Alles Zusammen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Development (2-Downloads)

The Developed and Developing World Income GNI per capita, World Bank Atlas method, 2007 Greenland (Den) Low-income countries ($935 or less) Faeroe Lower-middle-income countries ($936–$3,705) Islands Iceland (Den) Upper-middle-income countries ($3,706–$11,455) Norw High-income countries ($11,456 or more) The Netherlands Canada United Kingdom no data Isle of Man (UK) Denm Ireland Ge Channel Islands (UK) Belgium Luxembourg France Switzerl I Liechtenstein Andorra Spain United States Monaco Portugal Bermuda Gibraltar (UK) (UK) Tu British Virgin Islands (UK) Middle East & North Africa Morocco The Bahamas Algeria Mexico Dominican $2,794 Former Republic Spanish Cayman Islands (UK) Puerto Sahara Cuba Rico (US) US Virgin St. Kitts and Nevis Islands (US) Antigua and Barbuda Mauritania Belize Jamaica Haiti Cape Verde Guadeloupe (Fr) Mali N Guatemala Honduras Aruba Dominica Senegal Martinique (Fr) El Salvador (Neth) St. Lucia The Gambia Nicaragua Barbados Guinea-Bissau Burkina Faso Guinea Panama Benin Costa Rica Trinidad St. Vincent and the Grenadines Niger and Tobago Grenada Sierra Leone Côte Ghana d'Ivoire Netherlands R.B. de French Guiana Liberia Ca Antilles (Neth) Venezuela Guyana (Fr) Togo Colombia Equato Kiribati Latin America & Caribbean Suriname São Tomé and Príncipe Ecuador $5,540 Peru Brazil French Polynesia (Fr) Bolivia Brazil Paraguay $5,910 Uruguay Chile Argentina Source: Data from Atlas of Global Development, 2nd ed., pp. 10–11. © Collins Bartholomew Ltd., 2010. Russian Federation Europe & Central Asia $7,560 $6,051 Sweden way Finland Russian Federation Estonia Latvia nmark Lithuania Czech Republic Belarus Slovak Republic Poland ermany Slovenia m Croatia Ukraine Kazakhstan Austria Hungary Moldova Serbia rland Romania Bosnia and Herzegovina Mongolia Italy FYR Macedonia Montenegro Bulgaria Uzbekistan Georgia Kyrgyz Republic Albania Azerbaijan Dem. -

P1-13 Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11, 2014 SAFAR 19, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Girls sued Unwelcome The Real Fouz: Prosecutors will for ‘offensive’ dogs find Dos and seek murder social media care at rare don’ts for conviction video, images3 Iran13 shelter healthy37 nails against15 Pistorius Ban on Indian workers Min 09º Max 26º looms as spat escalates High Tide 01:27 & 15.52 Low Tide Meeting to resolve maid guarantee dispute fails 09:08 & 21:03 40 PAGES NO: 16369 150 FILS By Staff Reporter Kuwait Sunil Jain and officials from the for- Delhi in protest against the decision. Filipinos 185,000 and Bangladeshis at eign and interior ministries, during which According to the sources, immigration 180,000. ‘Bomb’ found KUWAIT: A threat to ban the recruitment the issue was discussed at length. departments could start the ban on Indians The Indian embassy has repeatedly of Indian laborers into Kuwait may be Assistant undersecretary for passports from today or from next week unless a com- explained that the bank guarantee is a near ministry implemented as soon as today after a high- and residency Maj Gen Mazen Al-Jarrah promise is reached. Based on the latest offi- decision taken by the Indian government level diplomatic meeting failed to resolve was present at the meeting. Jarrah has cial figures, the number of Indians in Kuwait in 2007 and has been applied in several the dispute over an Indian decision to repeatedly blasted the decision and threat- has rapidly swelled to close to 800,000, countries including all other Gulf states. KUWAIT: A suspected bomb was found near the impose a $2,500 (KD730) bank guarantee ened to impose a ban on Indians. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921 Al-Khatrash, F. A. How to cite: Al-Khatrash, F. A. (1970) British political relation with Kuwait 1890-1921, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9812/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. BRITISH POLITICAL RELATIONS WITH KUWAIT 1890-1921 . by F.A. AL-KHATRASH B.A. 'Ain Shams "Cairo" A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in the University of Durham October 1970 CONTENTS Page Preface i - iii / Chapter One General History of Kuwait from 1890-1899 1 References 32 Chapter Two International Interests in Kuwait 37 References 54 Chapter Three Turkish Relations with Kuwait 1900-1906 57 References 84 J Chapter Four British Political Relations with Kuwait 1904-1921 88 References 131 Conclusion 135 Appendix One Exclusive Agreement: The Kuwaiti sheikh and Britain 23 January 1899 139 Appendix Two British Political Representation in the Persian Gulf 1890-1921 141 Appendix Three United Kingdom*s recognition of Kuwait as an Independent State under British Protection. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Beacon Conference Description and Steering Committee Members………………………………………….3 Community College Sponsors, Other Sponsors…………………………………………………………………………..4 Outstanding Papers Jon Carlson The Balance of Nature and the Hunger of Children: An Ethical Exploration of Genetically Modified Organisms………………………….…….…………………5 Sarah Chan Redefining Beauty Standards: The Negative Influence of the Western Aesthetic of Thinness……………………………………………………….…………..15 Rakesh Chopde ‘Caste-ing’ Call for the Social Network: Leveling the Playing Field in India…………35 Antonio Concolino So What’s the Deal with the Value of the Renminbi Anyway?..............................53 Laura Duran Shakespeare’s Ariel and Caliban: The Others…………………………………………………….63 Erica Espinosa The Good, the Bad, and the Hope: Remittances & Globalization……………….………73 Samuel Han The End of Religion: An Epistemo-personal Exploration……………….……………………90 Adrianne Kirk Medical Miracles: The Price of Creativity? Posthumous Diagnoses of Three Great Artists…………………………………………………………………………………….104 Hannah Knowlton The Irish Potato Famine: Act of Genocide………………………………………………………..122 Diane Lameira Creating the Terrorist: The Psychology of Group Dynamics……………………………..133 1 Ryan McGrail The DeLacey Family; the True Creators of Frankenstein’s Creature………………….149 Joselida Mercado Sowing Wild Oates: Sex, Fairy Tales and Rock and Roll……………………………………157 Siomara Parada Containing the Scourge of AIDS: A Case Study on Brazil…………………………………..164 Theresa Price Kidneys Anyone?.................................................................................................182 -

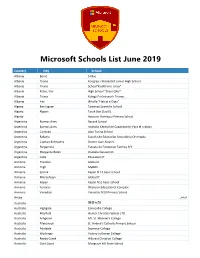

Microsoft Schools List June 2019

Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Albania Berat 5 Maj Albania Tirane Kongresi i Manastirit Junior High School Albania Tirane School"Kushtrimi i Lirise" Albania Patos, Fier High School "Zhani Ciko" Albania Tirana Kolegji Profesional i Tiranës Albania Fier Shkolla "Flatrat e Dijes" Algeria Ben Isguen Tawenza Scientific School Algeria Algiers Tarek Ben Ziad 01 Algeria Azzoune Hamlaoui Primary School Argentina Buenos Aires Bayard School Argentina Buenos Aires Instituto Central de Capacitación Para el Trabajo Argentina Cordoba Alan Turing School Argentina Rafaela Escuela de Educación Secundaria Orientada Argentina Capitan Bermudez Doctor Juan Alvarez Argentina Pergamino Escuela de Educacion Tecnica N°1 Argentina Margarita Belen Graciela Garavento Argentina Caba Educacion IT Armenia Hrazdan Global It Armenia Tegh MyBOX Armenia Syunik Kapan N 13 basic school Armenia Mikroshrjan Global IT Armenia Kapan Kapan N13 basic school Armenia Yerevan Ohanyan Educational Complex Armenia Vanadzor Vanadzor N19 Primary School الرياض Aruba Australia 坦夻易锡 Australia Highgate Concordia College Australia Mayfield Hunter Christian School LTD Australia Ashgrove Mt. St. Michael’s College Australia Ellenbrook St. Helena's Catholic Primary School Australia Adelaide Seymour College Australia Wodonga Victory Lutheran College Australia Reedy Creek Hillcrest Christian College Australia Gold Coast Musgrave Hill State School Microsoft Schools List June 2019 Country City School Australia Plainland Faith Lutheran College Australia Beaumaris Beaumaris North Primary School Australia Roxburgh Park Roxburgh Park Primary School Australia Mooloolaba Mountain Creek State High School Australia Kalamunda Kalamunda Senior High School Australia Tuggerah St. Peter's Catholic College, Tuggerah Lakes Australia Berwick Nossal High School Australia Noarlunga Downs Cardijn College Australia Ocean Grove Bellarine Secondary College Australia Carlingford Cumberland High School Australia Thornlie Thornlie Senior High School Australia Maryborough St. -

Indian Migrant Workers in West Asia Workers In

INDIAN MIGRANT WORKERS IN WEST ASIA Report on a survey of Emigrant workers in UAE and Kuwait (FINAL REPORT) B.A. Prakash Professor, RGIDS RAJIV GANDHI INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES (RGIDS) THIRUVANANTHAPURAM – 695 010 July 2014 Indian Migrant Workers in West Asia Page 1 Preface The Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs, Government of India, has granted financial assistance to set up a Research Programme on International Migration at Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Development Studies (RGIDS), Thiruvananthapuram. The objective is to conduct research relating to various issues and problems of emigration from Kerala as well as India, to organise discussions with emigrants and return emigrants and suggest measures to improve their socio'economic conditions. As part of the Research Programme, RGIDS has conducted a study on return emigration from the West Asia and published its first report during 2013. During the second year, RGIDS conducted a research study on Indian Migrant Workers in UAE and Kuwait and prepared this report. The study has examined the profile of Indian emigrants, employment, wages and working conditions, expenditure, savings and remittances and problems of emigrants in UAE and Kuwait. For collecting primary data, we have conducted a sample survey of 200 Indian emigrant workers in UAE and 165 persons in Kuwait. The study gives an overall situation about the issues and problems of Indian emigrant workers in UAE and Kuwait. Based on the findings of the study, we have given a few recommendations. This research project has been undertaken by Prof. B.A. Prakash, Project Director of the Programme. We are grateful to Shri. -

Foreign Affairs Record VOL XXXVI No 1 January, 1990

1990 January Volume No XXXVI NO 1 1995 CONTENTS Foreign Affairs Record VOL XXXVI No 1 January, 1990 CONTENTS AUSTRALIA Australia for increased Bilateral Cooperation with India in Agriculture 1 BANGLADESH India to Supply Portable Steel Bridges to Bangladesh 1 BELGIUM Belgium to Delink Credit to Specific Proposals 2 CANADA First Ever Seminar-cum-Workshop on Market- ing of Consumer Goods in Canada 2 CYPRUS Indian Tea Launched in Cyprus 4 CZECHOSLOVAKIA Indo-Czech Trade Projected at Rs. 731 crores Trade Protocol for 1990 Signed 4 DANISH Danish Trade Unions Call on Labour Minister 5 EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY India Foregoes EEC Dairy Food Aid 6 FRANCE Joint Communique on Indo-French Coopera- tion in the Field of Water Management 7 Indo-French Cooperation in Civil Aviation and Energy 8 Indo-French Cooperation in Agriculture to Expand to New Areas 8 Indo-French Working Group Meeting on Mineral Exploration 9 Indo-French Cooperation in Food Processing Sector 9 FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY Rs. 95 Crore FRG Grant to India 10 Delhi to Host Ninth Indo-FRG Joint Commis- sion Meet 10 INDONESIA India, Indonesia to Discuss Bilateral Trade 11 MAURITIUS Indo-Mauritian Science and Technology Agree- ment Signed 12 NEPAL Indo-Nepalese Cooperation in Energy and Civil Aviation 12 Joint Press Statement 13 Speech by External Affairs Minister at the Dinner in Honour of the Nepalese Foreign Minister - January 3, 1990 14 OFFICIAL SPOKESMAN'S STATEMENTS Sri Lanka 16 Joint Press Release 16 Pakistan 17 French Prime Minister's Visit to India - 18th-19th January 1990 -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 241 393 AUTHOR TITLE AVAILABLE from EDRS PRICE DESCRIPTORS Zamora, Mario B.; and Others Anthropological Diplo

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 241 393 SO 015 396 AUTHOR Zamora, Mario b.; And Others TITLE Anthropological Diplomacy: Issues and Principles. Studies in Third World Societies, Publication Number Twenty. /' INSTITUTION College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA. Dept. of Anthropology. PUB DATE Jun 82. NOTE 152p.; For related documents, see ED 229 315 and SO 015 395. AVAILABLE FROMDepartment of Anthropology, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, VA'23185 ($7.00 institutions; $6.00 individuals; $5.00 students). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) -- Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Anthropology; Comparative Analysis; Cross CultUral Studies; Cultural Context; Culture; *Developing Nations; Ethnic Relations; Ethnology; Foreign Countries; Foreign Policy; *International Relations; Language; Policy Formation;' Race IDENTIFIERS Philippines; United States ABSTRACT The focus of this volume is anthropological diplomacy; the promotion of peace and.prevention of war by knowing, f understanding, and appreciating the basic affirmations of society. Eight articles examine the role of race, language, and culture in inter-ethnic and international relations. Vinson Sutlive, Jr. examines the interrelationship of race and culture. Mamitua Saber presents the Philippines.as a case study of the processes of cultural integration. Mario Zamora writes about the cross-cultural themes and values of the Asian aged as migrant's to America. Choong Soon Kim discusses the implications of culture and values for,U.S.* foreign policy ormation, with particular emphasis on relations with Indnd Vietnam. KerKi Fritz relates cultural anthrop9logy to the development of international law, while Lynn Thomas relates anthropology to trendi in international relations. In the final .artiO.e, C. D. -

50 Years of Educational Excellence

50 Years of Educational Excellence His Highness Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah Amir of the State of Kuwait His Highness Sheikh Nawaf His Highness Sheikh Nasser Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah Al-Mohammed Al-Ahmad Al-Sabah Crown Prince Prime Minister 1 50 years of educational excellence... INDIAN COMMUNITY SCHOOL FOUNDERS contents Felicitation Messages .................... 02 – 11 Endowment Fund List .......................... 13 ICSK – a beacon of excellence .....14 – 27 U.C. KOHLI V.M. SHARMA V.V. VARGHESE Students’ Gems ........................... 28 – 34 Alumni Memories .......................... 35 – 41 Chairman’s Vision ........................ 42 – 43 H.S. BAWA S.S. SHARMA K.S. SETHI Principals’ Persuasions ................. 44 – 57 Teachers’ Toots ............................ 58 – 71 Blazing Results ............................. 72 – 79 K.T.B. MENON C.D. MEHTA T.B. MEHTA Kaleidoscope ............................... 80 – 85 What they had to say .................... 86 – 94 The Indian Community School 50 Years of Educational Excellence 4 5 50 Years of Educational Excellence Ajay Malhotra 7 The Indian Community School 50 Years of Educational Excellence Message from Honorary Chairman Board of Trustees Sponsor’s Message……. Ashok Kalra am immensely pleased to address the staff, parents and the children of Indian n the occasion of publishing this Golden Jubilee Memoir, as we look back with I Community School, Kuwait on the grand occasion of the Golden Jubilee Celebration. pride on our glorious past and with hope to our future, it is quite gratifying to note Five decades of dedicated service to the community has enabled the institution to earn Othat the school, which began operations over 50 years ago as the first school for the respect of the community. -

India Speaks (Monthly Digest of Official Indian Statements on Middle East) No

India speaks (Monthly Digest of Official Indian Statements on Middle East) No. 70 May 2015 BILATERAL ISSUES a. EGYPT 1. Sanjay Bhattacharyya appointed as the next Ambassador of India to Arab Republic of Egypt, New Delhi, 17 April 2015 Sanjay Bhattacharyya, (IFS: 1987), presently Joint Secretary in the Ministry of External Affairs, has been appointed as the next Ambassador of India to Arab Republic of Egypt. He is expected to take up his assignment shortly. Source: Ministry of External Affair, New Delhi, http://www.mea.gov.in/press- releases.htm?dtl/25074/Sanjay_Bhattacharyya_appointed_as_the_next_Ambassador_of_India _to_Arab_Republic_of_Egypt b. KUWAIT 2. Emergency Number and the list of Officials who know the regional languages of India, 6 April 2015 The Embassy would like to inform that there is an Emergency number 22530600 during office hours and even beyond normal office hours/weekends. During the office hours, one needs to know the extension number of the concerned Wing which may be dialled immediately after hearing the automatic recorded voice. The extension number of the concerned section/wing is available on the link of 24/7 Emergency contact (Embassy Website). Even if anyone does not know the extension, then caller is attended by the Receptionist who can then connect him/her to the concerned desk. Besides, the Embassy has many officials and local staff who speak the various regional languages whose names are already there on the Embassy Website along with their contact details and mail-IDs. The Embassy has drawn up a list of officials who can be approached for assistance in different Indian languages apart from Hindi and English. -

India and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region: a Bibliography1

India and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region: A Bibliography1 Prepared by Dr. John Calabrese Aafreedi, Navras Jaat (2011). “The Impact of Domestic Politics on India’s Attitudes towards Israel and Jews,” in Priya Singh and Susmita Bhattacharya (Eds.) Perspectives on West Asia: The Evolving Geopolitical Discourses (New Delhi: Shipra). Aaron, Sushil J. (2003). “Straddling Faultlines: India’s Foreign Policy toward the Greater Middle East,” CSH Occasional Paper N°7, Publication of the French Research Institutes in India. Abhyankar, Rajendra M. (2008). “Introduction,” in Rajendra M. Abhyankar (Ed.) West Asia and the Region: Defining India’s Role (New Delhi: Academic Foundation), pp. 27–66. ________________ (Ed.) (2008). West Asia and the Region: Defining India’s Role (New Delhi: Academic Foundation). ________________ (2007). “India’s West Asia Policy: Search for a Middle Ground,” in A. Sinha and M. Mohta (eds). Indian Foreign Policy: Challenges and Opportunities (New Delhi: Academic Foundation), pp. 321–49. Afrasiabi, Kaveh L. (2011). “Nuclear Equation in Iran-India Strategic Relations,” in Anwar Alam (Ed.) India and Iran: An Assessment of Contemporary Relations (New Delhi: New Century Publications). Agha, Qamar (2008). “India’s Economic Diplomacy in the Gulf,” in Rajendra M. Abhyankar (Ed.) West Asia and the Region: Defining India’s Role (New Delhi: Academic Foundation), pp. 139–56. ________________ (2008). “Indo-Arab Relations: The Pakistan Factor” in Anwar Alam (Ed.) India and West Asia in the Era of Globalisation (New Delhi: New Century Publications), pp. 107– 26. Agwani, M.S. (2010). “India and Palestine,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 6:18 (pp. 50–57). ________________ (2009), “Global War on Terrorism,” Journal of Strategic Studies, 5:17 (pp. -

Research on the Effect of Social Networks on the Kuwait Labour Market

Research on the Effect of Social Networks on the Kuwait Labour Market Prepared by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) Joint Programme for the Support of the Public Authority for Manpower Kuwait City, Kuwait May 2016 1 Key Messages: Workers use a range of formal and informal networks that act as social capital for their mobili ty and work trajectory. While networks in home countries play a crucial role in facilitating workers’ move to destination countries, networks with fellow nationals and non- nationals developed during employment abroad are more important in determining their employment trajectories. Large communities of foreign workers in Kuwait (i.e. India) use social networks to sustain their exponential growth through leveraging non-demand driven employment opportunities while smaller communities of foreign workers’ (i.e. Nepal) numbers remain consistent as they tend to use formal recruitment channels to pursue formal demand driven employment opportunities . Institutional factors such as policies of sending and receiving countries may at times amplify the potential negative impact of social networks on labour markets in receiving states. The strength of social capital depends on and reflects not only on the numbers of foreign nationals in the receiving state workforce but also on the level of employment of the workers. Workers who have weaker social capital are likely to face exclusion in the labour market. Workers using social networks to obtain employment opportunities under Visa 20 (domestic workers) and Visa 18 (government projects) are often associated with illegal visa trading. Workers who use social networks to acquire jobs under Visa 18 (shoon) tend to have a mismatch between their skills and the requirement of the jobs.