Draft 3.02.17 1 Downtown Waterfront District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Heart of Boston Stunning Waterfront Location

IN THE HEART OF BOSTON STUNNING WATERFRONT LOCATION OWNED BY CSREFI INDEPENDENCE WHARF BOSTON INC. independence wharf 470 atlantic avenue • Boston, MA Combining a Financial District address with a waterfront location and unparalleled harbor views, Independence Wharf offers tenants statement-making, first-class office space in a landmark property in downtown Boston. The property is institutionally owned by CSREFI INDEPENDENCE WHARF BOSTON INC., a Delaware Corporation, which is wholly owned by the Credit Suisse Real Estate Fund International. Designed to take advantage of its unique location on the historic Fort Point Channel, the building has extremely generous window lines that provide tenants with breathtaking water and sky line views and spaces flooded with natural light. Independence Wharf’s inviting entrance connects to the Harborwalk, a publicly accessible wharf and walkway that provides easy pedestrian access to the harbor and all its attractions and amenities. Amenities abound inside the building as well, including “Best of Class” property management services, on-site conference center and public function space, on-site parking, state-of-the-art technical capabilities, and a top-notch valet service. OM R R C AR URPHY o HE R C N HI IS CI ASNEY el CT ST v LL R TI AL ST CT L De ST ESTO ST THAT CHER AY N N. ST WY Thomas P. O’Neill CA NORTH END CLAR ST BENN K NA ST E Union Wharf L T Federal Building CAUSEW N N WASH ET D ST MA LY P I ST C T NN RG FR O IE T IN T ND ST ST S FL IN PR PO ST T EE IN T RT GT CE ST LAND ST P ON OPER ST ST CO -

Human Longing Is for Nothing Less Than the Reconciliation of Time and Place

uman longing is for nothing less than the reconciliation of time and place, of past and future, of the many and the one, of the living and the dead. HBoston is precious because it lives in the national imagination, and increasingly the world’s, just so— as a still brilliant map of America’s good hope. —James Carroll from Mapping Boston Helping to Build The Good City The Boston Foundation works closely with its donors to make real, measurable change in some of the most important issues of our day. A number of key areas of community life benefited from the Foundation’s “Understanding Boston” model for social change in 2005: Research This year, the Foundation’s third biennial Boston Indicators Report identified the key competitive issues facing Boston and the region and offered an emerging civic agenda. The Foundation also released the third annual “Housing Report Card” and a report on ways for towns and cities to build affordable housing without increasing school costs. Other reports focused on goals for Boston Harbor and the Waterfront—and the impact and role of Greater Boston’s higher education institutions through the Carol R. Goldberg Seminar. Major Convenings All Boston Foundation reports are released at forums attracting thousands of people every year. In 2005 alone, the Foundation held some 20 forums on a diverse set of issues—including two major housing convenings, sessions focused on strengthening the nonprofit sector and community safety—and forums examining the effects of the tsunami and Hurricane Katrina on national and local philanthropy. Task Forces Task Forces of experts and stakeholders are convened and facilitated by the Foundation. -

Pg. 1 Downtown Waterfront Municipal Harbor Planning Advisory

Downtown Waterfront Municipal Harbor Planning Advisory Committee Meeting No. 34 Wednesday, May 11, 2016 Boston City Hall, Piemonte Room Attendees Advisory Committee (“Committee”): Bruce Berman, Marianne Connolly, Joanne Hayes-Rines, Jill Valdes Horwood, Lee Kozol, Eric Krauss, Susanne Lavoie, Bud Ris, Meredith Rosenberg, Lois Siegelman, Greg Vasil, Robert Venuti City of Boston (“City”): Richard McGuinness, Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA); Lauren Shurtleff, BRA; Chris Busch, BRA; Erikk Hokenson, BRA Consultant Team: Matthew Littell, Utile; Tom Skinner, Durand & Anastas; Craig Seymour, RKG Associates Government Representatives: Lisa Engler, Office of Coastal Zone Management (CZM); Sue Kim, Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) Members of the Public: M. Barron, J. Berman, Jane Berman, Victor Brogna, Valerie Burns, Don Chiofaro, Duna Chiofaro, Steven Comen, Steve Dahill, Chris Fincham, Julie Hatfield, Donna Hazard, Mary Holland, Dorothy Keville, Tony Lacasse, Todd Lee, Julie Mairaw, Arlene Meisner, Norman Meisner, Sy Mintz, Thomas Nally, Frank Nasisi, Charles Norris, Tom Palmer, Chris Regnier, Erik Rexford, Laura Rood, Diane Rubin, Bob Ryan, Patricia Sabbey, Wes Stimpson, David Weaver, Heidi Wolf, Barbara Yonke, Parnia Zahedi, Bill Zielinski Meeting Summary Mr. Richard McGuinness, BRA, opened the meeting at 3:05 PM by introducing BRA staff and the consultant team. Mr. McGuinness informed the Committee that as Ms. Sydney Asbury, Chair of the Committee, is expected to give birth in the coming days, she would not be attending today’s meeting. In addition, Mr. Tom Wooters, MHPAC Member, passed away a number of weeks ago. Mr. Lee Kozol, Harbor Towers, was appointed to replace him on the Committee as a representative of Harbor Towers. Mr. McGuinness also drew the Committee’s attention to the upcoming schedule of meetings on the back of the agenda; the schedule includes two night meetings – June 22 and July 20 from 6 – 8 PM – at the public’s request. -

Boston Harbor National Park Service Sites Alternative Transportation Systems Evaluation Report

U.S. Department of Transportation Boston Harbor National Park Service Research and Special Programs Sites Alternative Transportation Administration Systems Evaluation Report Final Report Prepared for: National Park Service Boston, Massachusetts Northeast Region Prepared by: John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Cambridge, Massachusetts in association with Cambridge Systematics, Inc. Norris and Norris Architects Childs Engineering EG&G June 2001 Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

State of the Park Report, Salem Maritime National Historic Site

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior STATE OF THE PARK REPORT Salem Maritime National Historic Site Salem, Massachusetts April 2013 National Park Service 2013 State of the Park Report for Salem Maritime National Historic Site State of the Park Series No. 7. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: The tall ship, Friendship of Salem, the Custom House, Hawkes House, and historic wharves at Salem Maritime Na- tional Historic Site. (NPS) Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infra- structure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non-quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. SALEM MARITIME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 State of the Park Summary Table 3 Summary of Stewardship Activities and Key Accomplishments to Maintain or Improve Priority Resource Condition: 5 Key Issues and Challenges for Consideration in Management Planning 6 Chapter 1. -

Inner Harbor Connector Ferry

Inner Harbor Connector Ferry Business Plan for New Water Transportation Service 1 2 Inner Harbor Connector Contents The Inner Harbor Connector 3 Overview 4 Why Ferries 5 Ferries Today 7 Existing Conditions 7 Best Practices 10 Comprehensive Study Process 13 Collecting Ideas 13 Forecasting Ridership 14 Narrowing the Dock List 15 Selecting Routes 16 Dock Locations and Conditions 19 Long Wharf North and Central (Downtown/North End) 21 Lewis Mall (East Boston) 23 Navy Yard Pier 4 (Charlestown) 25 Fan Pier (Seaport) 27 Dock Improvement Recommendations 31 Long Wharf North and Central (Downtown/North End) 33 Lewis Mall (East Boston) 34 Navy Yard Pier 4 (Charlestown) 35 Fan Pier (Seaport) 36 Route Configuration and Schedule 39 Vessel Recommendations 41 Vessel Design and Power 41 Cost Estimates 42 Zero Emissions Alternative 43 Ridership and Fares 45 Multi-modal Sensitivity 47 Finances 51 Overview 51 Pro Forma 52 Assumptions 53 Funding Opportunities 55 Emissions Impact 59 Implementation 63 Appendix 65 1 Proposed route of the Inner Harbor Connector ferry 2 Inner Harbor Connector The Inner Harbor Connector Authority (MBTA) ferry service between Charlestown and Long Wharf, it should be noted that the plans do not specify There is an opportunity to expand the existing or require that the new service be operated by a state entity. ferry service between Charlestown and downtown Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) Boston to also serve East Boston and the South and the Massachusetts Port Authority (Massport) were Boston Seaport and connect multiple vibrant both among the funders of this study and hope to work in neighborhoods around Boston Harbor. -

PEABODY SQUARE Ashmont

The Clock in PEABODY SQUARE Ashmont On the occasion of the Welcome Home Ceremony, May 31, 2003, for the newly restored Monument Clock in Peabody Square, Dorchester Foreword The celebration of the re-installation of the Peabody Square Clock offers an opportunity to reflect on Dorchester’s history. Through the story of the clock — how it came to be here, how the park in which it stands was created, how it was manufactured, how it has stood for decades telling the hours as Dorchester life con- tinues — we can see the story of our communi- ty. The clock, like many features of the urban landscape that have stood for many years, has become a part of the place in which we live. A sense of place, our place, helps to ground our thoughts, to provide a starting point for where we are going. Our community’s history can inspire us by providing a perspective on the course of our own lives. Recognizing and embracing and caring for the symbols of our place can reward us; these symbols can inform and educate and entertain. They make Dorchester Dorchester. Acknowledgements We thank the City of Boston and Mayor Thomas M. Menino for seeing this important project through. We appreciate the City’s commitment and the support of the Edward Ingersoll Browne Fund and the City’s Neighborhood Improvements through Capital Expenditures (N.I.C.E.) Program. Several individuals who worked on the project deserve special mention for their unstinting efforts over the course of many months. 1. John Dalzell who coordinated the process from the city’s end; 2. -

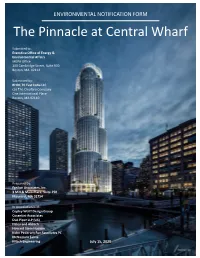

Mepa Environmental Notification Form

ENVIRONMENTAL NOTIFICATION FORM The Pinnacle at Central Wharf Submitted to: Executive Office of Energy & Environmental Affairs MEPA Office 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02114 Submitted by: RHDC 70 East India LLC c/o The Chiofaro Company One International Place Boston, MA 02110 Prepared by: Epsilon Associates, Inc. 3 Mill & Main Place, Suite 250 Maynard, MA 01754 In Association with: Copley Wolff Design Group Cosentini Associates DLA Piper LLP (US) Haley and Aldrich Howard Stein Hudson Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates PC McNamara Salvia Nitsch Engineering July 15, 2020 July 15, 2020 PRINCIPALS Subject: The Pinnacle at Central Wharf Theodore A Barten, PE Environmental Notification Form Margaret B Briggs Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Dale T Raczynski, PE Cindy Schlessinger Dear Interested Party: Lester B Smith, Jr Robert D O’Neal, CCM, INCE On behalf of the Proponent, RHDC 70 East India LLC, I am pleased to send you the Michael D Howard, PWS enclosed Environmental Notification Form (ENF) for the redevelopment of the 1.32-acre Douglas J Kelleher Boston Harbor Garage site in Boston’s Downtown Waterfront District. The project is AJ Jablonowski, PE located at 70 East India Row (a/k/a 270 Atlantic Avenue) in the City of Boston. Stephen H Slocomb, PE The Proponent expects that the ENF will be noticed in the Environmental Monitor on July David E Hewett, LEED AP 22, 2020 and that comments will be due by August 11, 2020. Comments can be submitted Dwight R Dunk, LPD online at: David C Klinch, PWS, PMP Maria B Hartnett https://eeaonline.eea.state.ma.us/EEA/PublicComment/Landing/ or sent to: ASSOCIATES Secretary Kathleen A. -

Boston Nps Map A5282872-8D05

t t E S S G t t B S B d u t D t a n n I S r S r k t l t e e R North S l o r e s To 95 t e o t c H B l o t m i t S m t S n l f b t t n l a le h S S u S u R t c o o t s a S n t E n S C T a R m n t o g V e u l S I s U D e M n n R l s E t M i e o F B V o e T p r s S n x e in t t P p s u r e l h H i L m e r u S C IE G o a S i u I C h u q e L t n n r R E L P H r r u n o T a i el a t S S k e S 1 R S w t gh C r S re t t 0 R 0 0.1 Kilometer 0.3 F t S t e M S Y a n t O r r E e M d u M k t t T R Phipps n S a S S e r H H l c i t Bunker Hill em a Forge Shop V D e l n t C o i o d S nt ll I 0 0.1 Mile 0.3 Street o o Monument S w h o n t e P R c e P S p Cemetery S W e M t IE S o M r o e R Bunker Hill t r t n o v C A t u R A s G S m t s y 9 C S h p a V e t q e t Community u n V I e e s E W THOMPSON S a t W 1 r e e s c y T s College e t r t e SQUARE i S v n n n d t Gate 4 t o S S P r A u w Y n S W t o i IE t a t n t o a lla L e R W c 5 S s t n e Boston Marine Society M C C S t i y n e t t o 8 r a a y h a r t e f e e e m t S L in t re l l A S o S S u C t S a em n P m o d t Massachusetts f h t w S S n a 1 i COMMUNITY u o t m S p r n S s h b e Commandant’s Korean War o M S i u COLLEGE t n t S t p S O S t b il c M TRAIN ING FIELD House Veterans Memorial d R l e D u d i n C R il n ti W p P t d s R o o S Y g u a u m u d USS Constitution i A sh t M r o D n W O in on h t th m t o SHIPYARD g g i er s S a n n lw Museum O P a M n i o a l W t U f n t n i E C PARK y B O Ly o o e n IE s n r v S t m D K a n H W d R N d e S S R y 2 S e t 2 a t 7 s R IG D t Y r Building -

TENTACLES TAKE HOLD at the NEW ENGLAND AQUARIUM +300 MORE THINGS to DO in BOSTON RIGHT NOW! Bostonguide.Com OYSTER PERPETUAL YACHT-MASTER II

July 4–17, 2016 THE OFFICIAL GUIDE TO BOSTON PANORAMAEVENTS | SIGHTS | SHOPPING | MAPS | DINING | NIGHTLIFE | CULTURE TENTACLES TAKE HOLD at the NEW ENGLAND AQUARIUM +300 MORE THINGS TO DO IN BOSTON RIGHT NOW! bostonguide.com OYSTER PERPETUAL YACHT-MASTER II rolex oyster perpetual and yacht-master are ® trademarks. July 4–17, 2016 THE OFFICIAL GUIDE TO BOSTON Volume 66 • No. 4 contents Features Pops Stars 6 Singing sensations Nick Jonas and Demi Lovato join the annual Boston Pops Fireworks Spectacular PANO’s Guide to 8 Outdoor Dining Enjoy prime patio season at these top spots for al fresco fare 6 Departments 10 Boston’s Official Guide 10 Multilingual 15 Current Events 21 On Exhibit 24 Shopping 27 Cambridge 30 Maps 36 Neighborhoods 8 40 Real Estate 42 Sightseeing 48 Beyond Boston 50 Freedom Trail 52 Dining 62 Boston Accent Aquarist Bill Murphy of the New England Aquarium ON THE COVER: The giant Pacific octopus at the New England Aquarium (refer to listing, page 47). 62 PHOTOS (TOP TO BOTTOM): NICK JONAS AND DEMI LOVATO COURTESY OF THE BOSTON POPS; LEGAL HARBORSIDE BY CHIP NESTOR; COURTESY OF NEW ENGLAND AQUARIUM BOSTONGUIDE.COM 3 THE OFFICIAL GUIDE TO BOSTON bostonguide.com SPECTACULAR VIEWS July 4–17, 2016 Volume 66 • Number 4 Tim Montgomery • Publisher Scott Roberto • Art Director/Acting Editor Laura Jarvis • Assistant Art Director EXQUISITE CUISINE Andrea Renaud • Senior Account Executive Olivia J. Kiers • Editorial Assistant Keren Osuji, Shannon Nicole Steffen Editorial Interns UNSURPASSED SERVICE At this Tim Montgomery • President & CEO Boston takes Tyler J. Montgomery • Vice President, Operations on a beauty Rita A. -

Boston Market Report Table of Contents

2019 YEAR END BOSTON MARKET REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 2020 and Beyond: Boston’s Condo Market Forecast . 4 BOSTON CITYWIDE Overview . 6 Sales Price By Range . 7 Bedroom Growth . 8 The Leaderboard 2019 . 9 Pipeline . .. 10 BOSTON SUBMARKETS Allston/Brighton . 12 Back Bay . 14 Beacon Hill . 16 Charlestown . 18 East Boston . 20 The Fenway . 22 Jamaica Plain . 24 Midtown . 26 North End . 28 Seaport/Fort Point . 30 South Boston . 32 South End . 34 Waterfront . 36 GREATER BOSTON AREA SUBMARKETS Brookline . 38 Cambridge . 39 Note: Dorchester, Roxbury, Mattapan, Hyde Park, Mission Hill, Roslindale, and West Roxbury were not included in the submarket segment of this report. Condo sales in these neighborhoods were included in the Boston Citywide subsection. 2019 AT A GLANCE developments, 100 Shawmut and The Quinn . of Boston’s primary submarkets, especially in 2020 Looking at East Boston, another supply the South End with closings at 100 Shawmut 2019 was a landmark year in Boston’s condo constrained neighborhood with 2 .4 months and The Quinn, and in the Fenway with 60 market as a wave of new luxury construction AND of supply, there has been tremendous price Kilmarnock . In late 2021, the Residences at St. projects throughout the city begin to close . growth in the past two years, driven primarily Regis and the condominiums in the new Raffles Just as the closings at Millennium Tower did by sales along hotel will continue to push for new highs at the in 2016, Pier 4, One Dalton, and Echelon BEYOND the waterfront top end of the market in the Seaport and Back sales pushed 2019 sales prices and price per at The Mark at Bay . -

Custom House Tower

Custom House Tower Located in the National Register of Historic Places - Custom House District, the original neoclassical- designed Boston Custom House building was completed in 1844 and the clock tower later completed in 1915. This National Historic Landmark was the tallest building in Boston until 1964. 3 McKinley Square Financial District Boston, MA Architectural Features Neo-Classical Design < Original Base Structure > Cruciform (cross) Shaped Greek Doric Patio & Roman Dome 36 Fluted Doric Granite Columns Each Column - Single Piece of Granite Columns 32’ high | 5’ Diameter Top Portion of Building 26th Floor | Observation Deck Tower Clock | 22’ Diameter | 4 Faces Building Use and Transition Developed at Base of City Docks (prior to land reclamation) Location Facilitated Cargo Registration & Inspection Conversion to 80 Room Hotel Marriott Custom House PROJECT SUMMARY Project Description A Neo-Classical designed architectural and historic landmark comprised of a 3-story cruciform (cross) shape building with a Greek Doric portico, Roman dome and 36 fluted Doric columns, each carved from a single piece of granite from nearby Quincy, Massachusetts. The building was positioned at the base of the shipping docks, prior to land reclamation in the Boston seaport area. The 32 story, 356’ Custom House Clock Tower was later completed between 1913 - 1915 and was the tallest building in Boston until 1964. Official Building Name Custom House Tower Marriott Custom House (2016) Other Building Names Boston Custom House U.S. Custom House Location Boston Custom House District | National Register of Historic Places 3 McKinley Square, Boston, MA in Boston’s Financial District Bordered by McKinley Square, State Street, India Street & Central Street Original Custom House Site Purchased - 1837 | Completion - 1847 Clock Tower Start - 1913 | Completion - 1915 History Custom House original use - shipping inspection & registration Federally owned until 1987 Custom House Tower - Tallest building in Boston 1915 to 1964 LEADERSHIP | OWNERSHIP | PROJECT DESIGN U.S.