White-Throated Cacholote Pseudoseisura Gutturalis And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity and Structure of Bird and Mammal Communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: Response to Agricultural Practices and Landscape Alterations

Diversity and structure of bird and mammal communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: response to agricultural practices and landscape alterations Julieta Decarre March 2015 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Division of Ecology and Evolution, Department of Life Sciences Imperial College London 2 Imperial College London Department of Life Sciences Diversity and structure of bird and mammal communities in the Semiarid Chaco Region: response to agricultural practices and landscape alterations Supervised by Dr. Chris Carbone Dr. Cristina Banks-Leite Dr. Marcus Rowcliffe Imperial College London Institute of Zoology Zoological Society of London 3 Declaration of Originality I herewith certify that the work presented in this thesis is my own and all else is referenced appropriately. I have used the first-person plural in recognition of my supervisors’ contribution. People who provided less formal advice are named in the acknowledgments. Julieta Decarre 4 Copyright Declaration The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work 5 “ …and we wandered for about four hours across the dense forest…Along the path I could see several footprints of wild animals, peccaries, giant anteaters, lions, and the footprint of a tiger, that is the first one I saw.” - Emilio Budin, 19061 I dedicate this thesis To my mother and my father to Virginia, Juan Martin and Alejandro, for being there through space and time 1 Book: “Viajes de Emilio Budin: La Expedición al Chaco, 1906-1907”. -

21 Sep 2018 Lists of Victims and Hosts of the Parasitic

version: 21 Sep 2018 Lists of victims and hosts of the parasitic cowbirds (Molothrus). Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum Brood parasitism is an awkward term to describe an interaction between two species in which, as in predator-prey relationships, one species gains at the expense of the other. Brood parasites "prey" upon parental care. Victimized species usually have reduced breeding success, partly because of the additional cost of caring for alien eggs and young, and partly because of the behavior of brood parasites (both adults and young) which may directly and adversely affect the survival of the victim's own eggs or young. About 1% of all bird species, among 7 families, are brood parasites. The 5 species of brood parasitic “cowbirds” are currently all treated as members of the genus Molothrus. Host selection is an active process. Not all species co-occurring with brood parasites are equally likely to be selected nor are they of equal quality as hosts. Rather, to varying degrees, brood parasites are specialized for certain categories of hosts. Brood parasites may rely on a single host species to rear their young or may distribute their eggs among many species, seemingly without regard to any characteristics of potential hosts. Lists of species are not the best means to describe interactions between a brood parasitic species and its hosts. Such lists do not necessarily reflect the taxonomy used by the brood parasites themselves nor do they accurately reflect the complex interactions within bird communities (see Ortega 1998: 183-184). Host lists do, however, offer some insight into the process of host selection and do emphasize the wide variety of features than can impact on host selection. -

Foraging Behavior of Plain-Mantled Tit-Spinetail (Leptasthenura Aegithaloides) in Semiarid Matorral, North-Central Chile

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 22: 247–256, 2011 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society FORAGING BEHAVIOR OF PLAIN-MANTLED TIT-SPINETAIL (LEPTASTHENURA AEGITHALOIDES) IN SEMIARID MATORRAL, NORTH-CENTRAL CHILE Andrew Engilis Jr. & Douglas A. Kelt Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Conservation Biology - University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Resumen. – Comportamiento de forrajeo del tijeral (Leptasthenura aegithaloides) en matorral semiárido, centro-norte de Chile. – Hemos estudiado el comportamiento de forrajeo del tijeral (Leptas- thenura aegithaloides) en el matorral del centro-norte de Chile. Se trata de una especie de la familia Fur- nariidae que es insectívora recolectora desde perchas. Frecuenta los arbustos más dominantes y busca presas y alimentos principalmente en el follaje, grupos de flores, pequeñas ramas y masas de líquenes. Los arbustos preferidos incluyen a Porlieria y Baccharis. Se alimentan desde alturas cercanas al suelo hasta arbustos superiores a dos metros de altura. Se los encuentra más frecuentemente en parejas o en grupos pequeños, posiblemente familias, de tres a cinco aves. Las densidades promedio en el matorral (1,49 - 1,69 aves por hectárea) son mayores que las reportadas para otros lugares. Los tijerales en el matorral forman grupos de especies mixtas con facilidad, especialmente en el invierno Austral. Su estrategia de forrajeo y su comportamiento son similares a las del Mito sastrecillo de América del Norte (Psaltriparus minimus) y del Mito común (Aegithalos caudatus), ambos de la familia Aegithalidae, sugir- iendo estrategias ecológicas convergentes en ambientes estructuralmente similares. Abstract. – We studied foraging behavior of Plain-mantled Tit-spinetail (Leptasthenura aegithaloides) in matorral (scrubland) habitat of north-central Chile. -

Bolivia: Endemic Macaws & More!

BOLIVIA: ENDEMIC MACAWS & MORE! PART II: FOOTHILLS, CLOUDFORESTS & THE ALTIPLANO SEPTEMBER 28–OCTOBER 8, 2018 Male Versicolored Barbet – Photo Andrew Whittaker LEADERS: ANDREW WHITTAKER & JULIAN VIDOZ LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM Bolivia continued to exceed expectations on Part 2 of our tour! Steadily climbing up into the mighty ceiling of South America that is the Andes, we enjoyed exploring many more new, different, and exciting unspoiled bird-rich habitats, including magical Yungas cloudforest stretching as far as the eye could see; dry and humid Puna; towering snow-capped Andean peaks; vast stretches of Altiplano with its magical brackish lakes filled with immense numbers of glimmering flamingoes, and one of my favorite spots, the magnificent and famous Lake Titicaca (with its own flightless grebe). An overdose of stunning Andean scenery combined with marvelous shows of flowering plants enhanced our explorations of a never-ending array of different and exciting microhabitats for so many special and interesting Andean birds. We were rewarded with a fabulous trip record total of 341 bird species! Combining our two exciting Bolivia tours (Parts 1 and 2) gave us an all-time VENT record, an incredible grand total of 656 different bird species and 15 mammals! A wondrous mirage of glimmering pink hues of all three species of flamingos on the picturesque Bolivian Altiplano – Photo Andrew Whittaker Stunning Andes of Bolivia near Soroto on a clear day of our 2016 trip – Photo Andrew Whittaker Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Bolivia Part 2, 2018 We began this second part of our Bolivian bird bonanza in the bustling city of Cochabamba, spending a fantastic afternoon birding the city’s rich lakeside in lovely late afternoon sun. -

Satellite Imagery Reveals New Critical Habitat for Endangered Bird Species in the High Andes of Peru

Vol. 13: 145–157, 2011 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published online February 16 doi: 10.3354/esr00323 Endang Species Res OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Satellite imagery reveals new critical habitat for Endangered bird species in the high Andes of Peru Phred M. Benham1, Elizabeth J. Beckman1, Shane G. DuBay1, L. Mónica Flores2, Andrew B. Johnson1, Michael J. Lelevier1, C. Jonathan Schmitt1, Natalie A. Wright1, Christopher C. Witt1,* 1Museum of Southwestern Biology and Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87110, USA 2Centro de Ornitologia y Biodiversidad (CORBIDI), Urb. Huertos de San Antonio, Surco, Lima, Peru ABSTRACT: High-resolution satellite imagery that is freely available on Google Earth provides a powerful tool for quantifying habitats that are small in extent and difficult to detect by medium- resolution Landsat imagery. Relictual Polylepis forests of the high Andes are of critical importance to several globally threatened bird species, but, despite growing international attention to Polylepis conservation, many gaps remain in our knowledge of its distribution. We examined high-resolution satellite imagery in Google Earth to search for new areas of Polylepis in south-central Peru that potentially support Polylepis-specialist bird species. In central Apurímac an extensive region of high- resolution satellite imagery contained 127 Polylepis fragments, totaling 683.15 ha of forest ranging from 4000 to 4750 m a.s.l. Subsequent fieldwork confirmed the presence of mature Polylepis forest and all 6 Polylepis-specialist bird species, 5 of which are considered globally threatened. Our find- ings (1) demonstrate the utility of Google Earth for applied conservation and (2) suggest improved prospects for the persistence of the Polylepis-associated avifauna. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Zootaxa, Pseudasthenes, a New Genus of Ovenbird (Aves

Zootaxa 2416: 61–68 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Pseudasthenes, a new genus of ovenbird (Aves: Passeriformes: Furnariidae) ELIZABETH DERRYBERRY,1 SANTIAGO CLARAMUNT,1 KELLY E. O’QUIN,1,2 ALEXANDRE ALEIXO,3 R. TERRY CHESSER,4 J. V. REMSEN JR.1 & ROBB T. BRUMFIELD1 1Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803 2Behavior Ecology Evolution Systematics Program, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 3Coordenação de Zoologia, Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Caixa Postal 399, CEP 66040-170, Belém, Pará, Brazil 4USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P.O. Box 37012, Washington, DC 20013 Abstract Phylogenetic analysis of the family Furnariidae (Aves: Passeriformes) indicates that the genus Asthenes is polyphyletic, consisting of two groups that are not sister taxa. Pseudasthenes, a new genus of ovenbird, is described for one of these groups. The four species included in the new genus, formerly placed in Asthenes, are P. humicola, P. patagonica, P. steinbachi, and P. cactorum. Key words: Asthenes, Oreophylax, Schizoeaca, phylogeny, taxonomy Asthenes Reichenbach 1853, a genus of the Neotropical avian family Furnariidae, currently contains 22 species of small ovenbirds restricted to Andean and southern South American temperate and subtropical regions, where they inhabit open areas dominated by rocks, shrubs and grasses (Remsen 2003). Members of the genus, commonly known as canasteros, are extremely diverse in behavior, ecology, and nest architecture, suggesting that Asthenes is not monophyletic (Pacheco et al. 1996; Zyskowski & Prum 1999; Remsen 2003; Vasconcelos et al. -

Canyon Canastero Asthenes Pudibunda in Northern Chile

Canyon Canastero Asthenes pudibunda in northern Chile Jay van der Gaast Se describe la observación de un Asthenes pudibunda a 3500 m en Putre, norte de Chile. Existe una serie de observaciones sin publicar de Putre desde agosto 1992, cuando S. N. G. Howell y S. Webb lo hallaron común, sin poder identificarlo positivamente. En agosto–septiembre y noviembre 1996, los mismos observadores lo encontraron nuevamente común en Putre, esta vez confirmando la identificación, efectuando numerosas grabaciones y estableciendo su presencia en otras varias localidades de la Precordillera de Arica. Estos son los primeros registros fuera de Perú. On 3 October 1995, while birding a gorge at Putre, northern Chile, an unfamiliar call alerted Dave Sargaent and myself to the presence of an unknown bird in the shrubbery below us. With a few squeaking sounds, we managed to coax the bird into popping its head out, whereupon, from its buffy supercilium, cinnamon chin and streaked throat and upper breast, we could see it was a canastero. Only two species of Asthenes are known from this region of Chile, and one of these, Dark-winged Canastero A. arequipae, could be eliminated immediately due to the throat and breast streaking. Cordilleran Canastero A. modesta, although similar in plumage has a very different call to the bird we were observing. Following a few seconds of observation, the bird flew a short distance, permitting excellent dorsal views. The large amount of rufous in the bird’s plumage was immediately apparent. The wings were extensively rufous, as was the tail, the latter showing very little dusky on the inner webs. -

Descargar Archivo

ISSN (impreso) 0327-0017 - ISSN (on-line) 1853-9564 NNótulótulasas FAUNÍSTICAS 290 Segunda Serie Junio 2020 AVES DE LA PREPUNA DEL NOROESTE DE ARGENTINA Patricia Capllonch1,2, Fernando Diego Ortiz1,3 y Rebeca Lobo Allende1, 4 1Centro Nacional de Anillado de Aves (CENAA), Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Miguel Lillo 205, San Miguel de Tucumán (4000) Tucumán, Argentina. [email protected] 2Cátedra de Biornitología Argentina, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Miguel Lillo205, San Miguel de Tucumán (4000), Tucumán, Argentina. 3Centro de Rehabilitación de Aves Rapaces (CeRAR), Reserva Experimental Horco Molle, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Miguel Lillo 205, San Miguel de Tucumán (4000), Tucumán, Argentina. 4Universidad Nacional de Chilecito, Campus Los Sarmientos, Ruta Los Peregrinos s/n, Los Sarmientos, Chilecito, La Rioja. RESUMEN. Se analiza la avifauna en 11 localidades de la Prepuna, en el noroeste de la Argentina. Se registraron 165 especies de aves repartidas en 17 órdenes, 35 familias y 119 géneros. Esta riqueza representa el 17% de la avifauna del país, el 35% de la de Tucumán, el 29% de la de Jujuy y el 25% de la de Salta. Las localidades de Prepuna con mayor riqueza de aves fueron Cachi en la provincia de Salta, con 74 especies, El Molle, departamento Tafí, con 63 especies y El Arbolar, Colalao del Valle, con 60 especies, ambas en la provincia de Tucumán. Las especies con presencia constante o regular a lo largo del año con registros de captura en invierno y verano fueron 37 y solo 25 de ellas por su abundancia y constancia estacional son diagnósticas de la Prepuna argentina. -

GAYANA Assessing Climatic and Intrinsic Factors That Drive Arthropod

GAYANA Gayana (2020) vol. 84, No. 1, 25-36 DOI: XXXXX/XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX ORIGINAL ARTICLE Assessing climatic and intrinsic factors that drive arthropod diversity in bird nests Evaluando los factores climáticos e intrínsecos que explican la diversidad de artrópodos dentro de nidos de aves Gastón O. Carvallo*, Manuel López-Aliste, Mercedes Lizama, Natali Zamora & Giselle Muschett Instituto de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Campus Curauma, Avenida Universidad 330, Valparaíso, Chile. *E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Bird nests are specialized structures that act as microrefuge and a source of food for arthropods. Nest arthropod richness and composition may vary according to the nest builder, geographical location and nest size. Because information on nest arthropods is scarce, there are even fewer studies on the drivers of nest arthropod diversity. We characterized arthropod diversity in cup- and dome-shaped nests along a 130 km latitudinal gradient in the mediterranean-type region of Central Chile and, we assessed whether nest dimensions and climatic factors explain richness (alpha-diversity). Then, we evaluated whether climatic differences between sites explain arthropod nest composition (beta-diversity). All collected nests hosted at least one arthropod specimen. We identified 43 taxonomic entities (4.2 entities per nest ± 0.5, mean ± SE, n = 27 nests) belonging to 18 orders and five classes: Arachnida, Diplopoda, Entognatha, Insecta and Malacostraca. We observed differences in nest arthropod richness and composition related to sites but not bird species. Larger nests supported greater arthropod richness. Furthermore, we observed that climatic differences explain the variation in arthropod composition between sites. Nests in the northern region (drier and warmer) mainly hosted Hemipterans and Hymenopterans. -

On the Origin and Evolution of Nest Building by Passerine Birds’

T H E C 0 N D 0 R r : : ,‘ “; i‘ . .. \ :i A JOURNAL OF AVIAN BIOLOGY ,I : Volume 99 Number 2 ’ I _ pg$$ij ,- The Condor 99~253-270 D The Cooper Ornithological Society 1997 ON THE ORIGIN AND EVOLUTION OF NEST BUILDING BY PASSERINE BIRDS’ NICHOLAS E. COLLIAS Departmentof Biology, Universityof California, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1606 Abstract. The object of this review is to relate nest-buildingbehavior to the origin and early evolution of passerinebirds (Order Passeriformes).I present evidence for the hypoth- esis that the combinationof small body size and the ability to place a constructednest where the bird chooses,helped make possiblea vast amountof adaptiveradiation. A great diversity of potential habitats especially accessibleto small birds was created in the late Tertiary by global climatic changes and by the continuing great evolutionary expansion of flowering plants and insects.Cavity or hole nests(in ground or tree), open-cupnests (outside of holes), and domed nests (with a constructedroof) were all present very early in evolution of the Passeriformes,as indicated by the presenceof all three of these basic nest types among the most primitive families of living passerinebirds. Secondary specializationsof these basic nest types are illustratedin the largest and most successfulfamilies of suboscinebirds. Nest site and nest form and structureoften help characterizethe genus, as is exemplified in the suboscinesby the ovenbirds(Furnariidae), a large family that builds among the most diverse nests of any family of birds. The domed nest is much more common among passerinesthan in non-passerines,and it is especially frequent among the very smallestpasserine birds the world over. -

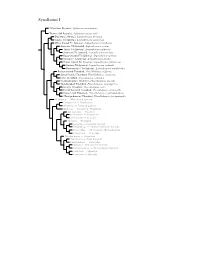

Synallaxini Species Tree

Synallaxini I ?Masafuera Rayadito, Aphrastura masafuerae Thorn-tailed Rayadito, Aphrastura spinicauda Des Murs’s Wiretail, Leptasthenura desmurii Tawny Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura yanacensis White-browed Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura xenothorax Araucaria Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura setaria Tufted Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura platensis Striolated Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striolata Rusty-crowned Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura pileata Streaked Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura striata Brown-capped Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura fuliginiceps Andean Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura andicola Plain-mantled Tit-Spinetail, Leptasthenura aegithaloides Rufous-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus rufifrons Streak-fronted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticeps Little Thornbird, Phacellodomus sibilatrix Chestnut-backed Thornbird, Phacellodomus dorsalis Spot-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus maculipectus Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Freckle-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus striaticollis Orange-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus ?Orange-breasted Thornbird, Phacellodomus ferrugineigula Hellmayrea — White-tailed Spinetail Coryphistera — Brushrunner Anumbius — Firewood-gatherer Asthenes — Canasteros, Thistletails Acrobatornis — Graveteiro Metopothrix — Plushcrown Xenerpestes — Graytails Siptornis — Prickletail Roraimia — Roraiman Barbtail Thripophaga — Speckled Spinetail, Softtails Limnoctites — ST Spinetail, SB Reedhaunter Cranioleuca — Spinetails Pseudasthenes — Canasteros Spartonoica — Wren-Spinetail Pseudoseisura — Cacholotes Mazaria – White-bellied