Digital Typography & Artificial Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teknik-Grafika-Dan-Industri-Grafika

Antonius Bowo Wasono, dkk. T EKNIK G RAFIKA DAN I NDUSTRI G RAFIKA J ILID 2 SMK Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah Departemen Pendidikan Nasional Hak Cipta pada Departemen Pendidikan Nasional Dilindungi Undang-undang TEKNIK GRAFIKA DAN INDUSTRI GRAFIKA JILID 2 Untuk SMK Penulis : Antonius Bowo Wasono Romlan Sujinarto Perancang Kulit : TIM Ukuran Buku : 17,6 x 25 cm WAS WASONO, Antonius Bowo t Teknik Grafika dan Industri Grafika Jilid 2 untuk SMK /oleh Antonius Bowo Wasono, Romlan, Sujinarto---- Jakarta : Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan, Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, 2008. iii, 349 hlm Daftar Pustaka : Lampiran. A Daftar Istilah : Lampiran. B ISBN : 978-979-060-067-6 ISBN : 978-979-060-069-0 Diterbitkan oleh Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah Departemen Pendidikan Nasional Tahun 2008 KATA SAMBUTAN Puji syukur kami panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT, berkat rahmat dan karunia Nya, Pemerintah, dalam hal ini, Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, telah melaksanakan kegiatan penulisan buku kejuruan sebagai bentuk dari kegiatan pembelian hak cipta buku teks pelajaran kejuruan bagi siswa SMK. Karena buku-buku pelajaran kejuruan sangat sulit di dapatkan di pasaran. Buku teks pelajaran ini telah melalui proses penilaian oleh Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan sebagai buku teks pelajaran untuk SMK dan telah dinyatakan memenuhi syarat kelayakan untuk digunakan dalam proses pembelajaran melalui Peraturan Menteri Pendidikan Nasional Nomor 45 Tahun 2008 tanggal 15 Agustus 2008. Kami menyampaikan penghargaan yang setinggi-tingginya kepada seluruh penulis yang telah berkenan mengalihkan hak cipta karyanya kepada Departemen Pendidikan Nasional untuk digunakan secara luas oleh para pendidik dan peserta didik SMK. -

DNDO Statement of Intent for New National Lab Work, 22 Nov 05

70RDND18R00000001 ER BAA FY18 Exploratory Research in Preventing Nuclear and Radiological Terrorism Broad Agency Announcement No. 70RDND18R00000001 for Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO) Transformational and Applied Research Directorate (TAR) 1 70RDND18R00000001 ER BAA FY18 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................4 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................5 1.2 Grand Challenges & Technology Portfolios ....................................................................6 1.3 Strategic Approach...........................................................................................................8 1.4 Scope and Funding ...........................................................................................................8 2 Exploratory Research Topics ...................................................................................................9 2.1 RTA-01: Mobile Active Interrogation Using Neutrons (MAIN) ....................................9 2.2 RTA-02: Radiation Isotope Identification Device (RIID) Based on Thallium Bromide......................................................................................................................................11 2.3 RTA-03: Nuclear Detection through Centralized Data Analytics .................................14 3 Management Approach ..........................................................................................................16 -

Typeset MMIX Programs with TEX Udo Wermuth Abstract a TEX Macro

TUGboat, Volume 35 (2014), No. 3 297 Typeset MMIX programs with TEX Example: In section 9 the lines \See also sec- tion 10." and \This code is used in section 24." are given. Udo Wermuth No such line appears in section 10 as it only ex- tends the replacement code of section 9. (Note that Abstract section 10 has in its headline the number 9.) In section 24 the reference to section 9 stands for all of ATEX macro package is presented as a literate pro- the eight code lines stated in sections 9 and 10. gram. It can be included in programs written in the If a section is not used in any other section then languages MMIX or MMIXAL without affecting the it is a root and during the extraction of the code a assembler. Such an instrumented file can be pro- file is created that has the name of the root. This file cessed by TEX to get nicely formatted output. Only collects all the code in the sequence of the referenced a new first line and a new last line must be entered. sections from the code part. The collection process And for each end-of-line comment a flag is set to for all root sections is called tangle. A second pro- indicate that the comment is written in TEX. cess is called weave. It outputs the documentation and the code parts as a TEX document. How to read the following program Example: The following program has only one The text that starts in the next chapter is a literate root that is defined in section 4 with the headline program [2, 1] written in a style similar to noweb [7]. -

Accessibility Checklists

Accessibility Checklists www.aub.edu.lb/it May 2020 Contact Person Maha Zouwayhed Office of Information Technology American University of Beirut [email protected] | +961-1-350-000 ext. 2082 Beirut PO Box 11-0236, Riad El Solh 1107 2020, Beirut, Lebanon | Tel: +961-1-350-000 | New York 3 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, 8th Floor | New York, NY 10017–2303, USA | Tel: +1-212-583-7600 | Fax: +1-212-583-7651 1 ACCESSIBILITY CHECKLISTS Role Name & Role Date Compilation Farah Eid – IT Business Development Assistant 13-May-2020 Review Maha Zouwayhed -IT Business Development Manager 14-May-2020 Review Yousif Asfour - CIO (Chief Information Officer) 19-May-2020 Review Walid El-Khazen – Assistant CIO 21-May-2020 Review Ali Zaiter – Senior Software Engineer and Analyst 21-May-2020 Review Fadi Khoury- Manager, Software Development 21-May-2020 Review Rami Farran – Director, It Academic Service 19-May-2020 Review Rana Al Ghazzi – Instructional Designer 19-May-2020 2 ACCESSIBILITY CHECKLISTS Table of Contents Purpose...................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Developers Checklist ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Designers Checklist ................................................................................................................................................ -

Rudolf Hell Zum 100. Geburtstag Hell

„Ich habe nie etwas gemacht nur um Geld zu verdienen. Es ging mir um den Fortschritt und die praktische Anwendung.“ Rudolf Hell Rudolf Hell zum 100. Geburtstag hell Hell Verein / www.hell-kiel.de Im Jahre 2000 konnte die Heidelberger Druckmaschinen AG ihr 150-jähriges Firmenjubiläum feiern. Das Unternehmen, das sich aus den bescheidenen Anfängen einer Schnellpressen- fabrik zum weltweit führenden Anbieter von offenen Lösungen für die Print-Media-Industrie entwickelt hat, wurde im Laufe seiner Geschichte von unterschiedlichen Persönlichkeiten geprägt: Von Dr.-Ing. e.h. Hubert H. A. Sternberg, der mit der konse- Vorwort quenten Konzentration auf die erste vollautomatische Buch- druckmaschine, den Heidelberger Tiegel, den Weg zum größten Druckmaschinenhersteller der Welt vorzeichnete. Von Hugo Brehmer, dem Erfinder der Drahtheftmaschine, der zusammen mit seinem Bruder August in Leipzig eine Buchbindereimaschinen-Fabrik gründete. Leipzig ist auch heute noch einer der Standorte unserer Sparte Druckweiterverar- beitung. Von den Brüdern Alfred und Charles Harris in den USA, die mit der Erfindung eines Anlegers die Druckgeschwindigkeit der damaligen Druckmaschinen verzehnfachen konnten. Aus diesen Anfängen entwickelte sich einer der führenden Hersteller von Rollenoffset-Maschinen, der heute innerhalb der Heidelberg-Gruppe das Solution Center Web vertritt. Von Ottmar Mergenthaler, dem Erfinder der Linotype-Setz- maschine, der die grafische Industrie veränderte, wie rund 560 Jahre zuvor Johannes Gutenberg mit seiner Erfindung der beweglichen Lettern. Und von Dr.-Ing. Rudolf Hell, dessen 100. Geburtstag wir heute feiern dürfen. Diese Festschrift zeigt den Werdegang des Menschen, Ingenieurs und genialen Erfinders Rudolf Hell und die Geschichte des von ihm gegründeten Unternehmens, das wir 1996 als Linotype- Hell AG in die Heidelberg-Familie aufnehmen konnten. -

AWAR Volume 24.Indb

THE AWA REVIEW Volume 24 2011 Published by THE ANTIQUE WIRELESS ASSOCIATION PO Box 421, Bloomfi eld, NY 14469-0421 http://www.antiquewireless.org i Devoted to research and documentation of the history of wireless communications. Antique Wireless Association P.O. Box 421 Bloomfi eld, New York 14469-0421 Founded 1952, Chartered as a non-profi t corporation by the State of New York. http://www.antiquewireless.org THE A.W.A. REVIEW EDITOR Robert P. Murray, Ph.D. Vancouver, BC, Canada ASSOCIATE EDITORS Erich Brueschke, BSEE, MD, KC9ACE David Bart, BA, MBA, KB9YPD FORMER EDITORS Robert M. Morris W2LV, (silent key) William B. Fizette, Ph.D., W2GDB Ludwell A. Sibley, KB2EVN Thomas B. Perera, Ph.D., W1TP Brian C. Belanger, Ph.D. OFFICERS OF THE ANTIQUE WIRELESS ASSOCIATION DIRECTOR: Tom Peterson, Jr. DEPUTY DIRECTOR: Robert Hobday, N2EVG SECRETARY: Dr. William Hopkins, AA2YV TREASURER: Stan Avery, WM3D AWA MUSEUM CURATOR: Bruce Roloson W2BDR 2011 by the Antique Wireless Association ISBN 0-9741994-8-6 Cover image is of Ms. Kathleen Parkin of San Rafael, California, shown as the cover-girl of the Electrical Experimenter, October 1916. She held both a commercial and an amateur license at 16 years of age. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Printed in Canada by Friesens Corporation Altona, MB ii Table of Contents Volume 24, 2011 Foreword ....................................................................... iv The History of Japanese Radio (1925 - 1945) Tadanobu Okabe .................................................................1 Henry Clifford - Telegraph Engineer and Artist Bill Burns ...................................................................... -

TUGBOAT Volume 32, Number 1 / 2011

TUGBOAT Volume 32, Number 1 / 2011 General Delivery 3 From the president / Karl Berry 4 Editorial comments / Barbara Beeton Opus 100; BBVA award for Don Knuth; Short takes; Mimi 6 Mimi Burbank / Jackie Damrau 7 Missing Mimi / Christina Thiele 9 16 years of ConTEXt / Hans Hagen 17 TUGboat’s 100 issues — Basic statistics and random gleanings / David Walden and Karl Berry 23 TUGboat online / Karl Berry and David Walden 27 TEX consulting for fun and profit / Boris Veytsman Resources 30 Which way to the forum? / Jim Hefferon Electronic Documents 32 LATEX at Distributed Proofreaders and the electronic preservation of mathematical literature at Project Gutenberg / Andrew Hwang Fonts 39 Introducing the PT Sans and PT Serif typefaces / Pavel Far´aˇr 43 Handling math: A retrospective / Hans Hagen Typography 47 The rules for long s / Andrew West Software & Tools 56 Installing TEX Live 2010 on Ubuntu / Enrico Gregorio 62 tlcontrib.metatex.org: A complement to TEX Live / Taco Hoekwater 68 LuaTEX: What it takes to make a paragraph / Paul Isambert 77 Luna — my side of the moon / Paweł Jackowski A L TEX 83 Reflections on the history of the LATEX Project Public License (LPPL)— A software license for LATEX and more / Frank Mittelbach 95 siunitx: A comprehensive (SI) units package / Joseph Wright 99 Glisterings: Framing, new frames / Peter Wilson 104 Some misunderstood or unknown LATEX2ε tricks III / Luca Merciadri A L TEX 3 108 LATEX3 news, issue 5 / LATEX Project Team Book Reviews 109 Book review: Typesetting tables with LATEX / Boris Veytsman Hints & Tricks -

SPECIMEN LA BOLDE VITA 1 / 131 ZIMULA ZIMULA ZIMULA ZIMULA ABOUT the TYPEFACE LA BOLDE VITA 2 / 131 Inktrap & Inkspot

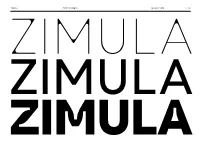

ZIMULA TYPE SPECIMEN LA BOLDE VITA 1 / 131 ZIMULA ZIMULA ZIMULA ZIMULA ABOUT THE TYPEFACE LA BOLDE VITA 2 / 131 InkTrap & InkSpot Zimula is a classic contemporary geometric typeface and TYPEFACE comes in a friendly and warm vibe. With 9 weights ranging Zimula from Thin to Black, the standard styles can be used as a WEIGHTS workhorse for everyday design tasks. Thin, ExtraLight, Light, Regular, Medium, SemiBold, Bold, But the Zimula family comes in two other styles: InkTrap and ExtraBold, Black InkSpot. The former features generous, angular Inktraps, which ensure crisp text in smaller sizes and become a stylis- STYLES tic element in the heavier weights, perfect for catching titles InkTrap, Standard, InkSpot and posters. The latter, on the other hand, fill out the joints, DESIGNED BY resulting in an irregular texture for the lighter weights and a Fabian Dornhecker soft overall appearance for the heavier weights. With the available variable font, you can choose between YEAR OF RELEASE InkTrap and InkSpot seamlessly — this opens up options 2021 for optimizing body copy and finding just the right amount AVAILABLE ON of character for large-format designs. A generous charac- La Bolde Vita ter set, extensive OpenType features and an alternative set → www.laboldevita.com with filled-in punches come on top. ZIMULA OPENTYPE-FEATURES LA BOLDE VITA 3 / 131 STYLISTIC SET 01 (Single-storey a) ▶ SS01 Cutter PRETTY → Cutter PRETTY Mariah@támbien.it → Mariah@támbien.it DYNAMIC FRACTIONS ▶ FRAC STYLISTIC SET 02 (Alternative G) ▶ SS02 41/23 = 1,782 → 47/23 -

PDF Specimen Download

Pensum a monster for text, text and nothing but text — 18 sharp ’n’ soft serif fonts by Nils Thomsen www.typemates.com Pensum Pro · by TypeMates Page 2 ensum is a typeface for text, text and nothing but text. A pure monster, straight and plain. It will set reliably word for word, line for line and paragraph for paragraph, sometimes a spark of the sexy, curvy and strongly ink trapped italic Psneaks into proceedings but anyhow the plain workhorse will keep on setting text. Deep inside some sharp details are hidden unlike some brushy and smooth shapes to be revealed in large sizes. But seriously … Pensum comes along with nine weights from thin to black plus italics. The strong serifs combined with the low contrast makes it excellent for long reading text for example in magazines and books. The extreme thin and fragile styles can give a stylish and fash- ionable look, while the strong black weights are great for the rough nature of mountain sports. Pensum counts around 1050 glyphs including lots of OpenType Features to full fill every typo- — sexy, curvy and graphical need. Most important for lovers of book typography, the strongly ink trapped small-caps are slightly wider than the caps. You will find punctuation italic shapes — in case- and small cap-sensitive variations. The Adobe Latin 3 encoding is a TypeMates standard and gives a wide range of flexibility for Latin language support. Pensum is broad-nib based and inspired by some handwritten brush exercises at Peter Verheuls class during Type and Media course 2009 in The Hague. -

Type & Typography

Type & Typography by Walton Mendelson 2017 One-Off Press Copyright © 2009-2017 Walton Mendelson All rights reserved. [email protected] All images in this book are copyrighted by their respective authors. PhotoShop, Illustrator, and Acrobat are registered trademarks of Adobe. CreateSpace is a registered trademark of Amazon. All trademarks, these and any others mentioned in the text are the property of their respective owners. This book and One- Off Press are independent of any product, vendor, company, or person mentioned in this book. No product, company, or person mentioned or quoted in this book has in any way, either explicitly or implicitly endorsed, authorized or sponsored this book. The opinions expressed are the author’s. Type & Typography Type is the lifeblood of books. While there is no reason that you can’t format your book without any knowledge of type, typography—the art, craft, and technique of composing and printing with type—lets you transform your manuscript into a professional looking book. As with writing, every book has its own issues that you have to discover as you design and format it. These pages cannot answer every question, but they can show you how to assess the problems and understand the tools you have to get things right. “Typography is what language looks like,” Ellen Lupton. Homage to Hermann Zapf 3 4 Type and Typography Type styles and Letter Spacing: The parts of a glyph have names, the most important distinctions are between serif/sans serif, and roman/italic. Normal letter spacing is subtly adjusted to avoid typographical problems, such as widows and rivers; open, touching, or expanded are most often used in display matter. -

David Glen Smith

David Glen Smith Fonts of Influence My intentions are to merge a thick poster font with a thinner sans serif in order to produce a Charlesworth {Charlemagne} modern letter. I hope to shift a traditional-based SPHINX OF BLACK QUARTZ JUDGE MY VOW. character into a more fluid, rounded form. (THERE ARE NO LOWERCASE CHARACTERS) The curved letters would be influenced by leaf shapes: curves, barbs, angles all which appear Poster Bodini in nature with radical variation on a simple SPHINX OF BLACK QUARTZ JUDGE MY VOW form. Which will leave room for improvisation as the font progresses. the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog Likewise I want to incorporate an sense of hand Helvetica Neue drawn images to allow more creative energy and individualism. SPHINX OF BLACK QUARTZ JUDGE MY VOW the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog In the end I would like to use the new version for headers on a developing web site promoting tradional art in diverse manner. Gill Sans SPHINX OF BLACK QUARTZ JUDGE MY VOW the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog Font History • Gill Sans • Charlemagne Designer: Eric Gill of United Kingdom The Charlemagne font was designed by Carol Twombly and inspired Born: Brighton, 1882 Died: Uxbridge, 1940 by the 10th century Carolingian manuscripts. Charlemagne has a strong stress and extended serifs that give the capital letters of the Eric Gill studied under the renowned calligrapher, Edward John- font a distinctive charm which can be successfully exploited in adver- son, the designer of the London Underground sans serif typeface. -

Digital Typography and Artificial Intelligence

Peter Karow, Hamburg Digital Typography and Artificial Intelligence When did typefaces become digital? The target in 1972 : Automation of Photo Typesetting Our desktop in 1974 Our “PC” in 1980 50 M B m ass storage 2 .5 M B disks 2 m e t e r s h i g h First Ikarus brochure, Warsaw 1975 Digital Typefaces 1. Formats 2. Variations 3. Interpolation 4. Rasterizing 5. Hinting 6. Autotracing 7. Grayscaling 8. Element separation Subjects of digitizing Results Bitmap (left) Run length (middle) Vector (right) PostScript (left) Elements (middle) Metafont (right) Digital Typefaces 1. Formats 2. Variations 3. Interpolation 4. Rasterizing 5. Hinting 6. Autotracing 7. Grayscaling 8. Element separation Range of Variations 1. Continuous Enlarging 2. Contouring 3. Italizing (not Slanting) 4. Expanding/Condensing 5. Rounding 6. Shadowing 7. Antiquing In 1973, the first variations of typefaces were calculated as such: contouring and shadowing It was the birth of digital typefaces. Contouring The font “Ice Age” with variations Digital Typefaces 1. Formats 2. Variations 3. Interpolation 4. Rasterizing 5. Hinting 6. Autotracing 7. Grayscaling 8. Element separation Interpolation of hybrids Digital Typefaces 1. Formats 2. Variations 3. Interpolation 4. Rasterizing 5. Hinting 6. Autotracing 7. Grayscaling 8. Element separation Typical accidents from rasterizing (left) Various resolutions Digital Typefaces 1. Formats 2. Variations 3. Interpolation 4. Rasterizing 5. Hinting 6. Autotracing 7. Grayscaling 8. Element separation Basic hints in 1985 17 hints after the first refinements in 1987 Digital Typefaces 1. Formats 2. Variations 3. Interpolation 4. Rasterizing 5. Hinting 6. Autotracing 7. Gray scaling 8. Element separation Autotracing has to recognize at least the following elements: Digital Typefaces 1.