Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

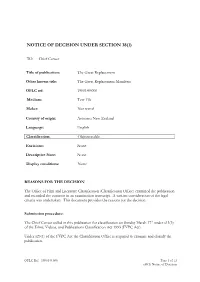

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

More About the Album Thank Yous • About the Guitars

Produced by AM & Dustin DeLage Recording, engineering and mixing by Dustin DeLage at Cabin Studios, Leesburg VA Additional remote recording by Ken Lubinsky at lack Hills Studios, Plain"eld CT Atlantic $cean wa&es recorded by Mic'elle McKnig't at East eac', Charlestown R)* Mastering by ill +ol,, +ol, Productions, Alexandria VA* -ra.'ic Design by Stilson -reene, Leesburg VA ack co&er .'oto by Christi Porter P'otogra.'y, Lincoln VA All songs written by AM and ©Catalooch Music, BMI, except "Margaret" by Andrew McKnight ©19 !, "uccess Music, and "#ur Meeting Is #ver" %traditional&' #'e Songs #'e and 1. Embarking 1:12 ,M - vo<a-s7 a<ousti< & e-e<tri< guitars7 s-i"e guitar7 2. Margaret/Treasures in My Chest 4:56 &ative Ameri<an fute 3. Web of Mystery 3:24 9a<he- Tay-or - ce--o 4. eft Behin" 3:55 Mi<hae- Rohrer ; e-e<tri< an" u:right bass 5. #assage/(Fathers No') Our Meeting is Over 2:1+ isa Tay-or - drums7 harmony vo<a-s 6. ,retas Cu-ver 4:13 >ef Arey - man"o-in .. , Dram to the Ho-i"ays 5:13 4te:hanie Thom:son7 Tony Denikos - harmony vo<a-s 1. The Gift 3:51 3. 4ons & Fathers 3:53 $t'er Essential Musical Pieces 1+. My Litt-e To'n 3:35 ,-y M<@night - piano (Margaret( 11. ong Ago an" Far A'ay 1:5+ Warren M<@night - piano an" organ $4ons & Fathers( 12. Entre-azan"o 0:43 Ma"e-eine M<@night - f""-e (Long Ago & Far A'ay(7 13. -

Here We Are at 500! the BRL’S 500 to Be Exact and What a Trip It Has Been

el Fans, here we are at 500! The BRL’s 500 to be exact and what a trip it has been. Imagibash 15 was a huge success and the action got so intense that your old pal the Teamster had to get involved. The exclusive coverage of that ppv is in this very issue so I won’t spoil it and give away the ending like how the ship sinks in Titanic. The Johnny B. Cup is down to just four and here are the representatives from each of the IWAR’s promotions; • BRL Final: Sir Gunther Kinderwacht (last year’s winner) • CWL Final: Jane the Vixen Red (BRL, winner of 2017 Unknown Wrestler League) • IWL Final: Nasty Norman Krasner • NWL Final: Ricky Kyle In one semi-final, we will see bitter rivals Kinderwacht and Red face off while in the other the red-hot Ricky Kyle will face the, well, Nasty Normal Krasner. One of these four will win The self-professed “Greatest Tag team wrestler the 4th Johnny B Cup and the results will determine the breakdown of the prizes. ? in the world” debuted in the NWL in 2012 and taunt-filled promos earned him many enemies. The 26th Marano Memorial is also down to the final 5… FIVE? Well since the Suburban Hell His “Teamster Challenge” offered a prize to any Savages: Agent 26 & Punk Rock Mike and Badd Co: Rick Challenger & Rick Riley went to a NWL rookie who could capture a Tag Team title draw, we will have a rematch. The winner will advance to face Sledge and Hammer who won with him, but turned ugly when he kept blaming the CWL bracket. -

Indecent by PAULA VOGEL Directed by WENDY C

McGuire Proscenium Stage / Feb 17 – Mar 24, 2018 Indecent by PAULA VOGEL directed by WENDY C. GOLDBERG PLAY GUIDE Inside THE PLAY Synopsis • 3 Characters and Setting • 4 Inspiration for Indecent • 5 Responses to Indecent • 6 Responses to The God of Vengeance • 7 THE PLAYWRIGHT On Paula Vogel • 8 Paula Vogel on Indecent • 9 Paula Vogel on Sholem Asch • 10-11 Glossary: Concepts, Words, Ideas • 12-15 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION For Further Reading and Understanding • 16 Play guides are made possible by Guthrie Theater Play Guide Copyright 2018 DRAMATURG Jo Holcomb GRAPHIC DESIGNER Akemi Graves CONTRIBUTORS Jo Holcomb Guthrie Theater, 818 South 2nd Street, Minneapolis, MN 55415 All rights reserved. With the exception of classroom use by teachers and individual personal use, no part of this Play Guide ADMINISTRATION 612.225.6000 may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic BOX OFFICE 612.377.2224 or 1.877.44.STAGE TOLL-FREE or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in guthrietheater.org • Joseph Haj, artistic director writing from the publishers. Some materials published herein are written especially for our Guide. Others are reprinted by permission of their publishers. The Guthrie Theater receives support from the National The Guthrie creates transformative theater experiences that ignite the imagination, stir Endowment for the Arts. This activity is made possible in part by the Minnesota State Arts Board, through an appropriation the heart, open the mind, and build community through the illumination of our common by the Minnesota State Legislature. The Minnesota State Arts Board received additional funds to support this activity from humanity. -

The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. The Radical Roots of the Alt-Right Josh Vandiver Ball State University Various source media, Political Extremism and Radicalism in the Twentieth Century EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The radical political movement known as the Alt-Right Revolution, and Evolian Traditionalism – for an is, without question, a twenty-first century American audience. phenomenon.1 As the hipster-esque ‘alt’ prefix 3. A refined and intensified gender politics, a suggests, the movement aspires to offer a youthful form of ‘ultra-masculinism.’ alternative to conservatism or the Establishment Right, a clean break and a fresh start for the new century and .2 the Millennial and ‘Z’ generations While the first has long been a feature of American political life (albeit a highly marginal one), and the second has been paralleled elsewhere on the Unlike earlier radical right movements, the Alt-Right transnational right, together the three make for an operates natively within the political medium of late unusual fusion. modernity – cyberspace – because it emerged within that medium and has been continuously shaped by its ongoing development. This operational innovation will Seminal Alt-Right figures, such as Andrew Anglin,4 continue to have far-reaching and unpredictable Richard Spencer,5 and Greg Johnson,6 have been active effects, but researchers should take care to precisely for less than a decade. While none has continuously delineate the Alt-Right’s broader uniqueness. designated the movement as ‘Alt-Right’ (including Investigating the Alt-Right’s incipient ideology – the Spencer, who coined the term), each has consistently ferment of political discourses, images, and ideas with returned to it as demarcating the ideological territory which it seeks to define itself – one finds numerous they share. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

Australia Muslim Advocacy Network

1. The Australian Muslim Advocacy Network (AMAN) welcomes the opportunity to input to the UN Special Rapporteur on the Freedom of Religion or Belief as he prepares this report on the Impact of Islamophobia/anti-Muslim hatred and discrimination on the right to freedom of thought, conscience religion or belief. 2. We also welcome the opportunity to participate in your Asia-Pacific Consultation and hear from the experiences of a variety of other Muslims organisations. 3. AMAN is a national body that works through law, policy, research and media, to secure the physical and psychological welfare of Australian Muslims. 4. Our objective to create conditions for the safe exercise of our faith and preservation of faith- based identity, both of which are under persistent pressure from vilification, discrimination and disinformation. 5. We are engaged in policy development across hate crime & vilification laws, online safety, disinformation and democracy. Through using a combination of media, law, research, and direct engagement with decision making parties such as government and digital platforms, we are in a constant process of generating and testing constructive proposals. We also test existing civil and criminal laws to push back against the mainstreaming of hate, and examine whether those laws are fit for purpose. Most recently, we are finalising significant research into how anti-Muslim dehumanising discourse operates on Facebook and Twitter, and the assessment framework that could be used to competently and consistently assess hate actors. A. Definitions What is your working definition of anti-Muslim hatred and/or Islamophobia? What are the advantages and potential pitfalls of such definitions? 6. -

Printed Covers Sailing Through the Air As Their Tables Are REVIEWS and REFUTATIONS Ipped

42 RECOMMENDED READING Articles Apoliteic music: Neo-Folk, Martial Industrial and metapolitical fascism by An- ton Shekhovtsov Former ELF/Green Scare Prisoner Exile Now a Fascist by NYC Antifa Books n ٻThe Nature of Fascism by Roger Gri Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler by Roger n ٻGri n ٻFascism edited by Roger Gri Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism, and the Politics of Identity by Nicholas Go- A FIELD GUIDE TO STRAW MEN odrick-Clarke Gods of the Blood: The Pagan Revival and White Separatism by Mattias Gardell Modernity and the Holocaust by Zygmunt Bauman Sadie and Exile, Esoteric Fascism, and Exterminate All the Brutes by Sven Lindqvist Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement by Don Hamerquist, Olympias Little White Lies J. Sakai, Anti-Racist Action Chicago, and Mark Salotte Baedan: A Journal of Queer Nihilism Baedan 2: A Queer Journal of Heresy Baedan 3: A Journal of Queer Time Travel Against His-story, Against Leviathan! by Fredy Perlman Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture by Arthur Evans The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revo- lutionary Atlantic by Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker Gone to Croatan: Origins of North American Dropout Culture edited by Ron Sakolsky and James Koehnline The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life by Georgy Katsia cas 1312 committee // February 2016 How the Irish Became White by Noel Ignatiev How Deep is Deep Ecology? by George Bradford Against the Megamachine: Essays on Empire and Its Enemies by David Watson Elements of Refusal by John Zerzan Against Civilization edited by John Zerzan This World We Must Leave and Other Essays by Jacques Camatte 41 total resistance mounted to the advent of industrial society. -

Hate by Infected

Infected by Hate: Far-Right Attempts to Leverage Anti-Vaccine Sentiment Dr. Liram Koblentz-Stenzler, Alexander Pack March 2021 Synopsis The purpose of this article is to alert and educate on a new phenomenon that first appeared worldwide in November 2020, as countries started developing COVID-19 vaccination plans. Far-fight extremists, white supremacists in particular, identified pre-existing concerns in the general public regarding the potential vaccines’ effectiveness, safety, and purpose. In an effort to leverage these concerns, the far-right actors have engaged in a targeted campaign to introduce and amplify disinformation about the potential COVID-19 vaccines via online platforms. These campaigns have utilized five main themes. First, content increasing chaos and promoting accelerationism. Second, content to improve recruitment and radicalization. Third, content connecting COVID-19 or the proposed vaccines to pre-existing conspiracies in the movement. Fourth, content fostering anti-minority sentiment. Fifth, they have begun producing content advocating individual- initiative (lone wolf) attacks against COVID-19 manufacturers. Authorities must be cognizant of this phenomenon and think of ways to prevent it. Failure to recognize and appropriately respond may result in increased recruitment and mobilization within the far-right movement. Similarly, failure to curtail this type of rhetoric will likely increase the public’s hesitancy to go and be vaccinated, increasing the difficulty of eradicating COVID-19. Additionally, far-right extremists are likely to continue suggesting that COVID-19 vaccines are part of a larger conspiracy in order to persuade potential supporters to engage in individual-initiative (lone wolf) attacks. As a result, COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers and distribution venues are likely to be potential targets. -

The Culture of Wikipedia

Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia Good Faith Collaboration The Culture of Wikipedia Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. Foreword by Lawrence Lessig The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Web edition, Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Michael Reagle Jr. CC-NC-SA 3.0 Purchase at Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble | IndieBound | MIT Press Wikipedia's style of collaborative production has been lauded, lambasted, and satirized. Despite unease over its implications for the character (and quality) of knowledge, Wikipedia has brought us closer than ever to a realization of the centuries-old Author Bio & Research Blog pursuit of a universal encyclopedia. Good Faith Collaboration: The Culture of Wikipedia is a rich ethnographic portrayal of Wikipedia's historical roots, collaborative culture, and much debated legacy. Foreword Preface to the Web Edition Praise for Good Faith Collaboration Preface Extended Table of Contents "Reagle offers a compelling case that Wikipedia's most fascinating and unprecedented aspect isn't the encyclopedia itself — rather, it's the collaborative culture that underpins it: brawling, self-reflexive, funny, serious, and full-tilt committed to the 1. Nazis and Norms project, even if it means setting aside personal differences. Reagle's position as a scholar and a member of the community 2. The Pursuit of the Universal makes him uniquely situated to describe this culture." —Cory Doctorow , Boing Boing Encyclopedia "Reagle provides ample data regarding the everyday practices and cultural norms of the community which collaborates to 3. Good Faith Collaboration produce Wikipedia. His rich research and nuanced appreciation of the complexities of cultural digital media research are 4. The Puzzle of Openness well presented. -

Al-QAEDA and the ARYAN NATIONS

Al-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCAULDIAN PERSPECTIVE by HUNTER ROSS DELL Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN CRIMINOLOGY AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON DECEMBER 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For my parents, Charles and Virginia Dell, without whose patience and loving support, I would not be who or where I am today. November 10, 2006 ii ABSTRACT AL-QAEDA AND THE ARYAN NATIONS A FOUCALTIAN PERSPECTIVE Publication No. ______ Hunter Ross Dell, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2006 Supervising Professor: Alejandro del Carmen Using Foucauldian qualitative research methods, this study will compare al- Qaeda and the Aryan Nations for similarities while attempting to uncover new insights from preexisting information. Little or no research had been conducted comparing these two organizations. The underlying theory is that these two organizations share similar rhetoric, enemies and goals and that these similarities will have implications in the fields of politics, law enforcement, education, research and United States national security. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................... ii ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................... -

FUNDING HATE How White Supremacists Raise Their Money

How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money 1 RESPONDING TO HATE FUNDING HATE INTRODUCTION 1 SELF-FUNDING 2 ORGANIZATIONAL FUNDING 3 CRIMINAL ACTIVITY 9 THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK: CROWDFUNDING 10 BITCOIN AND CRYPTOCURRENCIES 11 THE FUTURE OF WHITE SUPREMACIST FUNDING 14 2 RESPONDING TO HATE How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money It’s one of the most frequent questions the Anti-Defamation League gets asked: WHERE DO WHITE SUPREMACISTS GET THEIR MONEY? Implicit in this question is the assumption that white supremacists raise a substantial amount of money, an assumption fueled by rumors and speculation about white supremacist groups being funded by sources such as the Russian government, conservative foundations, or secretive wealthy backers. The reality is less sensational but still important. As American political and social movements go, the white supremacist movement is particularly poorly funded. Small in numbers and containing many adherents of little means, the white supremacist movement has a weak base for raising money compared to many other causes. Moreover, ostracized because of its extreme and hateful ideology, not to mention its connections to violence, the white supremacist movement does not have easy access to many common methods of raising and transmitting money. This lack of access to funds and funds transfers limits what white supremacists can do and achieve. However, the means by which the white supremacist movement does raise money are important to understand. Moreover, recent developments, particularly in crowdfunding, may have provided the white supremacist movement with more fundraising opportunities than it has seen in some time. This raises the disturbing possibility that some white supremacists may become better funded in the future than they have been in the past.