Ernest Mandel the Meaning of the Second World War Ernest Mandel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Azerbaijan in the Victory Over Fascism

A-PDFProperty Split DEMO of : Purchasehistory from www.A-PDF.com to remove the watermark Zumrud HASANOVA The Role of Azerbaijan in the Victory over Fascism THis Year HUMANitY is celeBratiNG THat it is 65 Years siNce THE END of THE SecoND World War, KNowN IN THE forMer Soviet UNioN as THE Great Patriotic War. THE FUrtHer froM OUR tiME THE UNforGettaBle date 9 MaY 1945 is reMoved THE GraNder THE GIGANtic feat of THE victors over fascisM appears to MANkiND. 28 www.irs-az.com 1 2 3 4 1. Hazi Aslanov – Guard commander, major general, twice Hero of the Soviet Union; 2. Israfil Mammadov – lieutenant, the first Azerbaijani Hero of the Soviet Union;3. Mehti Huseynzade – intelligence agent, partisan, Hero of the Soviet Union; 4. Ziya Buniyadov – historian, academician, participant of the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union. howing model valour in bat- and the Kursk Bulge, defended the in the war against fascism. tle and also persistent selfless Caucasus and liberated the Ukraine, More than 130 types of arms Slabour on the home front, the Russia, Belarus, the Baltic, Moldova and ammunitions were made then Azerbaijani people contributed sub- and the countries of Eastern Europe. in Azerbaijan, including missiles for stantially towards the general vic- Among the participants in the the famous Katyusha. Our compatri- tory. Together with tens of millions battles for Berlin were daughters ots donated 15kg of gold, 952kg of of sons and daughters of the other of Azerbaijan - R. Ahmadova, S. silver, 320 million roubles and also people of the USSR they forged this Bayramova and S. -

The Battle of Stalingrad: a Behavior Analytic Perspective

REVISTA MEXICANA DE ANÁLISIS DE LA CONDUCTA 2007 NÚMERO 2 (DIC) MEXICAN JOURNAL OF BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS 33, 239-246 NUMBER 2 (DEC) THE BATTLE OF STALINGRAD: A BEHAVIOR ANALYTIC PERSPECTIVE LA BATALLA DE STALINGRADO: UNA PERSPECTIVA BASADA EN EL ANÁLISIS DE LA CONDUCTA MARCO A. PULIDO1 LABORATORIO DE CONDICIONAMIENTO OPERANTE UNIVERSIDAD INTERCONTINENTAL ABSTRACT The purpose of the present paper is to suggest ways in which historians may use behavior analysis as a tool to design research agendas that may help them understand complex human behavior and atypical decision making pro- cesses. This paper presents a brief outline describing the general epistemo- logical and pragmatic virtues of approaching human behavior from a behavior analytic perspective. This outline is followed by a general description of the elements that should be taken into consideration when developing a research agenda based on behavior analytic principles. Lastly a research agenda re- garding a series of puzzling events leading to the encirclement of German Sixth Army during the so called “Battle of Stalingrad,” is used to exemplify the methodology proposed in this paper. Key words: Battle of Stalingrad, behavior analysis, research agenda RESUMEN El propósito de este ensayo es el de sugerir formas en que los historiado- res pueden utilizar los principios del análisis de la conducta para desarrollar 1. Este trabajo fue realizado gracias al apoyo de la Facultad de Psicología y al Instituto de Posgrado e Investigación de la Universidad Intercontinental. El autor agradece a Marco A. Pulido Benítez la corrección de estilo del trabajo y a los revisores anónimos sus valiosas aportaciones al mismo. -

93Rd Annual Conference of the ILO Concludes Its Work

ISSN 1811-1351 №# 1 2 (20) (21) МАРТ JUNE 2005 93rd annual Conference of the ILO concludes its work On June 16 Conference of the International The Conference marked the fourth World The Committee on the Application of Stan- Labour Organization concluded its 93rd annual Day Against Child Labour by calling for the dards noted with respect to freedom of associa- session. The annual Conference of the ILO drew elimination of child labour in one of the world’s tion in Belarus that no real concrete and tangible more than 3,000 delegates, including heads of most dangerous sectors – small-scale mining and measures had been taken by the Government to State, labour ministers and leaders of workers’ quarrying – within five to 10 years. comply with the recommendations of the ILO and employers’ organizations from most of the Confronted with record levels of youth un- Commission of Inquiry. As details of a govern- ILO’s 178 member states. employment in recent years, delegates from ment Plan of Action on freedom of association They discussed the need for urgently elimi- more than 100 countries discussed pathways to were not known yet, the Committee urged that nating forced labour, creating jobs for youth, decent work for youth and the role of the inter- an ILO mission be sent to Belarus, to assist the improving safety at work and tackling what ILO national community in advancing the youth government and also to evaluate the measures Director-General Juan Somavia called a “global employment agenda. The Committee also en- that the government has taken to comply with jobs crisis”. -

What Was the Turning Point of World War Ii?

WHAT WAS THE TURNING POINT OF WORLD WAR II? Jeff Moore History 420: Senior Seminar December 13, 2012 1 World War II was the decisive war of the twentieth century. Millions of people lost their lives in the fighting. Hitler and the Nazis were eventually stopped in their attempt to dominate Europe, but at a great cost to everyone. Looking back at the war, it is hard to find the definitive moment when the war could no longer be won by the Axis, and it is even more difficult to find the exact moment when the tide of the war turned. This is because there are so many moments that could be argued as the turning point of World War II. Different historians pose different arguments as to what this moment could be. Most agree that the turning point of World War II, in military terms, was either Operation Barbarossa or the Battle of Stalingrad. UCLA professor Robert Dallek, Third Reich and World War II specialist Richard Overy, and British journalist and historian Max Hastings, all argue that Stalingrad was the point of the war in which everything changed.1 The principal arguments surrounding this specific battle are that it was the furthest east that Germany ever made it, and after the Russian victory Stalin’s forces were able to gain the confidence and momentum necessary to push the Germans back to the border. On the other hand, Operation Barbarossa is often cited as the turning point for World War II because the Germans did not have the resources necessary to survive a prolonged invasion of Russia fighting both the Red Army and the harsh Russian weather. -

Week Beginning 1St June Title: Why Did Operation Barbarossa Fail?

Lesson 1 – week beginning 1st June Title: Why did Operation Barbarossa fail? WHY DID OPERATION BARBAROSSA FAIL? ‘When Barbarossa commences, the world will hold its breath,’ Hitler said of his bold plan to invade the Soviet Union. The scale of the campaign was certainly huge. Hitler assembled 3 million troops, 3500 tanks and 2700 aircraft for ‘Operation Barbarossa’ - the German code name for the attack on Russia. Why did Hitler break the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact? Hitler invaded the Soviet Union on the 22nd June 1941, ordering his troops to ‘flatten Russia like a hailstorm’. The reasons for the invasion were a mixture of the military and the political. Hitler needed Russia's plentiful raw materials to support his army and population. There was oil in the Caucasus (southern Russia) and wheat in the Ukraine. He was also obsessed by racial ideas. The Russians, he believed, were an inferior ‘Slav’ race which would offer no real resistance (i.e. they wouldn’t be able to fight back) to ‘racially superior’ Germans. Russia's fertile plains could provide even more Lebensraum (living space) than Poland. Russia was also at the heart of world communism, and Hitler detested communists. The Russian Red Army had done very badly during its brief war with Finland in the winter of 1939 – 40. This convinced Hitler the Soviet Union and its Red Army could be beaten in four months. His confidence was also boosted by the fact that in the late 1930s, Stalin, the Soviet dictator, had shot 35,000 officers (43% of all his officers) in ‘purges’ of the Red (Russian) Army. -

Alibek, Tularaemia and the Battle of Stalingrad

Obligations (EC-36/DG.16 dated 4 March 2004, Corr.1 dated 15 Conference of the States Parties (C-9/6, dated 2 December 2004). March 2004 and Add.1 dated 25 March 2004); Information on 13 the Implementation of the Plan of Action for the Implementation Conference decision C-9/DEC.4 dated 30 November 2004, of Article VII Obligations (S/433/2004 dated 25 June 2004); Second www.opcw.org. Progress Report on the OPCW Plan of Action Regarding the 14 Note by the Director-General: Report on the Plan of Action Implementation of Article VII Obligations (EC-38/DG.16 dated Regarding the Implementation of Article VII Obligations (EC- 15 September 2004; Corr.1 dated 24 September 2004; and Corr.2 42/DG.8 C-10/DG.4 and Corr.1 respectively dated 7 and 26 dated 13 October 2004); Report on the OPCW Plan of Action September 2005; EC-M-25/DG.1 C-10/DG.4/Rev.1, Add.1 and Regarding the Implementation of Article VII Obligations (C-9/ Corr.1, respectively dated 2, 8 and 10 November 2005). DG.7 dated 23 November 2004); Third Progress Report on the 15 OPCW Plan of Action Regarding the Implementation of Article One-hundred and fifty-six drafts have been submitted by 93 VII Obligations (EC-40/DG.11 dated 16 February 2005; Corr.1 States Parties. In some cases, States Parties have requested dated 21 April 2005; Add.1 dated 11 March 2005; and Add.1/ advice on drafts several times during their governmental Corr.1 dated 14 March 2005); Further Update on the Plan of consultative process. -

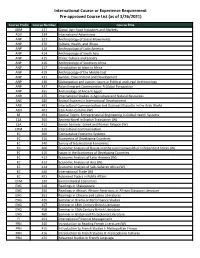

International Course Or Experience Requirement Pre-Approved Course List (As of 3/26/2021)

International Course or Experience Requirement Pre-approved Course List (as of 3/26/2021) Course Prefix Course Number Course Title ABM 427 Global Agri-Food Industries and Markets ADV 334 International Advertising ANP 321 Anthropology of Social Movements ANP 370 Culture, Health, and Illness ANP 410 Anthropology of Latin America ANP 414 Anthropology of South Asia ANP 415 China: Culture and Society ANP 416 Anthropology of Southern Africa ANP 417 Introduction to Islam in Africa ANP 419 Anthropology of the Middle East ANP 431 Gender, Environment and Development ANP 436 Globalization and Justice: Issues in Political and Legal Anthropology ANP 437 Asian Emigrant Communities: A Global Perspective ANP 455 Archaeology of Ancient Egypt ANR 475 International Studies in Agriculture and Natural Resources ANS 480 Animal Systems in International Development ARB 491 Intercultural Communication and Business Etiquette in the Arab World ASN 401 East Asian Cultures (W) BE 491 Special Topics: Entrepreneurial Engineering in Global Health Systems CLA 360 Ancient Novel in English Translation (W) CLA 412 Senior Seminar: Greek and Roman Religion (W) COM 310 Intercultural Communication EC 306 Comparative Economic Systems EC 310 Economics of Developing Countries EC 340 Survey of International Economics EC 406 Economic Analysis of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (W) EC 410 Issues in the Economics of Developing Countries EC 412 Economic Analysis of Latin America (W) EC 413 Economic Analysis of Asia (W) EC 414 Economic Analysis of Sub–Saharan Africa -

We'll Have a Gay Ol'time: Trangressive Sexulaity and Sexual Taboo In

We’ll have a gay ol’ time: transgressive sexuality and sexual taboo in adult television animation By Adam de Beer Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Film Studies in the Faculty of Humanities and the Centre for Film and Media Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN UniversityFebruary of 2014Cape Town Supervisor: Associate Professor Martin P. Botha The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cape Town. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination at any other university. Adam de Beer February 2014 ii Abstract This thesis develops an understanding of animation as transgression based on the work of Christopher Jenks. The research focuses on adult animation, specifically North American primetime television series, as manifestations of a social need to violate and thereby interrogate aspects of contemporary hetero-normative conformity in terms of identity and representation. A thematic analysis of four animated television series, namely Family Guy, Queer Duck, Drawn Together, and Rick & Steve, focuses on the texts themselves and various metatexts that surround these series. The analysis focuses specifically on expressions and manifestations of gay sexuality and sexual taboos and how these are articulated within the animated diegesis. -

War Memory Under the Leonid Brezhnev Regime 1965-1974

1 No One is Forgotten, Nothing is Forgotten: War Memory Under the Leonid Brezhnev Regime 1965-1974 By Yevgeniy Zilberman Adviser: Professor David S. Foglesong An Honors Thesis Submitted To The History Department of Rutgers University School of Arts and Sciences New Brunswick, NJ April, 2012 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Pg. 3 Introduction Pg. 5 1964-1967: Building the Cult Pg. 18 a) Forming the Narrative: Building the Plot and Effacing the Details Pg. 21 b) Consecrating the War: Ritual, Monument and Speech Pg. 24 c) Iconography at Work: Soviet War Poster Pg. 34 d) Digitizing the War: On the Cinema Front Pg. 44 1968-1970: Fascism Revived and the Battle for Peace Pg. 53 a) This Changes Everything: Czechoslovakia and its Significance Pg. 55 b) Anti-Fascism: Revanchism and Fear Pg. 59 c) Reviving Peace: The Peace Cult Pg. 71 1970-1974: Realizing Peace Pg. 83 a) Rehabilitating Germany Pg. 85 b) Cinema: Germany and the Second World War on the Film Screen Pg. 88 c) Developing Ostpolitik: War memory and the Foundations for Peace Pg. 95 d) Embracing Peace Pg. 102 Conclusion: Believing the War Cult Pg. 108 Bibliography Pg. 112 3 Acknowledgements Perhaps as a testament to my naivety, when I embarked upon my journey toward writing an honors thesis, I envisioned a leisurely and idyllic trek toward my objective. Instead, I found myself on a road mired with multiple peaks and valleys. The obstacles and impediments were plentiful and my limitations were numerous. Looking back now upon the path I traveled, I realize that I could not have accomplished anything without the assistance of a choice collection of individuals. -

THE BATTLE of STALINGRAD Belligerents

THE BATTLE OF STALINGRAD DATE: AUGUST 23 1942 – FEBRUARY 02 1943 Belligerents Germany Soviet Union Italy Romania Hungary Croatia The Battle of Stalingrad was a brutal military campaign between Russian forces and those of Nazi Germany and the Axis powers during World War 2. The battle is infamous as one of the largest, longest and bloodiest engagements in modern warfare: from August 1942 through February 1943, more than two million troops fought in close quarters – and nearly two million people were killed or injured in the fighting, including tens of thousands of Russian civilians. But the Battle of Stalingrad (one of Russia’s important industrial cities) ultimately turned the tide of World War 2 in favor of the Allied forces. PRELUDE In the middle of World War 2 – having captured territory in much of present-day Ukraine and Belarus in the spring on 1942 – Germany’s Wehrmacht forces decide to mount an offensive on southern Russia in the summer of that year. Under the leadership of ruthless head of state Joseph Stalin, Russian forces had already successfully rebuffed a German attack on the western part of the country – one that had the ultimate goal of taking Moscow – during the winter of 1941-42. However, Stalin’s Red Army had suffered significant losses in the fighting, both in terms of manpower and weaponry. Stalin and his generals, including future Soviet Union leader Nikita Khrushchev, fully expected another Nazi attack to be aimed at Moscow. However, Hitler and the Wehrmacht had other ideas. They set their sights on Stalingrad; the city served as an industrial center in Russia, producing, among other important goods, artillery for the country’s troops. -

Editors' Introduction Studying the International

Editors’ Introduction Studying the International Relations of the Asia Pacifi c: What Is the Region, What Are the Issues? Shaun Breslin and Richard Higgott Introduction or nearly three decades now, various scholars, analysts and practitioners have been hypothesising about the rise of the ‘Pacific’ or ‘Asian’ centuries. FAnalyses have been driven variously by the agendas of international security, international economic relations and increasingly a combination of the two. Though confidence in Asia’s rise was somewhat dented by the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the early years of the 21st century have seen the Pacific Century narrative begin to regain strength once again. The primary driver of this renewed rhetoric is growing American interests (if not outright concerns) about the impact of China (see Shambaugh, in Volume 2). Indeed, the recent flurry of activity by those seeking to establish the correctness of their theoretical starting point for studying the region (covered in Volume 1) is largely concerned with predicting the consequences of China’s rise; and trying to influence a policy audience (primarily in Washington) to act now to shape the nature of this rise. But it’s not just about China. As perhaps most forcefully expressed in the writings of Kishore Mahbubani (2007), there is also a growing assertiveness in some parts of Asia itself over the shift in power from the Western to eastern hemisphere. Earlier scholars from the region argued that Asia did not have to accede to the Western way of doing things – the region could ‘Say No!’ to the imposition of alien political, economic and social structures and do things their own way. -

Family and Satire in Family Guy

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-06-01 Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Ryan, Reilly Judd, "Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5583. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5583 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Darl Larsen, Chair Sharon Swenson Benjamin Thevenin Department of Theatre and Media Arts Brigham Young University June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Reilly Judd Ryan All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Where Are Those Good Old Fashioned Values? Family and Satire in Family Guy Reilly Judd Ryan Department of Theatre and Media Arts, BYU Master of Arts This paper explores the presentation of family in the controversial FOX Network television program Family Guy. Polarizing to audiences, the Griffin family of Family Guy is at once considered sophomoric and offensive to some and smart and satiric to others.