Forestry and Woodland History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nanteos Cup: 'Holy Grail' Stolen from Sick Woman's Home

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/ Adam Lusher Tuesday 15 July 2014 Nanteos Cup: 'Holy Grail' stolen from sick woman's home Medieval chroniclers claimed Joseph of Arimathea took it to Britain In what some might call a real-life quest for the Holy Grail, police were last night hunting burglars who stole a religious relic said to be the cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper. West Mercia Police confirmed that the Nanteos Cup, a wooden bowl which may or may not have links to the Holy Land and the power to bestow eternal life, had been stolen in a burglary in Weston Under Penyard, a small village in Herefordshire. A police spokeswoman said: “I don’t want to say we are hunting the Holy Grail, but police are investigating the burglary. “The item stolen is known as the Nanteos Cup. If you do a bit of Googling, you will see some people think it is the Holy Grail.” According to legend – and Google - the cup was used by Joseph of Arimathea to catch Christ’s blood while interring Him in his tomb. Medieval chroniclers claimed Joseph took the cup to Britain and founded a line of guardians to keep it safe. It ended up in Nanteos Mansion near Aberystwyth, Wales, attracting visitors who drank from it, believing it had healing powers. It now measures 10cm by 8.5cm – after bits were nibbled off by the sick in the hope of a miracle cure. Belief in the cup’s holy powers appears to have persisted despite a 2004 television documentary in which experts found it dated from the 14th Century, some 1,400 years after the Cruxifiction. -

Relic Thought to Be 'Holy Grail', Stolen in Burglary

http://m.worcesternews.co.uk/news/ Relic thought to be 'Holy Grail', stolen in burglary Ancient relic, Nanteos Cup, once thought to be the legendary Holy Grail, stolen in burglary at Weston under Penyard, near Ross Updated on 8:25pm Tuesday 15th July 2014 in News AN ancient relic that was once thought to be the Holy Grail has been stolen from a house in Herefordshire. In the last few minutes, West Mercia Police has issued a statement saying that a wooden chalice, known as the Nanteos Cup, has been stolen in a bur4glary at Weston under Penyard, near Ross. The property was broken into between 9.30amon Monday, July 7, and 9.30am yesterday (Monday, July 14). The police name the Nanteos Cup as reported stolen, describing it as a dark wood cup kept in a blue velvet bag. According to Wikipedia, the Nanteos Cup is a medieval bowl, held for many years at Nanteos Mansion, near Aberystwyth, which legend claimed to be the Holy Grail. According to tradition, the Holy Grail was brought to Britain from the Holy Land by Joseph of Arimathea, who is said to have founded a religious settlement at Glastonbury. During the Dissolution of the Monasteries, some of the monks fled to Strata Florida Abbey in mid-Wales, bringing the relic with them. After that abbey closed, the cup ended up in the hands of the Powell family of Nanteos through marriage. The cup had a reputation for healing and people would drink water from it in the hope of curing their ailments. The Nanteos cup deteriorated greatly over the years and is no longer at the mansion, as it went with the last member of the Powell family when they moved out of Nanteos in the 1950s. -

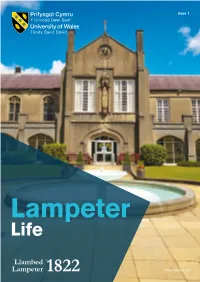

Lampeter Life

Issue 1 Lampeter Life www.uwtsd.ac.uk University of Wales Trinity Saint David: Lampeter Life | 1 Welcome Welcome to the first edition of ‘Lampeter undergraduates at the University has the past few months and in this edition Life’. The University has had another improved in two consecutive years to 85% we look at some of the highlights during successful year as we continue to move from 79% two years ago. This improvement graduation, the opening of the University’s up in all the major league tables. The has seen UWTSD climb 44 places in the UK Academy of Sinology as well as a visit to the recent Times and The Sunday Times Good Universities NSS table. This is testament to campus by BBC broadcaster Huw Edwards University Guide 2018 showed that the the hard work and quality of academic staff who was guest lecturer at this year’s Cliff University has been ranked 16th overall we have at the University. Tucker Memorial Lecture. in the UK for ‘Teaching Quality’ and third in Wales. These results come swiftly after We’ve just welcomed a new cohort of Finally, we’d like to thank you for your the University was recently awarded its students to the Lampeter campus and we continued support as we look forward to highest ever Student Satisfaction score look forward to another busy academic another exciting year for the University. in the National Student Survey 2017 year. ‘Lampeter Life’ gives you a taste of (NSS). Satisfaction amongst final year what has been happening on campus over Contents 4 12 Lord Elystan-Morgan Academy of Sinology receives Honorary -

AG Prys-Jones Papers

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - A. G. Prys-Jones Papers, (GB 0210 PRYNES) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 05, 2017 Printed: May 05, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows ANW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.;AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/g-prys-jones-papers-2 archives.library .wales/index.php/g-prys-jones-papers-2 Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk A. G. Prys-Jones Papers, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Hanes gweinyddol / Braslun bywgraffyddol | Administrative history | Biographical sketch ......................... 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 4 Trefniant | Arrangement .................................................................................................................................. 4 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | -

Aberystwyth University Women's Club 1955-2015 (PDF)

I. Beginnings Three of us, Mollie Reynolds, Hannah Harbury and myself were having coffee together, and we saw the wife of one of the members of staff going past. In that pre-feministic age, the custom was to refer to ‘the wife of this-or-that professor’. Anyway, not one of us could remember who she was, and we agreed that that was a laughable situation. You have to remember that only a fifth of the number of students that are here today were at the College at that time; the majority of the staff lived in the town and the professors either walked or bicycled to the College. There were very few houses on Waunfawr, and nearly every College department was in the old building. Mollie suggested that we start a Club. And so we set about composing a letter and having copies made. There was no such thing as photocopying then. We were surprised by the reaction, everyone was enthusiastic, and I found myself treasurer of this new Club, much to my husband’s unease! This is how Mair Williams described the formation of the University of Wales Women’s Club (or the College Women’s Club as it was first called) in Yr Angor in 1995 on the occasion of its 40th anniversary. She later recalled that this had happened at a College event around 1954, about the time that Goronwy Rees had arrived at Aberystwyth. Mollie Reynolds suggestion that we start a Club stemmed from the fact that she had been a member of a Women’s Club at the London School of Economics where her husband, Philip A. -

Vancouver Welsh Society

Newsletter March 2006 / Cylchgrawn Mawrth 2006 THE WELSH SOCIETY OF VANCOUVER Mawrth March 2006 2006 Cymdeithas Gymraeg Vancouver Cambrian News Society Newsletter – Cylchgrawn y Gymdeithas James Memorial at Ynys Angharad Park, Pontypridd CAMBRIAN HALL, 215 East 17th Ave, Vancouver B.C. V5V 1A6 2 Newsletter March 2006 / Cylchgrawn Mawrth 2006 The Cambrian News WELSH SOCIETY, VANCOUVER From The Editor: Officers The memorial featured on the front page President: was designed by Sir William Goscombe Jane Byrne (604) 732-5448 John. It consists of two life-sized bronze Vice-President: figures representing Poetry and Music fixed Lynn Owens-Whalen 266-2545 in Blue Pennant stone. Between the bases is Secretary: a profile of the heads of Evan and James Eifion Williams 469-4904 James. There are inscriptions in Welsh and Treasurer: English; the English one reads: Gaynor Evans 271-3134 In memory of Evan James and James James Membership Secretary: father and son, of Pontypridd, who, inspired Heather Davies 734-5500 by a deep and tender love of their native Immediate Past President: land united poetry to song and gave Wales Tecwyn Roberts 464-2760 her National Anthem, ‘Hen Wlad fy Nhadau’. Directors: John Cann This year celebrates the 150th Anniversary Allan Hunter of its composition, the words by Evan (Ieuan Selwyn Jones ap Iago) and the music by James (Iago ap Mary Lewis Ieuan). Indeed Pontypridd has much to David Llewelyn Williams celebrate this year since it is also the 250th Anniversary of the old bridge and a well Contacts known native son, singer Thomas Jones Building Committee: (Woodward), was knighted in the New Allan Hunter 594-0935 Year’s Honours List. -

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF WALES Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees held at the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth on Friday, 28th April 2017 Present: Rhodri Glyn Thomas, President Colin R. John, Treasurer Iwan Davies Hugh Thomas Susan Davies Huw Williams Lord Aberdare Richard Houdmont Phil Cooper Liz Siberry Gwilym Jones Executive Team: Linda Tomos Chief Executive and Librarian David Michael Director of Corporate Resources Pedr ap Llwyd Director of Collections and Public Programmes Staff: Mererid Jones Head of Finance and Enterprise (Section 4) Carol Edwards Governance Manager and Clerk to the Board of Trustees Annwen Isaac Human Resources Adviser Also in attendance: Mary Ellis MALD Doug Jones Partnership Council Geralene Mills Natural Resources Wales (observer) Introduction to Welsh Journals Online Dr Dafydd Tudur, Manager of the Digital Access Division, gave an introduction to Welsh Journals Online. Following the presentation, Members commented on the usefulness of this resource to them in their research, and that consideration should be given to using it as a resource for teaching research skills in secondary schools, and to get school children to realise that the digital isn’t 1 always a true reflection of the original. It was noted that the option of downloading would be very useful, and that the Library should consider the possibility of using the resource as a commercial income stream. It was asked what the current gap in provision is - 479 titles are included. Dafydd promised to research to discover what percentage this is of the total number available during that period. ACTION: DAFYDD TO RESEARCH TO SEE WHAT PERCENTAGE OF THE TOTAL AMOUNT THE 479 TITLES AVAILABLE ON THE WELSH JOURNALS ONLINE WEBSITE REPRESENTS Pedr thanked Owain and Dafydd for their work and for the time that has been committed to this project. -

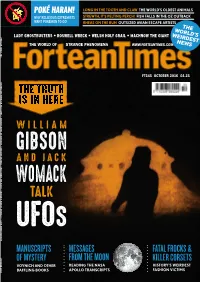

Womack and Gibson the Truth Is in Here

POKÉ HARAM! LONG IN THE TOOTH AND CLAW THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS WHY RELIGIOUS EXTREMISTS STREWTH, IT'S PELTING PERCH! FISH FALLS IN THE OZ OUTBACK WANT POKÉMON TO GO! RHEAS ON THE RUN OUTSIZED AVIAN ESCAPE ARTISTS THE WOR THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA LD’S LADY GHOSTBUSTERS • ROSWELL WRECK • WELSH HOLY GRAIL • MACHNOWWWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM THE GIANT WEIRDES FORTEAN TIMES 345 NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM FT345 OCTOBER 2016 £4.25 GIBSON AND WOMACK TALK UFOS • MANUSCRIPTS OF MYSTERY • THE TRUTH IS IN HERE WILLIAM FA GIBSON SHION VICTIMS • MACHNOW THE GIANT • WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS • LADY GHOSTBUSTERS AND JACK WOMACK TALK UFOS MANUSCRIPTS MESSAGES FATALFROCKS& OCTOBER 2016 OFMYSTERY FROMTHEMOON KILLERCORSETS VOYNICH AND OTHER READING THE NASA HISTORY'S WEIRDEST BAFFLING BOOKS APOLLO TRANSCRIPTS FASHION VICTIMS LISTEN IT JUST MIGHT CHANGE YOUR LIFE LIVE | CATCH UP | ON DEMAND Fortean Times 345 strange days Pokémon versus religion, world’s oldest creatures, fate of Flight MH370, rheas on the run, Bedfordshire big cat, female ghostbusters, Australian fi sh fall, Apollo transcripts, avian CONTENTS drones, pornographer’s papyrus – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 14 ARCHAEOLOGY 25 ALIEN ZOO the world of strange phenomena 15 CLASSICAL CORNER 28 NECROLOG 16 SCIENCE 29 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 18 GHOSTWATCH 30 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 32 FROM OUTER SPACE TO YOU JACK WOMACK has been assembling his collection of UFO-related books for half a century, gradually building up a visual and cultural history of the saucer age. Fellow writer and fortean WILLIAM GIBSON joined him to celebrate a shared obsession with pulp ufology, printed forteana and the search for an all too human truth.. -

BRECKNOCK DECORATIVE & FINE ARTS SOCIETY National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth Guided Tour of Collections Wednesday 26Th Ap

BRECKNOCK DECORATIVE & FINE ARTS SOCIETY National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth Guided Tour of Collections th Wednesday 26 April 2017 Founded in 1907, the Library is entitled to receive a copy of every book published in the U.K. Wales' largest library is where many of the most important Welsh publications are kept and these include the Black Book of Carmarthen, one of the earliest surviving manuscripts written solely in the Welsh language. As well as books and other printed publications, there are over a million maps, along with photographs, an impressive paintings collection and sound and video recordings. The coach will leave Brecon Bus Station Car Park at 10am and will arrive in time for lunch, which will be at your own expense. Following lunch we will have a ‘Guided Tour of the Collections’ led by two of NLW art curators Morfudd Bevan & Sian Wyn Jones. In addition there will be the opportunity to see the Nanteos Cup and to visit exhibitions ‘Fallen Poets: Edward Thomas & Hedd Wyn’, Stories of the Saints’, ‘Pete Davies: A Lifetime in Photography’ and ‘Cover to Cover’ (please visit the website of the National Library of Wales, click on ‘What’s on’ & scroll down to ‘Exhibitions’ for further details, including information on the Nanteos Cup. The cost of the day is £29.50 (coach & guided tour fee). Estimated return time in Brecon 18.30 Please also note that whilst there is NADFAS Member-to-Member liability insurance, BDFAS does not have insurance for loss or personal injury. Please tear off the slip below and either take it to the Travel Desk at the Monthly Lectures or send it to: Miss Pat Wilkie, Bendithion, 15 Maesmawr,Talybont-on-Usk, Powys. -

Welsh Language News Or News in the Welsh Language

Cambrian Heritage Society Newsletters. Language note: The original title of our newsletter was Newyddion Cymraeg, literally Welsh Language News or News in the Welsh Language. Since most of the newsletter has been and will continue to be written in the English language but about Welsh-related issues and events, a more correct title would be Newyddion Cymreig (meaning Welsh News, where the title means related to Wales in general rather than the language). Some of the issues below were published under the former and less correct title bu thave had their titles changed below for the sake of correctness. Newyddion Cymreig Cambrian Heritage Society Madison, wisconsin Christmas 2012 newsletter Vol. 18 # 2 Do something Welsh with your family this Christmas! Please join us for a fun, interactive, child-friendly performace of “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” a short story by Dylan Thomas Performed by Michael O’Rourke Saturday, December 8th, 11:00am – 1:30pm Sequoya Library 4340 Tokay Blvd. Madison, WI Te Bach (cider & snacks) to follow. Call Trina Muich at 957-2961 for details. Welsh Weekend #7: Mark Your Calendars By:Mary Williams-Norton Seventh Welsh Weekend for Everyone (Seithfed Penwythnos Cymreig i Bawb) is scheduled for May 3, 4, and 5, 2013, in Appleton. Following the very successful model of the weekend this past May in Reedsburg, the event will begin with a supper and “pub night” at the recommended hotel, the Radisson Paper Valley in Appleton, on Friday night, May 3, continue with workshops, children’s activities, displays, supper, Noson Lawen, and awarding of the Eisteddfod Chair on May 4, and conclude with the State Gymanfa Ganu on Sunday afternoon, May 5. -

Occult Review V12 N2 Aug 1910

AUGUST 1910. SEVENPENCE NET. IheQCCULT LREYIEW EDITED B Y RäIPH SHIRLEY C ontents NOTES OF THE MONTH By the Editor PASCAL By Bernard O’Neill THE HEALING-CUP OF NANTEOS By M. L. Lewes THE SEERESS OF PREVORST By F. Leonard DREAMS By Nadine de Grancy THE PHILOSOPHER’S STONE By Franz Hartmann, M.D. CORRESPONDENCE PERIODICAL LITERATURE REVIEWS T c LONDON : WILLIAM RIDER AND SON. LTD. 164 ALDERSGATE STREET, E.C. UNITED STATES»! ARTS.UK DELAPIERKE, 19 WARREN STREET. NEW YORK; THE INTERNATIONAL NEWS COMPANY, 85 DUANE STREET, NEW YORK j NEW ENGLAND NEWS COMPANY, BOSTON: WESTERN NEWS COMPANY. CHICAOO. AUSTRALASIA AND SOUITI AFRICA: GORDON AND OOTCH. CAPE TOWN: DAWSON AND SONS, Lid . INDIA: A. H. WHEELER AND CO. "zrl 11 a']' inni! 124, VICTORIA STREET, S.W. T e l . : 3 2 1 0 V I C T O R I A . THE EQUINOX. ACH ^number of this illustrated review contains over 400 pages. E Besides containing many poems, essays and stories of occult interest, it is devoted to an exposition of the principles of Scientific Illuminism ; i.e., the application of critical scientific methods to the processes of self development. It is also the Official Organ of the A.•.A/. Among their official publications in The Equinox will be found :— (t) An Account of the A.'. A.\ Historical. (2} Liber Librae. Ethical. (3) Liber E. Practical. Elementary practices toward gaining control of the body and the mind. (4 Liber 0. Practical. Instruction in travelling in the Spirit Vision, rising on the planes, etc. With the rituals of the Pentagram and Hexagram, the Vibration of Divine Names and other methods of protection and development. -

This Is Wales. 02–03 This Is Wales Wales

2017 visitwales.com This is Wales. 02–03 This is Wales Wales. visitwales.com Year of Legends 2017 04–37 38–81 82–91 This is Wales. Travel Handbook. Useful Information. This is Wales. In 2017 we’re celebrating our epic But where to begin? To get you started, By this point in the magazine you’re past, present and future like never here are 20 places to visit in Wales in completely sold on Wales, right? 04 Land of Legends before, with attractions, events 2017. Think of it as a taster-menu of So you’re going to need some advice 08 Epic Thinking and activities at legendary locations towns and cities, and their surrounding on how to get here and finding your 12 Major Events across Wales. We’re immersing visitors areas, ranging from the wonderful Isle way around. Here’s all the essential 14 Castle Country in our epic story, and making new of Anglesey to the buzz and bustle info about our 13 distinct holiday areas, 16 Coast legendary experiences. This is our of Cardiff, Europe’s youngest capital travelling to / around Wales, and how 20 Time Travel Year of Legends. And while we’re city. In between, there’s enough coast, to make sure you’re booking the best 24 Big Country a land of castles and King Arthur, countryside and mountain to keep you accommodation. We’ll give you a crash 28 Food & Drink we’re also pretty nifty at high adventure exploring for... well, forever. course in our lovely Welsh language, 32 Events Diary and global events.