Cosmopolitan Archaeologies Material Worlds a Series Edited by Lynn Meskell Lynn Meskell, Editor I Cosmopolitan Archaeologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Parks 2 African Parks

African Parks 2 African Parks African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the total responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities. By adopting a business approach to conservation, supported by donor funding, we aim to rehabilitate each park making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable in the long-term. Founded in 2000, African Parks currently has 15 parks under management in nine countries – Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia. More than 10.5 million hectares are under our protection. We also maintain a strong focus on economic development and poverty alleviation in neighbouring communities, ensuring that they benefit from the park’s existence. Our goal is to manage 20 parks by 2020, and because of the geographic spread and representation of different ecosystems, this will be the largest and the most ecologically diverse portfolio of parks under management by any one organisation across Africa. Black lechwe in Bangweulu Wetlands in Zambia © Lorenz Fischer The Challenge The world’s wild and functioning ecosystems are fundamental to the survival of both people and wildlife. We are in the midst of a global conservation crisis resulting in the catastrophic loss of wildlife and wild places. Protected areas are facing a critical period where the number of well-managed parks is fast declining, and many are simply ‘paper parks’ – they exist on maps but in reality have disappeared. The driving forces of this conservation crisis is the human demand for: 1. -

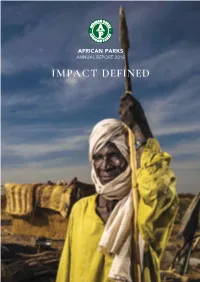

Impact Défini

AFRICAN PARKS RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 IMPACT DÉFINI A vous, hommes et femmes qui mettez vos vies en danger tous les jours pour protéger la faune africaine et les communautés, nous tous à African Parks rendons hommage à votre engagement et saluons vos sacrifices. Couverture: Un ancien de la communauté locale du Parc National de Zakouma, au Tchad. © Brent Stirton Un garde au Parc National de la Garamba, RDC. © Thomas Nicolon African Parks Contenu Message du Président 4 Résumé exécutif du PDG 6 Impact défini 10 Parcs Réserve de Faune de Majete 18 Parc National des Plaines de Liuwa 24 Parc National de la Garamba 30 Zones Humides de Bangweulu 36 Parc National Odzala-Kokoua 42 Parc National de Zakouma 48 Parc National de l’Akagera 54 Ennedi Chinko 60 TCHAD Parc National de Liwonde 66 Parc National Parc National Réserve de Faune de Nkhotakota 72 Pendjari de Zakouma BENIN Parcs en Développement 78 RÉPUBLIQUE Chinko Performances Financières de 2016 80 CENTRAFRICAINE Rapport d’Audit Indépendant 85 Parc National Partenaires Gouvernementaux 86 de la Garamba KENYA Parc National Partenaires Stratégiques 88 Réserve Nationale Odzala-Kokoua RWANDA Organisations et bailleurs individuels 90 RÉPUBLIQUE de Shaba DU CONGO RÉPUBLIQUE Parc Informations institutionnelles 92 DÉMOCRATIQUE African Parks est une organisation sans National de Réserve Nationale Gouvernance 94 but lucratif qui assume la responsabilité DU CONGO l’Akagera directe de la réhabilitation de parcs En commémoration 96 nationaux et d’aires protégées en Zones Humides S’impliquer dans African Parks -

Closing the Gap. Financing and Resourcing of Protected And

Closing the gap Financing and resourcing of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE - BIOPAMA PROGRAMME Financing and resourcing of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa Closing the gap Financing and resourcing of protected and conserved areas in Eastern and Southern Africa I Closing the gap The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN [**or other participating organisations] concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union, the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Group of States, IUCN or other participating organisations. IUCN is pleased to acknowledge the support for this publication produced under the Biodiversity and Protected Areas Management (BIOPAMA) Programme, an initiative of the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) Group of States financed by the 11th European Development Fund (EDF) of the European Union. BIOPAMA is jointly implemented by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. IUCN acknowledges Conservation Capital for providing substantive content to this report. Published by: IUCN Regional Office for Eastern and Southern Africa, in collaboration with the Biodiversity and Protected Areas Management (BIOPAMA) Programme Copyright: © 2020 IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

Global Heritage Blackwell Readers in Anthropology

Global Heritage Blackwell Readers in Anthropology This series fulfils the increasing need for texts that do the work of synthesizing the literature while challenging more traditional or subdisciplinary approaches to anthropology. Each volume offers seminal readings on a chosen theme and provides the finest, most thought‐provoking recent works in the given thematic area. Many of these volumes bring together for the first time a body of literature on a certain topic. The series thus both presents definitive collections and investigates the very ways in which anthro- pological inquiry has evolved and is evolving. 1 The Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader, Second Edition Edited by Jonathan Xavier Inda and Renato Rosaldo 2 The Anthropology of Media: A Reader Edited by Kelly Askew and Richard R. Wilk 3 Genocide: An Anthropological Reader Edited by Alexander Laban Hinton 4 The Anthropology of Space and Place: Locating Culture Edited by Setha Low and Denise Lawrence‐Zúñiga 5 Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology Edited by Nancy Scheper‐Hughes and Philippe Bourgois 6 Same‐Sex Cultures and Sexualities: An Anthropological Reader Edited by Jennifer Robertson 7 Social Movements: An Anthropological Reader Edited by June Nash 8 The Cultural Politics of Food and Eating: A Reader Edited by James L. Watson and Melissa L. Caldwell 9 The Anthropology of the State: A Reader Edited by Aradhana Sharma and Akhil Gupta 10 Human Rights: An Anthropological Reader Edited by Mark Goodale 11 The Pharmaceutical Studies Reader Edited by Sergio Sismondo and Jeremy A. Greene 12 Global Heritage: A Reader Edited by Lynn Meskell Global Heritage: A Reader Edited by Lynn Meskell This edition first published 2015 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. -

Pendjari African Parks | Annual Report 2017 83

82 THE PARKS | PENDJARI AFRICAN PARKS | ANNUAL REPORT 2017 83 BENIN Pendjari National Park 4,800 km2 African Parks Project since 2017 Government Partner: Government of Benin Government of Benin, National Geographic Society, The Wyss Foundation and The Wildcat Foundation were major funders in 2017 A herd of some of the 1,700 elephants that live within the W-Arly-Pendjari landscape. © Jonas van de Voorde 84 THE PARKS | PENDJARI AFRICAN PARKS | ANNUAL REPORT 2017 85 Pendjari JAMES TERJANIAN | PARK MANAGER BENIN – Pendjari National Park is one of the most recent parks and the first within West Africa to fall under our management. Pendjari which is situated in the northwest of Benin and measures 4,800 km2. It is an anchoring part of the transnational W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) complex, spanning a vast 35,000 km2 across three countries: Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. It is the biggest remaining intact ecosystem in the whole of West Africa and the last refuge for the region’s largest remaining population of elephant and the critically endangered West African lion, of which fewer than 400 adults remain and 100 of which live in Pendjari. Pendjari is also home to cheetah, various antelope species, buffalo, and more than 460 avian species, and is an important wetland. But this globally important reserve has been facing major threats, including poaching, demographic pressure on surrounding land, and exponential resource erosion. But the Benin Government wanted to change this trajectory and chart a different path for this critically important landscape within their borders. In September 2016, after a visit to Akagera National Park in Rwanda, which has been managed by African Parks since 2016, the Benin Director of Heritage and Tourism (APDT) approached African Parks to explore opportunities to revitalise and protect this landscape, and help the Government realise the tourism potential of Pendjari under their national plan “Revealing Benin”. -

African Parks Pdf for Web.Indb

AFRICAN PARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016 IMPACT DEFINED “ To our men and women who put their lives on the line every day to protect Africa’s wildlife and safeguard communities, we at African Parks pay ɯɞȓǤɸɯDZɯɀʗɀɸɞǥɀȳȳȓɯȳDZȶɯLjȶǫȎɀȶɀɸɞʗɀɸɞղɥLjǥɞȓˌȓǥDZɥ.” Cover: A local community elder from Zakouma National Park, Chad. © Brent Stirton A ranger at Garamba National Park, DRC. © Thomas Nicolon ࣉ African Parks Contents Chairman’s Message 4 CEO’s Executive Summary 6 Impact Defined 10 Parks Majete Wildlife Reserve 18 Liuwa Plain National Park 24 Garamba National Park 30 Bangweulu Wetlands 36 Odzala-Kokoua National Park 42 Zakouma National Park 48 Akagera National Park 54 Ennedi Chinko 60 CHAD Liwonde National Park 66 Pendjari Zakouma Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve 72 National Park National Park BENIN Parks in Development 78 CENTRAL 2016 Financial Performance 80 AFRICAN Chinko REPUBLIC Independent Auditor’s Report 85 Garamba Government Partners 86 National Park KENYA Odzala-Kokoua Strategic Partners 88 Shaba National National Park RWANDA Organisational and Individual Funders 90 CONGO DEMOCRATIC Reserve REPUBLIC OF Institutional Information 92 CONGO Akagera African Parks is a non-profit National ʹΦȉɫʁʜʟɔɷɆʦ Governance 94 organisation that takes on direct Park National Reserve In Remembrance 96 responsibility for the rehabilitation of national parks and protected areas in Bangweulu Get Involved with African Parks 97 partnership with governments and local Wetlands MALAWI communities. We currently have Nkhotakota mandates to manage 10 national parks Wildlife Reserve Liuwa Plain ZAMBIA and protected areas with a combined National Park Liwonde area of six million hectares in seven National Park countries: Bazaruto Majete Wildlife • Chad Archipelago Reserve • Central African Republic (CAR) National Park • The Republic of Congo MOZAMBIQUE • Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) • Rwanda • Malawi • Zambia We are working towards growing our portfolio and increasing the number of parks under management. -

Past Mastering in the New South Africa

THE NATURE OF HERITAGE THE NATURE OF HERITAGE THE NEW SOUTH AFRICA LYNN MESKELL A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication This edition fi rst published 2012 © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing. Registered Offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offi ces 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/ wiley-blackwell. The right of Lynn Meskell to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. -

Report:African Parks

REPORT: AFRICAN PARKS Back to the fuTuRe Twenty years ago ecide which tree you’re convinced us we would do better to retreat going to climb – quickly.” than to rush up a tree: my fleeting glimpse of the Majete region of Dorian whispered his her among the tangled mess of branches and Malawi was a barren instructions with a bushes would have to suffice. Despite its “Dpalpable sense of urgency, and with good brevity, my encounter with this increasingly wilderness, its native reason. Climbing trees is apparently the only rare animal, being poached to the edge of animal populations way to escape a charging rhino. extinction, felt a true privilege. About 20m ahead, Shamwari snorted That rhinos are here at all in Majete decimated by poaching. deeply and angrily: her alarm call, warning Wildlife Reserve is thanks to the efforts of us to keep our distance. We’d spent five African Parks, a not-for-profit South African Now, as Sue Watt found, hours since dawn following the tracks of conservation organisation that has been the area is once again black rhinos, trawling across sandy river restoring wildlife to this beautiful corner of beds and grassy slopes, and we’d finally southern Malawi for the past 10 years. In home to elephants, found one obscured by dense thicket, one of Africa’s poorest countries, decades of lions and rhinos, thanks shading itself from the morning sun. poaching and poor policing have taken their According to Dorian Tilbury and his toll, leaving Majete an empty, plundered to the latest pioneering tracking team, Shamwari is a relatively wasteland. -

Curriculum Vitae - Ian Hodder

CURRICULUM VITAE - IAN HODDER Date of Birth: 23rd November 1948 Nationality: British Career Details 1968-71 B.A. degree in Prehistoric Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology, London University. Received First Class Honours Degree. 1971-75 Research leading to Ph.D. at Cambridge University, on the subject of ‘spatial analysis in archaeology'. 1974-77 Lecturer in the Department of Archaeology, University of Leeds. 1977-99 University Assistant Lecturer, University Lecturer (1981), Reader in Prehistory (1990), Professor of Archaeology (1996 - 9) in the Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge. 1999- Professor of Anthropology, Department of Anthropology, Stanford University, and Co-Director and Director of the Archaeology Center (to 2009). Dunlevie Family Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences (2002-) Other Appointments and Fellowships 1984 - 1989 Adjunct Assistant Professor of Anthropology at State University of New York, Binghamton. 1986 - 1994 Adjunct Professor and Visiting Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. 1980 (6 months) Visiting Professor, Van Giffen Institute for Pre- and Proto-history, Amsterdam. 1985 (6 months) Visiting Professor, University of Paris I -Sorbonne (U.E.R. d'Art et d'Archéologie). 1987(6 months) Fellow at Centre for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, Stanford, California. 1990 - 2001 Fellow of Darwin College, Cambridge. 1996 - Fellow of the British Academy. 1 2005 – 2006 Guggenheim Fellow. 2007 - Honorary Professor, Institute of Archaeology, University College, London. 2009 (3 months) Visiting Fellow, Magdalen College, Oxford. 2010 (3 months) Visiting Professor, Maison des Sciences de l’Homme and Associate Professor at University of Paris I –Sorbonne. 2010 (6 months) Senior Residential Fellow in Research Center for Anatolian Civilization, Koç University, Istanbul. -

RESTORATION Nature’S Return

RESTORATION Nature’s Return African Parks Annual Report 2017 Contents INTRODUCTION 2 The African Parks Portfolio 4 Chairman’s Message: Robert-Jan van Ogtrop 6 CEO’s Letter & Executive Summary: Peter Fearnhead 12 Restoration: Nature's Return 18 In Remembrance THE PARKS 22 Majete Wildlife Reserve, Malawi 28 Liuwa Plain National Park, Zambia 34 Garamba National Park, DRC 40 Bangweulu Wetlands, Zambia 46 Odzala-Kokoua National Park, Congo 52 Zakouma National Park, Chad 58 Akagera National Park, Rwanda 64 Chinko, Central African Republic 70 Liwonde National Park, Malawi 76 Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve, Malawi 82 Pendjari National Park, Benin 88 Parks in Development OUR PARTNERS 94 Government Partners 96 Strategic Funding Partners 100 Organisational & Individual Funders 102 Institutional Information: Our Boards FINANCIALS 106 2017 Financial Performance 111 Summary Financial Statements 112 Governance IBC Get Involved Three rangers patrol Zakouma in Chad on horseback. © Kyle de Nobrega Cover: An Abyssinian roller in Zakouma in Chad. © Marcus Westberg 2 OUR PORTFOLIO AFRICAN PARKS | ANNUAL REPORT 2017 3 Our Portfolio African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation, founded in 2000, that takes on the complete responsibility for the rehabilitation and long- term management of national parks and protected areas in partnership with governments and local communities. Our aim is to rehabilitate each park, making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable long into the future. At the close of 2017, African Parks had 14 parks under management in nine countries, covering 10.5 million hectares (40,540 square miles) and representing seven of the 11 ecological biomes in Africa. This is the largest and most ecologically diverse amount of land under protection for any one NGO on the continent. -

Charting a Course for Nature

8 INTRODUCTION | CEO’S LETTER & EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AFRICAN PARKS 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 9 Charting a Course for Nature CEO’S LETTER & EXECUTIVE SUMMARY | PETER FEARNHEAD I have been asked many times how Covid-19 has security, where wildlife populations increased, schools affected conservation and my answer remains the same: and clinics functioned, social enterprises were invested in, conservation was in crisis before this pandemic, it and people not just persisted, but thrived. These has remained so throughout, and will continue results were in stark contrast to a recent report to be once we emerge from it. Covid-19 just by the International Union for Conservation shone a spotlight on the extent of the crisis. of Nature (IUCN) and others that more than half of the protected areas in Africa were 2020 was supposed to be the super-year for forced to cut back on protection measures, biodiversity. And in a twisted way it might and more than 25% of rangers lost their prove to be just that. While Covid-19 caused the income. It is because of the resilience of our cancellation of global events that would set targets model, our full accountability, strong governance, to shape the next 10 years for the environment, instead, and long-term funding solutions made possible by many Covid-19 and the global economic lockdown brought our of our funders, that the landscapes managed by African connectedness and dependability on nature into painfully Parks remained protected, while delivering life-altering clear focus – at a truly universal level. It has elevated the benefits to thousands of people. -

African Parks Annual Report: 2015

African Parks Annual Report 2015 CONSERVATION AT SCALE Garamba National Park, DRC – Andrew Brukman African Parks Annual Report 2015 | 1 To our men we have lost in the fight to protect Africa’s wildlife and safeguard communities, and to those who put their lives on the line each and every day, we pay tribute to your commitment and honour your sacrifice. Your friends and family at African Parks 2 Ennedi chad Zakouma National Park Gambella central Chinko african National Park republic ethiopia Garamba National Park Odzala-Kokoua Million National Park congo rwanda Akagera Hectares National Park 6 democratic republic of congo African Parks is a non-profit organisation that takes on direct responsibility for the Bangweulu rehabilitation of National Parks and Wetlands Protected Areas in partnership with Nkhotakota governments and local communities. Wildlife Reserve malawi We currently have mandates to manage zambiazzazamamambibbiaiaia Liwonde 10 National Parks and Protected Areas Majete National Park Liuwa Plain Wildlife with a combined area of six million National Park Reserve hectares in seven countries: • Chad • Central African Republic (CAR) • Republic of Congo • Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) • Rwanda • Malawi • Zambia We also currently have an MoU to assess opportunities in Ennedi, Chad and a tripartite agreement to assess opportunities in Gambella, Ethiopia. Akagera National Park, Rwanda – Bryan Havemann African Parks Annual Report 2015 | 3 CONTENTS 2015 in Focus 4 Chairman’s Message 6 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 8 Institutional