Early Automobiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau Und Bootsbau

Karosseriekonzepte und Fahrzeuginterior KFI INSPIRATIONEN DURCH AERODYNAMIK, FLUGZEUGBAU UND BOOTSBAU Dipl.-Ing. Torsten Kanitz Lehrbeauftragter HAW Hamburg WS 2011-12 15.11.2011 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen durch Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau, Bootsbau 1 „Ein fortschrittliches Auto muss auch fortschrittlich aussehen “ Inspirationen durch Raketenbau / Torpedos 1913, Alfa-Romeo Ricotti Eine Vereinigung von Torpedoform und Eiförmigkeit Formale Aspekte im Vordergrund Bildquelle: /1/ S.157 aus: ALLGEMEINE AUTOMOBIL-ZEITUNG Nr.36, 1919 Ein Bemühen, die damaligen Erkenntnisse aus aerodynamischen Versuchen für den Automobilbau 1899 anzuwenden. Camille Jenatzy Schütte-Lanz SL 20, 1917 „Der rote Teufel“ Zunächst: nur optisch im Jamais Contente (Elektroauto) Die 100 km/h Grenze überschritten Bildquelle: /1/ S.45 Geschwindigkeitsrennen waren an der Tagesordnung aus: LA LOCOMOTION AUTOMOBILE, 1899 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen durch Aerodynamik, Flugzeugbau, Bootsbau 2 Inspirationen durch 1906 Raketenbau / Torpedos Daytona Beach „Stanley Rocket “ mit Fred Marriott Geschwindigkeitsweltrekord für Automobile mit Dampfantrieb mit beachtlichen 205,5 km/h Ein Bemühen, die damaligen Erkenntnisse aus aerodynamischen Versuchen für den Automobilbau Elektrotechniker anzuwenden. bedient Schaltungen Zunächst: nur optisch 1902 W.C. Baker Elektromobilfabrik 7-12 PS Elektromotor Torpedoförmiges Fichtenholzgehäuse Bildquelle: /1/ S.63 aus: Zeitschr. d. Mitteleuropäischen Motorwagen-Vereins, 1902 © T. Kanitz 2011 KFI WS 2011/2012 Inspirationen -

29 Annual New London to New Brighton Antique Car Run Saturday

29th Annual New London to New Brighton Antique Car Run Saturday, August 8, 2015 Official Roster & Results 64 started, 53 finished (*denotes first timer) F—Finished DNF—Did not finish 1. Retired in memory of Dick Gold 2. Not Assigned 3. Ed Walhof 1909 REO Spicer, Minnesota F 4. Rob Heyen 1906 Ford Milford, Nebraska F 5. Winston Peterson 1905 REO Golden Valley, Minnesota DNF 6. Peter Fausch 1906 Ford Dayton, Minnesota canceled 7. Floyd Jaehnert 1908 Ford St. Paul, Minnesota F 8. Bill Dubats 1908 Cadillac Coon Rapids, Minnesota F 9. Gene Grengs 1910 Stanley Eau Claire, Wisconsin F 10. Walter Burton 1910 Buick Rice, Minnesota F 11. Jim Laumeyer 1908 Maxwell Rice, Minnesota F 12. Dave Dunlavy 1905 Ford Decorah, Iowa DNF 13. Wade Smith 1905 Columbia San Antonio, Texas F 14. Bruce Van Sloun 1904 Autocar Minnetonka, Minnesota F 15. Gregg Lange 1907 Ford Saginaw, Michigan F 16. Tim Kelly 1906 Ford New Canaan, Connecticut F 17. Mike Maloney 1906 REO Minnetonka, Minnesota F 18. John Biggs 1907 Ford Princes Risborough, England F 19. Rick Lindner 1904 Ford Columbus, Ohio F 20. John Elliott 1912 Maxwell Edina, Minnesota F 21. * Eric Hylen 1908 Maxwell Clearwater, Minnesota F 22. * A. B. Bonds 1908 Buick Kingston Springs, Tennessee DNF 23. Don Ohnstad 1909 Auburn Valley, Nebraska F 24. * Rob Burchill 1909 REO Jefferson, Maryland F 25. David Shadduck 1903 Ford Kildeer, Illinois F 26. * Kimberly Shadduck 1903 Oldsmobile Kildeer, Illinois canceled 27. Alan & Mary Travis 1904 Mitchell Phoenix, Arizona DNS 28. Mark Desch 1905 Stevens-Duryea Stillwater, Minnesota F 29. -

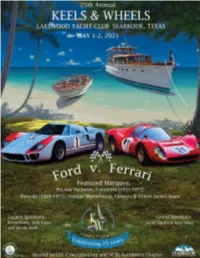

2021 Program

SPONSORS TITLE SPONSOR City of Seabrook LEGACY SPONSORS $50,000 Kevin Brady $10,000 Moody Bank | Tom Koger PLATINUM SPONSORS Bayway Auto Group Evergreen Environmental Services Chesapeake Bay Luxury Senior Living Tony Gullo City of Nassau Bay Meguiar’s Classic Cars of Houston UTMB GOLD SPONSORS Barrett-Jackson Marine Max Yachts Houston Edna Rice, Executive Recruiters McRee Ford Garage Ultimate MSR Houston Generator Exchange Paulea Family Foundation Golf Cars of Houston Ron Carter Clear Lake Cadillac Honda of Houston Star Motor Cars - Aston Martin John Ebeling Technical Automation Services Company Kendra Scott Texas Coast Yachts 6 | Concours d’ Elegance 2021 SPONSORS SILVER SPONSORS Associated Credit Union of Texas Georg Fischer Harvel Beck Design Glacier Pools & Spas Dean & Draper Insurance Company Hagerty Insurance Discover Roofing Hibbs-Hallmark Insurance Dockside Development & Construction LeafGuard Holdings Drilltec Patents & Technologies Co. Pfeiffer & Son Ltd. DriverSource Ranco Industries Frost Bank Reunion Court/12 Oaks - Clear Lake Galati Yacht Sales Shaw Systems Garages of Texas Temperature Solutions Gateway Classic Cars The Delaney at South Shore Geico Insurance Upstream Brokers Generator Supercenter BRONZE SPONSORS Art Jansen Rocking F Ranch - Janet & Dave Foshee Big 4 Erectors Rolli McGinnis Caru West Cargo Containers RV Insurance Solutions LLC John Wilkins South Land Title Lakeside Yachting Center Y.E.S. Yacht Equipment Maudlin & Sons Mfg. Co. Concours d’ Elegance 2021 | 7 CLUB CONCOURS TEXAS MATTRESS MAKERS $1,000 - $2,000 CLUB CONCOURS lub Concours is a new family, or entertain clients. You and unique feature will have exclusive access to the at Keels & Wheels Concours event, upgraded food Concours d’Elegance and beverage service, a private event. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Indiana Automobile History

South Bend: Elkhart: Two dozen makes of The Studebaker cars were manufactured here, La Porte: Company including the popular Elcar. Munson Company produced Mapping the built the first 750,000 cars gasoline-electric from 1901-1963, hybrid cars in america first producing in 1898. electric vehicles. crossroads: Auburn: The Auburn Automobile Company produced cars from 1900 through 1936, including the Indiana first car with front-wheel drive and hidden headlamps; home of the Auburn Cord Automobile Duesenberg Automobile Museum today. History Fort Wayne: The first gasoline pump that could accurately dispense gas was invented by Sylvanus Bowser in 1885, later adding a hose for automobiles. Logansport: The ReVere Motor Car Corporation produced custom handmade automobiles that included the first modern hubcaps. Kokomo: Elwood Haynes built the first Lafayette: successful spark- Subaru of Indiana ignition automobile in Automotive began 1893. Chrysler opened a manufacturing cars factory here in 1956. here in 1989. Muncie: Union City: Home of the Inter-State Automobile Made the Union Company in 1909; Warner Gear (1901) and automobile and later Borg-Warner (1928) manufactured the Le Grande transmissions through 2009. custom bodies. New Castle: Maxwell-Briscoe built the world’s largest automobile factory in 1907, later a Chrysler Plant. Richmond: In 1919 Westcott Motor Car Company introduced bumpers as Indianapolis: standard equipment. Dozens of makes of cars were manufactured here from 1900 Connersville: through the 1930’s. The Cole Eight makes of cars Motor Car Company produced were manufactured the first automobile for a U.S. here, including the President, William Taft in 1910. luxury McFarlan. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway Terre Haute: was built in 1909 as a test site Home of Tony for the new automobile industry. -

Finding Aid for the Collection on Frank Johnson, 1904-1957, Accession

Finding Aid for COLLECTION ON FRANK JOHNSON, 1904-1957 Accession 570 Finding Aid Published: January 2011 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org Updated: 1/10/2011 Collection on Frank Johnson Accession 570 SUMMARY INFORMATION COLLECTOR: Johnson, Russell F. TITLE: Collection on Frank Johnson INCLUSIVE DATES: 1904-1957 BULK DATES: 1904-1942 QUANTITY: 0.8 cubic ft. ABSTRACT: Collected diaries and oral interview transcripts relating to Frank Johnson’s automotive career with Leland and Faulconer, Cadillac Motor Company, Lincoln Motor Company, and Ford Motor Company. ADMINISTRATIVE INFORMATION ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: The papers are open for research ACQUISITION: Donation, 1956 PREFERRED CITATION: Item, folder, box, Accession 570, Collection on Frank Johnson, Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford PROCESSING INFORMATION: Finding aid prepared by Pete Kalinski, April, 2005 2 Collection on Frank Johnson Accession 570 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Russell F. Johnson’s father, Frank Johnson, was born in Paris, Michigan in 1871 and attended local public schools and Michigan State College (now Michigan State University). After earning a degree in mechanical engineering in 1895, Frank Johnson worked as a tool designer and engineer with the Leland and Faulconer Company. Leland and Faulconer Company was a noted machine and tool shop started by Henry M. Leland in 1890 that supplied engines, transmission, and steering gear to the Henry Ford Company and later the Cadillac Motor Company. Leland and his son Wilfred C. Leland assumed control of Cadillac in 1902 and merged the companies. Johnson was instrumental in the key phases of early engine design at Cadillac. -

Download Chapter 119KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 128 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 9 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 129 GEORGE J. HUEBNER 1910–1996 WRITTEN BY JAMES W. FURLONG SUBMITTED BY THE NAE HOME SECRETARY GEORGE J. HUEBNER, JR., one of the foremost engineers in the field of automotive research, was especially noted for developing the first practical gas turbine for a passenger car. He died of pulmonary edema in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on September 4, 1996. George earned a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Michigan in 1932. He began work in the mechanical engineering laboratories at Chrysler Corporation in 1931 and completed his studies on a part- time basis. He was promoted to assistant chief engineer of the Plymouth Division in 1936 and returned to the Central Engineering Division in 1939 to work with Carl Breer, one of the three engineers who had designed the first Chrysler vehicle fifteen years earlier. George was especially pleased to work for Breer, whom he regarded as one of the most capable engineers in the country. Breer established a research office in 1939 and named George as his assistant. It became evident to George that he should bring more science into the field. When he became chief engineer in 1946, he enlarged the activities of Chrysler Research into the fields of physics, metallurgy, and chemistry. He was early to use the electron microscope. George also was early to see the need for digital computers in automotive engineering. Largely in recognition of this pioneering work, he was awarded the Buckendale Prize for computer- Copyright National Academy of Sciences. -

Volume 45 No. 2 2018 $4.00

$4.00 Free to members Volume 45 No. 2 2018 Cars of the Stars National Historic Landmark The Driving Experience Holiday Gift Ideas Cover Story Corporate Members and Sponsors The Model J Dueseberg $5,000 The Model J Duesenberg was introduced at the New York Auto Show December Auburn Gear LLC 1, 1928. The horsepower was rated at 265 and the chassis alone was priced Do it Best Corp. at $8,500. E.L. Cord, the marketing genius he was, reamed of building these automobiles and placing them in the hands of Hollywood celebrities. Cord believed this would generate enough publicity to generate sells. $2,500 • 1931 J-431 Derham Tourster DeKalb Health Therma-Tru Corp. • Originally Cooper was to receive a 1929, J-403 with chassis Number 2425, but a problem with Steel Dynamics, Inc. the engine resulted in a factory switch and engine J403 was replaced by J-431 before it was delivered to Cooper. $1,000 • Only eight of these Toursters were made C&A Tool Engineering, Inc. Gene Davenport Investments • The vehicle still survives and has been restored to its original condition. It is in the collection of the Heritage Museums & Gardens in Sandwich, MA. Hampton Industrial Services, Inc. Joyce Hefty-Covell, State Farm • The instrument panel provided unusual features for the time such as an Insurance altimeter and service warning lights. MacAllister Machinery Company, Inc. Mefford, Weber and Blythe, PC Attorneys at Law Messenger, LLC SCP Limited $500 Auburn Moose Family Center Betz Nursing Home, An American Senior Community Brown & Brown Insurance Agency, Inc. Campbell & Fetter Bank Ceruti’s Catering & Event Planning Gary Cooper and his 1929 Duesenberg J-431 Derham Tourster Farmers & Merchant State Bank Goeglein’s Catering Graphics 3, Inc. -

Download Brochure

F-150 THE ALL-NEW 2021 THE ALL-NEW THE ALL-NEW 2021 ® F-150 ® ® 2021 1 THE ALL-NEW 2021 FORD F-150® TOUGH LEADS TFind the shortest H route to the E front of the packWAY. aboard the toughest, most productive Ford F-150 pickup ever. New technology and productivity features, plus the available new 3.5L PowerBoost® Full Hybrid engine are just the beginning. Top-rank towing and payload numbers are backed by legendary Built Ford Tough® brawn, durability and longevity. And you have great power of choice, with 6 trim levels from the XL to the LIMITED, 6 engines, 3 cabs, 3 box lengths, plus loads of capability and appearance packages. The more you have to do, the more ways the new F-150 can help you get it done. It’s cutting edge, hardworking, and out in front all the way. BEST-IN-CLASS3 BEST-IN-CLASS MAX. AVAILABLE MAX. AVAILABLE 6 L B. - F T. 14,000 LBS. 3,325 LBS. 430 HP 570 TORQUE6 MAX. AVAILABLE TOWING4 MAX. AVAILABLE PAYLOAD5 EXTERIOR DESIGN EXTERIOR LARIAT ™ SUPERCREW® 4x4. Smoked Quartz Metallic Tinted Clearcoat.2 Available Chrome Package. Available equipment. (Max. Payload 2,100 lbs. and Max. Towing 2. Additional charge. 3. Class is Full-Size Pickups under 8,500 lbs. GVWR. 4. Max. towing of 14,000 lbs. available on SuperCab 8' box 4x2 and SuperCrew 4x2 ® 13,900 lbs., when properly equipped with 5.5' box, available 3.5L EcoBoost® engine and available Max. Trailer Tow Package.) configurations with the available 3.5L EcoBoost engine and available Max. -

The London to Brighton Veteran Car Run Sale Veteran Motor Cars and Related Automobilia Friday 31 October 2014

The London To brighTon veTeran car run saLe veteran Motor cars and related automobilia Friday 31 October 2014 The London To brighTon veTeran car run saLe veteran Motor cars and related automobilia Friday 31 October 2014 at 13:30 101 New Bond Street, London viewing bids enquiries cusToMer services Thursday 30 October 14:00 to 16.30 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08.30 to 18:00 Friday 31 October from 09.30 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder saLe TiMes information including after-sale Friday 31 October: We regret that we are unable to Automobilia collection and shipment Automobilia 13:30 accept telephone bids for lots with +44 (0) 8700 273 619 Motor Cars 15:30 a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax Please see back of catalogue Absentee bids will be accepted. [email protected] for important notice to bidders saLe nuMber New bidders must also provide 21903 proof of identity when submitting illusTraTions bids. Failure to do so may result in Front cover: Lot 214 caTaLogue your bids not being processed. Back cover: Lot 222 £25.00 + p&p Live online bidding is available for this sale Please email [email protected] with “Live bidding” in the subject line 48 hours before the auction to register for this service Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams 1793 Ltd Directors Bonhams UK Ltd Directors Registered No. -

Change Your Life in 2007

JACKSONVILLE NING! OPE change your life in 2007 new years resolutions inside freedom writers another oscar for swank? entertaining u newspaper free weekly guide to entertainment and more | january 4-10, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 january 4-10, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents feature New Year’s Resolutions ............................................................PAGES 16-19 Keep Kids Active In 2007 ................................................................ PAGE 20 movies Freedom Writers (movie review) ........................................................ PAGE 6 Movies In Theatres This Week ....................................................PAGES 6-10 Perfume: Story Of A Murderer (movie review) .................................... PAGE 7 Seen, Heard, Noted & Quoted ............................................................ PAGE 7 Happily Never After (movie review) .................................................... PAGE 8 The Reel Tim Massett ........................................................................ PAGE 9 Children Of Men (movie review) ....................................................... PAGE 10 at home The Factotum (DVD review) ............................................................ PAGE 12 Dirt (TV Review) ............................................................................. PAGE 13 Video Games .................................................................................. PAGE 14 Next (book review) ......................................................................... -

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019

The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | April 26 & 27, 2019 The Tupelo Automobile Museum Auction Tupelo, Mississippi | Friday April 26 and Saturday April 27, 2019 10am BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS 580 Madison Avenue Rupert Banner +1 (212) 644 9001 New York, New York 10022 +1 (917) 340 9652 +1 (212) 644 9009 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] 7601 W. Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90046 Evan Ide From April 23 to 29, to reach us at +1 (917) 340 4657 the Tupelo Automobile Museum: 220 San Bruno Avenue [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6514 San Francisco, California 94103 +1 (212) 644 9009 John Neville +1 (917) 206 1625 bonhams.com/tupelo To bid via the internet please visit [email protected] bonhams.com/tupelo PREVIEW & AUCTION LOCATION Eric Minoff The Tupelo Automobile Museum +1 (917) 206-1630 Please see pages 4 to 5 and 223 to 225 for 1 Otis Boulevard [email protected] bidder information including Conditions Tupelo, Mississippi 38804 of Sale, after-sale collection and shipment. Automobilia PREVIEW Toby Wilson AUTOMATED RESULTS SERVICE Thursday April 25 9am - 5pm +44 (0) 8700 273 619 +1 (800) 223 2854 Friday April 26 [email protected] Automobilia 9am - 10am FRONT COVER Motorcars 9am - 6pm General Information Lot 450 Saturday April 27 Gregory Coe Motorcars 9am - 10am +1 (212) 461 6514 BACK COVER [email protected] Lot 465 AUCTION TIMES Friday April 26 Automobilia 10am Gordan Mandich +1 (323) 436 5412 Saturday April 27 Motorcars 10am [email protected] 25593 AUCTION NUMBER: Vehicle Documents Automobilia Lots 1 – 331 Stanley Tam Motorcars Lots 401 – 573 +1 (415) 503 3322 +1 (415) 391 4040 Fax ADMISSION TO PREVIEW AND AUCTION [email protected] Bonhams’ admission fees are listed in the Buyer information section of this catalog on pages 4 and 5.