Downloaded-ND from 4.0 Brill.Com09/23/2021 License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Penguins and Polar Bears Shapero Rare Books 93

OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS Shapero Rare Books 93 OF PENGUINS AND POLAR BEARS EXPLORATION AT THE ENDS OF THE EARTH 32 Saint George Street London W1S 2EA +44 20 7493 0876 [email protected] shapero.com CONTENTS Antarctica 03 The Arctic 43 2 Shapero Rare Books ANTARCTIca Shapero Rare Books 3 1. AMUNDSEN, ROALD. The South Pole. An account of “Amundsen’s legendary dash to the Pole, which he reached the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912. before Scott’s ill-fated expedition by over a month. His John Murray, London, 1912. success over Scott was due to his highly disciplined dogsled teams, more accomplished skiers, a shorter distance to the A CORNERSTONE OF ANTARCTIC EXPLORATION; THE ACCOUNT OF THE Pole, better clothing and equipment, well planned supply FIRST EXPEDITION TO REACH THE SOUTH POLE. depots on the way, fortunate weather, and a modicum of luck”(Books on Ice). A handsomely produced book containing ten full-page photographic images not found in the Norwegian original, First English edition. 2 volumes, 8vo., xxxv, [i], 392; x, 449pp., 3 folding maps, folding plan, 138 photographic illustrations on 103 plates, original maroon and all full-page images being reproduced to a higher cloth gilt, vignettes to upper covers, top edges gilt, others uncut, usual fading standard. to spine flags, an excellent fresh example. Taurus 71; Rosove 9.A1; Books on Ice 7.1. £3,750 [ref: 96754] 4 Shapero Rare Books 2. [BELGIAN ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION]. Grande 3. BELLINGSHAUSEN, FABIAN G. VON. The Voyage of Fete Venitienne au Parc de 6 a 11 heurs du soir en faveur de Captain Bellingshausen to the Antarctic Seas 1819-1821. -

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

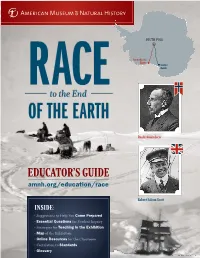

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This Collection Was the Gift of Howard J

Howard J. Garber Letter Collection This collection was the gift of Howard J. Garber to Case Western Reserve University from 1979 to 1993. Dr. Howard Garber, who donated the materials in the Howard J. Garber Manuscript Collection, is a former Clevelander and alumnus of Case Western Reserve University. Between 1979 and 1993, Dr. Garber donated over 2,000 autograph letters, documents and books to the Department of Special Collections. Dr. Garber's interest in history, particularly British royalty led to his affinity for collecting manuscripts. The collection focuses primarily on political, historical and literary figures in Great Britain and includes signatures of all the Prime Ministers and First Lords of the Treasury. Many interesting items can be found in the collection, including letters from Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Robert Browning Thomas Hardy, Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, King George III, and Virginia Woolf. Descriptions of the Garber Collection books containing autographs and tipped-in letters can be found in the online catalog. Box 1 [oversize location noted in description] Abbott, Charles (1762-1832) English Jurist. • ALS, 1 p., n.d., n.p., to ? A'Beckett, Gilbert A. (1811-1856) Comic Writer. • ALS, 3p., April 7, 1848, Mount Temple, to Morris Barnett. Abercrombie, Lascelles. (1881-1938) Poet and Literary Critic. • A.L.S., 1 p., March 5, n.y., Sheffield, to M----? & Hughes. Aberdeen, George Hamilton Gordon (1784-1860) British Prime Minister. • ALS, 1 p., June 8, 1827, n.p., to Augustous John Fischer. • ANS, 1 p., August 9, 1839, n.p., to Mr. Wright. • ALS, 1 p., January 10, 1853, London, to Cosmos Innes. -

Hot Rocks from Cold Places: a Field, Geochemical and Geochronological Study from the High Arctic Large Igneous P Rovince (HALIP) at Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut

! !"#$%"&'($)*"+$,"-.$/-0&1(2$3$451-.6$71"&81+5&0-$09.$ 71"&8*"9"-":5&0-$;#<.=$)*"+$#81$!5:8$3*&$>0*:1$ ?:91"<($/*"@59&1$A!3>?/B$0#$3C1-$!15D1*:$?(-09.6$ E<90@<#$ $ $ by Cole Girard Kingsbury A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Earth Sciences Ottawa – Carleton Geoscience Centre and Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2016 Cole Girard Kingsbury ! ! !"#$%&'$() ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) The geology of the Arctic is greatly influenced by a period of widespread Cretaceous magmatic activity, the High Arctic Large Igneous Province (HALIP). Two major tholeiitic magmatic pulses characterize HALIP: an initial 120 -130 Ma pulse that affected Arctic Canada and formally adjacent regions of Svalbard (Norway) and Franz Josef Land (Russia). In Canada, this pulse fed lava flows of the Isachsen Formation. A second 90-100 Ma pulse that apparently only affected the Canadian side of the Arctic, fed flood basalts of the Strand Fiord Formation. The goal of this thesis is to improve understanding of Arctic magmatism of the enigmatic HALIP through field, remote sensing, geochemical and geochronology investigations of mafic intrusive rocks collected in the South Fiord area of Axel Heiberg Island, Nunavut, and comparison with mafic lavas of the Isachsen and Strand Fiord Formations collected from other localities on the Island. Ground-based and remote sensing observations of the South Fiord area reveal a complex network of mafic sills and mainly SSE-trending dykes. Two new U-Pb baddeleyite ages of 95.18 ± 0.35 Ma and 95.56 ± 0.24 Ma from South Fiord intrusions along with geochemical similarity confirm these intrusions (including the SSE-trending dykes) are feeders for the Strand Fiord Formation lavas. -

A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2014 A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939 Smith, Gordon W. University of Calgary Press "A historical and legal study of sovereignty in the Canadian north : terrestrial sovereignty, 1870–1939", Gordon W. Smith; edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2014 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/50251 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca A HISTORICAL AND LEGAL STUDY OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE CANADIAN NORTH: TERRESTRIAL SOVEREIGNTY, 1870–1939 By Gordon W. Smith, Edited by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ISBN 978-1-55238-774-0 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at ucpress@ ucalgary.ca Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specificwork without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Peary Arctic Club Expedition to the North Pole, 1908-9 Author(S): Robert E

Peary Arctic Club Expedition to the North Pole, 1908-9 Author(s): Robert E. Peary and R. A. Harris Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Aug., 1910), pp. 129-144 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1777691 Accessed: 08-05-2016 16:09 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 143.89.105.150 on Sun, 08 May 2016 16:09:32 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Geographical Journal. No. 2. AUGUST, 1910. VOL. XXXVI. PEARY ARCTIC CLUB EXPEDITION TO THE NORTH POLE, 1908-9.* By COMMANDER ROBERT E. PEARY. THE last North Polar Expedition of the Peary Arctic Club t left New York harbour on July 6, 1908, in the steamer Roosevelt, built by the club especially for Arctic work, and commanded by Captain Robert A. Bartlett. The members of the expedition were as follows, a total of 22: Commander R. E. Peary, U.S.N., Commander of the expedition; Captain R. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Paper Number: 2897 a History of Early Antarctic Fossil Discoveries in Support of the Supercontinent Gondwana Clary, R.M.1, and Sharpe, T.2

Paper Number: 2897 A History of Early Antarctic Fossil Discoveries in Support of the Supercontinent Gondwana Clary, R.M.1, and Sharpe, T.2 1Mississippi State University, Box 5448, Mississippi State, MS 39762 USA; [email protected] 2Centre for Lifelong Learning, Cardiff University, UK ___________________________________________________________________________ First proposed by Eduard Suess (1831-1914), the supercontinent Gondwana included the present-day continents of South America, Africa, Australia, India, and Antarctica. Alexander Du Toit (1878-1948) expanded Suess’ work in his 1937 book, Our Wandering Continents; An Hypothesis of Continental Drifting. Correlating evidence to support the inclusion of Antarctica in the Gondwana supercontinent would result from the stratigraphic and paleontological data collected within early polar expeditions. Early rock and fossil specimens of Antarctica were recovered by the 1829-1831 Antarctic Expedition sponsored by the United States of America. The expedition included a scientific program, supported by the Lyceum for Natural History of the City of New York. James Eights (1798-1882) produced quality scientific work, including a geological description of the Shetland Islands, and the first fossil of the Antarctic—carbonized wood [1, 2]. The Norwegian expedition of 1893-1894, under Carl Anton Larsen (1860-1924), also found petrified wood fossils on Seymour Island. The wood hinted of a warmer climate in Antarctica’s past, and sparked scientific interest [3]. Within the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1897-1922), additional fossils were uncovered. Cretaceous ammonites, molluscs, echinoderms and leaves were collected on Seymour Island, and additional plant fossils at Hope Bay, by geologist Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjöld (1869-1928) during the Swedish South Polar Expedition of 1901-1904. -

The “Coolest” and Northernmost FAQ Welcome to UNIS We Hope You Will

The “coolest” and northernmost FAQ Everything you might or might not want to know about your stay at UNIS Made by the UNIS Student Council autumn 2016 Welcome to UNIS We hope you will have a great time here ͺ Before arrival Important: Remember to apply for housing, and sign your contract before arriving, and check the dates. Your room will first be opened in the afternoon the day your contract starts, so if you arrive 3am you should make sure the contract starts the day before arrival. If your contract starts in the weekend your room will be opened at Friday afternoon (Samskipnaden opens your room and leaves the key inside, so you don’t need to worry about not being able to access your room) Rifles: If you want to borrow rifles (you need them when leaving town) during your stay please read the rifle part http://www.unis.no/studies/student-life/new-students/ Q: What do I need to pack? http://www.unis.no/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/PACKING-LIST.pdf - When it comes to equipment and how warm clothing you need it is up to what you plan to do and how easily you freeze - You should bring or buy a pair of thin liner gloves to wear under thicker mittens. During field work you will find that it is very hard to write with the thick scooter mittens, and that is awfully cold to do anything bare handed in -20 degrees celsius - Liner gloves can be very nice to have during the safety course, you will do part of it outside.