In the Blink of Closed Eyes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

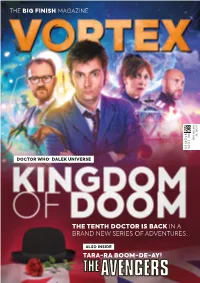

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

Doctor Who 50 Jaar Door Tijd En Ruimte

Doctor Who 50 jaar door tijd en ruimte 1963-1989 2005-nu 1963-1989 2005-nu Doctor Who • Britse science fiction Sydney Newman, Verity Lambert, Warris Hussein Doctor Who • Britse science fiction • Moeilijke start • Showrunners • Genre • Studio • Karakter Doctor • 23 november 1963 Doctor Who • Britse science fiction • Show bijna afgevoerd • Educatief kinderprogramma • Tijdreizen = • Toekomst: wetenschap • Verleden: geschiedenis Doctor Who • Britse science fiction • Show bijna afgevoerd • Educatief kinderprogramma • Vier hoofdpersonages • Ian Chesterton • Barbara Wright • Susan Foreman • The Doctor ? Doctor WHO? The Oncoming Storm The Doctor (1963-1966) • Alien • ‚Time Lord’ van planeet Gallifrey • Reist door tijd en ruimte in TARDIS • Vast op aarde met kleindochter William Hartnell - Eerste Doctor Ian, Barbara en Susan TARDIS • ‚Chameleon Circuit’ • Time And Relative Dimension In Space • Eigen zwaartekracht-veld Daleks • Creativiteit op een beperkt budget • Eerste aliens in de show • Planeet Skaro • Aartsvijand Doctor • Culturele invloed • Iconisch uiterlijk Cybermen • Laatste verhaal William Hartnell • Emotieloos • Mens in Cyberman veranderen • ‚Upgrades’ • The Borg Regeneratie Tweede Doctor (1966-1969) • Regeneraties • Van ‚strenge grootvader’ naar ‚kosmische vagebond’ • Twee harten • Sonic screwdriver Patrick Troughton - Tweede Doctor Sonic Screwdriver • Opent sloten, scant omgeving • Kan alles (behalve hout) • Kan te veel? De Time Lords Tweede Doctor (1966-1969) • Regeneraties • Van ‚strenge grootvader’ naar ‚kosmische vagebond’ • Twee harten -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This One, with Gratitude, Is for DON CONGDON

FAHRENHEIT 451 by Ray Bradbury This one, with gratitude, is for DON CONGDON. FAHRENHEIT 451: The temperature at which book-paper catches fire and burns PART I: THE HEARTH AND THE SALAMANDER IT WAS A PLEASURE TO BURN. IT was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see things blackened and changed. With the brass nozzle in his fists, with this great python spitting its venomous kerosene upon the world, the blood pounded in his head, and his hands were the hands of some amazing conductor playing all the symphonies of blazing and burning to bring down the tatters and charcoal ruins of history. With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black. He strode in a swarm of fireflies. He wanted above all, like the old joke, to shove a marshmallow on a stick in the furnace, while the flapping pigeon- winged books died on the porch and lawn of the house. While the books went up in sparkling whirls and blew away on a wind turned dark with burning. Montag grinned the fierce grin of all men singed and driven back by flame. He knew that when he returned to the firehouse, he might wink at himself, a minstrel man, Does% burntcorked, in the mirror. Later, going to sleep, he would feel the fiery smile still gripped by his Montag% face muscles, in the dark. -

Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M

April 17 - 23, 2009 SPANISH FORK CABLE GUIDE 9 Friday Prime Time, April 17 4 P.M. 4:30 5 P.M. 5:30 6 P.M. 6:30 7 P.M. 7:30 8 P.M. 8:30 9 P.M. 9:30 10 P.M. 10:30 11 P.M. 11:30 BASIC CABLE Oprah Winfrey Å 4 News (N) Å CBS Evening News (N) Å Entertainment Ghost Whisperer “Save Our Flashpoint “First in Line” ’ NUMB3RS “Jack of All Trades” News (N) Å (10:35) Late Show With David Late Late Show KUTV 2 News-Couric Tonight Souls” ’ Å 4 Å 4 ’ Å 4 Letterman (N) ’ 4 KJZZ 3The People’s Court (N) 4 The Insider 4 Frasier ’ 4 Friends ’ 4 Friends 5 Fortune Jeopardy! 3 Dr. Phil ’ Å 4 News (N) Å Scrubs ’ 5 Scrubs ’ 5 Entertain The Insider 4 The Ellen DeGeneres Show (N) News (N) World News- News (N) Two and a Half Wife Swap “Burroughs/Padovan- Supernanny “DeMello Family” 20/20 ’ Å 4 News (N) (10:35) Night- Access Holly- (11:36) Extra KTVX 4’ Å 3 Gibson Men 5 Hickman” (N) ’ 4 (N) ’ Å line (N) 3 wood (N) 4 (N) Å 4 News (N) Å News (N) Å News (N) Å NBC Nightly News (N) Å News (N) Å Howie Do It Howie Do It Dateline NBC A police of cer looks into the disappearance of a News (N) Å (10:35) The Tonight Show With Late Night- KSL 5 News (N) 3 (N) ’ Å (N) ’ Å Michigan woman. (N) ’ Å Jay Leno ’ Å 5 Jimmy Fallon TBS 6Raymond Friends ’ 5 Seinfeld ’ 4 Seinfeld ’ 4 Family Guy 5 Family Guy 5 ‘Happy Gilmore’ (PG-13, ’96) ›› Adam Sandler. -

Blink by Steven Moffat EXT

Blink by Steven Moffat EXT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE - NIGHT Big forbidding gates. Wrought iron, the works. A big modern padlock on. Through the gates, an old house. Ancient, crumbling, overgrown. Once beautiful - still beautiful in decay. Panning along: on the gates - DANGER, KEEP OUT, UNSAFE STRUCTURE -- The gates are shaking, like someone is climbing them -- -- and then a figure drops into a view on the other side. Straightens up into a close-up. SALLY SPARROW. Early twenties, very pretty, just a bit mad, just a bit dangerous. She's staring at the house, eyes shining. Big naughty grin. SALLY Sexy! And she starts marching up the long gravel drive ... CUT TO: INT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE. HALLWAY - NIGHT The big grand house in darkness, huge sweeping staircase, shuttered window, debris everywhere -- One set of shutters buckles from an impact from the inside, splinters. SALLY SPARROW, kicking her away in -- CUT TO: INT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE. HALLWAY/ROOMS - NIGHT SALLY, clutching a camera. Walks from one room to another. Takes a photograph. Her face: fascinated, loving this creepy old place. Takes another photograph. CUT TO: INT. WESTER DRUMLINS HOUSE. CONSERVATORY ROOM - NIGHT In the conservatory now - the windows looking out on a darkened garden. And a patch of rotting wallpaper catches SALLY'S eye -- 2. High on the wall, just below the picture rail, a corner of wallpaper is peeling away, drooping mournfully down from the wall -- -- revealing writing on the plaster behind. Just two letters we can see - BE - the beginning of a word -- She reaches up on tiptoes and pulls at the hanging frond of wallpaper. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Gaslightpdffinal.Pdf

Credits. Book Layout and Design: Miah Jeffra Cover Artwork: Pseudodocumentation: Broken Glass by David DiMichele, Courtesy of Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco ISBN: 978-0-692-33821-6 The Writers Retreat for Emerging LGBTQ Voices is made possible, in part, by a generous contribution by Amazon.com Gaslight Vol. 1 No. 1 2014 Gaslight is published once yearly in Los Angeles, California Gaslight is exclusively a publication of recipients of the Lambda Literary Foundation's Emerging Voices Fellowship. All correspondence may be addressed to 5482 Wilshire Boulevard #1595 Los Angeles, CA 90036 Details at www.lambdaliterary.org. Contents Director's Note . 9 Editor's Note . 11 Lisa Galloway / Epitaph ..................................13 / Hives ....................................16 Jane Blunschi / Snapdragon ................................18 Miah Jeffra / Coffee Spilled ................................31 Victor Vazquez / Keiki ....................................35 Christina Quintana / A Slip of Moon ........................36 Morgan M Page / Cruelty .................................51 Wayne Johns / Where Your Children Are ......................53 Wo Chan / Our Majesties at Michael's Craft Shop ..............66 / [and I, thirty thousand feet in the air, pop] ...........67 / Sonnet by Lamplight ............................68 Yana Calou / Mortars ....................................69 Hope Thompson/ Sharp in the Dark .........................74 Yuska Lutfi Tuanakotta / Mother and Son Go Shopping ..........82 Megan McHugh / I Don't Need to Talk -

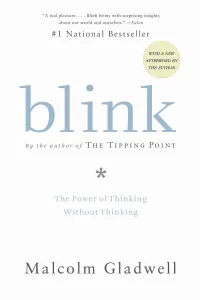

Blink: the Power of Thinking Without Thinking

PENGUIN BOOKS BLINK Author, journalist, cultural commentator and intellectual adventurer, Malcolm Gladwell was born in 1963 in England to a Jamaican mother and an English mathematician father. He grew up in Canada and graduated with a degree in history from the University of Toronto in 1984. From 1987 to 1996, he was a reporter for the Washington Post, first as a science writer and then as New York City bureau chief. Since 1996, he has been a staff writer for the New Yorker magazine. His curiosity and breadth of interests are shown in New Yorker articles ranging over a wide array of subjects including early childhood development and the flu, not to mention hair dye, shopping and what it takes to be cool. His phenomenal bestseller The Tipping Point captured the world’s attention with its theory that a curiously small change can have unforeseen effects, and the phrase has become part of our language, used by writers, politicians and business people everywhere to describe cultural trends and strange phenomena. BLINK The Power of Thinking Without Thinking MALCOLM GLADWELL PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, -

A Dpics-Ii Analysis of Parent-Child Interactions

WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this dissertation is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This dissertation does not include proprietary or classified information. _______________________ Lori Jean Klinger Certificate of Approval: ________________________ ________________________ Steven K. Shapiro Elizabeth V. Brestan, Chair Associate Professor Associate Professor Psychology Psychology ________________________ ________________________ James F. McCoy Elaina M. Frieda Associate Professor Assistant Professor Psychology Experimental Psychology _________________________ Joe F. Pittman Interim Dean Graduate School WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Lori Jean Klinger A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 15, 2006 WHAT ARE YOUR CHILDREN WATCHING? A DPICS-II ANALYSIS OF PARENT-CHILD INTERACTIONS IN TELEVISION CARTOONS Lori Jean Klinger Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this dissertation at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. ________________________ Signature of Author ________________________ Date of Graduation iii VITA Lori Jean Klinger, daughter of Chester Klinger and JoAnn (Fetterolf) Bachrach, was born October 24, 1965, in Ashland, Pennsylvania. She graduated from Owen J. Roberts High School as Valedictorian in 1984. She graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1988 and served as a Military Police Officer in the United States Army until 1992. -

Edition 2019

YEAR-END EDITION 2019 Global Headquarters Republic Records 1755 Broadway, New York City 10019 © 2019 Mediabase 1 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 6TH STRAIGHT YEAR UMG SCORES TOP 3 -- AS INTERSCOPE, CAPITOL CLAIM #2 AND #3 SPOTS For the sixth consecutive year, REPUBLIC is the #1 label for Mediabase chart share. • The 2019 chart year is based on the time period from November 11, 2018 through November 9, 2019. • All spins are tallied for the full 52 weeks and then converted into percentages for the chart share. • The final chart share includes all applicable label split-credit as submitted to Mediabase during the year. • For artists, if a song had split-credit, each artist featured was given the same percentage for the artist category that was assigned to the label share. REPUBLIC’S total chart share was 19.2% -- up from 16.3% last year. Their Top 40 chart share of 28.0% was a notable gain over the 22.1% they had in 2018. REPUBLIC took the #1 spot at Rhythmic with 20.8%. They were also the leader at Hot AC; where a fourth quarter surge landed them at #1 with 20.0%, that was up from a second place 14.0% finish in 2018. Other highlights for REPUBLIC in 2019: • The label’s total spin counts for the year across all formats came in at 8.38 million, an increase of 20.2% over 2018. • This marks the label’s second highest spin total in its history. • REPUBLIC had several artist accomplishments, scoring three of the top four at Top 40 with Ariana Grande (#1), Post Malone (#2), and the Jonas Brothers (#4). -

Olson Medical Clinic Services Que Locura Noticiero Univ

TVetc_35 9/2/09 1:46 PM Page 6 SATURDAY ** PRIME TIME ** SEPTEMBER 5 TUESDAY ** AFTERNOON ** SEPTEMBER 8 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 12 PM 12:30 1 PM 1:30 2 PM 2:30 3 PM 3:30 4 PM 4:30 5 PM 5:30 <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> <BROADCAST<STATIONS<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> The Lawrence Welk Show ‘‘When Guy Lombardo As Time Goes Keeping Up May to Last of the The Red Green Soundstage ‘‘Billy Idol’’ Rocker Austin City Limits ‘‘Foo Fighters’’ Globe Trekker Classic furniture in KUSD d V (11:30) Sesame Barney & Friends The Berenstain Between the Lions Wishbone ‘‘Mixed Dragon Tales (S) Arthur (S) (EI) WordGirl ‘‘Mr. Big; The Electric Fetch! With Ruff Cyberchase Nightly Business KUSD d V the Carnival Comes’’; ‘‘Baby and His Royal By Appearances December Summer Wine Show ‘‘Comrade Billy Idol performs his hits to a Grammy Award-winning group Foo Hong Kong; tribal handicrafts of the Street (S) (EI) (N) (S) (EI) Bears (S) (S) (EI) Breeds’’ (S) (EI) Book Ends’’ (S) (EI) Company (S) (EI) Ruffman (S) (EI) ‘‘Codename: Icky’’ Report (N) (S) Elephant Walk’’; ‘‘Tiger Rag.’’ Canadians (S) Harold’’ (S) packed house. (S) Fighters perform. (S) Makonde tribes. (S) KTIV f X News (N) (S) Days of our Lives (N) (S) Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The Faith Little House on the Prairie ‘‘The King Is Extra (N) (S) The Ellen DeGeneres Show (Season News (N) (S) NBC Nightly News News (N) (S) The Insider (N) Law & Order: Criminal Intent A Law & Order A firefighter and his Law & Order: Special Victims News (N) (S) Saturday Night Live Anne Hathaway; the Killers.