The Arctic Coal Rush

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen U Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80°

distinguished travel for more than 35 years Voyage UNDER THE Midnight Sun Arctic Expedition12° 16° 20° 24° 28° 32° Spitsbergen u Svalbard Archipelago 80° 80° 80° Raudfjorden Nordaustlandet Woodfjorden Smeerenburg Monaco Glacier The Arctic’s 79° 79° 79° Kongsfjorden Svalbard King’s Glacier Archipelago Ny-Ålesund Spitsbergen Longyearbyen Canada 78° 78° 78° i Greenland tic C rcle rc Sea Camp Millar A U.S. North Pole Russia Bellsund Calypsobyen Svalbard Archipelago Norway Copenhagen Burgerbukta 77° 77° 77° Cruise Itinerary Denmark Air Routing Samarin Glacier Hornsund Barents Sea June 20 to 30, 2022 4° 8° Spitsbergen12° u Samarin16° Glacier20° u Calypsobyen24° 76° 28° 32° 36° 76° Voyage across the Arctic Circle on this unique 11-day Monaco Glacier u Smeerenburg u Ny-Ålesund itinerary featuring a seven-night cruise round trip Copenhagen 1 Depart the U.S. or Canada aboard the Five-Star Le Boréal. Visit during the most 2 Arrive in Copenhagen, Denmark enchanting season, when the region is bathed in the magical 3 Copenhagen/Fly to Longyearbyen, Spitsbergen, light of the Midnight Sun. Cruise the shores of secluded Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago/Embark Le Boréal 4 Hornsund for Burgerbukta/Samarin Glacier Spitsbergen—the jewel of Norway’s rarely visited Svalbard 5 Bellsund for Calypsobyen/Camp Millar archipelago enjoy expert-led Zodiac excursions through 6 Cruising the Arctic Ice Pack sandstone mountain ranges, verdant tundra and awe-inspiring 7 MåkeØyane/Woodfjorden/Monaco Glacier ice formations. See glaciers calve in luminous blues and search 8 Raudfjorden for Smeerenburg for Arctic wildlife, including the “King of the Arctic,” the 9 Ny-Ålesund/Kongsfjorden for King’s Glacier polar bear, whales, walruses and Svalbard reindeer. -

Handbok07.Pdf

- . - - - . -. � ..;/, AGE MILL.YEAR$ ;YE basalt �- OUATERNARY votcanoes CENOZOIC \....t TERTIARY ·· basalt/// 65 CRETACEOUS -� 145 MESOZOIC JURASSIC " 210 � TRIAS SIC 245 " PERMIAN 290 CARBONIFEROUS /I/ Å 360 \....t DEVONIAN � PALEOZOIC � 410 SILURIAN 440 /I/ ranite � ORDOVICIAN T 510 z CAM BRIAN � w :::;: 570 w UPPER (J) PROTEROZOIC � c( " 1000 Ill /// PRECAMBRIAN MIDDLE AND LOWER PROTEROZOIC I /// 2500 ARCHEAN /(/folding \....tfaulting x metamorphism '- subduction POLARHÅNDBOK NO. 7 AUDUN HJELLE GEOLOGY.OF SVALBARD OSLO 1993 Photographs contributed by the following: Dallmann, Winfried: Figs. 12, 21, 24, 25, 31, 33, 35, 48 Heintz, Natascha: Figs. 15, 59 Hisdal, Vidar: Figs. 40, 42, 47, 49 Hjelle, Audun: Figs. 3, 10, 11, 18 , 23, 28, 29, 30, 32, 36, 43, 45, 46, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 71, 72, 75 Larsen, Geir B.: Fig. 70 Lytskjold, Bjørn: Fig. 38 Nøttvedt, Arvid: Fig. 34 Paleontologisk Museum, Oslo: Figs. 5, 9 Salvigsen, Otto: Figs. 13, 59 Skogen, Erik: Fig. 39 Store Norske Spitsbergen Kulkompani (SNSK): Fig. 26 © Norsk Polarinstitutt, Middelthuns gate 29, 0301 Oslo English translation: Richard Binns Editor of text and illustrations: Annemor Brekke Graphic design: Vidar Grimshei Omslagsfoto: Erik Skogen Graphic production: Grimshei Grafiske, Lørenskog ISBN 82-7666-057-6 Printed September 1993 CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................6 The Kongsfjorden area ....... ..........97 Smeerenburgfjorden - Magdalene- INTRODUCTION ..... .. .... ....... ........ ....6 fjorden - Liefdefjorden................ 109 Woodfjorden - Bockfjorden........ 116 THE GEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF SVALBARD .... ........... ....... .......... ..9 NORTHEASTERN SPITSBERGEN AND NORDAUSTLANDET ........... 123 SVALBARD, PART OF THE Ny Friesland and Olav V Land .. .123 NORTHERN POLAR REGION ...... ... 11 Nordaustlandet and the neigh- bouring islands........................... 126 WHA T TOOK PLACE IN SVALBARD - WHEN? .... -

Geographic Board Games

GSR_3 Geospatial Science Research 3. School of Mathematical and Geospatial Science, RMIT University December 2014 Geographic Board Games Brian Quinn and William Cartwright School of Mathematical and Geospatial Sciences RMIT University, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract Geographic Board Games feature maps. As board games developed during the Early Modern Period, 1450 to 1750/1850, the maps that were utilised reflected the contemporary knowledge of the Earth and the cartography and surveying technologies at their time of manufacture and sale. As ephemera of family life, many board games have not survived, but those that do reveal an entertaining way of learning about the geography, exploration and politics of the world. This paper provides an introduction to four Early Modern Period geographical board games and analyses how changes through time reflect the ebb and flow of national and imperial ambitions. The portrayal of Australia in three of the games is examined. Keywords: maps, board games, Early Modern Period, Australia Introduction In this selection of geographic board games, maps are paramount. The games themselves tend to feature a throw of the dice and moves on a set path. Obstacles and hazards often affect how quickly a player gets to the finish and in a competitive situation whether one wins, or not. The board games examined in this paper were made and played in the Early Modern Period which according to Stearns (2012) dates from 1450 to 1750/18501. In this period printing gradually improved and books and journals became more available, at least to the well-off. Science developed using experimental techniques and real world observation; relying less on classical authority. -

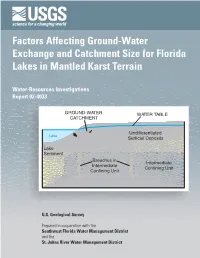

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain

Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 GROUND-WATER WATER TABLE CATCHMENT Undifferentiated Lake Surficial Deposits Lake Sediment Breaches in Intermediate Intermediate Confining Unit Confining Unit U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and the St. Johns River Water Management District Factors Affecting Ground-Water Exchange and Catchment Size for Florida Lakes in Mantled Karst Terrain By T.M. Lee U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4033 Prepared in cooperation with the SOUTHWEST FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT and the ST. JOHNS RIVER WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Tallahassee, Florida 2002 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director The use of firm, trade, and brand names in this report is for identification purposes only and does not constitute endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. For additional information Copies of this report can be write to: purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Suite 3015 Box 25286 227 N. Bronough Street Denver, CO 80225-0286 Tallahassee, FL 32301 888-ASK-USGS Additional information about water resources in Florida is available on the World Wide Web at http://fl.water.usgs.gov CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Climate in Svalbard 2100

M-1242 | 2018 Climate in Svalbard 2100 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation NCCS report no. 1/2019 Photo: Ketil Isaksen, MET Norway Editors I.Hanssen-Bauer, E.J.Førland, H.Hisdal, S.Mayer, A.B.Sandø, A.Sorteberg CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 CLIMATE IN SVALBARD 2100 Commissioned by Title: Date Climate in Svalbard 2100 January 2019 – a knowledge base for climate adaptation ISSN nr. Rapport nr. 2387-3027 1/2019 Authors Classification Editors: I.Hanssen-Bauer1,12, E.J.Førland1,12, H.Hisdal2,12, Free S.Mayer3,12,13, A.B.Sandø5,13, A.Sorteberg4,13 Clients Authors: M.Adakudlu3,13, J.Andresen2, J.Bakke4,13, S.Beldring2,12, R.Benestad1, W. Bilt4,13, J.Bogen2, C.Borstad6, Norwegian Environment Agency (Miljødirektoratet) K.Breili9, Ø.Breivik1,4, K.Y.Børsheim5,13, H.H.Christiansen6, A.Dobler1, R.Engeset2, R.Frauenfelder7, S.Gerland10, H.M.Gjelten1, J.Gundersen2, K.Isaksen1,12, C.Jaedicke7, H.Kierulf9, J.Kohler10, H.Li2,12, J.Lutz1,12, K.Melvold2,12, Client’s reference 1,12 4,6 2,12 5,8,13 A.Mezghani , F.Nilsen , I.B.Nilsen , J.E.Ø.Nilsen , http://www.miljodirektoratet.no/M1242 O. Pavlova10, O.Ravndal9, B.Risebrobakken3,13, T.Saloranta2, S.Sandven6,8,13, T.V.Schuler6,11, M.J.R.Simpson9, M.Skogen5,13, L.H.Smedsrud4,6,13, M.Sund2, D. Vikhamar-Schuler1,2,12, S.Westermann11, W.K.Wong2,12 Affiliations: See Acknowledgements! Abstract The Norwegian Centre for Climate Services (NCCS) is collaboration between the Norwegian Meteorological In- This report was commissioned by the Norwegian Environment Agency in order to provide basic information for use stitute, the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate, Norwegian Research Centre and the Bjerknes in climate change adaptation in Svalbard. -

Thylacinidae

FAUNA of AUSTRALIA 20. THYLACINIDAE JOAN M. DIXON 1 Thylacine–Thylacinus cynocephalus [F. Knight/ANPWS] 20. THYLACINIDAE DEFINITION AND GENERAL DESCRIPTION The single member of the family Thylacinidae, Thylacinus cynocephalus, known as the Thylacine, Tasmanian Tiger or Wolf, is a large carnivorous marsupial (Fig. 20.1). Generally sandy yellow in colour, it has 15 to 20 distinct transverse dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. While the large head is reminiscent of the dog and wolf, the tail is long and characteristically stiff and the legs are relatively short. Body hair is dense, short and soft, up to 15 mm in length. Body proportions are similar to those of the Tasmanian Devil, Sarcophilus harrisii, the Eastern Quoll, Dasyurus viverrinus and the Tiger Quoll, Dasyurus maculatus. The Thylacine is digitigrade. There are five digital pads on the forefoot and four on the hind foot. Figure 20.1 Thylacine, side view of the whole animal. (© ABRS)[D. Kirshner] The face is fox-like in young animals, wolf- or dog-like in adults. Hairs on the cheeks, above the eyes and base of the ears are whitish-brown. Facial vibrissae are relatively shorter, finer and fewer than in Tasmanian Devils and Quolls. The short ears are about 80 mm long, erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Sexual dimorphism occurs, adult males being larger on average. Jaws are long and powerful and the teeth number 46. In the vertebral column there are only two sacrals instead of the usual three and from 23 to 25 caudal vertebrae rather than 20 to 21. -

Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa

Hydrogeology and Simulation of Ground- Water Flow in the Silurian-Devonian Aquifer System, Johnson County, Iowa By Patrick Tucci (U.S. Geological Survey) and Robert M. McKay (Iowa Department of Natural Resources, Iowa Geological Survey) Prepared in cooperation with The Iowa Department of Natural Resources – Water Supply Bureau City of Iowa City Johnson County Board of Supervisors City of Coralville The University of Iowa City of North Liberty City of Solon Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5266 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2006 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Tucci, Patrick and McKay, Robert, 2006, Hydrogeology and simulation of ground-water flow in the Silurian-Devonian aquifer system, Johnson County, Iowa: U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations -

Aedes Press Release Snøhetta Arctic Nordic Alpine EN

Press Release Snøhetta Arctic Nordic Alpine – In Dialogue With Landscape In cooperation with Zumtobel and AW Architektur & Wohnen New Tungestølen Tourist Cabin in Luster, Norway © Jan M. Lillebø Exhibition: 4 July - 20 August 2020, no public opening ceremony Venue: Aedes Architecture Forum, Christinenstr. 18-19, 10119 Berlin Opening hours: Tue-Fri 11am-6.30pm, Sun-Mon 1-5pm and Sat, 4 July 2020, 1-5pm Arctic Nordic Alpine is dedicated to contemporary architecture in vulnerable landscapes, focussing on the influence interventions could have on regions with extreme climatic conditions. The exhibition presents pioneering projects by the internationally renowned architecture and design firm Snøhetta, including the energy-efficient Hotel Svart in Svartisen, the Arctic World Archive Visitor Center in Svalbard Island and the Museum Quarter in Bolzano. These buildings illustrate that architecture can make a significant contribution to the mitigation of climate change by promoting a more sustainable use of nature with innovative strategies and solutions – in dialogue with landscape. Conceived and designed by Snøhetta, also including proposals from students, the exhibition is shown at Aedes in cooperation with Zumtobel Lighting and AW Architektur & Wohnen magazine. On this occasion, Snøhetta is honoured with the prestigious AW Architect of the Year 2020 award. AW Architect of the Year 2020 for Snøhetta For the ninth time, AW Architektur & Wohnen is awarding the AW Architect of the Year. With this prize, the editorial staff honours offices that give new impetus to architecture through individual concepts and original design ideas. Previous winners include MVRDV, UNStudio, BIG and Dorte Mandrup. This year, the Norwegian firm Snøhetta “receives the award for its approach to thinking architecture in an interdisciplinary way, designing it as a special meeting place, understanding it as part of the surrounding landscape – and interpreting buildings themselves as landscape“, explains Jörn Kengelbach, editor-in-chief of AW Architektur & Wohnen. -

VAN DIEMEN's LAND COMPANY Records, 1824-1930 Reels M337

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT VAN DIEMEN’S LAND COMPANY Records, 1824-1930 Reels M337-64, M585-89 Van Diemen’s Land Company 35 Copthall Avenue London EC2 National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1960-61, 1964 CONTENTS Page 3 Historical note M337-64 4 Minutes of Court of Directors, 1824-1904 4 Outward letter books, 1825-1902 6 Inward letters and despatches, 1833-99 9 Letter books (Van Diemen’s Land), 1826-48 11 Miscellaneous papers, 1825-1915 14 Maps, plan and drawings, 1827-32 14 Annual reports, 1854-1922 M585-89 15 Legal documents, 1825-77 15 Accounts, 1833-55 16 Tasmanian letter books, 1848-59 17 Conveyances, 1851-1930 18 Miscellaneous papers 18 Index to despatches 2 HISTORICAL NOTE In 1824 a group of woollen mill owners, wool merchants, bankers and investors met in London to consider establishing a land company in Van Diemen’s Land similar to the Australian Agricultural Company in New South Wales. Encouraged by the support of William Sorell, the former Lieutenant- Governor, and Edward Curr, who had recently returned from the colony, they formed the Van Diemen’s Land Company and applied to Lord Bathurst for a grant of 500,000 acres. Bathurst agreed to a grant of 250,000 acres. The Van Diemen’s Land Company received a royal charter in 1825 giving it the right to cultivate land, build roads and bridges, lend money to colonists, execute public works, and build and buy houses, wharves and other buildings. Curr was appointed the chief agent of the Company in Van Diemen’s Land. -

Outline Tourist-Research Chapter

1 Tourists and Researcher identities: critical considerations of collisions, collaborations and confluences in Svalbard Pre-print copy. Feb 2018. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by the Taylor and Francis Group in The Journal of Sustainable Tourism on 25/02/2018, Please cite as Saville, Samantha M. 2018. ‘Tourists and Researcher Identities: Critical Considerations of Collisions, Collaborations and Confluences in Svalbard’. Journal of Sustainable Tourism https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1435670. Abstract Svalbard is an ‘edge-of-the-world’ hot spot for environmental change, political discourse, tourism and scientific research in the Anthropocene. Drawing on ethnographic and qualitative research, I use this context to critically explore the identity-categories of ‘researcher’ and ‘tourist’. Through the lens of political ecology, I draw out the uneven power relations of knowledge production that are attached to these labels and their consequences for ongoing efforts for managing sustainable tourism. By considering the experiences of tourists, researchers and ‘scientific tourists’ both practically and from an embodied experiential perspective, I challenge the distinctions typically made between these roles. I bring to light several common aspects, goals and experiences these practices share. In doing so I aim to disrupt the existing hierarchies of knowledge that champion an impersonal, rational scientific approach and call for a more varied array of knowledges and practices to be taken into account when considering the future ecologies of Svalbard and the broader Arctic region. Key Words: Identity; knowledge production; political ecology; Anthropocene; Svalbard. S.M. Saville (2018) 1 2 Introduction “It is a not uninformative conceit to play with the scandalous suggestion that ethnographer and tourist are, if not the same creature then the same species and are part of the same continuum – that homo academicus might be uncomfortably closely related to that embarrassing relative turistas vulgaris” (Crang 2011, 207). -

Erik the Red's Land

In May this year, a Briton named Alex Hartley gamely claimed as his personal territory a tiny island in Sval- bard that had been revealed by retreating ice. Sval bard’s islands have a long history of claims and counter-claims by adventurers of diverse nations: the question of who owns the Arctic is an old one. In this next article in our unreviewed biographical/historical series, Frode Skarstein describes Norway’s bid to wrest a corner of Greenland from the Danish crown 75 years ago. Erik the Red’s Land: the land that never was Frode Skarstein Norwegian Polar Institute, Polar Environmental Centre, NO-9296 Tromsø, Norway, [email protected]. “Saturday, 27th of June, 1931. Eventful day. A long coded telegram late last night that I deciphered during the night. At fi ve pm we hoisted the fl ag and occupied the land from Calsbergfjord to Besselsfjord. It will be exciting to see how it develops.” (Devold 1931: author’s translation.) Although not as pithy as the Unity’s log entry from 1616—“Cape Hoorn in 57° 48' S. Rounded 8 p.m.”—when the southern tip of the Americas was fi rst rounded (Hough 1971), the above diary entry by Hallvard Devold is still a salient understatement given the context in which it was made. The next day Devold sent the following telegram to a select few Norwegian newspapers: “In the presence of Eiliv Herdal, Tor Halle, Ingvald Strøm and Søren Rich- ter, the Norwegian fl ag has been hoisted today in Myggbukta. And the land between Carls berg fjord to the south and Bessel fjord to the north occupied in His Pawns in their game: Devold (left) and fellow expe di tion mem bers during the Majesty King Haakon’s name. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com.