Closing the Gap. Financing and Resourcing of Protected And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Profile Republic of Zambia Giraffe Conservation Status Report

Country Profile Republic of Zambia Giraffe Conservation Status Report Sub-region: Southern Africa General statistics Size of country: 752,614 km² Size of protected areas / percentage protected area coverage: 30% (Sub)species Thornicroft’s giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis thornicrofti) Angolan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis) – possible South African giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis giraffa) – possible Conservation Status IUCN Red List (IUCN 2012): Giraffa camelopardalis (as a species) – least concern G. c. thornicrofti – not assessed G. c. angolensis – not assessed G. c. giraffa – not assessed In the Republic of Zambia: The Zambia Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) is mandated under the Zambia Wildlife Act No. 12 of 1998 to manage and conserve Zambia’s wildlife and under this same act, the hunting of giraffe in Zambia is illegal (ZAWA 2015). Zambia has the second largest proportion of land under protected status in Southern Africa with approximately 225,000 km2 designated as protected areas. This equates to approximately 30% of the total land cover and of this, approximately 8% as National Parks (NPs) and 22% as Game Management Areas (GMA). The remaining protected land consists of bird sanctuaries, game ranches, forest and botanical reserves, and national heritage sites (Mwanza 2006). The Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area (KAZA TFCA), is potentially the world’s largest conservation area, spanning five southern African countries; Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, centred around the Caprivi-Chobe-Victoria Falls area (KAZA 2015). Parks within Zambia that fall under KAZA are: Liuwa Plain, Kafue, Mosi-oa-Tunya and Sioma Ngwezi (Peace Parks Foundation 2013). GCF is dedicated to securing a future for all giraffe populations and (sub)species in the wild. -

African Parks 2 African Parks

African Parks 2 African Parks African Parks is a non-profit conservation organisation that takes on the total responsibility for the rehabilitation and long-term management of national parks in partnership with governments and local communities. By adopting a business approach to conservation, supported by donor funding, we aim to rehabilitate each park making them ecologically, socially and financially sustainable in the long-term. Founded in 2000, African Parks currently has 15 parks under management in nine countries – Benin, Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Zambia. More than 10.5 million hectares are under our protection. We also maintain a strong focus on economic development and poverty alleviation in neighbouring communities, ensuring that they benefit from the park’s existence. Our goal is to manage 20 parks by 2020, and because of the geographic spread and representation of different ecosystems, this will be the largest and the most ecologically diverse portfolio of parks under management by any one organisation across Africa. Black lechwe in Bangweulu Wetlands in Zambia © Lorenz Fischer The Challenge The world’s wild and functioning ecosystems are fundamental to the survival of both people and wildlife. We are in the midst of a global conservation crisis resulting in the catastrophic loss of wildlife and wild places. Protected areas are facing a critical period where the number of well-managed parks is fast declining, and many are simply ‘paper parks’ – they exist on maps but in reality have disappeared. The driving forces of this conservation crisis is the human demand for: 1. -

Detection of Babesia Spp. in Free-Ranging Pukus, Kobus Vardonii, on a Game Ranch in Zambia

ISSN (Print) 0023-4001 ISSN (Online) 1738-0006 Korean J Parasitol Vol. 49, No. 4: 437-440, December 2011 ▣ BRIEF COMMUNICATION http://dx.doi.org/10.3347/kjp.2011.49.4.437 Detection of Babesia spp. in Free-Ranging Pukus, Kobus vardonii, on a Game Ranch in Zambia 1, 2 2 3 Hetron Mweemba Munang’andu *, Musso Munyeme , Andrew Mubila Nambota , King Shimumbo Nalubamba and Victor M. Siamudaala4 1Norwegian School of Veterinary Sciences, Department of Basic Sciences and Aquatic Medicine, Section of Aquatic Medicine and Nutrition, P.O. Box 8146 Dep NO-033, Oslo, Norway; 2Department of Disease Control, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, P.O. Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia; 3Department of Clinical Studies, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, P.O. Box 32379, Lusaka, Zambia; 4Kavango Transfrontier Wild Animal, Gaborone, Botswana Abstract: Babesia spp. were detected from 4 asymptomatic pukus captured on a game ranch in central Zambia in Octo- ber 2008. Blood smears were examined in 4 species of aymptomatic free-ranging antelopes, namely the puku (Kobus vor danii), reedbuck (Redunca arundinum), bushbuck (Tragelaphus sylvaticus), and kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), and showed the presence of Babesia parasites only in the puku. In the puku, the prevalence of babesiosis was estimated at 33.3% (n=12), while the overall prevalence in all examined animals was 8.5% (n=47). The parasites showed morphologi- cal characteristics of paired ring-like stages with the length varying between 1.61 µm and 3.02 µm (mean=2.12 µm, n= 27; SD=0.76 µm). Both the infected and non-infected pukus showed good body condition scores (BCS), while the domi- nant tick species detected from all animals were Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, Rhipicephalus spp., and Boophilus spp. -

Impact Défini

AFRICAN PARKS RAPPORT ANNUEL 2016 IMPACT DÉFINI A vous, hommes et femmes qui mettez vos vies en danger tous les jours pour protéger la faune africaine et les communautés, nous tous à African Parks rendons hommage à votre engagement et saluons vos sacrifices. Couverture: Un ancien de la communauté locale du Parc National de Zakouma, au Tchad. © Brent Stirton Un garde au Parc National de la Garamba, RDC. © Thomas Nicolon African Parks Contenu Message du Président 4 Résumé exécutif du PDG 6 Impact défini 10 Parcs Réserve de Faune de Majete 18 Parc National des Plaines de Liuwa 24 Parc National de la Garamba 30 Zones Humides de Bangweulu 36 Parc National Odzala-Kokoua 42 Parc National de Zakouma 48 Parc National de l’Akagera 54 Ennedi Chinko 60 TCHAD Parc National de Liwonde 66 Parc National Parc National Réserve de Faune de Nkhotakota 72 Pendjari de Zakouma BENIN Parcs en Développement 78 RÉPUBLIQUE Chinko Performances Financières de 2016 80 CENTRAFRICAINE Rapport d’Audit Indépendant 85 Parc National Partenaires Gouvernementaux 86 de la Garamba KENYA Parc National Partenaires Stratégiques 88 Réserve Nationale Odzala-Kokoua RWANDA Organisations et bailleurs individuels 90 RÉPUBLIQUE de Shaba DU CONGO RÉPUBLIQUE Parc Informations institutionnelles 92 DÉMOCRATIQUE African Parks est une organisation sans National de Réserve Nationale Gouvernance 94 but lucratif qui assume la responsabilité DU CONGO l’Akagera directe de la réhabilitation de parcs En commémoration 96 nationaux et d’aires protégées en Zones Humides S’impliquer dans African Parks -

Zambia's Great Migrations

ZAMBIA’S GREAT MIGRATIONS November 5 - 19, 2021 | 14 Days | Small Group Adventure MAP NOT TO SCALE KASANAKA NATIONAL PARK Expedition Highlights SOUTH LUANGWA NATIONAL PARK Mfuwe • Join this brand-new itinerary, ZAMBIA designed and led by renowned wildlife LIUWA photographer and guide, Lex Hes. NATIONAL PARK Lusaka • Witness Africa’s second-largest Sussi & Chuma wildebeest migration in Liuwa Livingstone Lodge National Park. • View the world’s largest mammal migration in Kasanka National Park, To Johannesburg where 10 million straw-colored fruit bats gather each year to feed. • Search for Africa’s highest concentration of leopards in South Luangwa National Park—their rasping calls during night safaris create an otherworldly experience. • Stay at luxurious camps located in prime wildlife-viewing areas. • Itinerary .................................... page 2 > • Flight Information ...................... page 3 > • Meet Your Leader ..................... page 4 > • Rates ........................................ page 4 > VICTORIA FALLS • Know Before You Go ................. page 4 > STRAW-COLORED KING LEWANIKA LODGE FRUIT BATS guided walks to seek out more elusive creatures such as wild Itinerary dogs and honey badgers. This region is also home to more than 300 recorded bird species. Based on the expeditionary nature of our trips, there may be ongoing enhancements to this itinerary. Wednesday, November 10 LIUWA NATIONAL PARK / KASANKA NATIONAL PARK Friday, November 5, 2021 This morning, board our charter flight to Kasanka National DEPART USA Park and check in to your lake-view chalet at Wasa Lodge. Board your independent flight to Zambia. Thursday & Friday, November 11 & 12 Saturday, November 6 KASANKA NATIONAL PARK LUSAKA, ZAMBIA Every year, from October to December, 10 million straw- Arrive in Lusaka and transfer to Latitude 15 Lusaka for colored fruit bats descend on Kasanka in the world’s largest overnight. -

Pendjari African Parks | Annual Report 2017 83

82 THE PARKS | PENDJARI AFRICAN PARKS | ANNUAL REPORT 2017 83 BENIN Pendjari National Park 4,800 km2 African Parks Project since 2017 Government Partner: Government of Benin Government of Benin, National Geographic Society, The Wyss Foundation and The Wildcat Foundation were major funders in 2017 A herd of some of the 1,700 elephants that live within the W-Arly-Pendjari landscape. © Jonas van de Voorde 84 THE PARKS | PENDJARI AFRICAN PARKS | ANNUAL REPORT 2017 85 Pendjari JAMES TERJANIAN | PARK MANAGER BENIN – Pendjari National Park is one of the most recent parks and the first within West Africa to fall under our management. Pendjari which is situated in the northwest of Benin and measures 4,800 km2. It is an anchoring part of the transnational W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) complex, spanning a vast 35,000 km2 across three countries: Benin, Burkina Faso and Niger. It is the biggest remaining intact ecosystem in the whole of West Africa and the last refuge for the region’s largest remaining population of elephant and the critically endangered West African lion, of which fewer than 400 adults remain and 100 of which live in Pendjari. Pendjari is also home to cheetah, various antelope species, buffalo, and more than 460 avian species, and is an important wetland. But this globally important reserve has been facing major threats, including poaching, demographic pressure on surrounding land, and exponential resource erosion. But the Benin Government wanted to change this trajectory and chart a different path for this critically important landscape within their borders. In September 2016, after a visit to Akagera National Park in Rwanda, which has been managed by African Parks since 2016, the Benin Director of Heritage and Tourism (APDT) approached African Parks to explore opportunities to revitalise and protect this landscape, and help the Government realise the tourism potential of Pendjari under their national plan “Revealing Benin”. -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

Zambia – Into the Wild Detailed Itinerary

Zambia – Into the Wild Detailed Itinerary Zambia is a safari enthusiast’s dream with over 30% of the country’s land allocated to National Parks. The wildlife and game are second to none and is a place where you can see rare and endemic sightings of many species including – The Black Lechwe, Shoebill Stork, Sitatunga Antelope and the Blue Duiker. ‘Into the Wild’ itinerary does exactly what it says on the tin; be prepared to wade through boggy swamps to view one of the most rarest storks in the world and horseback ride through herds of Zebra. However we have made sure there is always time to relax and the lodges and places we have suggested to stay ensure you will have an abundance of luxuries. The ‘Africa House’ and ‘Kapishya Hot Springs’ are also a must when planning a trip to Zambia. Our sample itineraries can be modified and adapted to suit your own interests, budget and time; please feel free to design your own itinerary and use this for ideas. Trip Summary 14 days Lodge accommodation Best time to visit: July - November Start LUSAKA > KASANKA NATIONAL PARK > BANGWEULU SWAMPS > SHIWA > NORTH LUANGWA > > end SOUTH LUANGWA Trip Details Day 1-2 Arrive Lusaka International Airport where you will be personally greeted. From the airport we shall travel North by 4x4 safari vehicle to Kasanka National Park, stopping off for lunch along the way, this is a journey of approximately 6 hours. Arrive at the gate of Kasanka National Park where 30k inside the park you will stay on the edges of the majestic Lake Wasa on the Eastern side of the park. -

African Parks Pdf for Web.Indb

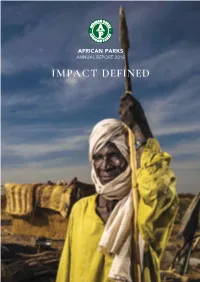

AFRICAN PARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016 IMPACT DEFINED “ To our men and women who put their lives on the line every day to protect Africa’s wildlife and safeguard communities, we at African Parks pay ɯɞȓǤɸɯDZɯɀʗɀɸɞǥɀȳȳȓɯȳDZȶɯLjȶǫȎɀȶɀɸɞʗɀɸɞղɥLjǥɞȓˌȓǥDZɥ.” Cover: A local community elder from Zakouma National Park, Chad. © Brent Stirton A ranger at Garamba National Park, DRC. © Thomas Nicolon ࣉ African Parks Contents Chairman’s Message 4 CEO’s Executive Summary 6 Impact Defined 10 Parks Majete Wildlife Reserve 18 Liuwa Plain National Park 24 Garamba National Park 30 Bangweulu Wetlands 36 Odzala-Kokoua National Park 42 Zakouma National Park 48 Akagera National Park 54 Ennedi Chinko 60 CHAD Liwonde National Park 66 Pendjari Zakouma Nkhotakota Wildlife Reserve 72 National Park National Park BENIN Parks in Development 78 CENTRAL 2016 Financial Performance 80 AFRICAN Chinko REPUBLIC Independent Auditor’s Report 85 Garamba Government Partners 86 National Park KENYA Odzala-Kokoua Strategic Partners 88 Shaba National National Park RWANDA Organisational and Individual Funders 90 CONGO DEMOCRATIC Reserve REPUBLIC OF Institutional Information 92 CONGO Akagera African Parks is a non-profit National ʹΦȉɫʁʜʟɔɷɆʦ Governance 94 organisation that takes on direct Park National Reserve In Remembrance 96 responsibility for the rehabilitation of national parks and protected areas in Bangweulu Get Involved with African Parks 97 partnership with governments and local Wetlands MALAWI communities. We currently have Nkhotakota mandates to manage 10 national parks Wildlife Reserve Liuwa Plain ZAMBIA and protected areas with a combined National Park Liwonde area of six million hectares in seven National Park countries: Bazaruto Majete Wildlife • Chad Archipelago Reserve • Central African Republic (CAR) National Park • The Republic of Congo MOZAMBIQUE • Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) • Rwanda • Malawi • Zambia We are working towards growing our portfolio and increasing the number of parks under management. -

Report:African Parks

REPORT: AFRICAN PARKS Back to the fuTuRe Twenty years ago ecide which tree you’re convinced us we would do better to retreat going to climb – quickly.” than to rush up a tree: my fleeting glimpse of the Majete region of Dorian whispered his her among the tangled mess of branches and Malawi was a barren instructions with a bushes would have to suffice. Despite its “Dpalpable sense of urgency, and with good brevity, my encounter with this increasingly wilderness, its native reason. Climbing trees is apparently the only rare animal, being poached to the edge of animal populations way to escape a charging rhino. extinction, felt a true privilege. About 20m ahead, Shamwari snorted That rhinos are here at all in Majete decimated by poaching. deeply and angrily: her alarm call, warning Wildlife Reserve is thanks to the efforts of us to keep our distance. We’d spent five African Parks, a not-for-profit South African Now, as Sue Watt found, hours since dawn following the tracks of conservation organisation that has been the area is once again black rhinos, trawling across sandy river restoring wildlife to this beautiful corner of beds and grassy slopes, and we’d finally southern Malawi for the past 10 years. In home to elephants, found one obscured by dense thicket, one of Africa’s poorest countries, decades of lions and rhinos, thanks shading itself from the morning sun. poaching and poor policing have taken their According to Dorian Tilbury and his toll, leaving Majete an empty, plundered to the latest pioneering tracking team, Shamwari is a relatively wasteland. -

Private Guided Tours Zambia

Private Guided Tours Zambia. (private Guide South Luangwa Safaris) PRIVATE GUIDED TOURS ZAMBIA IS A TOUR & SAFARI COMPANY FOUND CLOSE TO THE SOUTH LUANGWA NATIONAL PARK. IT WAS FOUNDED IN 2018 BY BORN & BRED LUANGWA VALLEY RESIDENTS. WE OFFER SPECIALIZED SAFARI & TOUR SERVICES TO FLEXIBLE INDEPENDENT TRAVELERS (FIT) AND SMALL GROUPS AROUND ZAMBIA AND SOME OF THE NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES. SERVICES WE OFFER: ❖ PGTZ is dedicated in providing specialized photographic tour and safari services such as; ❖ Game viewing activities in all National Parks around Zambia i.e. South Luangwa ,North Luangwa, Kafue, lower Zambezi, Kasanka etc. ❖ Tours of the Northern circuit for Site seeing, Shoe bill safaris, waterfalls viewing, the spectacular BAT migration in kasanka National Park and for relaxation at Sanfya beach. ❖ Visit of the shiwa house and a warmer swim at kapishya hot spring. WHY BOOK WITH PGTZ • We are local tour operators meaning all revenue directly benefits Zambians. • We offer private photographic safaris with a private tour guide to our Guests. • We ensure sustainable tourism practice. • About 10% of generated sales helps in cooperate social responsibility programs in the community. • Our revenues contributes to rural economic diversification and economic developments. PHOTO GALLERY Some of the exciting photos shared by our esteemed guests. We have a collection of pictures of different mammal species, birds, trees and insects etc. ENDERMIC SPECIES OF ZAMBIA Thornicroft's Giraffe Cookson's wildebeest Kafue Lechwe This is found only in South This is only found in South Kafue Lechwe is only found Luangwa National Luangwa National Park in the Kafue National Park. THE NORTHERN CIRCUIT SPECIALS THE NSAFYA BEACH AT LAKE BANGWEULU THE SHOEBILL STORK THE BATS MIGRATION HAVE FAN AT THE NSAFYA EXPLORE THE SHOEBILL STORKS IN THE WORLD’S BIGGEST MAMMAL BEACH OF LAKE BANGWEULU THE BANGWEULU WETLANDS- MIGRATION IN KASANKA ZAMBIA. -

Tlbw18mar15.Compressed

Dear All My header is a lion - one of three lionesses we saw on a trip through Zambezi National Park, next to Victoria Falls Town, last week. We also saw a honey badger - a very special treat. I had decided that I hadn’t been through the park for many years and, as it was on my doorstep, it was inexcusable. We spent the morning driving along the riverside drive and then in the afternoon ‘did’ Chamabonda Vlei. Highly recommended. LIVINGSTONE Sun International Sells Shares in its company According to an article in the Daily Mail, Sun International has sold shares of its company to a hotel group from Bangkok – Minor International. The Bangkok Group will have a 50% stake in the Falls Resort in Livingstone. The management of the Royal Livingstone and the Zambezi Sun will become a joint venture between Minor and Sun. It will also be involved in Botswana: Gaborone Sun Lesotho: Lesotho Sun and Maseru Sun Swaziland: Royal Swazi, and Ezulwini Sun Namibia: Kalahari Sands This is what Minor International tells us from their website: MINT is a hotel owner, operator and investor with a portfolio of over 14,000 rooms across more than 110 hotels, resorts and serviced suites under the Anantara, AVANI, Per AQUUM, Oaks, Elewana, Four Seasons, Marriott, St. Regis and Minor International brands. Today MINT operates its hotel portfolio in 19 countries, including Thailand, the Maldives, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, Vietnam, Malaysia, China, Tanzania, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Mozambique, Zambia, Lesotho, Swaziland, Botswana, Namibia, Australia and New Zealand. In addition, its mixed-use business operates spas, shopping plazas & entertainment outlets, residential properties, and a points-based vacation club.