ONLINE APPENDIX Highway to Hitler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya* May 10, 2014 How far can the media protect or undermine democratic institutions in unconsolidated democracies, and how persuasive can they be in ensuring public support for dictator’s policies? We study this question in the context of Germany between 1929 and 1939. Radio slowed down the growth of political support for the Nazis, when Weimar government introduced pro-government political news in 1929, denying access to the radio for the Nazis up till January 1933. This effect was reversed in 5 weeks after the transfer of control over the radio to the Nazis following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. After full consolidation of power, radio propaganda helped the Nazis to enroll new party members and encouraged denunciations of Jews and other open expressions of anti-Semitism. The effect of Nazi radio propaganda varied depending on the listeners’ predispositions toward the message. Nazi radio was most effective in places where anti-Semitism was historically high and had a negative effect on the support for Nazi messages in places with historically low anti-Semitism. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! * Maja Adena is from Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Ruben Enikolopov is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School, Moscow. Maria Petrova is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School. Veronica Santarosa is from the Law School of the University of Michigan. Ekaterina Zhuravskaya is from Paris School of Economics (EHESS) and the New Economic School. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

J'une 28, 1933. on This 28Th Day Or June 1933~ the Board· Ot TI

J'une 28, 1933. On this 28th day or June 1933~ the Board· ot TI'U8tees ot the ArkansE State Teachers College met in the President's otti ce at Conway, Arkansas at 11 a.m• with the tbllowing members present and voting: Hirst, Leonard; Humphreys, Compere~ A.ndrews, Fre,uenthe.l ,!Uld: Smith Minutes or the l ast meeting were r ead and approved. Motion by Andrews, seocaded by Smith (l) that Miss Jessie Montgomer be employed as s Upe rvisor tor 1218 jun1 or h igb school in the Training School tor t~ months or July and August at a salaey or $114.90 a month; (2) that Kiss Waldron be assigned in t h9 epi:ropriation budget as auistant int~ DepartmEll.t or Social SoiE11.ce 111.th no change in salary; .(3) that Jerry Dalrymple, Athletic Coach, b.e assigned as adcUtiona.l assistant instead ot an assistant in Social Seienoe, at a salary of ~200.00 a month beginning September l; (4) that the salaries ot Miss Lucy Torson and Miss Edith Langley be made il950 each tor the next year in order to contorm to t he approprta t:l.on bulget; (5) that the resolution passed April 15, 1933 asking the Governor to readjust the amounts appropriated tor salaries in Ite~ 29 and 30 tor 1933-34 be rescinded Motion carrt ed • .llotion by Andrews~ seconded by HumJi>,reys that Guy E. Smith, Disbursing Age~, be instructed to pay tor the grading or oorrespondence papers at the rate ot t l.50 tor each term hours credit; that said payment be paid frcm the Extension Fund upon the eompletion ot each correspondence course; tb:i.t the pa}'JD3nt for tuch work made to meui>ers of tbe regular tacuUy be in addition to salaries tor t.each1ng~ provided that no member or the faculty will be paid more than $450.00 par annum in addi tio:n to the regutar salary. -

Presentation Slides

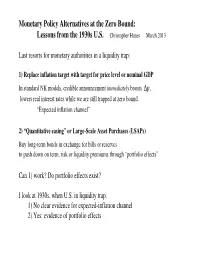

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi Party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M

Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofré-Vilà, Christopher M. Meissner, Martin McKee, and David Stuckler NBER Working Paper No. 24106 December 2017, Revised in September 2020 JEL No. E6,N1,N14,N44 ABSTRACT We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. Voting data from a thousand districts and a hundred cities for four elections between 1930 and 1933 shows that areas more affected by austerity (spending cuts and tax increases) had relatively higher vote shares for the Nazi party. We also find that the localities with relatively high austerity experienced relatively high suffering (measured by mortality rates) and these areas’ electorates were more likely to vote for the Nazi party. Our findings are robust to a range of specifications including an instrumental variable strategy and a border-pair policy discontinuity design. Gregori Galofré-Vilà Martin McKee Department of Sociology Department of Health Services Research University of Oxford and Policy Manor Road Building London School of Hygiene Oxford OX1 3UQ & Tropical Medicine United Kingdom 15-17 Tavistock Place [email protected] London WC1H 9SH United Kingdom Christopher M. Meissner [email protected] Department of Economics University of California, Davis David Stuckler One Shields Avenue Università Bocconi Davis, CA 95616 Carlo F. Dondena Centre for Research on and NBER Social Dynamics and Public Policy (Dondena) [email protected] Milan, Italy [email protected] Austerity and the Rise of the Nazi party Gregori Galofr´e-Vil`a Christopher M. Meissner Martin McKee David Stuckler Abstract: We study the link between fiscal austerity and Nazi electoral success. -

The Political Economy of Argentina's Abandonment

Going through the labyrinth: the political economy of Argentina’s abandonment of the gold standard (1929-1933) Pablo Gerchunoff and José Luis Machinea ABSTRACT This article is the short but crucial history of four years of transition in a monetary and exchange-rate regime that culminated in 1933 with the final abandonment of the gold standard in Argentina. That process involved decisions made at critical junctures at which the government authorities had little time to deliberate and against which they had no analytical arsenal, no technical certainties and few political convictions. The objective of this study is to analyse those “decisions” at seven milestone moments, from the external shock of 1929 to the submission to Congress of a bill for the creation of the central bank and a currency control regime characterized by multiple exchange rates. The new regime that this reordering of the Argentine economy implied would remain in place, in one form or another, for at least a quarter of a century. KEYWORDS Monetary policy, gold standard, economic history, Argentina JEL CLASSIFICATION E42, F4, N1 AUTHORS Pablo Gerchunoff is a professor at the Department of History, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] José Luis Machinea is a professor at the Department of Economics, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] 104 CEPAL REVIEW 117 • DECEMBER 2015 I Introduction This is not a comprehensive history of the 1930s —of and, if they are, they might well be convinced that the economic policy regarding State functions and the entrance is the exit: in other words, that the way out is production apparatus— or of the resulting structural to return to the gold standard. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

The London Monetary and Economic Conference of 1933 and the End of the Great Depression: a “Change of Regime” Analysis

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THE LONDON MONETARY AND ECONOMIC CONFERENCE OF 1933 AND THE END OF THE GREAT DEPRESSION: A “CHANGE OF REGIME” ANALYSIS Sebastian Edwards Working Paper 23204 http://www.nber.org/papers/w23204 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 2017 I thank Michael Poyker for his assistance. I thank Michael Bordo, Josh Hausman, and George Tavlas for comments. I have benefitted from conversations with Ed Leamer. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2017 by Sebastian Edwards. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. The London Monetary and Economic Conference of 1933 and the End of The Great Depression: A “Change of Regime” Analysis Sebastian Edwards NBER Working Paper No. 23204 February 2017 JEL No. B21,B22,B26,E3,E31,E42,F31,N22 ABSTRACT In this paper I analyze the London Monetary and Economic Conference of 1933, an almost forgotten episode in U.S. monetary history. I study how the Conference shaped dollar policy during the second half of 1933 and early 1934. I use daily data to investigate the way in which the Conference and related policies associated to the gold standard affected commodity prices, bond prices, and the stock market. -

Federal Reserve Bulletin June 1935

FEDERAL RESERVE BULLETIN JUNE 1935 ISSUED BY THE FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD AT WASHINGTON Business and Credit Conditions Industrial Advances by Federal Reserve Banks Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1935 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FEDERAL RESERVE BOARD Ex-officio members: MARRINER S. ECCLES, Governor. HENRY MORGENTHAU, Jr., J. J. THOMAS, Vice Governor. Secretary of the Treasury, Chairman, CHARLES S. HAMLIN. J. F. T. O'CONNOR, ADOLPH C. MILLER. Comptroller of the Currency. GEORGE R. JAMES. M. S. SZYMCZAK. LAWRENCE CLAYTON, Assistant to the Governor. LAUCHLIN CURRIE, Assistant Director, Division of ELLIOTT L. THURSTON, Special Assistant to the Governor. Research and Statistics. CHESTER MORRILL, Secretary. WOODLIEF THOMAS, Assistant Director, Division of J. C. NOELL, Assistant Secretary. Research and Statistics. LISTON P. BETHEA, Assistant Secretary. E. L. SMEAD, Chief, Division of Bank Operations. S. R. CARPENTER, Assistant Secretary. J. R. VAN FOSSEN, Assistant Chief, Division of Bank WALTER WYATT, General Counsel. Operations. GEORGE B. VEST, Assistant General Counsel. J. E. HORBETT, Assistant Chief, Division of Bank B. MAGRUDER WINGFIELD, Assistant General Counsel. Operations. LEO H. PAULGER, Chief, Division of Examinations. CARL E. PARRY, Chief, Division of Security Loans. R. F. LEONARD, Assistant Chief, Division of Examina- PHILIP E. BRADLEY, Assistant Chief, Division of Security tions. Loans. C. E. CAGLE, Assistant Chief, Division of Examinations. O. E. FOULK, Fiscal Agent. FRANK J. DRINNEN, Federal Reserve Examiner. JOSEPHINE E. LALLY, Deputy Fiscal Agent. E. A. GOLDENWEISER, Director, Division of Research and Statistics. FEDERAL ADVISORY COUNCIL District no. -

The Great Depression: an Overview by David C

Introduction The Great Depression: An Overview by David C. Wheelock Why should students learn about the Great Depression? Our grandparents and great-grandparents lived through these tough times, but you may think that you should focus on more recent episodes in Ameri- can life. In this essay, I hope to convince you that the Great Depression is worthy of your interest and deserves attention in economics, social studies and history courses. One reason to study the Great Depression is that it was by far the worst economic catastrophe of the 20th century and, perhaps, the worst in our nation’s history. Between 1929 and 1933, the quantity of goods and services produced in the United States fell by one-third, the unemployment rate soared to 25 percent of the labor force, the stock market lost 80 percent of its value and some 7,000 banks failed. At the store, the price of chicken fell from 38 cents a pound to 12 cents, the price of eggs dropped from 50 cents a dozen to just over 13 cents, and the price of gasoline fell from 10 cents a gallon to less than a nickel. Still, many families went hungry, and few could afford to own a car. Another reason to study the Great Depression is that the sheer magnitude of the economic collapse— and the fact that it involved every aspect of our economy and every region of our country—makes this event a great vehicle for teaching important economic concepts. You can learn about inflation and defla- tion, Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and unemployment by comparing the Depression with more recent experiences. -

Nber Working Paper Series

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HIGHWAY TO HITLER Nico Voigtlaender Hans-Joachim Voth Working Paper 20150 http://www.nber.org/papers/w20150 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 May 2014 For helpful comments, we thank Sascha Becker, Tim Besley, Leonardo Bursztyn, Davide Cantoni, Bruno Caprettini, Melissa Dell, Ruben Enikolopov, Rick Hornbeck, Gerard Padró i Miquel, Torsten Persson, Diego Puga, Giacomo Ponzetto, Jim Snyder, David Strömberg, and Noam Yuchtman. Seminar audiences at Basel University, Bonn University, CREI, King’s College London, the Juan March Institute, LSE, Warwick, Yale, Zurich, and at the Barcelona Summer Forum offered useful suggestions. We are grateful to Hans-Christian Boy, Vicky Fouka, Cathrin Mohr, Casey Petroff, Colin Spear and Inken Töwe for outstanding research assistance. Ruben Enikolopov kindly shared data on radio signal strength in Nazi Germany. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2014 by Nico Voigtlaender and Hans-Joachim Voth. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Highway to Hitler Nico Voigtlaender and Hans-Joachim Voth NBER Working Paper No. 20150 May 2014, Revised April 2016 JEL No. H54,N44,N94,P16 ABSTRACT When does infrastructure investment win “hearts and minds”? We analyze a famous case – the building of the highway network in Nazi Germany. -

Distribution and Seasonal Movements of the House Sparrow

Bird-Banding 2o] NICHOLS,Distribution of theHouse Sparrow January DISTRIBUTION AND SEASONAL MOVEMENTS OF THE HOUSE SPARROW By Joun T. N•cuoLs Fi•oM January, 1930, to October, 1933, 450 House Sparrows were banded at Garden City, New York. Adult House Sparrowsare notoriouslytrap-shy, seldomrepeating or return- ing. Such scattering repeats and returns as there have been to date do not, in themselves,prove much as to the local move- ments of the species. However, adults were banded on the right leg, and recog- nizably young birds on the left leg, thus dividing the popula- tion into six groupseasily recognizableat the trapping station by sight. The varying proportionsof these groupspresent by observationare shownin percentagesin Table 1. We will begin by summarizing the most obvious and best groundedconclusions based on this table: (1) Young birds as a class leave the trapping station im- mediately if they are strong on the wing and independent of their parents. Their leaving seemsto be due to lack of place memory, correlated with a general lack of memory which causesthem to repeat much more freely than the adults. It is not that they are crowded out by the adults or seek a differ- ent environment,for at the sametime the proportionof birds of the year at the station rises, as would be expectedat that season. It is rather a matter of chance,with a drifting popula- tion, chancewhich will later bring a small proportion of them back to the station again. (2) The proportion of banded adult males at the trapping station has risen rapidly since 1930 with continued banding, and is subjectto wide seasonalfluctuations, which can only be explained by a more or less regular return of birds from out- side to the station.