Re-Engineering the M Auritian Social Contract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Items-In-Visits of Heads of States and Foreign Ministers

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page Date 15/06/2006 Time 4:59:15PM S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Expanded Number S-0907-0001 -01 -00001 Title items-in-Visits of heads of states and foreign ministers Date Created 17/03/1977 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0907-0001: Correspondence with heads-of-state 1965-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit •3 felt^ri ly^f i ent of Public Information ^ & & <3 fciiW^ § ^ %•:£ « Pres™ s Sectio^ n United Nations, New York Note Ko. <3248/Rev.3 25 September 1981 KOTE TO CORRESPONDENTS HEADS OF STATE OR GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERS TO ATTEND GENERAL ASSEMBLY SESSION The Secretariat has been officially informed so far that the Heads of State or Government of 12 countries, 10 Deputy Prime Ministers or Vice- Presidents, 124 Ministers for Foreign Affairs and five other Ministers will be present during the thirty-sixth regular session of the General Assembly. Changes, deletions and additions will be available in subsequent revisions of this release. Heads of State or Government George C, Price, Prime Minister of Belize Mary E. Charles, Prime Minister and Minister for Finance and External Affairs of Dominica Jose Napoleon Duarte, President of El Salvador Ptolemy A. Reid, Prime Minister of Guyana Daniel T. arap fcoi, President of Kenya Mcussa Traore, President of Mali Eeewcosagur Ramgoolare, Prime Minister of Haur itius Seyni Kountche, President of the Higer Aristides Royo, President of Panama Prem Tinsulancnda, Prime Minister of Thailand Walter Hadye Lini, Prime Minister and Kinister for Foreign Affairs of Vanuatu Luis Herrera Campins, President of Venezuela (more) For information media — not an official record Office of Public Information Press Section United Nations, New York Note Ho. -

List of Countries and Father of Nation

List of Countries and Father of Nation: Country Founder/Father Afghanistan Ahmad Shah Durrani Argentina Don Jose de San Martín Australia Sir Henry Parkes Bahamas Sir Lynden Pindling Bangladesh Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Bolivia Simón Bolívar Dom Pedro I andJose Bonifacio de Brazil www.homoeoadda.in Andrada e Silva Burma (Myanmar) Aung San Cambodia Norodom Sihanouk Chile Bernardo O'Higgins Republic of China Sun Yat-sen Colombia Simón Bolívar Gustav I of Sweden Sweden www.homoeoadda.in Croatia Ante Starcevic Cuba Carlos Manuel de Cespedes Dominican Republic Juan Pablo Duarte Ecuador Simon Bolivar Ghana Kwame Nkrumah Guyana Cheddi Jagan Haiti www.homoeoadda.in Jean-Jacques Dessalines India Mohandas Karam Chand Gandhi Indonesia Sukarno Iran Cyrus the Great Israel Theodor Herzl Italy Victor Emmanuel II Kenya Jomo Kenyatta Kosovo Ibrahim Rugova Lithuania Jonas Basanavicius Macedonia Krste Misirkov Malaysia Tunku Abdul Rahman Mauritius Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Mexico Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla Mongolia Genghis Khan Namibia Sam Nujoma William the Silent Netherlands www.homoeoadda.in Norway Einar Gerhardsen Pakistan Mohammad Ali Jinnah Panama Simón Bolivar Peru Don Jose de San Martin Portugal Dom Afonso Henriques Republic of Korea Kim Gu Russia Peter I of Russia Saudi Arabia Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia Scotland Donald Dewar Serbia Dobrica Cosic Singapore Lee Kuan Yew Slovenia Primoz Trubar South Africa Nelson Mandela Spain Fernando el Catolico Sri Lanka Don Stephen Senanayake Suriname Johan Ferrier Tanzania Julius Nyerere Turkey Mustafa Kemal Ataturk United Arab Emirates Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan United States of America George Washington Uruguay Jose Gervasio Artigas Venezuela Simon Bolívar Vietnam Ho Chi Minh . -

The Prime Minister of the Republic of India

The Prime Minister of the Republic of India: Honourable Speaker, Sir, Honourable Prime Minister, Distinguished Members of the National Assembly, Ladies and Gentlemen, I would like to thank you for your most gracious words of welcome as also for honouring me with the opportunity to address this august House. This Assembly stands tall, symbolising the resolute commitment of the Mauritian people to representative democracy. The remarkable success of the Mauritian democratic experience seems doubly impressive, given the immense diversity of the multi-lingual, multi-ethnic, multi-religious character of your people. Demographic and social diversity is not an obstacle to democracy, but rather it is its essential counterpart. The natural tendency of our times is towards pluralism within a framework that ensures an inclusive polity and a caring society. There is growing awareness that globalization requires, and in fact demands, an expanding terrain of open, inclusive and diverse societies co-existing in harmony and inter-dependence. Our success in ushering a new paradigm of a co-operative international order depends on the success we achieve in expanding space for multi-cultural societies living in peace, harmony and prosperity. India and Mauritius should lead the way in showing history and humankind that pluralism works, that pluralism is the order of the day and that in embracing pluralism we embrace global security. Mr Speaker, Sir, we live in a world where pluralism is buffeted by forces, which are inimical to peaceful co-existence and harmonious relationships within societies. India and Mauritius, through the rich and successful experience of managing diversity and pluralism in an inclusive framework, stand out as beacons of hope for the future. -

HISTORY & GEOGRAPHY Time: 1 Hour

mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius mauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritiusexaminationssyndicatemauritius -

1643Rd GENERAL PLENARY MEETING

United Nations 1643rd GENERAL PLENARY MEETING ASSEMBLY Wednesday, 44 Apri11968, TIFENT1'·SECOSI> SESSION at 3 pomo Official Records NEW YORK CONTENTS 7. At the beginning of the session the General As Page sembly referred item 28 (Non-proliferation ofnuclear Resumption of the twenty-second session. •••• 1 weapons) to the First Committee, requesting it to report to the plenary. Organization of work ••• 0 •••• 0 • • • • • • • • • 1 8. As a result of consultations which 1 have held, Agenda item 99: 1 understand that Member States wish the Committee Admission of new Members to the United so to organize its work as to ensure that this item Nations (concluded). ••••••••••••.•.• 4 is given careful scrutiny on the basis of the relevant documentation. If 1 hear no obj ection, may 1 take it President: Mr. Corneliu MANESCU (Romania). that the Aseembly still wishes agenda item 28 @} to be dealt with by the First Committee? It was s 0 decided. Resumption of the twenty-second session 9. The PRESIDENT (translated from French): With 1, The PRESIDENT (translated fro.m French): 1 de regard to item 64 (Question of South West Africa), clare open the 1643rd plenary mee~ing with which the 1 wish to inform the Assembly that the Chairman of General Assembly resumes its twenty-second session. the Afro-Asian Group, R.E. Ambassador Shahi of Pakistan, has conveyed ta me the Groupls· request 2. It gives me much pleasure to welcome the repre that the General Assembly begin its consideration of sentatives who have come here to take part in our this item at once, on the understanding that plenary work. -

Is Tanzania a Success Story? a Long Term Analysis

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES IS TANZANIA A SUCCESS STORY? A LONG TERM ANALYSIS Sebastian Edwards Working Paper 17764 http://www.nber.org/papers/w17764 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2012 Many people helped me with this work. In Dar es Salaam I was fortunate to discuss a number of issues pertaining to the Tanzanian economy with Professor Samuel Wangwe, Professor Haidari Amani, Dr. Kipokola, Dr. Hans Hoogeveen, Mr. Rugumyamheto, Professor Joseph Semboja, Dr. Idris Rashid, Professor Mukandala, and Dr. Brian Cooksey. I am grateful to Professor Benno Ndulu for his hospitality and many good discussions. I thank David N. Weil for his useful and very detailed comments on an earlier (and much longer) version of the paper. Gerry Helleiner was kind enough as to share with me a chapter of his memoirs. I thank Jim McIntire and Paolo Zacchia from the World Bank, and Roger Nord and Chris Papagiorgiou from the International Monetary Fund for sharing their views with me. I thank Mike Lofchie for many illuminating conversations, throughout the years, on the evolution of Tanzania’s political and economic systems. I am grateful to Steve O’Connell for discussing with me his work on Tanzania, and to Anders Aslund for helping me understand the Nordic countries’ position on development assistance in Africa. Comments by the participants at the National Bureau of Economic Research “Africa Conference,” held in Zanzibar in August 2011, were particularly helpful. I am grateful to Kathie Krumm for introducing me, many years ago, to the development challenges faced by the East African countries, and for persuading me to spend some time working in Tanzania in 1992. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright

Rohatgi, Rashi (2012) Fighting cane and canon: reading Abhimanyu Unnuth's Hindi poetry in and outside of literary Mauritius. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/16627 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Fighting Cane and Canon: Reading Abhimanyu Unnuth’s Hindi Poetry In and Outside of Literary Mauritius Rashi Rohatgi Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Languages and Cultures of South Asia 2012 Supervised by: Dr. Francesca Orsini and Dr. Kai Easton Departments of Languages and Cultures of South Asia School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 Declaration for PhD Thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all of the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. -

Ghana's Economic and Agricultural Transformation

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 30/7/2019, SPi 3 Strong Democracy, Weak State The Political Economy of Ghana’s Stalled Structural Transformation Danielle Resnick 3.1 Introduction What are the political and institutional factors that enable governments to pursue policies to promote economic and agricultural transformation? Sus- taining growth, achieving inclusive development, and promoting structural transformation require qualitatively different, albeit not necessarily mutually distinct, economic policy interventions. In particular, respecting property rights, investing in broad-based public goods, such as infrastructure, education, and health, and adhering to macroeconomic stability, can be critical “funda- mentals” for, or enablers of, sustainable growth, but they do not necessarily result in structural transformation (see Chapter 2 of this book, and Rodrik 2014). Instead, the latter may be more likely when specific industries are favored, firms are incentivized, and market failures within and across sectors are over- come (see Sen 2015). Hausmann et al. (2008) identify three different types of market failures that need to be overcome in order to achieve transformation: self-discovery externalities (identifying new products that can be produced profitably), coordination externalities (engaging in simultaneous investments upstream and downstream), and missing public inputs (legislation, accredit- ation, and infrastructure). Structural transformation therefore requires more activist government policies beyond providing an enabling environment. However, some of the economic policy levers that are available for address- ing these market failures may be more viable in certain political and institu- tional settings than others. By investing in the economic “fundamentals,” peaceful, democratic societies are typically better at sustaining growth than conflict-ridden, autocratic ones (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Feng 1997; Gerring et al. -

Social Democracy in Mauritius

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository Development with Social Justice? Social Democracy in Mauritius Letuku Elias Phaahla 15814432 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (International Studies) at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Janis van der Westhuizen March 2010 ii Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Signature:……………………….. Date:…………………………….. iii To God be the glory My dearly beloved late sisters, Pabalelo and Kholofelo Phaahla The late Leah Maphankgane The late Letumile Saboshego I know you are looking down with utmost pride iv Abstract Since the advent of independence in 1968, Mauritius’ economic trajectory evolved from the one of a monocrop sugar economy, with the latter noticeably being the backbone of the country’s economy, to one that progressed into being the custodian of a dynamic and sophisticated garment-dominated manufacturing industry. Condemned with the misfortune of not being endowed with natural resources, relative to her mainland African counterparts, Mauritius, nonetheless, was able to break the shackles of limited economic options and one of being the ‘basket-case’ to gradually evolving into being the upper-middle-income country - thus depicting it to be one of the most encouraging economies within the developing world. -

Appendix I: Acronyms

Appendix I: Acronyms AAF-SAP African Alternative Framework to Structural Adjustment Programmes AAPC All-African Peoples Conference AAPSO Afro-Asian People's Solidarity Organization ACP Group African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group ADB African Development Bank ADP agricultural development program AEF Afrique Equatoriale Fran~aise (French Equatorial Africa) AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC African National Congress AOF Afrique Occidentale Fran~aise (French West Africa) APEC Asian-Pacific Economic Cooperation AZAPO Azanian Peoples' Organization AZASO Azanian Students' Organization BCM Black Consciousness Movement BOSS Bureau of State Security CC Chama Cha Mapinduzi CEAO Economic Community of West Africa CFA African Financial Community CIA Central Intelligence Agency CIAS Conference of Independent African States CIEC Conference on International Economic Cooperation CODES A Convention for a Democratic South Africa COMECON Council for Mutual Economic Assistance COSAG Concerned South Africans Group 499 500 Acronyms COSAS Congress of South African Students COSATU Congress of South African Trade Unions CPP Convention People's party CUSA Council of Unions of South Africa DAC Development Assistance Committee DFI direct foreign investment DROC Democratic Republic of Congo, typically referred to as Congo, or Congo-Kinshasa EAC East African Community ECA Economic Commission for Africa ECCAS Economic Community of Central African States ECOMOG ECOWAS Cease-Fire Monitoring Group ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States EDF European Development -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

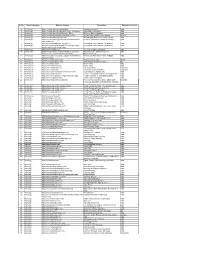

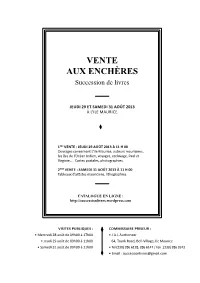

Vente Aux Enchères Succession De Livres

VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES Succession de livres JEUDI 29 ET SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À L’ILE MAURICE. 1ÈRE VENTE : JEUDI 29 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice, auteurs mauriciens, les îles de l’Océan Indien, voyages, esclavage, Paul et Virginie,…. Cartes postales, photographies. 2EME VENTE : SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Tableaux d’artistes mauriciens, lithographies. CATALOGUE EN LIGNE : http://successionlivres.wordpress.com VISITES PUBLIQUES : COMMISSAIRE PRISEUR : • Mercredi 28 août de 09h00 à 17h00 • J.A.L Auctioneer • Jeudi 29 août de 09h00 à 11h00 64, Trunk Road, Bell-Village, Ile Maurice • Samedi 31 août de 09h00 à 11h00 • Tel (230) 286 6128, 286 6147 / Fax : (230) 286 2673 • Email : [email protected] Information Une vente aux enchères concernant la succession de livres de M. …, bibliophile d’ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice ou publiés à L’Ile Maurice, se tiendra à L’Ile Maurice : • 1ÈRE VENTE : JEUDI 29 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Ouvrages concernant L’Ile Maurice, auteurs mauriciens, les îles de l’Océan Indien, voyages, esclavage, Paul et Virginie,…. Cartes postales, photographies. •2EME VENTE : SAMEDI 31 AOÛT 2013 À 11 H 00 Tableaux d’artistes ayant vécu à Maurice, lithographies. - Le lieu de vente vous sera communiqué dans les meilleurs délais. Les ouvrages seront vendus par lots, organisés par thématiques (ex : histoire, esclavage, auteur, Madagascar, agriculture, religion,…). Un catalogue des lots est disponible en ligne à l’adresse suivante : http://successionlivres.wordpress.com où vous pouvez avoir accès à un moteur de recherche. Il est également téléchargeable en format pdf ici.