Comics and Comic- Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermedial Communication in Interactive Works: Dialogue Between the Media in the Game Fantasy Final VII

Brazilian Journal of Development 14303 ISSN: 2525-8761 Intermedial Communication in Interactive Works: Dialogue between the Media in the game Fantasy Final VII Comunicação Intermidiática em Obras Interativas: Diálogos entre as Mídias no Jogo Final Fantasy VII DOI:10.34117/bjdv7n2-177 Recebimento dos originais: 27/01/2021 Aceitação para publicação: 09/02/2021 Lucas Gonçalves Rodrigues Mestrando em Imagem e Som Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Luiz Ricardo Gonzaga Ribeiro Mestrando em Engenharia de Produção Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Paulo Roberto Montanaro Doutor em Educação Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Leonardo Antônio de Andrade Doutor em Ciências da Computação Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT Intermediality can be defined as the phenomenon in which a work of art appropriates the linguistic resources of two or more media, resulting in something that is potentially new and initially difficult to classify. The understanding of this exchange can be useful to authors who seek to overcome the traditional limits of a particular language, art form or medium. This paper sought to investigate the bibliography on this subject to primarily understand how games present themselves as a complex form of media and then draw parallels that can initiate a bridge between the intermediality theory and the study of contemporary interactive media. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

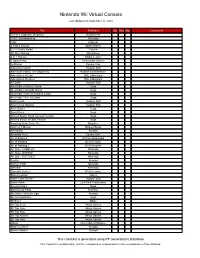

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Compilation List

Sega Genesis Collection Sonic’s Ultimate Genesis Coll. Sega Genesis Classics Coll. 1. Alex Kidd in the Ench. Castle 1. Alex Kidd in the Ench. Castle 1. Alex Kidd in the Ench. Castle 2. Altered Beast 2. Alien Storm 2. Alien Soldier 3. Bonanza Bros. 3. Altered Beast 3. Alien Storm 4. Columns 4. Beyond Oasis 4. Altered Beast 5. Comix Zone 5. Bonanza Bros. 5. Bio-Hazard Battle 6. Decap Attack 6. Columns 6. Bonanza Bros. 7. Ecco the Dolphin 7. Comix Zone 7. Columns 8. Ecco: The Tides of Time 8. Decap Attack 8. Columns III 9. Ecco Jr. 9. Dr. Robotnik’s M. B. Machine 9. Comix Zone 10. Flicky 10. Dynamite Headdy 10. Crack Down 11. Gain Ground 11. Ecco the Dolphin 11. Decap Attack 12. Golden Axe 12. Ecco: The Tides of Time 12. Dr. Robotnik’s M.B. Machine 13. Golden Axe II 13. ESWAT: City under Siege 13. Ecco the Dolphin 14. Golden Axe III 14. Fatal Labyrinth 14. Ecco: The Tides of Time 15. Kid Chameleon 15. Flicky 15. Ecco Jr. 16. Phantasy Star II 16. Gain Ground 16. ESWAT: City under Siege 17. Phantasy Star III 17. Golden Axe 17. Fatal Labyrinth 18. Phantasy Star IV 18. Golden Axe II 18. Flicky 19. Ristar 19. Golden Axe III 19. Gain Ground 20. Shadow Dancer 20. Kid Chameleon 20. Galaxy Force II 21. Shinobi III 21. Phantasy Star II 21. Golden Axe 22. Sonic The Hedgehog 22. Phantasy Star III 22. Golden Axe II 23. Sonic The Hedgehog 2 23. Phantasy Star IV 23. -

Download Sonic Mega Collection Plus Para Pc

Download sonic mega collection plus para pc Download Sonic Mega Collection Plus • Windows Games @ The Iso Zone • The Ultimate Retro Gaming Resource. So this is the pc version of Sonic Mega Collection Plus, it works quite well for a port from a console. You will. AQUI EL LINK DE DESCARGA! este es el link %28djDEVASTATE_. AQUI LES DEJO EL LINK DEL SONIC MEGA COLLECTION PLUS PC MEGA si te gusto el. Tutorial Of How Download SONIC MEGA COLLECTION PLUS Full Pc hijo de puta me haces perder tiempo. Sonic Mega Collection Plus (Español - Mediafire) - Duration: Arcade Bros views · · Sonic Mega. ?urkzvgbb2 aca esta el link. Sonic Mega Collection Plus es una compilación de un solo disco con los siete Ninguno de los juegos se han mejorado específicamente para la PC y se. PC, US. Smcp pc us front Cover. SMCP PC US Manual. PC, UK. SMCP PC Cover. SMCP PC UK Edição de colecionador, Sonic: Mega Collection Plus reúne mais de sete clássicos do Sonic lançados originalmente para console (Mega Drive. LOQUENDO descargar sonic mega collection plus para pc full torrent +Antoni GilBaez si ya es que. LINK PARA LA DESCARGA %28djDEVASTATE_% 3- Luego. games/sonic-mega-collection-plus-2/ Salu2. Haz clic para ver el perfil del usuario. #1 · 22/Mar/, · Editado por Sir_Sonikku Sistema Operativo: Windows XP / Vista / 7. Procesador: Intel [. Relive the memories in the best Sonic games to come from Sega. Download Sonic Mega Collection Plus (USA) - File Size: G (MD5: Note: You will need to use 7-Zip (Windows) or The Unarchiver (Mac OS) to extract this file. -

Lost in the Static?: Comics in Video Games." Intermedia Games—Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality

Lippitz, Armin. "Lost in the Static?: Comics in Video Games." Intermedia Games—Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality. Ed. Michael Fuchs and Jeff Thoss. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 115–132. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501330520.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 02:17 UTC. Copyright © Michael Fuchs, Jeff Thoss and Contributors 2019. You may share this work for non- commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 5 Lost in the Static? Comics in Video Games Armin Lippitz omics have attracted more and more attention in mainstream culture. As a C result, the estimated market size of the medium in North America has doubled since 1997. 1 One reason for this growing interest in the medium is, without a doubt, the success of cinematic adaptations of comic books. However, video games have experienced an even bigger boom in popularity in recent years. Indeed, global games revenues have been growing and have effectively caught up with the movie industry. A cause for, as much as a result of, the increased success of these two media is their integration into transmedia storyworlds. These networks of texts, which collectively tell a continuous story distributed over various media outlets, have become routine for most mainstream, blockbuster titles, regardless of the initial core text’s medium. Comics and video games seem to be particularly well suited for transmedia explorations because they have always tapped into the potentials of expanding their storyworlds and extending their experiences across media, as Hans-Joachim Backe has argued. -

Uk English ...2

® ™ UK ENGLISH ............................................... 2 FRANÇAIS ................................................... 4 DEUTSCH .................................................... 6 ITALIANO ..................................................... 8 ESPAÑOL ..................................................... 10 US ENGLISH ................................................ 12 The SEGA MEGA DRIVE is known as the SEGA GENESIS in the U.S. SEGA MEGA DRIVE CLASSICS COMIX ZONE™ GENRE: Brawler PLAYERS: 1 Sketch Turner is in it up to his inkwell. Mortus is drawing ADvANCED CONTROLs horrendous creatures to battle Sketch in every panel of the strip. PICK UP ITEMS Press the D-button down over the item. If Mortus destroys Sketch, that megalomaniac mutant will become real SERIAL DOUBLE PUNCH and earth will be doomed to his rule! Press the D-button forward, then Action. But there is hope. Now that he’s a comic book superhero, Sketch SERIAL HIGH KICK TORNADO can kick some serious butt. Instantly, Sketch can fight like a one-man Press the D-button diagonally up and forward, followed by Action. mercenary platoon! SERIAL LOW KICK Press the D-button diagonally down and forward, followed by Action. GAME CONTROLLER COMPATIBILITY UPPERCUT Press the D-button up, then Action. any windows compatible game controller can be used with the SeGa Mega Drive Classics games, as long as it has a D-pad and a minimum of 4 other assignable buttons. The game will recognise any number of FLOOR SWEEP controllers attached to your PC, and they can be assigned to either Player 1 or Player 2. Press the D-button down, then Action. SERIAL DOUBLE PUNCH Please refer to the documentation that came with your game controller for information on how to install it on Press the D-button forward, then Action. -

Game Comics: an Analysis of an Emergent Hybrid Form

Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics ISSN: 2150-4857 (Print) 2150-4865 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcom20 Game comics: an analysis of an emergent hybrid form Daniel Merlin Goodbrey To cite this article: Daniel Merlin Goodbrey (2015) Game comics: an analysis of an emergent hybrid form, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 6:1, 3-14, DOI: 10.1080/21504857.2014.943411 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2014.943411 Published online: 02 Sep 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 202 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcom20 Download by: [Wesleyan University] Date: 24 August 2017, At: 11:29 Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 2015 Vol . 6, No. 1, 3–14, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2014.943411 Game comics: an analysis of an emergent hybrid form Daniel Merlin Goodbrey* School of Creative Arts, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK (Received 23 December 2013; accepted 3 July 2014) There has long been a shared history of visual influence and narrative crossover between comics and videogames. Taking this history into account, this article provides a critical examination of the newly emergent medium of game comics. A game comic can be defined as a game that takes the underlying structure and language of comics as the basis for its gameplay. The article presents a case study on two prototype game comics that were created as a practice-lead enquiry into the potential of the form. -

Copy of Games11111111111.Xlsx

Name System Region Case Manual 3DO Interactive Sampler 4 3DO USA No No Alone in the Dark 2 3DO USA No No Battle Chess 3DO USA No No BladeForce 3DO USA No No Crime Patrol 3DO USA No No Dragon's Lair 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Fifa International Soccer 3DO USA No No Flying Nightmares 3DO USA No No Gex 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Gex 3DO USA Yes Yes Gex 3DO USA No No Panasonic Special CD-Rom 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Policenauts 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Psychic Detective 3DO USA No No Puzzle Bobble 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Quarantine 3DO USA No No Road Rash 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Samurai Showdown 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Shockwave 3DO USA No No Shockwave 2: Beyond the Gate 3DO USA No No Space Ace 3DO USA No No Star Fighter 3DO USA No No Street Fighter II 3DO Japanese Yes Yes Super Street Fighter II Turbo 3DO USA No No The Last Bounty Hunter 3DO USA No No Twisted: The Game Show 3DO USA No No VR Stalker 3DO USA No No Waialae Country Club 3DO USA No No Way of the Warrior 3DO USA No No Wing Commander III 3DO USA No No Air-Sea Battle Atari 2600 USA No No Arcade Pinball Atari 2600 USA No No Asteroids Atari 2600 USA No No Atlantis Atari 2600 USA No No Backgammon Atari 2600 USA No No Baseball Atari 2600 USA No No Basic Programming Atari 2600 USA No No Berzerk Atari 2600 USA No No Blackjack Atari 2600 USA No No Brain Games Atari 2600 USA No No Breakout Atari 2600 USA No No Breakout Atari 2600 USA No No Carnival Atari 2600 USA No No Centipede Atari 2600 USA No No Chase Atari 2600 USA No No Circus Atari Atari 2600 USA No No Codebreaker Atari 2600 USA No No Combat Atari 2600 USA No -

Gaming the Comic Book: Turning the Page on How Comics and Videogames Intersect As Interactive, Digital Experiences

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University MA in English Theses Department of English Language and Literature 2017 Gaming The omicC Book: Turning The aP ge on How Comics and Videogames Intersect as Interactive, Digital Experiences Joseph Austin Thurmond Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/english_etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Thurmond, Joseph Austin, "Gaming The omicC Book: Turning The aP ge on How Comics and Videogames Intersect as Interactive, Digital Experiences" (2017). MA in English Theses. 17. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/english_etd/17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English Language and Literature at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA in English Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please see Copyright and Publishing Info. Gaming The Comic Book: Turning The Page on How Comics and Videogames Intersect as Interactive, Digital Experiences by Joseph Austin Thurmond A Thesis submitted to the faculty of Gardner-Webb University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English Boiling Springs, N.C. 2017 Approved by: __________________________ Dr. Jennifer Buckner, Advisor __________________________ Dr. Shana Hartman __________________________ Dr. Shea Stuart TABLE -

Accepted Manuscript Version

Research Archive Citation for published version: Daniel Boodbrey, “Game Comics: An analysis of an emergent hybrid form”, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, Vol. 6(1): 3-14, September 2014. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2014.943411 Document Version: This is the Accepted Manuscript version. The version in the University of Hertfordshire Research Archive may differ from the final published version. Users should always cite the published version of record. Copyright and Reuse: Published by Taylor & Francis. © 2017 Informa UK Limited. This Manuscript version is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Enquiries If you believe this document infringes copyright, please contact the Research & Scholarly Communications Team at [email protected] Game Comics: An Analysis of an Emergent Hybrid Form Daniel Merlin Goodbrey School of Creative Arts University of Hertfordshire Hatfield, UK 26 Birds Close Welwyn Garden City Hertfordshire AL7 4AR Tel: 07799 037 190 [email protected] Biography Daniel Merlin Goodbrey is a lecturer in Narrative and Interaction Design at The University of Hertfordshire in England. A prolific and innovative comic creator, Goodbrey has gained international recognition as a leading expert in the field of experimental digital comics. Daniel Merlin Goodbrey [email protected] Page 1 of 14 Game Comics: An Analysis of an Emergent Hybrid Form Daniel Merlin Goodbrey School of Creative Arts, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, UK There has long been a shared history of visual influence and narrative crossover between comics and videogames.