Accepted Manuscript Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Examining Female Gamers' Perceptions and Attitudes of Behaviors in the Gaming Community

Running head: FEMALE GAMERS AND SEXUAL HARASSMENT 1 Examining Female Gamers’ Perceptions and Attitudes of Behaviors in the Gaming Community Michele Desirée Evanson Marietta College A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Marietta College Psychology Department In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Psychology May 2017 FEMALE GAMERS AND SEXUAL HARASSMENT 2 FEMALE GAMERS AND SEXUAL HARASSMENT 3 Abstract In recent years video games have grown into a mainstream pastime. The internet and use of social media have made it easier for gamers to interact, and have made communications open to the public. Recent public displays of harassment have led to discussions of sexism in gaming culture. Gaming is generally considered a male dominated culture, and previous research on the impact of video games on problematic behavior predominantly focused on males. We now know female gamers are a prominent demographic (ESA, 2015; Stuart, 2014), and since they are often the target of sexual harassment it is important to examine their perspective of these behaviors. This study surveyed female gamers in order to identify their general attitudes towards and perceptions of sexual harassment. Similarly to previous research, attitudes and perceptions of sexual harassment were negatively related; greater tolerance towards sexual harassment led to identifying fewer behaviors as sexual harassment. The hypothesis that participants who predominantly played Mature rated games would lead to more tolerant attitudes of sexual harassment was not upheld. Exploratory analysis found that the role-playing and sports genres were significantly related to general sexual harassment attitudes. Interest in the sports genre was positively related to tolerant attitudes of sexual harassment. -

Intermedial Communication in Interactive Works: Dialogue Between the Media in the Game Fantasy Final VII

Brazilian Journal of Development 14303 ISSN: 2525-8761 Intermedial Communication in Interactive Works: Dialogue between the Media in the game Fantasy Final VII Comunicação Intermidiática em Obras Interativas: Diálogos entre as Mídias no Jogo Final Fantasy VII DOI:10.34117/bjdv7n2-177 Recebimento dos originais: 27/01/2021 Aceitação para publicação: 09/02/2021 Lucas Gonçalves Rodrigues Mestrando em Imagem e Som Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Luiz Ricardo Gonzaga Ribeiro Mestrando em Engenharia de Produção Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Paulo Roberto Montanaro Doutor em Educação Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Leonardo Antônio de Andrade Doutor em Ciências da Computação Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT Intermediality can be defined as the phenomenon in which a work of art appropriates the linguistic resources of two or more media, resulting in something that is potentially new and initially difficult to classify. The understanding of this exchange can be useful to authors who seek to overcome the traditional limits of a particular language, art form or medium. This paper sought to investigate the bibliography on this subject to primarily understand how games present themselves as a complex form of media and then draw parallels that can initiate a bridge between the intermediality theory and the study of contemporary interactive media. -

Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book

PENNY ARCADE: VOLUME 8: MAGICAL KIDS IN DANGER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Krahulik,Jerry Holkins | 112 pages | 11 Sep 2012 | Oni Press,US | 9781620100066 | English | Portland, United States Penny Arcade: Volume 8: Magical Kids in Danger PDF Book The wares of the poor little match girl illuminate her cold world, bringing some beauty to her brief, tragic life. He has a fascination with unicorns , a secret love of Barbies , is a dedicated fan of Spider-Man and Star Wars , and has proclaimed " Jessie's Girl " to be the greatest song of all time. Thompson proceeded to phone Krahulik, as related by Holkins in the corresponding news post. The transformation of humanity through nano… More. PC Gamer. Jul 09, Kevin Gentilcore rated it really liked it. Anyway, people probably already know whether or not they like Penny Arcade. Retrieved March 23, Retrieved May 10, Unless you are a major geek like me, you have no idea what Penny Arcade is. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 26, Retrieved May 9, The comics are from , the commentary from , and both are reflecting an industry that moves rapidly, so both are often unintentionally humorous just in regards to how things have fallen out since. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. He has just enough fuel to reach the planet—then he finds that he has a sto… More. Some of these works have been included with the distribution of the game, and others have appeared on pre-launch official websites. Good collection, quick read. Published September 11th by Oni Press first published August 29th Want to Read Currently Reading Read. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew Hes Ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 "I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade. Matthew heS ridan Ames Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Ames, Matthew Sheridan, ""I Am Contemporary!": The Life and Times of Penny Arcade." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

What We Want to See at PAX This Weekend Page 1 of 4 Each Year, PAX Provides the Largest Dedicated Gaming Expos, Catering to Tens of Thousands of Game Fans Every Year

By Amy L. Dickson It’s nearly Labor Day, a long weekend that, along with Memorial Day, bookends the summer months here in the Pacific Northwest. And while some of you readers will head out to the mountains for a last minute camping trip, or over to Seattle Center to catch some live music and comedy at Bumbershoot, we are gearing up for the gaming user experience event of the year: The Penny Arcade Expo. Started in 2004 here in Seattle, PAX is a conference all about gaming. With more events added © BLINK INTERACTIVE, INC. | What We Want to See at PAX This Weekend Page 1 of 4 each year, PAX provides the largest dedicated gaming expos, catering to tens of thousands of game fans every year. PAX Prime will showcase new tech, live gaming, a handheld lounge, tabletop games, PC gaming, panels, concerts, and parties. And Blink will be there. Large crowds and awesome props at a recent PAX event Blinkers Jessica and Brian are both hitting the show over the weekend. Here’s what they are most excited to learn, see, and try: “I’m super excited about attending PAX Prime in Seattle this weekend. It’s my first time going and I can’t wait to see all the upcoming games in the game booths. The thing I am most excited about is getting to try out the Oculus Rift. The last time I tried virtual reality was at Disney Quest in Chicago over a decade ago, and I’m really interested in seeing how far the virtual reality experience has come since then. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

Penny Arcade Volume 3: the Warsun Prophecies by Jerry Holkins for Online Ebook

Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies Jerry Holkins Click here if your download doesn"t start automatically Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies Jerry Holkins Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies Jerry Holkins So it was written, so it shall be. The coming foretold, sealed into the hands of fate by the lips of the prophets from another time. The mystery is revealed and the great plan will now come to its fruition! Its number shall be three. From the far horizons, across the deepest reaches of the ethereal gulf, the thunderous echo of its name shall be heard! PENNY ARCADE! Penny Arcade, the most powerful webcomic in the universe, returns! The third volume of this cultural and supernatural phenomenon, The Warsun Prophecies, brings you every Penny Arcade strip published online in 2002 A.D., encased with the dark secrets of the mad prophets known as Gabe and Tycho. Behold! It has been foretold! Download Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies ...pdf Read Online Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies ...pdf Download and Read Free Online Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies Jerry Holkins From reader reviews: James Lapham: Inside other case, little folks like to read book Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies. You can choose the best book if you appreciate reading a book. Provided that we know about how is important a new book Penny Arcade Volume 3: The Warsun Prophecies. You can add know-how and of course you can around the world by just a book. Absolutely right, since from book you can understand everything! From your country right up until foreign or abroad you can be known. -

A Rundown of What's Going on with Penny Arcade

12/27/2014 A Rundown of What’s Going on with Penny Arcade Now | A Rundown of What’s Going on with Penny Arcade Now Posted on June 20, 2013 by Tami Baribeau It hasn’t been that long since the last time Penny Arcade did something that cast the company in a negative light, but here we are again with another fiasco that’s been making its way around Twitter today. I thought it would be helpful to do a quick rundown of the events from today to make everyone aware of the situation and help answer some questions about why you might want to rethink supporting Penny Arcade, PAX, or anything affiliated with that organization. It all started today when this panel was posted from PAX Australia, titled “Why So Serious? Has the Industry Forgotten That Games Are Supposed to Be Fun?”. The original screencap of the description is below. “Why does the game industry garner such scrutiny from outside sources and within? Every point aberration gets called into question, reviewers are constantly criticised and developers and publishers professionally and personally attacked. Any titillation gets called out as sexist or misogynistic and involve any antagonist race other than Anglo-Saxons and you’re a racist. It’s gone too far and when will it all end? How can we get off the soapbox and work together to bring a new constructive age into fruition?” There is so much wrong with this panel description that I don’t even know where to begin. The idea that games as a medium are exempt from criticism because they’re “supposed to be fun” is ridiculous and immature. -

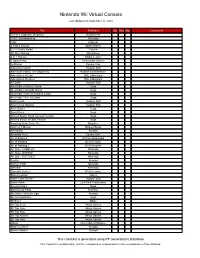

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

DIGITAL GAMING and the MEDIA PLAYGROUND Video Games As a Form of Story

Chapter 3 DIGITAL GAMING AND THE MEDIA PLAYGROUND Video Games as a Form of Story World of Warcraft Ushered in the era of the completely immersive online game Featured a beginner’s guide that read like the narrative of an epic novel Expansions added settings, characters, and play features. Offers players the ability to create their own narratives THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIGITAL GAMING Industrial Revolution Promoted mass consumption Emergence of leisure time Digital games Evolved from their simplest forms in the arcade into four major formats: television, handheld devices, computers, and the Internet MECHANICAL GAMING Coin-operated counter machines First appeared in train depots, hotel lobbies, bars, and restaurants Penny arcade Helped shape future media technology Automated phonographs → jukebox Kinetoscope → movies Bagatelle → pinball machine THE FIRST VIDEO GAMES Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device Key component of the first video games: the cathode ray tube (CRT) Odyssey First home television game Modern arcades Gathered multiple coin-operated games together THE FIRST VIDEO GAMES (CONT.) Atari Created Pong Kept score on the screen Made blip noises when the ball hit the paddles or bounced off the sides of the court First video game popular in arcades Home version was marketed through an exclusive deal with Sears. ARCADES AND CLASSIC GAMES Late 1970s and early 1980s Games like Asteroids, Pac-Man, and Donkey Kong were popular in arcades and bars. Signaled electronic gaming’s potential as a social medium Gaming included the use of joysticks and buttons. Pac-Man featured the first avatar. CONSOLES AND ADVANCING GRAPHICS Consoles Devices specifically used to play video games The higher the bit rating, the more sophisticated the graphics Early consoles Atari 2600 (1977) Nintendo Entertainment System (1983) Sega Genesis (1989) CONSOLES AND ADVANCING GRAPHICS (CONT.) Major home console makers Nintendo Wii Microsoft Xbox and Kinect Sony Playstation series Not every popular game is available on all three platforms. -

Playing to Death • Ken S

Playing to Death • Ken S. McAllister and Judd Ethan Ruggill The authors discuss the relationship of death and play as illuminated by computer games. Although these games, they argue, do illustrate the value of being—and staying—alive, they are not so much about life per se as they are about providing gamers with a playground at the edge of mortality. Using a range of visual, auditory, and rule-based distractions, computer games both push thoughts of death away from consciousness and cultivate a percep- tion that death—real death—is predictable, controllable, reasonable, and ultimately benign. Thus, computer games provide opportunities for death play that is both mundane and remarkable, humbling and empowering. The authors label this fundamental characteristic of game play thanatoludism. Key words: computer games; death and play; thanatoludism Mors aurem vellens: Vivite ait venio. —Appendix Vergiliana, “Copa” Consider here a meditation on death. Or, more specifically, a meditation on play and death, which are mutual and at times even complementary pres- ences in the human condition. To be clear, by meditation we mean just that: a pause for contemplation, reflection, and introspection. We do not promise an empirical, textual, or theoretical analysis, though there are echos of each in what follows. Rather, we intend an interlude in which to ponder the interconnected phenomena of play and death and to introduce a critical tool—terror manage- ment theory—that we find helpful for thinking about how play and death interact in computer games. Johan Huizinga (1955) famously asserted that “the great archetypal activi- ties of human society are all permeated with play from the start” (4).