The Police Mission in the Twenty-First Century: Rebalancing the Role of the First Public Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Policing 97

THE HISTORY 4 OF POLICING distribute or post, copy, not Do Copyright ©2015 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. “The myth of the unchanging police “You never can tell what a man is able dominates much of our thinking about to do, but even though I recommend the American police. In both popular ten, and nine of them may disappoint discourse and academic scholarship one me and fail, the tenth one may surprise continually encounters references to the me. That percentage is good enough for ‘tradition-bound’ police who are resistant me, because it is in developing people to change. Nothing could be further from that we make real progress in our own the truth. The history of the American society.” police over the past one hundred years is —August Vollmer (n.d.) a story of drastic, if not radical change.” —Samuel Walker (1977) distribute INTRODUCTION: POLICING LEARNING OBJECTIVES or After finishing this chapter, you should be able to: AS A DYNAMIC ENTITY Policing as we know it today is relatively new. 4.1 Summarize the influence of early The notion of a professional uniformed police officer English policing on policing and the receiving specialized training on the law, weapon use, increasing professionalization of policing and self-defense is taken for granted. In fact, polic- in the United States over time. post,ing has evolved from a system in which officers ini- tially were appointed by friends, given no training, 4.2 Identify how the nature of policing in the provided power to arrest without warrants, engaged United States has changed over time. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 812 Tuesday No. 5 18 May 2021 PARLIAMENTARYDEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDEROFBUSINESS Questions Right-to-Work Checks for UK Nationals...............................................................................................................431 Electricity Supplies from Europe ............................................................................................................................433 Railway Industry Association Report .....................................................................................................................436 Size of the House of Lords ....................................................................................................................................440 Osimertinib Cancer Treatment Private Notice Question...........................................................................................................................................443 Skills and Post-16 Education Bill [HL] First Reading ...........................................................................................................................................................447 Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Steps and Local Authority Enforcement Powers) (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2021 Motion to Approve...................................................................................................................................................448 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (Cash Searches: Code of Practice) Order 2021 Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 -

Assessing the Value of Mounted Police Units in the UK

Making and Breaking Barriers Assessing the value of mounted police units in the UK Chris Giacomantonio, Ben Bradford, Matthew Davies and Richard Martin For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/rr830 While the use of mounted police (i.e. police horses and riders) can be traced back to before the advent of the modern police service in 1829, very little is known about the actual work of mounted police from either academic or practitioner standpoints. Police horses are thought to have unique operational and symbolic value, particularly in public order policing (making barriers) and community engagement (breaking barriers) Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif., and Cambridge, UK deployments. They may represent a calming presence or, and potentially at the same time, an imposing threat of force. Yet, the relationship between the use of police horses and broader notions of policing by consent in the UK is presently unknown, and all R® is a registered trademark. evidence for these claims is anecdotal at best. In recent years, mounted units have come under resource scrutiny in the UK due to austerity measures. Some forces have eliminated their mounted capacities altogether, while others have developed collaborative or mutual assistance arrangements with © Copyright 2015 RAND Corporation and University of Oxford neighbouring forces. The relative costs and benefits of the available options – maintaining units, merging and centralising mounted resources or eliminating them in whole or part – cannot at present be assessed confidently by individual forces or by national coordinating agencies such as the Home Office, the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) and the National Police Coordination Centre (NPoCC). -

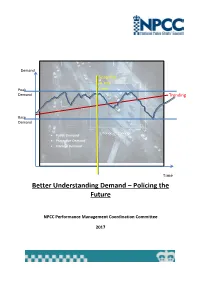

Better Understanding Demand – Policing the Future

Demand Snapshot at any Peak time Demand Trending Base Demand Public Demand Protective Demand Internal Demand Time Better Understanding Demand – Policing the Future NPCC Performance Management Coordination Committee 2017 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Foreword by Chief Constable Steve Finnigan CBE QPM ......................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Summary of Findings............................................................................................................................... 9 Summary of Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 11 The Demand Reference Group ............................................................................................................. 14 Chapter 1: Demand in Context and Whole System Thinking ............................................................... 16 Chapter 2: Towards a Common Understanding ................................................................................... 19 Chapter 3: Legitimacy of Demand and Public Expectation .................................................................. -

Canterbury Christ Church University's Repository of Research Outputs Http

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Heaton, R. and Tong, S. (2017) ‘Set in stone?’. Police Professional. Link to official URL (if available): https://www.policeprofessional.com/news/set-in-stone-2/ This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Police Professional Article ‘Set in Stone?’ Introduction Peel’s Principles are widely seen as the foundation of much successful policing in Western societies. They are believed to confer legitimacy on a service which exercises coercive powers such as arrest and detention on citizens, on behalf of the state. Legitimacy is important for many reasons, perhaps the most obvious and practical one being the relatively small number of officers in relation to the wider population. In the UK, Home Office figures suggest that there is approximately one police officer per 500 citizens, or more realistically one officer on duty per 2500 citizens. It follows that the service relies heavily upon self-policing by the vast majority of the population, most of the time. Where police intervention is necessary, legitimacy is also the key to the wider judicial system which relies upon the willingness of people to work with the police as witnesses. In a fast-changing and sceptical world, Peel’s Principles are still used to a remarkable extent, as a touchstone against which the quality of policing is judged. -

Evolving Value and Purpose of Policing ‘Inward’ to Address Internal Management Issues11

POLICING FOR A SAFER WORLD Singapore 2012 ................................................................................................................... ABOUT THIS BOOK Pearls in Policing 2012 POLICING FOR A SAFER WORLD It is widely recognised by top level law enforcement executives that it is necessary to actively engage in international cooperation to develop effective strategies to best position law enforcement in the future. The need for commissioners and chief executive officers from around the world to jointly identify risks, threats and opportunities as well as research new ideas and realities for policing led to the launch of the Pearls in Policing initiative in 2007. The only global think-tank within policing of its kind. Under the responsibility of the Pearls Curatorium, the Dutch based Pearls in Policing Secretariat had sole charge of the organisation of the Pearls conferences in 2007, 2008 and 2009. In 2010, the Australian Federal Police hosted the fourth Pearls in Policing conference in Sydney. The fifth conference in 2011 was again hosted in the Netherlands and the 2012 conference took place in Singapore co-hosted by the Singapore Police Force (SPF) and the Pearls Curatorium. This publication is a record of the events and discussions that took place at the Singapore conference ‘Policing for a Safer World’. March 2013 ................................................................................................................... 5 CONTENT CONFERENCE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 FOREWORD - by Mr. Peter Ng, Commissioner of the Singapore Police Force 17 PEARLS SINGAPORE Nine Emerging Issues 21 NEW REALITIES Policing in an Age of Austerity 31 NEW IDEAS The True Value of Policing (Academic Essay) 53 NEW THREATS Are We Prepared for A Cyber 9-11? 85 NEW OPPORTUNITIES The Police as a Learning Frontline Organisation 99 The Use of Social Media by Law Enforcement PEARLS INTERVIEWED The Challenges of Making the World Safer 119 REFLECTIONS - by Mr. -

Create.Canterbury.Ac.Uk

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. Lydon, D. (2018) Police legitimacy and the policing of protest: identifying contextual influences associated with the construction and shaping of protester perceptions of police legitimacy and attitudes to compliance and cooperation beyond the limits of procedural justice and elaborated social identity approaches. Ph.D. thesis, Canterbury Christ Church University. Contact: [email protected] Police legitimacy and the policing of protest: Identifying contextual influences associated with the construction and shaping of protester perceptions of police legitimacy and attitudes to compliance and cooperation beyond the limits of procedural justice and elaborated social identity approaches. by David Lydon Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2018 1 Abstract Police legitimacy is fundamental to the relationship between the state, citizens and their police, and this is nowhere more challenging than in public order policing contexts. Procedural Justice (PJ) and the Elaborated Social Identity Model (ESIM) have gained dominance in UK policing as the means of establishing greater perceptions of police legitimacy and public compliance and cooperation with the police and the law. -

Yemen's Fight Against AQAP

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2017 Is Community Based Policing the Answer? Yemen’s Fight against AQAP Maximilian Kaehler Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2017.POL.ST.03 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Kaehler, Maximilian, "Is Community Based Policing the Answer? Yemen’s Fight against AQAP" (2017). Senior Theses. 73. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2017.POL.ST.03 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is Community Based Policing the Answer? Yemen’s Fight against AQAP By Maximilian Kaehler Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In Political Science Department of Political Science & International Studies Dominican University of California 17 April 2017 Abstract Throughout history we have seen drastic changes in methods for combating terrorism; however, as a society we have never been able to find an effective solution. In recent years we have seen countries use community based policing in an effort to fight terrorism at home; how would adopting community based policing efforts help or hurt countries throughout the Middle East in combating terrorism? I believe that implementing community based policing into these countries would drastically improve civilian and government relationships as well as hinder terrorists’ ability to recruit new member from these areas. I conduct a multi-case study then apply those models to the country of Yemen to simulate how the policies would affect the ability to combat Al- Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula. -

A Comparative Study of Public Order Policing In

Same Destination, Different Journey: A Comparative Study of Public Order Policing in Britain and Spain. Derek Emilio Barham Professional Doctorate in Policing, Security and Community Safety Awarded by London Metropolitan University This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of ProfD 2016 Abstract Public order policing is about power and control. The preservation and maintenance of order is a defining characteristic of the sovereign power. It is a highly political activity which is also emotive, controversial and reflects national culture and identity. Public order policing asks serious questions of the police and represents the most contentious policing activity in modern democratic states. The purpose of this study is to increase and improve current knowledge of public order policing by comparing the policing of disorder in Britain and Spain. It reviews two high profile incidents, the 2011 London Riots and the 2014 “22M” Protests in Madrid, using a fusion of Waddington’s “Flashpoints Model” and Herbert’s “Normative Orders” to comparatively analyse the incidents. The study is supported by a comprehensive literature review and interviews with experienced police public order commanders. This thesis concludes that British public order policing is in need of considerable reform to improve operational effectiveness, efficiency and professionalism. It identifies several key themes which contributed to the inability of the Metropolitan Police to respond effectively to the serious disorder and criminality which proliferated across 22 of London’s 32 boroughs in August 2011. These include the need to review British public order tactics, invest in the training of specialist public order units and improve the understanding of crowd psychology. -

Policing in the UK: a Brief Guide

Policing in the UK: A Brief Guide 1 What do the Police do? How do we police? Neighbourhood policing and the Peelian Principles are the heart and soul of the British model. This is the aspect of policing that most people relate to and evidence points to increases in public confidence directly linked to visibility of police officers and staff. Public confidence underpins police legitimacy and has practical benefits. These include gaining intelligence about criminal activity within communities, opportunities for engaging with neighbourhood groups and boosting recruitment of those either wishing to volunteer or join through the Special Constabulary. Peelian Principles 1. The basic mission for which the police exist is to prevent crime and disorder. 2. The ability of the police to perform their duties is dependent upon public approval of police actions. 3. Police must secure the willing co-operation of the public in voluntary observance of the law to be able to secure and maintain the respect of the public. 4. The degree of co-operation of the public that can be secured diminishes proportionately to the necessity of the use of physical force. 5. Police seek and preserve public favour not by catering to public opinion but by constantly demonstrating absolute impartial service to the law. 6. Police use physical force to the extent necessary to secure observance of the law or to restore order only when the exercise of persuasion, advice and warning is found to be insufficient. 7. Police, at all times, should maintain a relationship with the public that gives reality to the historic tradition that the police are the public and the public are the police; the police being only members of the public who are paid to give full-time attention to duties which are incumbent on every citizen in the interests of community welfare and existence. -

(2016) Policing by Consent: Some Practitioner Perceptions. Doctoral Thesis, University of Sunderland

Robertson, Adam (2016) Policing by Consent: Some Practitioner Perceptions. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/6991/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Policing by Consent: Some Practitioner Perceptions Adam Bertram Robertson A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Faculty for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Education and Science August 2014 Authors Declaration The Researcher hereby signs himself the ‘writer’ of this thesis. Signature……………………………………………………………. Date…………………………………………………………………. Copyright Copyright of this thesis cannot be authorised. Abstract The purpose of this work is to examine the concept or notion of policing by consent and it is important to note, at the outset, that the vast majority of the literature produced on the subject, both current and past, has concentrated on policing by consent from many different viewpoints with one quite startling omission. There does not appear to be any academic study based on the views and perceptions of it [consent] that the practitioners, the police themselves, have. In order to correct this imbalance the study therefore set out, by means of a series of semi-structured interviews, to obtain the views and perceptions of both serving and retired officers of a principle, certainly of policing in England and Wales, which is at the very core of their professional lives. Prior to the interviews, which took place between November 2007 and December 2008, the officers were arranged into four cohorts, each cohort consisting of ten officers, and within each cohort, the officers range across the continuum of rank, ethnicity, gender and length of service. -

Watch Groups, Surveillance and Doing It for Themselves

This is a repository copy of Watch groups, surveillance and doing it for themselves. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/138670/ Version: Published Version Article: Spiller, K. and L'Hoiry, X.D. orcid.org/0000-0001-9138-7666 (2019) Watch groups, surveillance and doing it for themselves. Surveillance and Society, 17 (3/4). pp. 288-304. ISSN 1477-7487 10.24908/ss.v17i3/4.8637 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ ! Watch Groups, Surveillance, and Doing It for Article Themselves Keith Spiller Xavier L’Hoiry ! ! ! Birmingham City University, UK University of Sheffield, UK [email protected] [email protected] Abstract! This paper focuses on surveillant relations between citizens and police. We consider how online platforms enable the public to support the task of policing, as well as empowering the public to work without and beyond the police. While community-supported policing interventions are not new, more recently mobile and accessible technologies have promoted and enabled a DIY (Do-It- Yourself) culture towards policing amongst the public.