Hungarian Studies Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Attitudes Toward Charity: the Values of Depression-Era America As Reflected in Its Literature

CHANGING ATTITUDES TOWARD CHARITY: THE VALUES OF DEPRESSION-ERA AMERICA AS REFLECTED IN ITS LITERATURE By Steven M. Stary As a time of economic and political crisis, the Great Depression influenced authors who VRXJKWWRUHZULWH$PHULFD¶VXQGHUO\LQJmythology of rugged individualism into one of cooperative or communal sensibility. Through their creative use of narrative technique, the authors examined in this thesis bring their readers into close identification with the characters and events they describe. Creating connection between middle-class readers and the destitute subjects of their works, the authors promoted personal and communal solutions to the effects of the Depression rather than the impersonal and demeaning forms of charity doled out by lRFDOJRYHUQPHQWVDQGSULYDWHFKDULWLHV0HULGHO/H6XHXU¶V DUWLFOHV³:RPHQRQWKH%UHDGOLQHV´³:RPHQDUH+XQJU\´DQG³,:DV0DUFKLQJ´ DORQJZLWK7RP.URPHU¶VQRYHOWaiting for Nothing, are examined for their narrative technique as well as depictions of American attitudes toward charitable giving and toward those who receive charity. The works of Le Sueur and Kromer are shown as a SURJUHVVLRQFXOPLQDWLQJLQ-RKQ6WHLQEHFN¶VThe Grapes of Wrath later in the decade. By the end of the 1930s significant progress had been made in changing American values toward communal sensibility through the work of these authors and the economic programs of the New Deal, but the shift in attitude would not be completely accomplished or enduring. To my wife, Dierdra, who made it possible for me to keep on writing, even though it took longer than I thought it would. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to Dr. Don Dingledine, my thesis advisor, who has helped to see this work to completion. It is due to his guidance this project has its good points, and entirely my fault where it does not. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

Generic Experiment and Confusion in Early Canadian Novels of the Great War

Generic Experiment and Confusion in Early Canadian Novels of the Great War Colin Hill he Canadian novel changed dramatically in the years immediately following the Great War of 1914-18. In the 1920s and ’30s an innovative, modern, cosmopolitan, and multi-gen- ericT literary realism began to challenge and supersede the nineteenth- century romanticism that had loomed large in the national fiction at least since Confederation. Two formative literary magazines were found- ed shortly after the 1918 armistice: Canadian Bookman in 1919 and The Canadian Forum in 1920. Both publications printed articles and mani- festos that demanded a new realism capable of representing the modern and independent Canada that had emerged from the war. In these same years, Canadian writers from all regions began to produce modern-real- ist novels in various sub-genres, including prairie realism, urban realism, and social realism. These writers challenged the verbose and ornate styles of their predecessors with a language that was idiomatic and dir- ect. They sought narrative objectivism and impersonality in accordance with the documentary approach they brought to their representations of contemporary Canada. The most ambitious and creative modern realists experimented with literary form and reworked innovative and international modernist devices to express their interest in exploring and representing human psychology. By the end of the 1920s, some of the best examples of these multi-generic modern-realist works had been published, and a few of them are still read today: J.G. Sime’s Sister Woman (1919), Douglas Durkin’s The Magpie (1923), Frederick Philip Grove’s Settlers of the Marsh (1925), Martha Ostenso’s Wild Geese (1925), Morley Callaghan’s Strange Fugitive (1928), and Raymond Knister’s White Narcissus (1929). -

Hungarian Studies Review, 29, 1-2 (1992): 7-27

A Communist Newspaper for Hungarian-Americans: The Strange World of the Uj Elore Thomas L. Sakmyster On November 6, 1921 the first issue of a newspaper called the Uj Elore (New Forward) appeared in New York City.1 This paper, which was published by the Hungarian Language Federation of the American Communist Party (then known as the Workers Party), was to appear daily until its demise in 1937. With a circulation ranging between 6,000 and 10,000, the Uj Elore was the third largest newspaper serving the Hungarian-American community.2 Furthermore, the Uj Elore was, as its editors often boasted, the only daily Hungarian Communist newspaper in the world. Copies of the paper were regularly sent to Hungarian subscri- bers in Paris, Berlin, Vienna, Moscow, Buenos Aires, and, on occasion, even smuggled into Budapest. The editors and journalists who produced the Uj Elore were a band of fervent ideologues who presented and inter- preted news in a highly partisan and utterly dogmatic manner. Indeed, this publication was quite unlike most American newspapers of the time, which, though often oriented toward a particular ideology or political party, by and large attempted to maintain some level of objectivity. The main purpose of Uj Elore, as later recalled by one of its editors, was "not the dissemination of news but agitation and propaganda."3 The world as depicted by writers for the Uj Elore was a strange and distorted one, filled with often unintended ironies and paradoxes. Readers of the newspaper were provided, in issue after issue, with sensational and repetitive stories about the horrors of capitalism and fascism (especially in Hungary and the United States), the constant threat of political terror and oppression in all countries of the world except the Soviet Union, and the misery and suffering of Hungarian-American workers. -

The Universite of Oklahoma Graduate College M

THE UNIVERSITE OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE M ANALYSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS’ U.S.A. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHE BE F. UILLIAIl NELSON Norman, Oklahoma 1957 All ANALÏSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS' U.S.A. APPROVED 3Ï ijl^4 DISSERTATION COmTTEE TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. THE CRITICS....................................... 1 II. THE CAST .......................................... III. CLOSE-UP .......................................... ho IV. DOCUMENTARY ....................................... 63 V. MONTAGE........................................... 91 VI. CROSS-CUTTING ...................................... Il4 VII. SPECIAL EFFECTS .................................... 13o VIII. WIDE ANGLE LENS .................................... l66 IX. CRITIQUE .......................................... 185 APPENDK ................................................. 194 BIBLIOGRAPHY ............................................. 245 111 ACKNOWLEDGEI'IENT Mjr thanks are due all those members of the Graduate Faculty of the Department of English who, knowingly and unknowingly, had a part in this work. My especial thanks to Professor Victor Elconin for his criticism and continued interest in this dissertation are long overdue. Alf ANALYSIS OF JOHN DOS PASSOS' U.S.A. CHAPTER I THE CRITICS The 42nd Parallel, the first volume of the trilogy, U.S.A., was first published on February 19, 1930- It was followed by 1919 on March 10, 1932, and The Big Money on August 1, 1936. U.S.A., which combines these three novels, was issued on January 27, 1938. There is as yet no full-length critical and biographical study of Dos Passes, although one is now in the process of being edited for publication.^ His work has, however, attracted the notice of the leading reviewers and is discussed in those treatises dealing with the American novel of the twentieth cen tury. -

New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936

NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 NEW MASSES INDEX NEW MASSES INDEX 1936 By Theodore F. Watts Copyright 2007 ISBN 0-9610314-0-8 Phoenix Rising 601 Dale Drive Silver Spring, Maryland 20910-4215 Cover art: William Sanderson Regarding these indexes to New Masses: These indexes to New Masses were created by Theodore Watts, who is the owner of this intellectual property under US and International copyright law. Mr. Watts has given permission to the Riazanov Library and Marxists.org to freely distribute these three publications… New Masses Index 1926 - 1933 New Masses Index 1934 - 1935 New Masses Index 1936 … in a not for profit fashion. While it is my impression Mr. Watts wishes this material he created be as widely available as possible to scholars, researchers, and the workers movement in a not for profit fashion, I would urge others seeking to re-distribute this material to first obtain his consent. This would be mandatory, especially, if one wished to distribute this material in a for sale or for profit fashion. Martin H. Goodman Director, Riazanov Library digital archive projects January 2015 Patchen, Rebecca Pitts, Philip Rahv, Genevieve Taggart, Richard Wright, and Don West. The favorite artist during this two-year span was Russell T. Limbach with more than one a week for the run. Other artists included William Gropper, John Mackey, Phil Bard, Crockett Johnson, Gardner Rea, William Sanderson, A. Redfield, Louis Lozowick, and Adolph Dehn. Other names, familiar to modem readers, abound: Bernarda Bryson and Ben Shahn, Maxwell Bodenheim, Erskine Caldwell, Edward Dahlberg, Theodore Dreiser, Ilya Ehrenberg, Sergei Eisenstein, Hanns Eisler, James T. -

The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2001 The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction Walter Edwin Squire University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Squire, Walter Edwin, "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2001. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/6439 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Edwin Squire entitled "The aesthetic diversity of American proletarian fiction." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Mary E. Papke, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Walter Squire entitled "The Aesthetic Diversity of American Proletarian Fiction." I have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

Tamwag Fawf000053 Lo.Pdf

A LETTER FROM AMERICA By Pam Flett- WILL be interested in hearing what you think of Roosevelt’s foreign policy. When he made the speech at Chicago, I was startled and yet tremendously thrilled. It certainly looks as if something will have to be done to stop Hitler and Mussolini. But I wonder what is behind Roosevelt's speech. What does he plan to do? And when you get right down to it, what can we do? It’s easy to say “Keep out of War,” but how to keep out? TREAD in THE FIGHT that the ‘American League is coming out with a pamphlet by Harty F. Ward on this subject—Neutrality llready and an American sent in Peace my order. Policy. You I’ve know you can hardly believe anything the newspapers print these days_and I’m depending gare end ors on hare caer Phiets. For instance, David said, hational, when we that read i¢ The was Fascist_Inter- far-fetched and overdone. But the laugh’s for on him, everything if you can that laugh pamphlet at it- Fe dered nigiae th fact, the pamphiot is more up- iendalainow than Fodey'eipener eso YOUR NEXT YEAR IN ART BUT I have several of the American League pamphlets—Women, War and Fascism, Youth Demands WE'VE stolen a leaf from the almanac, which not only tells you what day it is but gives you Peace, A Blueprint for Fascism advice on the conduct of life. Not that our 1938 calendar carries instructions on planting-time (exposing the Industrial Mobiliza- tion Plan)—and I’m also getting But every month of it does carry an illustration that calls you to the struggle for Democracy and Why Fascism Leads to War and peace, that pictures your fellow fighters, and tha gives you a moment’s pleasure A Program Against War and Fascism. -

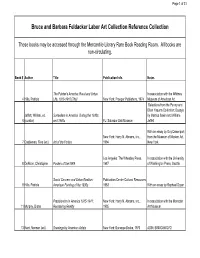

Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection

Page 1 of 31 Bruce and Barbara Feldacker Labor Art Collection Reference Collection These books may be accessed through the Mercantile Library Rare Book Reading Room. All books are non-circulating. Book # Author Title Publication Info. Notes The Painter's America: Rural and Urban In association with the Whitney 4 Hills, Patricia Life, 1810-1910 [The] New York: Praeger Publishers, 1974 Museum of American Art Selections from the Penny and Elton Yasuna Collection; Essays Jeffett, William, ed. Surrealism in America During the 1930s by Martica Sawin and William 6 (curator) and 1940s FL: Salvador Dali Museum Jeffett With an essay by Guy Davenport; New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., from the Museum of Modern Art, 7 Castleman, Riva (ed.) Art of the Forties 1994 New York Los Angeles: The Wheatley Press, In association with the University 8 DeNoon, Christopher Posters of the WPA 1987 of Washington Press, Seattle Social Concern and Urban Realism: Publication Center Cultural Resources, 9 Hills, Patricia American Painting of the 1930s 1983 With an essay by Raphael Soyer Precisionism in America 1915-1941: New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., In association with the Montclair 11 Murphy, Diana Reordering Reality 1995 Art Museum 13 Kent, Norman (ed.) Drawings by American Artists New York: Bonanza Books, 1970 ASIN: B000G5WO7Q Page 2 of 31 Slatkin, Charles E. and New York: Oxford University Press, 14 Shoolman, Regina Treasury of American Drawings 1947 ASIN: B0006AR778 15 American Art Today National Art Society, 1939 ASIN: B000KNGRSG Eyes on America: The United States as New York: The Studio Publications, Introduction and commentary on 16 Hall, W.S. -

The Masses Index 1911-1917

The Masses Index 1911-1917 1 Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series THE MASSES INDEX 1911-1917 1911-1917 By Theodore F. Watts \ Forthcoming volumes in the "Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series:" The Liberator (1918-1924) The New Masses (Monthly, 1926-1933) The New Masses (Weekly, 1934-1948) Foreword The handful ofyears leading up to America's entry into World War I was Socialism's glorious moment in America, its high-water mark ofenergy and promise. This pregnant moment in time was the result ofdecades of ferment, indeed more than 100 years of growing agitation to curb the excesses of American capitalism, beginning with Jefferson's warnings about the deleterious effects ofurbanized culture, and proceeding through the painful dislocation ofthe emerging industrial economy, the ex- cesses ofspeculation during the Civil War, the rise ofthe robber barons, the suppression oflabor unions, the exploitation of immigrant labor, through to the exposes ofthe muckrakers. By the decade ofthe ' teens, the evils ofcapitalism were widely acknowledged, even by champions ofthe system. Socialism became capitalism's logical alternative and the rallying point for the disenchanted. It was, of course, merely a vision, largely untested. But that is exactly why the socialist movement was so formidable. The artists and writers of the Masses didn't need to defend socialism when Rockefeller's henchmen were gunning down mine workers and their families in Ludlow, Colorado. Eventually, the American socialist movement would shatter on the rocks ofthe Russian revolution, when it was finally confronted with the reality ofa socialist state, but that story comes later, after the Masses was run from the stage. -

NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH and MAKING of the US ART CULTURE DURING the 1930’S

MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’s A Master’s Thesis By GÖZDE PINAR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2013 To My Parents…. MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’S Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by GÖZDE PINAR In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA September 2013 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Edward P. Kohn Thesis Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Kenneth Weisbrode Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in History. -------------------------- Asst. Prof. Dennis Bryson Examining Committee Member Approved by the Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences. -------------------------- Prof. Dr. Erdal Erel Director ABSTRACT MURALS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS: NELSON ROCKEFELLER-DIEGO RIVERA CLASH AND MAKING OF THE US ART CULTURE DURING THE 1930’S Pınar, Gözde M.A., Department of History, Bilkent University Supervisor: Assist. -

Sponsors of Writing and Workersâ•Ž Education in the 1930S

Community Literacy Journal Volume 11 Issue 1 Fall, Special Issue: Building Engaged Article 3 Infrastructure Fall 2016 Write. Persist. Struggle: Sponsors of Writing and Workers’ Education in the 1930s Deborah Mutnick Dr. Long Island University - Brooklyn Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/communityliteracy Recommended Citation Mutnick, Deborah. “Write. Persist. Struggle: Sponsors of Writing and Workers’ Education in the 1930s.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, 2016, pp. 10–21, doi:10.25148/clj.11.1.009245. This work is brought to you for free and open access by FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Literacy Journal by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. community literacy journal Write. Persist. Struggle: Sponsors of Writing and Workers’ Education in the 1930s Deborah Mutnick Organizations like the John Reed Clubs and the WPA Federal Writers’ Project, as well as publications like The New Masses can be seen as “literacy sponsors” of the U.S. literary left in the 1930s, particularly the young, the working class, and African American writers. The vibrant, inclusionary, activist, literary culture of that era reflected a surge of revolutionary ideas and activity that seized the imagination of a generation of writers and artists, including rhetoricians like Kenneth Burke. Here I argue that this history has relevance for contemporary community writing projects, which collectively lack the political cohesiveness and power of the national and international movements that sponsored the 1930s literary left but may anticipate another global period of struggle for democracy in which writers and artists can play a significant role.