Techology and Innovation 10/01/2006 10:24 AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Look Back at the Personal Computer's First Decade—1975 To

PROFE MS SSI E ON ST A Y L S S D A N S A S O K C R I A O thth T I W O T N E N 20 A Look Back at the Personal Computer’s First Decade—1975 to 1985 By Elizabeth M. Ferrarini IN JANUARY 1975, A POPULAR ELECTRONICS MAGAZINE COVER STORY about the $300 Altair 8800 kit by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry PC TRIVIA officially gave birth to the personal computer (PC) industry. It came ▼ Bill Gates and Paul Allen wrote the first Microsoft BASIC with two boards and slots for 16 more in the open chassis. One board for the Altair 8800. held the Intel 8080 processor chip and the other held 256 bytes. Other ▼ Steve Wozniak hand-built the first Apple from $20 worth PC kit companies included IMSAI, Cromemco, Heathkit, and of parts. In 1985, 200 Apple II's sold every five minutes. Southwest Technical Products. ▼ Initial press photo for the IBM PC showed two kids During that same year, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak created the sprawled on the living room carpet playing games. The ad 4K Apple I based on the 6502 processor chips. The two Steves added was quickly changed to one appropriate for corporate color and redesign to come up with the venerable Apple II. Equipped America. with VisiCalc, the first PC spreadsheet program, the Apple II got a lot ▼ In 1982, Time magazine's annual Man of the Year cover of people thinking about PCs as business tools. This model had a didn't go to a political figure or a celebrity, but a faceless built-in keyboard, a graphics display, and eight expansion slots. -

Exploring Users' Perceptions and Expectations of Security

Cloudy with a Chance of Misconceptions: Exploring Users’ Perceptions and Expectations of Security and Privacy in Cloud Office Suites Dominik Wermke, Nicolas Huaman, Christian Stransky, Niklas Busch, Yasemin Acar, and Sascha Fahl, Leibniz University Hannover https://www.usenix.org/conference/soups2020/presentation/wermke This paper is included in the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security. August 10–11, 2020 978-1-939133-16-8 Open access to the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security is sponsored by USENIX. Cloudy with a Chance of Misconceptions: Exploring Users’ Perceptions and Expectations of Security and Privacy in Cloud Office Suites Dominik Wermke Nicolas Huaman Christian Stransky Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Niklas Busch Yasemin Acar Sascha Fahl Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Abstract respective systems. These dedicated office tools helped the Cloud Office suites such as Google Docs or Microsoft Office adoption of personal computers over more dedicated or me- 365 are widely used and introduce security and privacy risks chanical systems for word processing. In recent years, another to documents and sensitive user information. Users may not major shift is happening in the world of office applications. know how, where and by whom their documents are accessible With Microsoft Office 365, Google Drive, and projects like and stored, and it is currently unclear how they understand and LibreOffice Online, most major office suites have moved to mitigate risks. We conduct surveys with 200 cloud office users provide some sort of cloud platform that allows for collabo- from the U.S. -

EPROM Programmer for the Kaypro

$3.00 June 1984 TABLE OF CONTENTS EPROM Programmer for the Kaypro .................................. 5 Digital Plotters, A Graphic Description ................................ 8 I/O Byte: A Primer ..................................................... .1 0 Sticky Kaypros .......................................................... 12 Pascal Procedures ........................................................ 14 SBASIC Column ......................................................... 18 Kaypro Column ......................................................... 24 86 World ................................................................ 28 FOR1Hwords ........................................................... 30 Talking Serially to Your Parallel Printer ................................ 33 Introduction to Business COBOL ...................................... 34 C'ing Clearly ............................................................. 36 Parallel Printing with the Xerox 820 .................................... 41 Xerox 820, A New Double.. Density Monitor .......................... 42 On 'Your Own ........................................................... 48 Technical Tips ........................................................... 57 "THE ORIGINAL BIG BOARD" OEM - INDUSTRIAL - BUSINESS - SCIENTIFIC SINGLE BOARD COMPUTER KIT! Z-80 CPU! 64K RAM! (DO NOT CONFUSE WITH ANY OF OUR FLATTERING IMITATORSI) .,.: U) w o::J w a: Z o >Q. o (,) w w a: &L ~ Z cs: a: ;a: Q w !:: ~ :::i ~ Q THE BIG BOARD PROJECT: With thousands sold worldwide and over two years -

The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation

Remembering the Office of the Future: The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation Thomas Haigh University of Wisconsin Word processing entered the American office in 1970 as an idea about reorganizing typists, but its meaning soon shifted to describe computerized text editing. The designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies to exploit the falling costs of interactive computing, creating a new business quite separate from the emerging world of the personal computer. Most people first experienced word processing using a word processor, we think of a software as an application of the personal computer. package, such as Microsoft Word. However, in During the 1980s, word processing rivaled and the early 1970s, when the idea of word process- eventually overtook spreadsheet creation as the ing first gained prominence, it referred to a new most widespread business application for per- way of organizing work: an ideal of centralizing sonal computers.1 By the end of that decade, the typing and transcription in the hands of spe- typewriter had been banished to the corner of cialists equipped with technologies such as auto- most offices, used only to fill out forms and matic typewriters. The word processing concept address envelopes. By the early 1990s, high-qual- was promoted by IBM to present its typewriter ity printers and powerful personal computers and dictating machine division as a comple- were a fixture in middle-class American house- ment to its “data processing” business. Within holds. Email, which emerged as another key the word processing center, automatic typewriters application for personal computers with the and dictating machines were rechristened word spread of the Internet in the mid-1990s, essen- processing machines, to be operated by word tially extended word processing technology to processing operators rather than secretaries or electronic message transmission. -

CP/M-80 Kaypro

$3.00 June-July 1985 . No. 24 TABLE OF CONTENTS C'ing Into Turbo Pascal ....................................... 4 Soldering: The First Steps. .. 36 Eight Inch Drives On The Kaypro .............................. 38 Kaypro BIOS Patch. .. 40 Alternative Power Supply For The Kaypro . .. 42 48 Lines On A BBI ........ .. 44 Adding An 8" SSSD Drive To A Morrow MD-2 ................... 50 Review: The Ztime-I .......................................... 55 BDOS Vectors (Mucking Around Inside CP1M) ................. 62 The Pascal Runoff 77 Regular Features The S-100 Bus 9 Technical Tips ........... 70 In The Public Domain... .. 13 Culture Corner. .. 76 C'ing Clearly ............ 16 The Xerox 820 Column ... 19 The Slicer Column ........ 24 Future Tense The KayproColumn ..... 33 Tidbits. .. .. 79 Pascal Procedures ........ 57 68000 Vrs. 80X86 .. ... 83 FORTH words 61 MSX In The USA . .. 84 On Your Own ........... 68 The Last Page ............ 88 NEW LOWER PRICES! NOW IN "UNKIT"* FORM TOO! "BIG BOARD II" 4 MHz Z80·A SINGLE BOARD COMPUTER WITH "SASI" HARD·DISK INTERFACE $795 ASSEMBLED & TESTED $545 "UNKIT"* $245 PC BOARD WITH 16 PARTS Jim Ferguson, the designer of the "Big Board" distributed by Digital SIZE: 8.75" X 15.5" Research Computers, has produced a stunning new computer that POWER: +5V @ 3A, +-12V @ 0.1A Cal-Tex Computers has been shipping for a year. Called "Big Board II", it has the following features: • "SASI" Interface for Winchester Disks Our "Big Board II" implements the Host portion of the "Shugart Associates Systems • 4 MHz Z80-A CPU and Peripheral Chips Interface." Adding a Winchester disk drive is no harder than attaching a floppy-disk The new Ferguson computer runs at 4 MHz. -

Published In: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), Pp

Published in: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), pp. 268-78 Author’s address: [email protected] WORD PROCESSING (HISTORY OF). Definition. The term and concept of “word processing” are by now so widely used that most readers will be already familiar with them. The term, created on the model of “data processing,” is more vague than commonly believed. A human editor, for example, obviously pro- cesses words, but is not what is meant by a “word proces- sor.” A number of software programs process words in one way or another--a concordance or indexing program, for example--but are not understood to be word processing programs.’ The term “word processor” means a facility that records keystrokes from a typewriter-like keyboard, and prints the output onto paper in a separate operation. In the meantime the data is stored, usually in memory or mag- netic media. A word processor also can make improve- ments in the stream of words before they are printed. At their most basic these include the ability to arrange words into lines. An “editor,” such as the infamous EDLINE distributed with the Microsoft Disk Operating System (MS-DOS), lacks the ability to structure lines. Commonly a word processor is understood to be a software program, and in the 1980s and 1990s it usually meant a program written for a microcomputer. However, preceding this period and continuing through it there have been hardware word processors. These are pieces of equip- ment sold for the sole purpose of word processing, con- taining in one package a keyboard, printer, recording and playback device, and in all recent examples a video or liquid crystal display screen. -

Instructions to the Students: Outlines: Understanding Word Processing Program

Karary University – Dr. Abdeldime Mohamed Salih – Lecture Note College of Medicine Lecture Two Title: Dealing With Word Processing Programs Instructions to the Students: By the end of this lecture readers will be familiar with Microsoft word usages. Before start: You need to use your own computer to practice the following skills The following note is prepared to understanding how to deal with the computer in general. Further information can be found at the reference given in the content of the subject. Also you can find more information in the internet. The content is prepared in such way that suits the pharmacy college students to help them dealing with Microsoft word. Also you contact the instructor in his office any time between 12:00 to 2:00 Word processing programs are constantly evolving. Try to keep as up-to-date as possible by reading computer-related news, blogs, RSS feeds, newsletters, forums, and following computer people on social networking sites. Micrsoft word is a very good tool for word processing and editing documents and has many properties that would help and you need to practice, practice, and practice! Outlines: 1. Understanding word processing Program 2. Word Processing Programs 3. Microsoft word 4. Some tips for saving time when using Microsoft word 5. Some exercises Understanding word processing Program In the past, the word processor was a device that provides for formatting and output of text, often with some additional features. Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to this function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers to input, editing, formatting text. -

MOVE-IT (Tin) User's Manual

TM EWTER-CQMPOTER COJWIWUMICATIORf SYSTEM t I USERS MANUAL WOOLF SOFTV/ARE SYSTEMS *,. 23842 ARCHWOOD ST., CANOGA PARK, CA 81307 PHONE (213) 703-6112 COPYRIGHT 1982. ALL RIGHTS REScfVED. MOVE-IT (tm) OSER'S MANUAL - For version 3.0 November, 1982 Copyright 1982 WOOLP SOFTWARE SYSTEMS All rights reserved « • I ——> Preliminary Version <• s No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or by any means transcribed without the prior written permission of WOOLF SOFT- WARE SYSTEMS, 23842 Archwood St. Canoga Park, CA 91307. WOOLF SOFTWARE SYSTEMS makes no representations or warranties, written or otherwise, with respect to the contents hereof. Further, WOOLF SOFTWARE SYSTEMS reserves the right to revise this publication without obligation or WOOLF SOFTWARE SYSTEMS to notify any person(s) of sucn revision. TABLE OP CONTENTS n Page 1. LICENSE AGREEMENT 1 ji 2. NOTATION USED IN THIS MANUAL 4 { i 3. INTRODUCTION 5 } 4. COMMANDS 7 ! The Send Command ........... 8 ; The Get Command 10 ; The Noconsole Command . .11 '• The Ascii Command ........... 12 ; The Binary Command 13 ;j The Call Command 14 t; Creating an Auto-dial Directory. 15 \\ The Hangup Command . 16 / The Answer Command .......'... 17 •; The Ldir Command 18 :| The Rdir Command . 19 ! The Luser Command 20 3 The Ruser Command . 21 • The Message Command 22 The Tries Command 23 i The Talk Command 24 ** Getting help in Talk Mode ..... 24 i Sending files 25 • ... Getting files 26 -.- Toggling file trapping 27 Auto Linefeed 27 • Remote Echo . 27 Toggling the Printer 27 Modifying XON and XOFF chars . 28 Exiting Talk Mode 28 Exiting Move-it 29 Getting help - the ? command .... -

Uniform for the Additional Improve Readability, Although the Blanks Are Not Necessary

User's Guide IBM Personal Computer and Compatible Version Preface Congratulations on your decision to purchase UniForm. It will open new avenues of communication between your Computer and many others, giving you the ability to exchange diskettes füll of Information with people using other types of Computers. We think you'll agree that UniForm is one of the best additions you've ever rnade to your Computer System. UniForm allows you to redefine the Operating forrnat of one of your floppy disk drives. You manipulate the data on the diskette with the tools you normally use: word processors, file transfer Utilities, or other pro- grams. UniForm is Invisible to you when it is in use. This manual assumes that you have a basic working knowledge of your Computer System and the programs you will be using. If you have not yet learned to use COPY (for copying files between diskettes) and CHKDSK (for checking how much room is left on a diskette), you should read your DOS manuals and use a practice diskette to learn the basics of them. Once you know the basics, you can move on to UniForm. This User's guide will provide practical examples to Supplement the self-prompting menus of UniForm. If you want to know more about what First Edition (October 1984) UniForm does, read the introduction, which follows. When you're ready Copyright © 1984 by Micro Solutions, Inc. to start using UniForm, take just a moment to read about the conven- tions; then you'll quickly be on your way. Micro Solutions, Inc. -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

UTILITIES PRINT Mp 1117 17511Y~R1 T SERIAI MT N IT,11

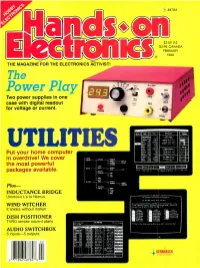

11 48784 $2.50 U.S. $2.95 CANADA FEBRUARY 1 ?88 THE MAGAZINE FOR THE ELECTRONICS ACTIVIST! The _ )0. Power Play ON ! Two power supplies in one 410 OFF NE ; case with digital readout G for voltage or current. SIDEC um.- NI PIS1110 ERI 11.11 UI/. 711KIS2 PIP :Ia 11 U.rr Isles (OPIMI (On 25717 2101111 1,1t.. INt PICT SPL I I/N/ MII71 kort .,Ad EDITOR p1 177721 11151111101 1.lrt tOt1 L«l;l lit NERI MI 7175 Atli SPL 7772 LONG AL? 191577 A. UTILITIES PRINT mP 1117 17511y~r1 t SERIAI MT N IT,11. bytes ..r1 Put your home computer SPELL Vol 22172 455768 19t.. fetal STARVI I17 112 TIOVE-1 11 IIIIS ...Niel 1. ... 1 .K/TREE YEK 725152 11 3M TIMIIIY011 Ldlri1 in We cover . LETTERS overdrive! POI /PIOC 11.,1.1 - 0111 041 22711 ÈUQIOIE REPLIES 1:16.. GOV.. ACTION the most powerful PERSONAL Ente cow I TYP. I C... =PMdEwa MI ht. I T. - SHIERS ,r packages available. - C rat 110. C. - OUI, Auno - 11(0115 Plus - INDUCTANCE BRIDGE 11.1 V1[ Unknown Ls to Henrys (..1_.u1..I01l.I lrt 1.. Set 11J V1. S..<1.1 Prut fete 0.01 T1 .r.M..l Doi On /rot. (.M ti01 it Prr..ltuY.N lee .. IF". WIND WITCHER .r <t1. <.y.l4l. pot. Tl.. 0.01 1..1yI.M 1!... ..I.tN .1t1 t011 ..1 011ry ,01 r1 .<1.,t .Y 1r 01 11 It tinkles without motion Ir (.L. 2747,1,11 15,27113,01 27,/Y21M4 274141,1 27,71444 DISH POSITIONER 27045,144 2704(711,1 1111 r TVRO remote move -it plans w.1I.,r4 .r. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 269 639 CE 044 490 Welcome to the World of Computers. Part 2. Education Service Center Region 20, San Antonio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 269 639 CE 044 490 TITLE Welcome to the World of Computers. Part 2. INSTITUTION Education Service Center Region 20, San Antonio, Tex. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 311p.; For part 1, see CE 044 489. T'ortions of reprinted material contain small or broken type. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adult Education; Classroom Techniques; Computer Assisted Instruction; *Computer Literacy; *Computer Oriented Programs; *Computer Software; Databases; Integrated Curriculum; *Learning Activities; *Microcomputers; Postsecondary Education; Program Evaluation; Word Processing IDENTIFIERS BASIC Programing Language; Spreadsheets ABSTRACT A continuation of an earlier manual, this guidewas written to help adult education teachers and their studentsto go beyond the information of part 1 and learnmore about the uses of computers. Although this manual is directed more toward teachers and administrators than toward students, activities for studentsare provided. As in part 1, some of the manual has been writtenso that instruction can be given with or witIouta computer; it can be used in a computer literacy class or as part ofa class in some other area, such as English oz mathematics. This manual is organized in six sections. The first five sections cover the following topics: computer review; software applications (word processing, database, spreadsheets, and BASIC programming); evaluation of software (including an annotated resource guide anda software buyer's guide), graphics, and computer-assisted instruction. Each sectioncontains information (including reprints of materials froma variety of sources), learning activities for students, and test items. Materials are illustrated with line drawings. The final section contains reprints of brief articles about computer literacy.