The War to End War One Hundred Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Renews War on the Meat

-- v. SUGAE-- 96 Degree U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, JUNE 4. Last 24 hours rainfall, .00. Test Centrifugals, 3.47c; Per Ton, $69.10. Temperature. Max. 81; Min. 75. Weather, fair. 88 Analysis Beets, 8s; Per Ton, $74.20. ESTABLISHED JULV 2 1656 VOL. XLIIL, NO. 7433- - HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, TUESDAY, JUNE 5. 1906. PRICE FIVE CENTS. h LOUIS MARKS SCHOOL FUNDS FOSTER COBURN WILL THE ESIDENT SUCCEED BURTON IN KILLED BY RUfl VERY UNITED STATE SENATE RENEWS WAR ON THE AUTO LOW MEAT MEN t - 'is P A Big Winton Machine Less Than Ten Dollars His Message to Congress on the Evils of the , St- .- Over, Crushing Left for Babbitt's 1 Trust Methods Is Turns 4 Accompanied by the -- "1 His Skull. Incidentals, )-- Report of the Commissioner. ' A' - 1 A deplorable automobile accident oc- There are less than ten dollars left jln the stationery and incidental appro- curred about 9:30 last night, in wh'ch ' f. priation for the schol department, rT' Associated Press Cablegrams.) Louis Marks was almost instantly kill- do not know am ' "I what I going to 4-- WASHINGTON, June 5. In his promised message to Congress ed and Charles A. Bon received serious do about it," said Superintendent Bab- (9 yesterday upon the meat trust and its manner of conducting its busi bitt, yesterday. "We pay rents to injury tc his arm. The other occupants the ness, President Kooseveli urged the enactment of a law requiring amount of $1250 a year, at out 1 ! least, stringent inspection of of the machine, Mrs. Marks and Mrs. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

The Campaign to Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald

The Campaign To Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park Historic Context Inventory & Analysis October 2018 2 Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools NHP Campaign The Campaign To Create a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park Historic Context Inventory & Analysis October 2018 Prepared by: EHT TRACERIES, INC. 440 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001 Laura Harris Hughes, Principal Bill Marzella, Project Manager John Gentry, Architectural Historian October 2018 3 Dedication This report is dedicated to the National Parks and Conservation Association and the National Trust for Historic Preservation for their unwavering support of and assistance to the Rosenwald Park Campaign in its mission to establish a Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park. It is also dedicated to the State Historic Preservation Officers and experts in fifteen states who work so tirelessly to preserve the legacy of the Rosenwald Schools and who recommended the fifty-five Rosenwald Schools and one teacher’s home to the Campaign for possible inclusion in the proposed park. Cover Photos: Julius Rosenwald, provided by the Rosenwald Park Campaign; early Rosenwald School in Alabama, Architect Magazine; St. Paul’s Chapel School, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; Sandy Grove School in Burleson County, Texas, 1923, Texas Almanac. Rear Cover Photos: Interior of Ridgeley Rosenwald School, Maryland. Photo by Tom Lassiter, Longleaf Productions; Julius Rosenwald and Booker T. Washington, Rosenwald documentary. 4 Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools NHP Campaign Table of Contents Executive Summary 6 Introduction 8 Julius Rosenwald’s Life and Philanthropy 10 Biography of Julius Rosenwald 10 Rosenwald’s Philanthropic Activities 16 Rosenwald’s Approach to Philanthropy 24 Significance of Julius Rosenwald 26 African American Education and the Rosenwald Schools Program 26 African American Education in the Rural South 26 Booker T. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

The Papers of WEB. Du Bois

The Papers of WEB. Du Bois A Guide by Robert W McDonnell Microfilming Corporation of America A Newh-kTitiws Conipany I981 !NO part of this hook may be reproduced In any form, by Photostat, lcrofllm, xeroqraphy, or any other means, or incorporated into bny iniarmriion ~vtrievrisystem, elect,-onic 01 nwchan~cnl,without the written permission of thc copirl-iqht ownpr. Lopyriqht @ 1481. 3nlversi iy of Mr+sictl~lirtt.~dt AnlhC:~st ISBN/O-667-00650- 8 Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biographical Sketch Scope and Content of the Collection Uu Bois Materials in Other Repositories X Arrangement of the Collection xii Descriptions of the Series xiii Notes on Arrangement of the Collection and Use of the Selective xviii Item List and Index Regulations for Use of W.E.B. Du Bois Microfilm: Copyright Information Microfilm Reel List Selective Item List Selective Index to (hide- Correspondence ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The organization and publication of the Papers of W.E.B. Du Bois has been nade possible by the generous support of the National Endownrent for the Humanities and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission and the ever-available assistance of their expert staffs, eipecially Margaret Child and Jeffrey Field for NEH and Roger Bruns, Sara Jackson, and George Vogt for NHPRC. The work was also in large part made possible by the continuing interest, assis- tance, and support of Dr. Randolph Broniery, Chancellor 1971-79, dnd Katherine Emerson, Archivist, of the University of MassachusettsiAmherst, and of other members of the Library staff. The work itself was carried out by a team consisting, at various times, of Mary Bell, William Brown, Kerry Buckley, Carol DeSousa, Candace Hdll, Jbdith Kerr, Susan Lister, Susan Mahnke, Betsy McDonnell, and Elizabeth Webster. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education

UC Berkeley Berkeley Review of Education Title Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968-2015 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3zq0b64q Journal Berkeley Review of Education, 9(2) Author Patterson, Ryan Publication Date 2020 DOI 10.5070/B89242323 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Available online at http://eScholarship.org/uc/ucbgse_bre Disrupt, Defy, and Demand: Movements Toward Multiculturalism at the University of Oregon, 1968–2015 Ryan Patterson William & Mary Abstract This essay explores the history of activism among students of color at the University of Oregon from 1968 to 2015. These students sought to further democratize and diversify curriculum and student services through various means of reform. Beginning in 1968 with the Black Student Union’s demands and proposals for sweeping institutional reform, which included the proposal for a School of Black Studies, this research examines how the Black Student Union created a foundation for future activism among students of color in later decades. Coalitions of affinity groups in the 1990s continued this activist work and pressured the university administration and faculty to adopt a more culturally pluralistic curriculum. This essay also includes a brief historical examination of the state of Oregon and the city of Eugene, Oregon, and their well-documented history of racism and exclusion. This brief examination provides necessary historical context and illuminates how the University of Oregon’s sparse policies regarding race reflect the state’s historic lack of diversity. Keywords: multicultural, activism, University of Oregon Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ryan Patterson. -

19-04-HR Haldeman Political File

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 19 4 Campaign Other Document From: Harry S. Dent RE: Profiles on each state regarding the primary results for elections. 71 pgs. Monday, March 21, 2011 Page 1 of 1 - Democratic Primary - May 5 111E Y~'ilIIE HUUSE GOP Convention - July 17 Primary Results -- --~ -~ ------- NAME party anncd fiJ cd bi.lc!<ground GOVERNORIS RACE George Wallace D 2/26 x beat inc Albert Brewer in runoff former Gov.; 68 PRES cando A. C. Shelton IND 6/6 former St. Sen. Dr. Peter Ca:;;hin NDPA endorsed by the Negro Democratic party in Aiabama NO SENATE RACE CONGRESSIONAL 1st - Jack Edwards INC R x x B. H. Mathis D x x 2nd - B ill Dickenson INC R x x A Ibert Winfield D x x 3rd -G eorge Andrews INC D x x 4th - Bi11 Nichols INC D x x . G len Andrews R 5th -W alter Flowers INC D x x 6th - John Buchanan INC R x x Jack Schmarkey D x x defeated T ito Howard in primary 7th - To m Bevill INC D x x defeated M rs. Frank Stewart in prim 8th - Bob Jones INC D x x ALASKA Filing Date - June 1 Primary - August 25 Primary Re sults NAME party anned filed bacl,ground GOVERNOR1S RACE Keith Miller INC R 4/22 appt to fill Hickel term William Egan D former . Governor SENATE RACE Theodore Stevens INC R 3/21 appt to fill Bartlett term St. -

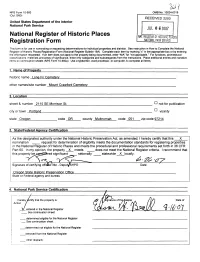

Vv Signature of Certifying Offidfel/Title - Deput/SHPO Date

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUL 0 6 2007 National Register of Historic Places m . REG!STi:ffililSfGRicTLA SES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE — This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Lone Fir Cemetery other names/site number Mount Crawford Cemetery 2. Location street & number 2115 SE Morrison St. not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97214 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties | in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR [Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES to Increase Agricultural Purchasing Power and to Meet the Need of Combating Mr

1942' CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 5241: - ADJOURNMENT .- 1 bill to · provide for recip,rocal .pri-vileges with 1 defense-pz:ogram and.a.reenactmen1 of legisla- ·_ Mr. PRIEST.- Mr.-· sp_eaker·, 1 ·move· F.espt)ct to the filing· of applications, for pat-· 1 1(l.on - si-milar, ~ that -of ~ 1917 and,.. so give· to, ~nts for inventions, and for other purposes;: the young men pf 194:2_ the , protection- .th~r that the Rouse do now adjourn: - -- - to the Committee on ·Patents. fathers had in 1917; to the Committee on . The motion was agree·d· to; accordingly 1756. A letter · from the Secretary of the Military Affairs. · (at 2 o'clock and 12 minutes p. m.) the Interior, transmitting herewith, pursuant to 3065. By Mr. HEIDINGER: Petition of Mrs. House adjourned until tomorrow, Tues-· the act of June 22, 1936 (49 Stat. 1803). a E C. Jacobs and 38 other residents of Flora, day, June 1~, 1942, .at 12 o'clock noon. report dated November 30, 1939, of economic Ill., urging the enactment of Senate bill conditions· affecting certain lands of the' irri- 860; trr the Committee on Military Affairs . gation project under t-he jurisdiction of the 3066. By Mr. LYNCH: Resolution of · the: Oroville-Tonasket irrigation district in the Butchers' Union of Greater New York and COMMITTEE HEARINGS State of Washington; also ~ draft of bill to vicinity, urging increases in pay for postal Cq~MITTEE 0~ PUB~IC ~UILDINGS AND GROUNDS provide relief t_o the own.ers of former Indian employees; to the Committee on the Post There will be a meeting of the com-. -

Springfield News

OnlvorBliyolOroBon Dol)t 01 juuuiu I JrlrL SPRINGFIELD NEWS (Hint Koirniry it. IMI.U 4 irliifttl I. 1mkii, ltrin1-nultorum- SPRINGFIELD, LANE COUNTY, OREGON, THURSDAY, MAY 24, 1917 VOL. XVI. NO. r rt ol t'nnxrn of M rli, my 34 $48 A MONTH FOR WIDOW INTERNED GERMANS TAKE EXERCISE SPUDS SAID TO BE ROTTEN CHRISTIAN CHURCH NO ONE 15 .vMri. W. P. Howill Hat 6077.34 Oe W. B. Cooper Wants His Money Any. EXEMPT Allan for her and Children. way? E, E. Morrison la Defendant MPROVEMENTS 10 FmyilKhi a month will bo W. B. Cooper Is plaintiff In a suit NOW; ALL BETWEEN I A. Mm U. V. Howell, by the stai filed early this week in circuit court Industrial u cell! cut commission which against E. E. Morrison, of Springfield li.vi iii.ulo nwtird in the claim for com In which ho seeks tho recovery of tho BE FINISHED 500 pcmii'ii I; (hu froth of Wm. K. sum of $2046.69, alleged duo on a 21 AND 30 TO Itowpll a ;r'irlitf resident, win quantity of potatoes which tho plain IN tli.O on May f tiMii Iho result of lo tiff sold him. 1 rrculvcd it no Booth-Kell- sa When asked about the suit, Mr. Prooonto Dlfforont Be Siruoturo mill n iMCDnili-- 1G, JMfl. Morrison stated that it really was not Exemptions to Determined Than It Did Mr, Howell loft u widow mid throo hlc affair at all since ho bad been act- After Completion of Regis- ing only as an agent a company Six Wookar Ago. -

Early 2016 Newsletters

Scituate Historical Society 43 Cudworth Road, Scituate, MA 02066, 781-545-1083 On Facebook at www.facebook.com/ScituateHistoricalSociety or at scituatehistoricalsociety.org Making Progress on CPC Projects The Cushing Shay is returned to mint condition while the Lafayette Coach begins its journey back to full health A Trove of Stories Arrives Two months ago a box was delivered by post to the Little Red Schoolhouse. On a Sunday afternoon, the box was opened and a cascade of history tumbled out. The box came from the Franzen family of Scituate and New Hampshire. The materials included ran a gamut from 1840 to 1945. Photographs, letters, portraits, lithographs, and a one of a kind medal were included. See the photos below for a hint at this amazing donation. We can not be more grateful. The Coast Guard of a bygone day An extremely rare medal given to each Scituate sol- dier or sailor who returned from World War 1. This is believed to be William Franzen during the First World War. The North Jetty in ice—1913 Captain George Brown of the Sailors muster at the Dedication of Life Saving service the Monument at Lawson Common The Dr. Harold Edgerton /Graves End Bell Comes to Rest at Scituate Light Thanks are due to many hands for the installation of the Dr. Harold Edgerton /Graves End Bell at Scituate Light in early December. We are in debt to Bob Chessia, Bob Steverman, Steve Litchfield, Scituate Concrete Pipe, and especially the generous team at MIT who coordinated this gift. Pictured with the bell is Gary Tondorf- Dick , Project Manager for MIT Facilities, who had a bell on his hands and knew just where he wanted it to land. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website.