The Country-Of-Origin Effect in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Do U.S. Consumers Purchase Ethnically Disparate Products?

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2015 Why Do U.S. Consumers Purchase Ethnically Disparate Products? Jong Han Hyun University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Hyun, Jong Han, "Why Do U.S. Consumers Purchase Ethnically Disparate Products?. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2015. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3339 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Jong Han Hyun entitled "Why Do U.S. Consumers Purchase Ethnically Disparate Products?." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Retail, Hospitality, and Tourism Management. Ann E. Fairhurst, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Hee-Jin Lim, Sejin Ha, Stephanie M. Noble Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Why Do U.S. Consumers Purchase Ethnically Disparate Products? A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Jong Han Hyun May 2015 Copyright © 2015 by Jong Han Hyun All rights reserved. -

Writing System Mimicry in the Linguistic Landscape Paul Sutherland [email protected]

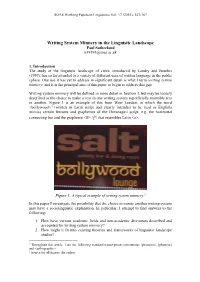

SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics Vol. 17 (2015): 147-167 Writing System Mimicry in the Linguistic Landscape Paul Sutherland [email protected] 1. Introduction The study of the linguistic landscape of cities, introduced by Landry and Bourhis (1997), has so far attended to a variety of different uses of written language in the public sphere. One use it has yet to address in significant detail is what I term writing system mimicry, and it is the principal aim of this paper to begin to address this gap. Writing system mimicry will be defined in more detail in Section 3, but may be loosely described as the choice to make a text in one writing system superficially resemble text in another. Figure 1 is an example of this from West London, in which the word <bollywood> 1 (written in Latin script and clearly intended to be read as English) mimics certain features and graphemes of the Devanagari script, e.g. the horizontal connecting bar and the grapheme <ठ> /ʈʰ/ that resembles Latin <o>. Figure 1: A typical example of writing system mimicry.2 In this paper I investigate the possibility that the choice to mimic another writing system may have a sociolinguistic explanation. In particular, I attempt to find answers to the following: 1. How have various academic fields and non-academic discourses described and accounted for writing system mimicry? 2. How might it fit into existing theories and frameworks of linguistic landscape studies? 1 Throughout this article, I use the following standard transcription conventions: /phonemic/, [phonetic] and <orthographic>. 2 Source for all figures: the author. -

Personal Name Policy: from Theory to Practice

Dysertacje Wydziału Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu 4 Justyna B. Walkowiak Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu Poznań 2016 Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Dysertacje Wydziału Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu 4 Justyna B. Walkowiak Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu Poznań 2016 Projekt okładki: Justyna B. Walkowiak Fotografia na okładce: © http://www.epaveldas.lt Recenzja: dr hab. Witold Maciejewski, prof. Uniwersytetu Humanistycznospołecznego SWPS Copyright by: Justyna B. Walkowiak Wydanie I, Poznań 2016 ISBN 978-83-946017-2-0 *DOI: 10.14746/9788394601720* Wydanie: Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu al. Niepodległości 4, 61-874 Poznań e-mail: [email protected] www.wn.amu.edu.pl Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................ 9 0. Introduction .............................................................................................. 13 0.1. What this book is about ..................................................................... 13 0.1.1. Policies do not equal law ............................................................ 14 0.1.2. Policies are conscious ................................................................. 16 0.1.3. Policies and society ..................................................................... 17 0.2. Language policy vs. name policy ...................................................... 19 0.2.1. Status planning ........................................................................... -

Ethnic Food in the Journey of International College Students in the United States

Research Journal of Foodservice Management & Educaon, Volume 11, Number 1, Pages 23–33 . ©2017 Published jointly by the Foodservice Systems Management Educaonal Council and the Naonal Associaon of Contribuon College & University Food Services Ethnic Food in the Journey of International College Students in the United States Khalid Mahmoud Eyoun, PhD1*; David Spencer Marn, PhD2 1Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA 2Associate Professor, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, USA culture that their restaurant represents. One example of cultural and ABSTRACT ethnic diversity is the success of ethnic food restaurants in the The purpose of this study was to invesgate the importance of ethnic American foodservice market. In 2009, ethnic food sales in the U.S. food to internaonal college students in the U.S. An online survey was surpassed $2.2 billion, and they were expected to increase by 20% by developed through reviewing the relevant literature, conducng focus 2014 (US Ethnic Food Market, 2005). America’s ethnic food market groups, and administering a pilot study. The populaon of this study generates $75 billion in annual sales; almost 65% of this is aributed consisted of internaonal students enrolled in universies across to the restaurant sector of the foodservice industry (US Ethnic Food different regions of the U.S. Four hundred and eleven (411) Market, 2005). quesonnaires were received, 269 of which were usable. This research has discovered that ethnic food is important to internaonal According to Onuorah and Ayo (2003, p. 235), dining habits are students and that the inclusion of ethnic food into on‐campus dining determined by “values, beliefs, and environmental and religious opons is a compeve advantage for universies who provide this circumstances, all of which are products of tradion, culture, and service over those who do not. -

A Multifactorial Sociolinguistic Analysis of Business Naming Practices in Turkey

A MULTIFACTORIAL SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF BUSINESS NAMING PRACTICES IN TURKEY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ALİ FUAD SELVİ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING JULY 2007 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Sencer Ayata Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Prof. Dr. Wolf Konig Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Doç. Dr. Joshua M. Bear Supervisor Examining Committee Members Doç Dr. Joshua M. Bear (METU, FLE) Dr. İsmet Babaoğlu (Doğuş Univ.) Dr. Hasan İnal (Ankara Univ.) iii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name : Ali Fuad Selvi Signature : iv ABSTRACT A MULTIFACTORIAL SOCIOLINGUISTIC ANALYSIS OF BUSINESS NAMING PRACTICES IN TURKEY Selvi, Ali Fuad M.A., Program in English Language Teaching Supervisor : Assoc. Prof. Dr. Joshua M. Bear July 2007, 169 pages The growing world supremacy of English and its relentless spread across the globe is both widely criticized for becoming a ‘threat’ and causing socio-cultural destruction in the form of linguistic imperialism and appreciated for being a ‘basic survival skill’ and a global commodity to which every individual adds a distinct flavor and which has crucial pragmatic and instrumental functions, benefits and prestige for its users. -

Chapter 11 Floating Ideologies: Metamorphoses of Graphic “Germanness”

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2012 Floating ideologies: Metamorphoses of graphic ,Germanness‘ Spitzmüller, Jürgen DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614511038.255 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-25191 Book Section Published Version Originally published at: Spitzmüller, Jürgen (2012). Floating ideologies: Metamorphoses of graphic ,Germanness‘. In: Jaffe, Alexandra; Androutsopoulos, Jannis; Sebba, Mark; Johnson, Sally. Orthography as Social Action: Scripts, Spelling, Identity and Power. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 255-288. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/9781614511038.255 Chapter 11 Floating ideologies: Metamorphoses of graphic “Germanness” J¨urgen Spitzm¨uller 1. Introduction After decades of almost exclusive focusing on spoken language, a growing interest in written communication and scriptal variation can be noticed in sociolinguistics recently (cf. Jaffe 2000; Johnson 2005; Androutsopoulos 2007; Sebba 2007; this volume). This interest, however, is still in many ways limited. It is limited quantitatively, in that only a few scholars systematically explore the sociolinguistic relevance of scriptal variation at all (cf. Sebba 2009 for a recent overview), and it is limited qualitatively insofar as the existing studies focus only on a small range of scriptal variation, particularly on orthography and spelling. Other aspects of scriptality (such as typography) are virtually unexplored sociolinguistically. A “sociolinguistics of writing” (Androutsopoulos 2007: 86) thus still has a long way to go even to find out how large the field it attempts to explore actually is. The existing research on writing and its use (cf. -

An Investigation of the Importance of Ethnic Food to International College Students in The

An Investigation of the Importance of Ethnic Food to International College Students in the United States by Khalid Mahmoud Eyoun A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama August 3, 2013 Keywords: Internationalization of Education, Importance of International Students, Recruitment, Acculturation, Ethnic Food Copyright 2013 by Khalid Mahmoud Eyoun Approved by David Martin, Chair, Assistant Professor of Nutrition, Dietetics, and Hospitality Management Martin O’Neill, Professor & Department Head Department of Nutrition, Dietetics & Hospitality James Witte, Professor of Educational Foundations, Leadership & Technology i Abstract This study is aimed at investigating the importance of ethnic food to international college students in the U.S. Specifically, this research seeks to investigate the effect of the inclusion of ethnic food into on-campus dining options and the future behavioral intentions and self-reported personal health of international students. Additionally, this research identifies the reasons underlying the importance attached to ethnic food, examines the current perceptions about the availability and quality of ethnic food restaurants and retailers, and identifies the ethnic food dining habits of international students. Due to the lack of previous research in this area, both qualitative and quantitative approaches are necessary in this study to establish a foundation that can be used in future research within this area. This study employs t-test and descriptive statistics to answer the research questions. Overall, this research has discovered that ethnic food is important to international students and that the inclusion of ethnic food into on-campus dining options is a competitive advantage for universities who provide this service over those who do not. -

Nation Branding a Brand New Marketing Tool on the Global Arena

STOCKHOLM SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS Department of Marketing and Strategy Bachelor Thesis, Spring 2012 Nation Branding A Brand New Marketing Tool on the Global Arena A Qualitative Case Study in a Swedish Context Abstract: Global competition is becoming fierce. New marketing techniques are emerging, among them Nation Branding. The aim of this study is to answer the following questions: What is Nation Branding and how is it applied in Sweden? Why is Nation Branding controversial and when does it matter? The study is performed through a qualitative, abductive approach. The empirical data is compared with theory by applying conventional marketing theory as well as corporate co-branding theory and cultural branding. Recently developed Nation Branding theories, such as the Nation Brand Hexagon and Index (NBI) and the Nation Brand Architecture model (NBAR), are used together with a Public Diplomacy framework in this research. This also opens up for a hermeneutic, holistic perspective including export related Heckscher-Ohlin framework. The primary data consists of interviews with practitioners and the general public. The secondary data are a literature research and a study of the NSU organs and stakeholders: The Swedish Institute, Visit Sweden, the Trade Council and Invest Sweden’s web-pages. The findings of this paper are that: Sweden is a nation with a long tradition of Nation Branding. According to practitioners and general public, Sweden is successful in its Nation Branding activities, distributing a “relevant picture” of Sweden, stimulating branded exports, and portraying Sweden as being a trustworthy, environmentally friendly and innovative nation. Moreover, Sweden scores well in the NBI, with a positive impact on both people working with Nation Branding in Sweden, as well as among the public. -

The Effect of Perceived Country of Origin on Brand Attitude, Brand Trust and Purchase Intentions

The Effect of Perceived Country of Origin on Brand Attitude, Brand Trust and Purchase Intentions Master Thesis Student: Mariya Petrova Student Number: 10993150 Date of submission: 29.01.2016 Supervisors: Drs. ing. A.C.J. Meulemans Drs. F. Slisser Program: MSc. in Business Administration – Marketing Track University of Amsterdam Statement of originality This document is written by Mariya Petrova who declares to take full responsibility for the contents of this document. I declare that the text and the work presented in this document are original and that no sources other than those mentioned in the text and its references have been used in creating it. The Faculty of Economics and Business is responsible solely for the supervision of completion of the work, not for the contents. 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Drs. Meulemans for his time, guidance, expert advice and feedback throughout the process of writing this thesis. Furthermore, I would like to express my gratitude to all of the participants in my survey whose responses provided valuable insights and helped me conduct this research. Lastly, I am grateful to my friends and family for their immense support and involvement. 3 Abstract Recent research suggests that the country of origin effect is present regardless of consumers’ knowledge of the actual country of brand origin. Thus the concept of perceived country of origin emerged. The purpose of this thesis is to explore the effect of perceived country of origin on brand attitude, brand trust and purchase intentions. An online survey was conducted to answer the question to what extent the perception of a favorable country of origin, regardless of the actual country of brand origin, results in a positive effect on consumers’ attitude, trust and purchase intentions towards the brand. -

2.2 Consumer Culture Positioning in Advertising

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit “Consumer Culture Positioning in Advertising and Ad- Brand Incongruity Does It Impact Brand Perceptions?” Verfasserin Christine Milchram, B.A. angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Science (MSc) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 914 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Internationale Betriebswirtschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. DDr. Adamantios Diamantopoulos Ich versichere, 1. dass ich diese Masterarbeit selbstständig verfasst, keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel benutzt und mich auch sonst keiner unerlaubten Hilfe bedient habe, 2. dass ich diese Masterarbeit bisher weder im In- oder Ausland in irgendeiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt habe, Wien, im August 2012 _______________________________ II With special thanks to: Univ.-Prof. DDr. Adamantios Diamantopoulos and the team at the Chair of International Marketing for providing me with the skills and opportunity to write the thesis at the Chair of International Marketing and their valuable insight Dipl.-Kffr. Birgit Löhndorf for her commitment in mentoring the thesis, her time and continuous support at every step of the project and extensive feedback My family and friends for motivating me and for proof-reading; especially my sister Maria Milchram for her patient and detailed corrections of my writing Dr. Amata Ring and Dr. Nils Löhndorf for their support with the pretest data collection everybody who helped me with the data collection and took part in the surveys for their time and support in providing the data upon which this thesis is built III Abstract This thesis examines the effect of consumer culture positioning and ad-brand incongruity in print advertisements on consumers’ brand perceptions. Local, foreign or global consumer culture positioning creates links between a brand and a specific local, foreign or global consumer culture. -

The Center for English As a Lingua Franca Journal 玉川大学

2017 April Volume 3 ISSN 2189-0463 ELF The Center for English as a Lingua Franca Journal 玉川大学 Enhancing Intelligibility in ELF by Focusing on the Origin of Katakana Loanwords Classroom-based Strategies on Improving Speaking and Listening Skills through the Voices of Japanese Learners Pedagogical Concerns and Approaches to EAP Writing Instruction within an ELF Program A Brief Catalogue and Review of Key Online Video Resources and Platforms Self-directed Learning for English Language Learners Fostering Students to State Opinions Comfortably through a Speaking Activity Computer-assisted Language Tests for the English Classroom: Blackboard® Tests and Google Forms New Learning and Teaching Modalities: The Reinvented Learning Spaces at ELF Study Hall 2015, Tamagawa University M-Reader in the Center for English as a Lingua Franca Report of the Center for English as a Lingua Franca Tutor Service CONTENTS A Report on Faculty Development and Research at the Center for English as a Lingua Franca The Center for ELF Journal Issue Editors: Brett Milliner, Travis Cote and Blagoja Dimoski Assistant Editor: Andrew Leichsenring Translation: Mitsuko Imai Reviewers: Ethel Ogane Mitsuko Imai Jesse Hsu Rasami Chaikul Paul McBride Yuri Jody Yujobo Yoji Kudo Jeremy White Daniel Worden Ayako Suzuki Simeon Flowers Michael Seko Angelo Magasic The Center for ELF Journal: Call for Articles descriptions of research method including clear demonstration of attention to research ethics and commentary. The Center for ELF Journal is a refereed journal that seeks to promote critical re- flection among English language teaching professionals from a wide range of profes- Teaching articles: Teaching articles should provide a description of the teaching sional contexts. -

Muoto Ennen Sisältöä

Muoto ennen sis¨alt¨o¨a Tuomas Korppi 22. syyskuuta 2021 Sis¨alt¨o I Genreitt¨ain 3 Scifiraapaleita . 4 Kauhuraapaleita . 109 Fantasiaraapaleita . 276 Mainstream-raapaleita . 357 II Raapalesarjoja 617 Raapalev¨aritrilogia . 618 Riivaaja . 620 Kafil, ainoa olemassaoleva jumala . 624 Lohik¨a¨armeen Valtakunta . 633 Kaisa . 640 Kukkahattup¨ainen t¨ati . 652 Yksityisetsiv¨a Achille Pursot . 655 Hullu Tiedemies . 661 Ydinperhe . 669 Taikuri Merkuriuksen taikakauppa . 677 Johan ja Mirva . 683 Koronaraapaleita . 692 Tiedesjumala . 700 1 III Tekstiviestitarinoita 704 Tekstiviestitarinoita aikuisille . 705 Tekstiviestitarinoita lapsenmielisille . 714 2 Osa I Genreitt¨ain 3 Scifiraapaleita Identiteettikriisi Pekka vihasi massaan sulautumista. Tietokoneeltaan (Coca-Cola) h¨an oli huomannut, ett¨a kolmella Maapallon kymmenest¨a miljardis- ta asukkaasta oli samat kulutustottumukset kuin h¨anell¨a. Ihmisell¨a on parikymment¨a tarvetta ja jokaista tyydytt¨am¨ass¨a tuote jokaisel- ta viidest¨a korporaatiosta. Kombinatorinen r¨aj¨ahdys takaa jokaisel- le maapallon asukkaalle mahdollisuuden yksil¨olliseen identiteettiin kulutustottumusten avulla. Vaihtoehtoja on 520 eli 95367431640625. Nyt jotkut kusip¨a¨at j¨aljitteliv¨at Pekkaa. H¨anen t¨aytyisi muuttaa tottumuksiaan. Tietokoneellaan h¨an tutki eri vaihtoehtoja: Tulisiko vaihtaa Microsoftin hampurilainen McDonaldsiin vai Pepsin stereo- laitteisto Sonyyn? Hampurilaisen vaihto ei kannattaisi, k¨ayttih¨an h¨an yhdeks¨a¨a McDonaldsin tuotetta. Useat k¨ayttiv¨at montaa sa- man yhti¨on tuotetta, joten uusi kulutustottumuksien vaihto oli- si todenn¨ak¨oinen. Pekka p¨a¨atti vaihtaa Sonyn aamiaismuroihin. Eiv¨ath¨an tuotteiden maut eronneet. Tauhkaa Petteri sai huolestuttavan viestin. Mink¨a h¨anen genomissaan piti olla tauhkaa, olikin omisteista. 4 Kun tietotekniikka ja geenimuuntelu olivat vallanneet maailman, sill¨a oli odottamaton sivuvaikutus: Asiat, jotka ennen olivat olleet elottomia, olivat nyt t¨aynn¨a intentioita.