization and a sharp increase in housing de- mand in some cities, the central government sought to quickly develop a large supply of affordable housing. In 1981, it designated and developed eleven new town sites through the Housing Site Development Promotion Act. By Decem- ber 2016, a total of 617 new towns had been developed through the act, ac- counting for a total of 2.5% of the country’s total land area and 24.4% of its urban housing. -

KSP 7 Lessons from Korea's Railway Development Strategies

Part - į [2011 Modularization of Korea’s Development Experience] Urban Railway Development Policy in Korea Contents Chapter 1. Background and Objectives of the Urban Railway Development 1 1. Construction of the Transportation Infrastructure for Economic Growth 1 2. Supply of Public Transportation Facilities in the Urban Areas 3 3. Support for the Development of New Cities 5 Chapter 2. History of the Urban Railway Development in South Korea 7 1. History of the Urban Railway Development in Seoul 7 2. History of the Urban Railway Development in Regional Cities 21 3. History of the Metropolitan Railway Development in the Greater Seoul Area 31 Chapter 3. Urban Railway Development Policies in South Korea 38 1. Governance of Urban Railway Development 38 2. Urban Railway Development Strategy of South Korea 45 3. The Governing Body and Its Role in the Urban Railway Development 58 4. Evolution of the Administrative Body Governing the Urban Railways 63 5. Evolution of the Laws on Urban Railways 67 Chapter 4. Financing of the Project and Analysis of the Barriers 71 1. Financing of Seoul's Urban Railway Projects 71 2. Financing of the Local Urban Railway Projects 77 3. Overcoming the Barriers 81 Chapter 5. Results of the Urban Railway Development and Implications for the Future Projects 88 1. Construction of a World-Class Urban Railway Infrastructure 88 2. Establishment of the Urban-railway- centered Transportation 92 3. Acquisition of the Advanced Urban Railway Technology Comparable to Those of the Developed Countries 99 4. Lessons and Implications -

Contact Details of the Support Centers for Foreign Workers in the Republic of Korea Name of the Center Region Tel

Contact details of the Support Centers for Foreign Workers in the Republic of Korea Name of the Center Region Tel. Shelter facilities Seoul Migrant Workers Center Seoul 02-3672-9472 ✓ Seoul Migrant Workers House/Korean Chinese Seoul 02-863-6622 ✓ House Sungdong Migrant Workers Center Seoul 02-2282-7974 Elim Mission Center Seoul 02-796-0170 Association for Foreign Migrant Workers Human Seoul 02-795-5504 Rights Yongsan Nanum House Seoul 02-718-9986 ✓ Won Buddism Seoul Foregin Center for Migrant Seoul 02-2699-9943 Workers Migrant Workers Welfare Society Seoul 02-858-4115 With community Migrant Center Gangwon 070-7521-8097 ✓ Osan Migrant Workers Center Osan 031-372-9301 ✓ Pyeongtek Migrant workers Center Pyeongtaek 031-652-8855 ✓ Bucheong Migrant Workers Center Wonmi 032-654-0664 ✓ Korea Migration Foundation Gwanju 031-797-2688 ✓ Cathalic Diocese of Ujeongbu Executive Center Guri 031-566-1142 ✓ EXODUS Gimpo Immigration Center Gimpo 031-982-7661 Anyang immigration Center Anyang 031-441-8502 ✓ Ansan Foreign Workers Support Center 031-4750-111 Ansan Foreign Workers house Ansan 031-495-2288 ✓ Kyungdong Presbyterian Church Pohan 054-291-0191 ✓ Catholic Diocese of Masan Migrant Committee Changwon 055-275-8203 Immigration center Changwon Gumi Maha Migrant Center Gumi 052-458-0755 Sungnam Migrant Workers House/Korean- Kyunggi ,Sung 031-756-2143 Chinese House nam Foreign Workers Cultural Center Gwangju 062-943-8930 ✓ Catholic Social welfare immigrants Pastoral in Gwangju 062-954-8003 ✓ Gwanju Gwnagju Migrant Workers Center Gwangju 062-971-0078 Daejeong -

Korean Conversation FOUNDATION 76 Location 01

Contents 01 03 ABOUT 08 Pyeongtaek at a glance TOURISM 42 Tourist Attractions PYEONGTAEK 09 History of Pyeongtaek PYEONGTAEK 10 Origin of Pyeongtaek / City Environment 10 Location / Climate 04 12 Population / Friendship Cities / Origin of Osan Air Base CULTURAL HERITAGES 50 Cultural Heritage of Pyeongtaek 13 Origin of Camp Humphreys AND HISTORIC SITES 55 Historic Sites of Pyeongtaek 14 City Symbols / Regional product 02 05 GUIDE TO LIVING IN 18 Transportation FESTIVALS AND 60 Festivals PYEONGTAEK 22 Waste EVENTS 64 Good Neighbor Program for USFK and their families 24 Housing 25 Health Insurance 26 Medical Service 06 28 Free Medical Examination for Foreigners KEY 68 Multicultural Support Website 28 Bank Transactions CONTACT SITES 68 Emergency Calls 30 Mobile Phone / Telephone Service 70 Information Calls and Websites 31 High-Speed Internet / Postal Service 71 Useful Applications 32 Electricity / Gas / Water 32 Facilities / Shopping 07 34 Restaurants / Hotels PYEONGTAEK 74 Pyeongtaek International Exchange Foundation 35 Taxes / Keeping public order INTERNATIONAL 75 Our Programs EXCHANGE 36 Let's learn everyday - Korean conversation FOUNDATION 76 Location 01 ABOUT PYEONGTAEK Pyeongtaek at a glance History of Pyeongtaek Origin of Pyeongtaek / City Environment Location / Climate Population / Friendship Cities / Origin of Osan Air Base Origin of Camp Humphreys City Symbols / Regional product 01 ABOUT PYEONGTAEK 01 About Pyeongtaek History of Pyeongtaek The first human presence on Pyeongtaek region can be traced back as far as the Paleolithic Age. By examining other remains of the Paleolithic Age(such as the hunting stones) collected in areas known today as Wonjeong-Ri and the new urban development areas of Cheongbuk-Myeon, it appears that people were present in Pyeongtaek area by the late Paleolithic Age. -

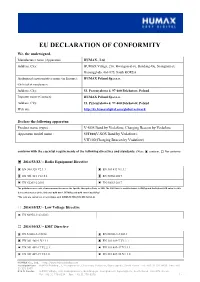

EC Declaration of Conformity

EU DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY We, the undersigned, Manufacturer name (Apparatus) HUMAX., Ltd Address, City: HUMAX Village, 216, Hwangsaeul-ro, Bundang-Gu, Seongnam-si, Gyeonggi-do, 463-875, South KOREA Authorized representative name (in Europe): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. (On behalf of manufacturer) Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Importer name (Contact): HUMAX Poland Sp.z.o.o. Address, City: Ul. Przemyslowa 4, 97-400 Belchatow, Poland Web site http://kr.humaxdigital.com/global-network Declare the following apparatus: Product name (type) : V-SOS Band by Vodafone, Charging Beacon by Vodafone Apparatus model name : VIT100(V-SOS Band by Vodafone), VIT100(Charging Beacon by Vodafone) conform with the essential requirements of the following directives and standards: (Note: ▣ conform, □ Not conform) ▣ 2014/53/EU - Radio Equipment Directive ▣ EN 300 328 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 303 413 V1.1.1 ▣ EN 301 511 V12.5.1 ▣ EN 50566:2017 ▣ EN 62209-2:2010 ▣ EN 50663:2017 The guidelines use a unit of measurement known as the Specific Absorption Rate, or SAR. The SAR limit for mobile devices is 4W/kg and the highest SAR value for this device when tested at the limb was GSM 900 1.567W/kg and GSM 1800 1.922W/kg*. *The tests are carried out in accordance with [CENELEC EN50566] [IEC 62209-2]. □ 2014/35/EU - Low Voltage Directive ▣ EN 60950-1/A2:2013 □ 2014/30/EU - EMC Directive ▣ EN 61000-3-2:2014 ▣ EN 61000-3-3:2013 ▣ EN 301 489-1 V2.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-7 V1.3.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V2.2.1 ▣ EN 301 489-17 V3.1.1 ▣ EN 301 489-19 V2.1.0 ▣ EN 301 489-52 V1.1.0 HUMAX Co., Ltd. -

The Social Construction of Inequality in Gangnam District, Seoul1

Jung In KIM, Matjaž URŠIČ* BESIEGED CITIZENSHIP – THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF INEQUALITY IN GANGNAM DISTRICT, SEOUL1 Abstract. Through an illustrative comparison of squat- ter settlements and gentrified spaces, this study traces the genealogy and formation of extreme poverty at the heart of the most affluent district in Seoul. A site of urban struggle, the villages of Poi and Guryong did not start as spontaneous informal settlements, but as relocated camps of deprivileged social groups whose dislocation was forced by state authorities. After three decades, the Poi and Guryong villages have grown to become contested sites and polar opposites of the hous- ing complex of Tower Place that has is today one of the trendiest neighbourhoods in Seoul. On one hand, the Poi and Guryong villages provide a solid commu- 74 nity space for those displaced, yet one which has now become exceptionally valuable real estate that officials wish to reclaim for new development. The article analy- ses the conflict between residents and entails more than any simple narration of the poor’s disenfranchisement and raises the question of the social construction of ine- qualities and poverty in Seoul. Keywords: squatter settlement, urban development, state planning, Gangnam, citizenship Introduction Modern-day Seoul contains rare and sparsely dispersed enclaves of urban squatters, a few of the last relics of past urbanisation (Cho, 1997; Chung and Lee, 2015; Yonhap, 2017). Paralleling contemporary scenes of urban poverty in East Asia, those urban enclaves of poor people and their everyday life juxtapose manifestations of inequality and injustice against * Jung In Kim, PhD, Professor, Soongsil University, Seoul, South Korea; Matjaž Uršič, PhD, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. -

8. Integrated Energy Supply Program

8. Integrated Energy Supply Program Writer : Korea District Heating & Cooling Association Vice President Tae-Il Han Policy Area: Environment Integrated Energy Supply Program 227 1. General Background & Overview: Integrated Energy Supply in Seoul The supply of integrated energy to apartment complexes in Korea began in Seoul. South Korea is highly dependent on other countries for its energy, and the supply of integrated energy is essential as it promotes energy conservation on a large scale to preserve the environment and reduce the burden on citizens. When the Energy Use Rationalization Act was enacted in 1980, it included stipulations on the supply of inte- grated energy, but the method was very unfamiliar and required prohibitive investment in the early stages, making it impossible for ordinary entities to participate. Being an extremely overpopulated city, Seoul was in dire need of residential apartments and needed to disperse its concentrated population. With the development of new residential land, Seoul became the first city in South Korea to adopt an integrated energy supply. Toward the end of 1982, plans were devised to create a new built-up area in Mok-dong, something which was kept under wraps to prevent real estate speculation, under leadership of the late Kim Jae-ik (killed in the Aung San terror bombing incident), the former Senior Secretary to the President for Economic Affairs. Provision of energy to La Défense (on the outskirts of Paris, France) was used as the benchmark for an inte- grated energy supply model. As Seoul was the first South Korean city to adopt this model, the Ordinance on the Construction & Operation of the Integrated Energy Supply System was passed in 1983, and the Korea Energy Management Corporation (KEMCO), an institution designed to save energy, was commissioned with the task. -

Table of Contents >

< TABLE OF CONTENTS > 1. Greetings .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Company Profile ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 A. Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Status of Registration ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Organization .............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 A. Organization chart ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 B. Analysis of Engineers ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 C. List of Professional Engineers......................................................................................................................................... 10 D. Professional Engineer in Civil Eng.(U.S.A) ..................................................................................................................