Lost in the Static?: Comics in Video Games." Intermedia Games—Games Inter Media: Video Games and Intermediality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Designing Motion Comic About Information of Indonesian's

Designing Motion Comic About Information of Indonesian’s Traditional Medicine (Case Study: Djammoe) Y Satrio1* and A Zulkarnain2 1,2Visual Communication Design Department, Faculty of Design, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Jl.MH. Thamrin Boulevard Lippo Village 1100, Tangerang 15810, Indonesia *E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Jamu is an Indonesian traditional health beverage, but among young people, it is deemed out-of-date and a drink for old people. These images take form because young people only get minimal exposure to jamu and because there are modern beverages that they prefer. In this project, the theme of information about jamu will be presented in the form of a digital comic, because the interest in reading textbooks among young people has been gradually diminishing and they prefer reading entertainment books, such as comic books. This project uses a literature study. The literature study is conducted to get information about the theme and the design theories that are going to help with the process of designing the project. The final product of this project is a motion comic. Visual research study and keywords are adjusted to the target audience of this project. The result of the research is used as a guide in the whole process of making the digital comic, from the pre-production to the post-production process. This paper focuses on discussing the application of several design theories in the motion comic project. Keywords. Health, Traditional, Jamu, Young People, Digital Comic 1. Introduction Jamu according to the National Agency of Drug and Food Control of Indonesia is categorized as traditional medicine. -

The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 223 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) George Thomas The Impact of the Illyrian Movement on the Croatian Lexicon Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 S lavistische B e it r ä g e BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER • JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 223 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 GEORGE THOMAS THE IMPACT OF THEJLLYRIAN MOVEMENT ON THE CROATIAN LEXICON VERLAG OTTO SAGNER • MÜNCHEN 1988 George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access ( B*y«ftecne I Staatsbibliothek l Mönchen ISBN 3-87690-392-0 © Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1988 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, GeorgeMünchen Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 FOR MARGARET George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access .11 ж ־ י* rs*!! № ri. ur George Thomas - 9783954792177 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 04:08:27AM via free access 00050383 Preface My original intention was to write a book on caiques in Serbo-Croatian. -

Intermedial Communication in Interactive Works: Dialogue Between the Media in the Game Fantasy Final VII

Brazilian Journal of Development 14303 ISSN: 2525-8761 Intermedial Communication in Interactive Works: Dialogue between the Media in the game Fantasy Final VII Comunicação Intermidiática em Obras Interativas: Diálogos entre as Mídias no Jogo Final Fantasy VII DOI:10.34117/bjdv7n2-177 Recebimento dos originais: 27/01/2021 Aceitação para publicação: 09/02/2021 Lucas Gonçalves Rodrigues Mestrando em Imagem e Som Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Luiz Ricardo Gonzaga Ribeiro Mestrando em Engenharia de Produção Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Paulo Roberto Montanaro Doutor em Educação Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] Leonardo Antônio de Andrade Doutor em Ciências da Computação Universidade Federal de São Carlos Endereço:Rodovia Washington Luís, km 235 - SP-310 São Carlos - São Paulo, Brasil E-mail:[email protected] ABSTRACT Intermediality can be defined as the phenomenon in which a work of art appropriates the linguistic resources of two or more media, resulting in something that is potentially new and initially difficult to classify. The understanding of this exchange can be useful to authors who seek to overcome the traditional limits of a particular language, art form or medium. This paper sought to investigate the bibliography on this subject to primarily understand how games present themselves as a complex form of media and then draw parallels that can initiate a bridge between the intermediality theory and the study of contemporary interactive media. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

William Vance Meester Van Het Detail Woord Vooraf Zenobe Gramme © Michiel De Cleene

MAGAZINE VOOR WIE VAN POSTZEGELS HOUDT 4-2012 N william vance meester van het detail woord vooraf zenobe gramme © Michiel De Cleene BeSte lezer, 3 3 Striptekenaar Vance de zenobe gramme De zomer loopt stilaan tekent zegel ter op zijn einde, en in gelegenheid Van temSifil Temse sluiten ze Strijkt de zeilen het seizoen met een speciale uitgifte 16 knaller af. Aanleiding 6 is de herdenking van ‘België, Stripland’, een heel bijzondere de laatSte in de reekS Met zijn internationaal klinkende gebeurtenis. © SU2012 naam en domicilie in Spanje zet hij 100 jaar geleden, ‘thiS iS Belgium’ 6 © M. De Cleene in 1912, vond er ons gemakkelijk op het verkeerde de Internationale been. Maar Vance is wel degelijk Cutsem Van © Eric Vliegweek voor Watervliegtuigen plaats. Vliegtuigen 14 een striptekenaar van Vlaamse bo- groene innoVatie: waren toen een recent fenomeen en dus lokte dem. Naar aanleiding van Temsifil ‘plak een BoomBlad!’ de Vliegweek heel wat nieuwsgierigen. Dit jaar is tekende hij op vraag van bpost een dat niet anders, want in het weekend van 14 tot en met 16 september kennen de feestelijkheden speciale uitgifte, in de hem type- een hoogtepunt. Eén van de topgebeurtenissen rende hyperrealistische stijl. is ongetwijfeld Temsifil 2012, het Nationale Kampioenschap voor Filatelie dat voor het eerst in 20 jaar opnieuw in Oost-Vlaanderen neerstrijkt. William Vance is het pseudoniem van William Alleen al deze unieke gebeurtenis is een bezoek Van Cutsem en op 78-jarige leeftijd heeft aan de Scheldestad waard. Tegelijk zullen cultuur- hij meer dan 80 albums op zijn naam staan. 2 | en geschiedenisliefhebbers én degenen die altijd Zo werkte hij samen met topscenaristen als | 3 dat kleine jongetje zijn gebleven dat piloot wilde 14 Jean Van Hamme (XIII), Jean Giraud (Mar- worden, genieten van de activiteiten op en rond de shall Blueberry) en Greg (Bruno Brazil). -

La Bande Dessinée XIII : Une Saga Complotiste ?

UNIVERSITE DE LYON UNIVERSITE LUMIERE LYON 2 INSTITUT D’ÉTUDES POLITIQUES DE LYON La Bande dessinée XIII : une saga complotiste ? Apolline Nassour Mémoire de Séminaire Violence et médias 2013 - 2014 Sous la direction de Isabelle Hare et Isabelle Garçin-Marrou Soutenu le 2 septembre 2014 1 2 La Bande dessinée XIII : une saga complotiste ? 3 Sommaire Sommaire ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 8 I. La Bande dessinée comme objet d’étude .................................................................................. 13 I.I Comment analyser une bande dessinée ? ............................................................................ 14 I.I.I Le 9e Art : séquentiel et combinatoire .......................................................................... 14 « L ’Art séquentiel » ....................................................................................................... 14 La combinaison de l’iconique et du verbal ..................................................................... 15 I.I.II Définitions ................................................................................................................... 19 Divisions et subdivisions de la planche .......................................................................... 19 Contenus et contenants des vignettes ............................................................................ -

COMICS and ILLUSTRATIONS PARIS – 14 MARCH 2015 Highlights Exhibited on Preview in NEW YORK from February 27Th to March 4Th

& Press Release ǀ PARIS ǀ 11 February 2015 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE COMICS and ILLUSTRATIONS PARIS – 14 MARCH 2015 Highlights exhibited on preview in NEW YORK from February 27th to March 4th Spirou et FantasioSpirou et Cauvin par Fournier Franquin GREG Janry Morvan * Munuera Nic Roba Tome Vehlmann Yann Yoann © Dupuis 2015 Philippe Francq Uderzo André Franquin Detail of an original illustration for Dior, 2001 Colour cover of Pilote n°489, 20 March 1969 Detail of an original board, Spirou et Fantasio, Estimate: €12,000-15,000 Estimate: €100,000-120,000 Spirou et les Hommes-Bulles, 1960 * © Francq © 2015 Goscinny - Uderzo Estimate: €70,000-80,000 Paris - Following the success of the Comics and Illustration inaugural auction in Paris in April 2014, which realised over €4M, Christie’s will hold a second auction dedicated to sequential art on the upcoming 14 March. This sale, once again carried out in partnership with the Daniel Maghen Gallery, will represent a wide selection of comic artists and heroes, of which the highlights will be exhibited during a preview held at Christie’s New York from February 27th until March 4th 2015. Daniel Maghen, auction expert: «The greatest names in comic history will be celebrated, such as the legendary characters of Hergé, Tintin and Captain Haddock, in an exceptional original cover of the Journal de Tintin, estimated between €350,000 and €400,000, as well as Edgar P. Jacobs’ Blake and Mortimer, and Albert Uderzo’s Astérix and Obélix. The «new classics» will also be represented along with Moebius, whose colour cover of the Incal and a page of Arzach will be offered. -

Bande Dessinée & Illustration

COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE ǀ PARIS ǀ 21 AVRIL 2016 ǀ POUR DIFFUSION IMMÉDIATE BANDE DESSINÉE & ILLUSTRATION Paris, samedi 21 mai 2016 FRANQUIN JEAN-PIERRE GIBRAT GASTON – GALA DE GAFFES (T.2) LE VOL DU CORBEAU, COUVERTURE DE L’INTÉGRALE Estimation: €100.000-120.000 Estimation: €40.000-50.000 Franquin, Jidéhem ©Dargaud-Lombard, 2016 Le Vol du Corbeau par Gibrat © Dupuis 2016 Le 21 mai prochain, Christie’s Paris et Daniel Maghen proposeront leur 3e vente dédiée au 9e art. Depuis le lancement de cette spécialité chez Christie’s en 2014, amateurs et collectionneurs se donnent rendez-vous chaque printemps pour acquérir les œuvres qui ravivent avec joie leurs souvenirs d’enfance, et qui, depuis plusieurs années, ont accédé au statut de 9e art, sollicité par les plus grands musées et les institutions culturelles, privées ou publiques. La vente du mois de mai proposera plus de 200 planches, couvertures et éditions originales pour une estimation totale de plus de €2,5M. Chaque lot a été sélectionné avec soin afin d’offrir un panel quasi exhaustif, représentatif de la bande dessinée d’hier à aujourd’hui. Connaisseurs avisés ou amateurs moins confirmés trouveront ici un vaste choix permettant aisément de démarrer ou compléter une collection, entre auteurs historiques, nouveaux classiques et étoiles montantes de l’illustration contemporaine. Cinq grands piliers de la bande dessinée franco-belge seront également représentés : Morris, Franquin, Hergé, Jacobs et Uderzo. Les couvertures originales seront particulièrement mises à l’honneur. Qu’il s’agisse de couvertures d’albums ou d’hebdomadaires tels Le Journal de Tintin, Le Journal de Spirou, Pilote ou Métal Hurlant, toutes les époques sont représentées, notamment à travers les grands classiques –Franquin, Jacobs, Will et Gotlib–, les nouveaux classiques –Pellerin, Vance, Francq, Bilal, Gibrat– et les contemporains –Brüno, Mallié, Ledroit, Vallée, Meyer. -

Xiii Foro De Sao Paulo; Something to Celebrate in El Salvador Mike Leffert

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository NotiCen Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 2-8-2007 Xiii Foro De Sao Paulo; Something To Celebrate In El Salvador Mike Leffert Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen Recommended Citation Leffert, Mike. "Xiii Foro De Sao Paulo; Something To Celebrate In El Salvador." (2007). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/noticen/ 9482 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NotiCen by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 51510 ISSN: 1089-1560 Xiii Foro De Sao Paulo; Something To Celebrate In El Salvador by Mike Leffert Category/Department: El Salvador Published: 2007-02-08 The XIII Foro de Sao Paulo (FSP) convened in San Salvador Jan. 12-14, bringing together leftist organizations from 33 countries, the majority from Latin America. It was an upbeat and celebratory forum, a departure from the years when the left met to bemoan its losses. This year, the talk turned to predictions of further advances for socialism and an end to neoliberal policies on the continent. "Now we are in a different moment," said Medardo Gonzalez, host of the event. "We are in position to move to the defeat of neoliberalism and not only to defeat it but to go beyond it and construct a new alternative model in Latin America and the Caribbean." Gonzalez is coordinator general of El Salvador's leftist party Farabundo Marti para la Liberacion Nacional (FMLN). -

Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives / Editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, Manga Artist

VISION CULTURAL AND COMMUNICATIVE PERSPECTIVES WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL MANGA VISION MANGA VISION Cultural and Communicative Perspectives EDITED BY SARAH PASFIELD-NEOFITOU AND CATHY SELL WITH MANGA ARTIST QUEENIE CHAN © Copyright 2016 Copyright of this collection in its entirety is held by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell. Copyright of manga artwork is held by Queenie Chan, unless another artist is explicitly stated as its creator in which case it is held by that artist. Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the respective author(s). All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/mv-9781925377064.html Series: Cultural Studies Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Queenie Chan National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Manga vision: cultural and communicative perspectives / editors: Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou, Cathy Sell; Queenie Chan, manga artist. ISBN: 9781925377064 (paperback) 9781925377071 (epdf) 9781925377361 (epub) Subjects: Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects--Japan. Comic books, strips, etc.--Social aspects. Comic books, strips, etc., in art. Comic books, strips, etc., in education. -

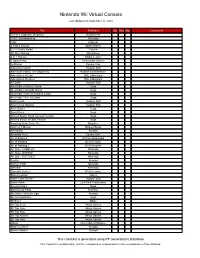

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console

Nintendo Wii Virtual Console Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 101-in-1 Explosive Megamix Nordcurrent 1080° Snowboarding Nintendo 1942 Capcom 2 Fast 4 Gnomz QubicGames 3-2-1, Rattle Battle! Tecmo 3D Pixel Racing Microforum 5 in 1 Solitaire Digital Leisure 5 Spots Party Cosmonaut Games ActRaiser Square Enix Adventure Island Hudson Soft Adventure Island: The Beginning Hudson Entertainment Adventures of Lolo HAL Laboratory Adventures of Lolo 2 HAL Laboratory Air Zonk Hudson Soft Alex Kidd in Miracle World Sega Alex Kidd in Shinobi World Sega Alex Kidd: In the Enchanted Castle Sega Alex Kidd: The Lost Stars Sega Alien Crush Hudson Soft Alien Crush Returns Hudson Soft Alien Soldier Sega Alien Storm Sega Altered Beast: Sega Genesis Version Sega Altered Beast: Arcade Version Sega Amazing Brain Train, The NinjaBee And Yet It Moves Broken Rules Ant Nation Konami Arkanoid Plus! Square Enix Art of Balance Shin'en Multimedia Art of Fighting D4 Enterprise Art of Fighting 2 D4 Enterprise Art Style: CUBELLO Nintendo Art Style: ORBIENT Nintendo Art Style: ROTOHEX Nintendo Axelay Konami Balloon Fight Nintendo Baseball Nintendo Baseball Stars 2 D4 Enterprise Bases Loaded Jaleco Battle Lode Runner Hudson Soft Battle Poker Left Field Productions Beyond Oasis Sega Big Kahuna Party Reflexive Bio Miracle Bokutte Upa Konami Bio-Hazard Battle Sega Bit Boy!! Bplus Bit.Trip Beat Aksys Games Bit.Trip Core Aksys Games Bit.Trip Fate Aksys Games Bit.Trip Runner Aksys Games Bit.Trip Void Aksys Games bittos+ Unconditional Studios Blades of Steel Konami Blaster Master Sunsoft This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database.