Grus Canadensis; Aves: Gruidae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantifying Crop Damage by Grey Crowned Crane Balearica

QUANTIFYING CROP DAMAGE BY GREY CROWNED CRANE BALEARICA REGULORUM REGULORUM AND EVALUATING CHANGES IN CRANE DISTRIBUTION IN THE NORTH EASTERN CAPE, SOUTH AFRICA. By MARK HARRY VAN NIEKERK Department of the Zoology and Entomology, Rhodes University Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2010 Supervisor: Prof. Adrian Craig i TABLE OF CONTENTS List of tables…………………………………………………………………………iv List of figures ………………………………………………………………………...v Abstract………………………………………………………………………………vii I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 1 Species account......................................................................................... 3 Habits and diet ........................................................................................... 5 Use of agricultural lands by cranes ............................................................ 6 Crop damage by cranes ............................................................................. 7 Evaluating changes in distribution and abundance of Grey Crowned Crane………………………………………………………..9 Objectives of the study………………………………………………………...12 II. STUDY AREA…………………………………………………………………...13 Locality .................................................................................................... 13 Climate ..................................................................................................... 15 Geology and soils ................................................................................... -

An Assessment of Threats to Anatidae in Iran

Bird Conservation International (2015) 25 :242 –257 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S0959270914000264 An assessment of threats to Anatidae in Iran ELHAM NOURANI , MOHAMMAD KABOLI and BEN COLLEN Summary The network of wetland systems in Iran provides valuable staging and wintering areas for waterbirds in the African-Western Eurasian flyways. The West Siberian/Caspian/Nile popula- tions of Anatidae (ducks, geese and swans) regularly overwinter and stop over in Iran, and are considered an economically and culturally important group of birds in the country. Conservation of such migratory birds requires the identification of key threat factors impacting them throughout the flyway. Since documented data on the status and threats facing Anatidae in Iran are very scarce, in this paper, we attempted to determine the general population trends for the 26 Anatidae species in Iran, using annual waterbird census data, and to identify and score the most important threat factors affecting each species, by consulting the top ornithologists and pro- fessional birdwatchers in the country by means of a survey. Our results indicate that the most prevalent threats affecting all 26 species are dam construction, water management practices, and hunting. Our results provide the necessary material for Red List assessment of these species at the national level, an important tool for conservation priority setting within Iran and in the flyway. Introduction Waterbirds have long been the subject of many international conservation agreements. The Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971) and the Agreement on the Conservation of African- Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA, 1999), among others, urge countries to work together to save migratory waterbirds through the flyway concept. -

Brolga Grus Rubicunda

Action StatementNo 119 Brolga Grus rubicunda Indexof Action Stetements *xDescription and Distribution * LifeHistorv and Ecoloqv *ConservationStatus *Decline andThreats *ManaqeqentAgtion *xReferences **Compilers Brolga, Grus rubicunda (illustrationby SusannaHaffenden) Descriptionand Distribution The BrolgaGrus rubicunda (Perry) is a large,long-necked 'lr cranestanding to 1.8metres in height.They have long, darklegs and their plumage is predominanflylight grey in colour.The average wing span of an adultis 1.7-2.4 "k-: metres.The adultmale weighs 4.7-8.7 kilograms and the female3.7-7 .3 kilograms(Marchant and Higgins 1993). Adultshave a conspicuousorange-red head which contrastswith the barecrown of greenish-greyskin and the darkerpendulous dewlap. The billis dark,long and straightand relativelylarge compared to the head.The iris ..;;, is yellowto reddish-orange.lmmatures (up to 10 months of age)have a grey,fully feathered head and the irisis darkbrown. Juveniles (11to22 months)gradually lose the headfeathering and attainthe red headcolouring. A fulldescription can be foundin Marchantand Higgins illrtr{but}on In Vlcteria (1ee3) +b€fere 1970 I sincg ,1570 {s+urce: S#as of tf,efonsr $,!#dlds.FlftE lgSSl The Brolgais distributedacross New Guinea, northern andsouth-eastern Australia (Blakers et al. 1g84, Marchantand Higgins1993). The populationsin Victoria andSouth Australia may now be isolatedfrom the northernpopulations as thereappear to be onlyscattered birdsin NewSouth Wales. In Victoria,birds are currentlyfound in the south-west,the NorthernPlains and adjacentparts of the MurrayRiver (Emison et al.1987).The specieswas formerlymore widely distributed and common,being recorded from the Melbournearea, Gippsland and North-easternVictoria (White 1e83). Life historyand ecology The Brolgais omnivorousand utilisesa diverserange of fooditems on a seasonalbasis. -

Wintering Behavior of a Siberian Crane Grus Leucogeranus in Niigata, Japan, with Special Regard to Food, Foraging and Vocal Habits

Ornithol Sci 17: 187 – 194 (2018) ORIGINAL ARTICLE Wintering behavior of a Siberian Crane Grus leucogeranus in Niigata, Japan, with special regard to food, foraging and vocal habits Akira CHIBA#,* 1-13-11 Terao-Higashi, Niigata 950–2054, Japan ORNITHOLOGICAL Abstract An immature Siberian Crane Grus leucogeranus straggled to Niigata, Japan, in late autumn 2016 and remained over winter in an area of rice fields. In this SCIENCE paper the bird’s diet and foraging behavior during winter 2016/2017 are described. © The Ornithological Society During daytime, the crane foraged alone, mostly on post-harvest rice fields where of Japan 2018 it fed almost exclusively on Water Chestnut Eleocharis kuroguwai tubers. Other foods, such as rice grains, earthworms, grasshoppers and fishes, though eaten, were negligible in the bird’s diet. The density of water chestnut tubers in the foraging area was estimated to be 3.1±3.0/m2 and the biomass 2.0±2.1 g/m2. The crane’s foraging behavior generally included removing any superficial covering material, digging into and removing the soil, exploring the food in the beak and then consuming it with or without rinsing it in groundwater. During foraging, the frequency of food intake varied from 4.8±2.0/10 min to 41.3±9.5/10 min. These results indicate the great significance of water chestnuts in the diet of the Siberian Crane in winter, although further study is necessary for generalization. Key words Diet, Foraging, Grus leucogeranus, Rice field, Water chestnuts The Siberian Crane Grus leucogeranus is regarded al. 2017). Such information has contributed to our as a critically endangered species by the International understanding of the current situation of the species Union for Conservation of Nature, with a global pop- in the wild, and has promoted further investigation ulation of 3,500 to 4,000 individuals (Bird Life Inter- and conservation. -

First Arizona Record of Common Crane

Arizona Birds - Journal of Arizona Field Ornithologists Volume 2020 FIRST ARIZONA RECORD OF COMMON CRANE JOE CROUSE,1125 W. SHULLENBARGER DR., FLAGSTAFF, AZ 86005 The first record of a Common Crane (Grus grus), a Eurasian species, in Arizona was reported in May 2017 at Mormon Lake in Coconino County. It remained at this lake through September 2017. In 2019 a Common Crane was reported 11 May through 31 August at Mormon Lake. The 2017 record has been reviewed and accepted by the Arizona Bird Committee (Rosenberg et al. 2019), and the 2019 bird has been accepted as the same individual. The Common Crane is a widespread crane found in Europe, Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Breeding occurs across northern Europe and northern Asia, from Norway on the west to Siberia on the east. Nonbreeding populations are found as far west as Morocco and to southeastern China. A resident population exists in Turkey (NatureServe and IUCN 2017, Figure 1). Preferred habitat for both breeding and nonbreeding birds is small ponds or lakes, wet meadows, and other wetland areas (Cramp and Simmons 1980). Figure 1. Common Crane Distribution Cramp and Simmons (1980) stated that the Common Crane range in western Europe has had a “marked” decrease since the Middle Ages. They attributed this to the draining of nesting areas. Since 1950 improved habitat protections, recolonization in previously inhabited areas, and designation as a protected species have resulted in a dramatic increase in the overall population (Prange 2005). Although its range has decreased, it continues to be extensive enough, along with the increase in its already large population, to give it the status of a species of “Least Concern” (BirdLife International 2016, NatureServe and IUCN 2019). -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

An Assessment of Threats to Anatidae in Iran

Nourani, E; Kaboli, M; Collen, B; (2014) An assessment of threats to Anatidae in Iran. Bird Conservation International 1 - 16. 10.1017/S0959270914000264. Downloaded from UCL Discovery: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1450324 ARTICLE An assessment of threats to Anatidae in Iran Elham Nourani1, Mohammad Kaboli*1, Ben Collen2 1Department of Environment, Faculty of Natural Resources, University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. 2Centre for Biodiversity & Environment Research, Department of Genetics, Evolution & Environment, University College London, London, United Kingdom. *Corresponding author: Mohammad Kaboli, Tel: +98-2632223044; Fax: +98-2632229721;Email: [email protected] Abstract The network of wetland systems in Iran provides valuable staging and wintering areas for waterbirds in the African-Western Eurasian flyway. The West Siberian/Caspian/Nile population of Anatidae (ducks, geese and swans) regularly overwinters and stops-over in Iran, and is considered an economically and culturally important group of birds in the country. Conservation of such migratory birds requires the identification of the key threat factors impacting them throughout the flyway. Since documented data on the status and threats facing Anatidae in Iran is very scarce, in this paper, we attempted to determine the general population trend for the 26 Anatidae species in Iran using annual waterbird census data and to identify and score the most important threat factors affecting each species by consulting the top ornithologists and professional birdwatchers in the country by means of a survey. Our results indicate that the most prevalent threats affecting all 26 species are dam construction, water management practices, and hunting. Our results provide the necessary material for Red List assessment of these species at the national level, an important tool for conservation priority setting within Iran and in the flyway. -

Voice Breaking in Adolescent Red-Crowned Cranes (Grus Japonensis)

Voice breaking in adolescent red-crowned cranes (Grus japonensis) Anna V. Klenova1,4), Ilya A. Volodin1,2,5), Elena V. Volodina2,5) & Kirill A. Postelnykh3,6) (1 Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Faculty of Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Vorobievy Gory, Moscow 119991, Russia; 2 Scientific Research Department, Moscow Zoo, B. Gruzinskaya, 1, Moscow 123242, Russia; 3 Oka Biosphere State Nature Reserve, Oka Crane Breeding Centre, Ryazan region 391072, Russia) (Accepted: 17 November 2009) Summary Voice breaking is a process associated with puberty of human males that also occurs in adolescence in some birds. This study reports the jump-like vocal changes occurring during voice breaking in adolescent red-crowned cranes (Grus japonensis). We investigated acoustic parameters of chirp and trill calls during vocal ontogenesis from hatching to the age of 1.5 years in 17 male and 31 female captive red-crowned cranes and compared them with definitive calls of 5 male and 8 female conspecific adults. During voice breaking, trills and chirps of both sexes contained two non-overlapping independent fundamental frequencies: the upper one, representing the retained juvenile frequency, and the lower one, the newly attained adult frequency. Before voice breaking, the calls contained only the upper frequency, whereas after it only the lower one. Voice breaking occurred between the age of 7 and 11.5 months. We test whether sex, dates of birth and body mass gain are associated with voice breaking and speculate whether voice breaking triggers the disruption of the parent– chick bond or vice versa, or both events are driven by a third, yet unidentified trigger. -

And Siberian Cranes (G. Leucogeranus) in Eastern Siberia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University COMPARATIVE BREEDING ECOLOGY OF LESSER SANDHILL CRANES (GRUS CANADENSIS CANADENSIS) AND SIBERIAN CRANES (G. LEUCOGERANUS) IN EASTERN SIBERIA A Dissertation by TSUYOSHI WATANABE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2006 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences COMPARATIVE BREEDING ECOLOGY OF LESSER SANDHILL CRANES (GRUS CANADENSIS CANADENSIS) AND SIBERIAN CRANES (G. LEUCOGERANUS) IN EASTERN SIBERIA A Dissertation by TSUYOSHI WATANABE Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Co-Chairs of Committee, R. Douglas Slack Felipe Chavez-Ramirez Committee Members, Nova J. Silvy Larry J. Ringer Interim Head of Department, Delbert M. Gatlin III December 2006 Major Subject: Wildlife and Fisheries Sciences iii ABSTRACT Comparative Breeding Ecology of Lesser Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis canadensis) and Siberian Cranes (G. leucogeranus) in Eastern Siberia. (December 2006) Tsuyoshi Watanabe, B.A., Hokkaido University for Education; M.S., Southern Connecticut State University; D.V.M., Michigan State University Co-Chairs of Advisory Committee: Dr. R. Douglas Slack Dr. Felipe Chavez-Ramirez Populations of Lesser Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis canadensis) have been increasing during the last decades in Eastern Siberia, an area historically known as breeding grounds of endangered Siberian Cranes (G. leucogeranus). Significant overlap in niche dimensions between the two species may occur and could lead to competition between them. -

Hooded Crane Nabe-Zuru (Jpn) Grus Monacha

Bird Research News Vol.4 No.1 2007.1.12. Hooded Crane Nabe-zuru (Jpn) Grus monacha Morphology and classification Life history Classification: Gruiformes Gruidae 123456789101112 wintering Total length: About 100cm Wing length: 480-530mm period migration breeding migration Tail length: 160-190mm Culmen length: 93-107mm Tarsus length: 200-230mm Breeding system: Weight: ♂ 3280-4870g ♀ 3400-3740g Hooded Cranes are monogamous. It is assumed that once they have paired, they usually maintain the pair-bond. When a partner Total length after del Hoyo (1996) and the others after Kiyosu (1978). died, however, the bereaved one sometimes mates with another bird again. Appearance: Male and female are simi- Age of the first breeding: lar in plumage coloration. Males and females are sexually mature at the age of about three They have an area of bare and five years, respectively, but unpaired females do not lay eggs, skin on the forehead. The even if they are mature (Ellis et al. 1996). skin exposed above the eye is red, but the other is Nest: black. They are charcoal There is no detailed information about the nest, but the size is as- gray all over except for sumed to vary greatly from one bird to another. There seems to be the area from the head to a nest with a diameter of several meters and a height of one meter. the nape, which is white. The study of Fujimaki et al. (1989) showed that they built a nest at They have tan bills and a height of 15-20cm above the water. The diameter of a nest was black legs. -

2020 National Bird List

2020 NATIONAL BIRD LIST See General Rules, Eye Protection & other Policies on www.soinc.org as they apply to every event. Kingdom – ANIMALIA Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias ORDER: Charadriiformes Phylum – CHORDATA Snowy Egret Egretta thula Lapwings and Plovers (Charadriidae) Green Heron American Golden-Plover Subphylum – VERTEBRATA Black-crowned Night-heron Killdeer Charadrius vociferus Class - AVES Ibises and Spoonbills Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) Family Group (Family Name) (Threskiornithidae) American Oystercatcher Common Name [Scientifc name Roseate Spoonbill Platalea ajaja Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) is in italics] Black-necked Stilt ORDER: Anseriformes ORDER: Suliformes American Avocet Recurvirostra Ducks, Geese, and Swans (Anatidae) Cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae) americana Black-bellied Whistling-duck Double-crested Cormorant Sandpipers, Phalaropes, and Allies Snow Goose Phalacrocorax auritus (Scolopacidae) Canada Goose Branta canadensis Darters (Anhingidae) Spotted Sandpiper Trumpeter Swan Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Ruddy Turnstone Wood Duck Aix sponsa Frigatebirds (Fregatidae) Dunlin Calidris alpina Mallard Anas platyrhynchos Magnifcent Frigatebird Wilson’s Snipe Northern Shoveler American Woodcock Scolopax minor Green-winged Teal ORDER: Ciconiiformes Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae) Canvasback Deep-water Waders (Ciconiidae) Laughing Gull Hooded Merganser Wood Stork Ring-billed Gull Herring Gull Larus argentatus ORDER: Galliformes ORDER: Falconiformes Least Tern Sternula antillarum Partridges, Grouse, Turkeys, and -

Conservation Status of Cranes

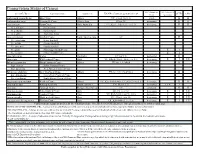

Conservation Status of Cranes IUCN Population ESA Endangered Scientific Name Common name Continent IUCN Red List Category & Criteria* CITES CMS Trend Species Act Anthropoides paradiseus Blue Crane Africa VU A2acde (ver 3.1) stable II II Anthropoides virgo Demoiselle Crane Africa, Asia LC(ver 3.1) increasing II II Grus antigone Sarus Crane Asia, Australia VU A2cde+3cde+4cde (ver 3.1) decreasing II II G. a. antigone Indian Sarus G. a. sharpii Eastern Sarus G. a. gillae Australian Sarus Grus canadensis Sandhill Crane North America, Asia LC II G. c. canadensis Lesser Sandhill G. c. tabida Greater Sandhill G. c. pratensis Florida Sandhill G. c. pulla Mississippi Sandhill Crane E I G. c. nesiotes Cuban Sandhill Crane E I Grus rubicunda Brolga Australia LC (ver 3.1) decreasing II Grus vipio White-naped Crane Asia VU A2bcde+3bcde+4bcde (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Balearica pavonina Black Crowned Crane Africa VU (ver 3.1) A4bcd decreasing II B. p. ceciliae Sudan Crowned Crane B. p. pavonina West African Crowned Crane Balearica regulorum Grey Crowned Crane Africa EN (ver. 3.1) A2acd+4acd decreasing II B. r. gibbericeps East African Crowned Crane B. r. regulorum South African Crowned Crane Bugeranus carunculatus Wattled Crane Africa VU A2acde+3cde+4acde; C1+2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing II II Grus americana Whooping Crane North America EN, D (ver 3.1) increasing E, EX I Grus grus Eurasian Crane Europe/Asia/Africa LC unknown II II Grus japonensis Red-crowned Crane Asia EN, C1 (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Grus monacha Hooded Crane Asia VU B2ab(I,ii,iii,iv,v); C1+2a(ii) decreasing E I I,II Grus nigricollis Black-necked Crane Asia VU C2a(ii) (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Leucogeranus leucogeranus Siberian Crane Asia CR A3bcd+4bcd (ver 3.1) decreasing E I I,II Conservation status of species in the wild based on: The 2015 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, www.redlist.org CRITICALLY ENDANGERED (CR) - A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future.