Idol-Breaking As Image-Making in the 'Islamic State'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Perkins School of Theology

FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF Bridwell Library PERKINS SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 http://www.archive.org/details/historyofperkinsOOgrim A History of the Perkins School of Theology A History of the PERKINS SCHOOL of Theology Lewis Howard Grimes Edited by Roger Loyd Southern Methodist University Press Dallas — Copyright © 1993 by Southern Methodist University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America FIRST EDITION, 1 993 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions Southern Methodist University Press Box 415 Dallas, Texas 75275 Unless otherwise credited, photographs are from the archives of the Perkins School of Theology. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grimes, Lewis Howard, 1915-1989. A history of the Perkins School of Theology / Lewis Howard Grimes, — ist ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87074-346-5 I. Perkins School of Theology—History. 2. Theological seminaries, Methodist—Texas— Dallas— History. 3. Dallas (Tex.) Church history. I. Loyd, Roger. II. Title. BV4070.P47G75 1993 2 207'. 76428 1 —dc20 92-39891 . 1 Contents Preface Roger Loyd ix Introduction William Richey Hogg xi 1 The Birth of a University 1 2. TheEarly Years: 1910-20 13 3. ANewDean, a New Building: 1920-26 27 4. Controversy and Conflict 39 5. The Kilgore Years: 1926-33 51 6. The Hawk Years: 1933-5 63 7. Building the New Quadrangle: 1944-51 81 8. The Cuninggim Years: 1951-60 91 9. The Quadrangle Comes to Life 105 10. The Quillian Years: 1960-69 125 11. -

The Question of 'Race' in the Pre-Colonial Southern Sahara

The Question of ‘Race’ in the Pre-colonial Southern Sahara BRUCE S. HALL One of the principle issues that divide people in the southern margins of the Sahara Desert is the issue of ‘race.’ Each of the countries that share this region, from Mauritania to Sudan, has experienced civil violence with racial overtones since achieving independence from colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s. Today’s crisis in Western Sudan is only the latest example. However, very little academic attention has been paid to the issue of ‘race’ in the region, in large part because southern Saharan racial discourses do not correspond directly to the idea of ‘race’ in the West. For the outsider, local racial distinctions are often difficult to discern because somatic difference is not the only, and certainly not the most important, basis for racial identities. In this article, I focus on the development of pre-colonial ideas about ‘race’ in the Hodh, Azawad, and Niger Bend, which today are in Northern Mali and Western Mauritania. The article examines the evolving relationship between North and West Africans along this Sahelian borderland using the writings of Arab travellers, local chroniclers, as well as several specific documents that address the issue of the legitimacy of enslavement of different West African groups. Using primarily the Arabic writings of the Kunta, a politically ascendant Arab group in the area, the paper explores the extent to which discourses of ‘race’ served growing nomadic power. My argument is that during the nineteenth century, honorable lineages and genealogies came to play an increasingly important role as ideological buttresses to struggles for power amongst nomadic groups and in legitimising domination over sedentary communities. -

CA Students Urge Assembly Members to Pass AB

May 26, 2021 The Honorable Members of the California State Assembly State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Thousands of CA Public School Students Strongly Urge Support for AB 101 Dear Members of the Assembly, We are a coalition of California high school and college students known as Teach Our History California. Made up of the youth organizations Diversify Our Narrative and GENup, we represent 10,000 youth leaders from across the State fighting for change. Our mission is to ensure that students across California high schools have meaningful opportunities to engage with the vast, diverse, and rich histories of people of color; and thus, we are in deep support of AB101 which will require high schools to provide ethnic studies starting in academic year 2025-26 and students to take at least one semester of an A-G approved ethnic studies course to graduate starting in 2029-30. Our original petition made in support of AB331, linked here, was signed by over 26,000 CA students and adult allies in support of passing Ethnic Studies. Please see appended to this letter our letter in support of AB331, which lists the names of all our original petition supporters. We know AB101 has the capacity to have an immense positive impact on student education, but also on student lives as a whole. For many students, our communities continue to be systematically excluded from narratives presented to us in our classrooms. By passing AB101, we can change the precedent of exclusion and allow millions of students to learn the histories of their peoples. -

Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy

TThhee BBooookk ooff EEvvaann:: TThhee wwoorrkk aanndd lliiffee ooff EEvvaann MMccAArraa SShheerrrraarrdd Keith Tudor | Editor E-book edition The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Editor: Keith Tudor E-book (2020) ISBN: 9781877431–88-3 Printed edition (2017) ISBN: 9781877431-78-4 © Keith Tudor 2017, 2020 Keith Tudor asserts his moral right to be known as the Editor of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording, digital or otherwise without the prior written permission of Resource Books Ltd. Waimauku, Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] | www.resourcebooks.co.nz Contents The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Keith Tudor | Editor Contents Foreword. Isabelle Sherrard Poroporoaki: A bridge between two worlds. Haare Williams Introduction to the e-book edition. Keith Tudor Introduction. Keith Tudor The organisation and structure of the book Acknowledgements References Part I. AGRICULTURE Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 1. Papers related to agriculture. Evan M. Sherrard Biology (2008) Film review of The Ground We Won (2015) References Chapter 2. Memories of Evan from Lincoln College and from a farm. Alan Nordmeyer, Robin Plummer, and Colin Wrennall Alan Nordmeyer writes Robin Plummer writes Colin Wrennall writes Part II. MINISTRY Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 3. Sermons. Evan M. Sherrard St. Patrick’s Day (1963) Sickness unto death (1965) Good grief (1966) When things get out of hand (1966) Rains or refugees? (1968) Unconscious influence (n.d.) Faithful winners (1998) Epiphany (2006) Colonialism (2008) Jesus and Paul — The consummate political activists (2009) A modern man faces Pentecost (2010) Ash Wednesday (2011) Healing (2011) Killed by a dancing girl (2012) Self-love (2012) Geering and Feuerbach (2014) Chapter 4. -

DIPBOOK2021.Pdf

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS BRUNEI DARUSSALAM DIPLOMATIC AND CONSULAR LIST 2021 Brunei Darussalam Diplomatic and Consular List 2021 is published by MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS Jalan Subok Bandar Seri Begawan BD2710 Brunei Darussalam Telephone : (673) 2261177 / 1291 / 1292 / 1293 / 1294 / 1295 Fax : (673) 2261740 (Protocol & Consular Affairs Department) Email : [email protected] Website : www.mfa.gov.bn All information is correct as of 18 August 2021 Any amendments can be reported to the Protocol and Consular Affairs Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brunei Darussalam. Email: [email protected] Use QR Code to download an electronic version for this book Printed by Print Plus Sdn Bhd Brunei Darussalam TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................... 4 DIPLOMATIC MISSIONS ................................................................................................ 1 AFGHANISTAN ............................................................................................................... 2 ALGERIA ....................................................................................................................... 3 ANGOLA ........................................................................................................................ 4 ARGENTINA .................................................................................................................. 5 AUSTRALIA .................................................................................................................. -

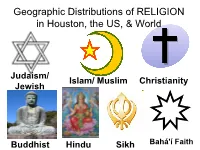

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World Judaism/ Islam/ Muslim Christianity Jewish Buddhist Hindu Sikh Bahá'í Faith Learning Objectives, 109 slides • Overview of religious characteristics • Global and US distribution of religious people; Houston Interfaith Unity Council 3 • General demographic characteristics by religion: income, education 7 • Judaism / Jewish 26 • Islam / Muslims 49 • Hindus 80 • Sikhism 96 • Buddhist 103 Summary of Major Holidays & Celebrations by Religion FLDS Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints polygamy Christianity Christmas, Easter, Lent Buddhist Chinese New Year (lunar calendar) Hindu Holi – festival of colors (youth) Diwali – similar to Christmas Janmashtami – Goddess Lord Krishna (children) Jewish / Judaism Hanukah – similar to Christmas Passover – similar to Easter Rosh Hashanha – Jewish New Year Muslim / Islam Ramadan – month long fast with no food/water in daylight hours EID al Fitr – feast to break the fast Pilgrimage to The Hajj Major Religions of the World Folk Folk Christian Islam Buddhist & Chinese Hindu Christian Judaism Christian (Israel) Christian Sects within Major Religions Orthodox Christian Sunni Buddhist & Chinese Muslim Catholic Judaism (Israel) Orthodox Buddhist & Chinese Sunni Hindu Muslim Shia Muslim Catholic Christian Understanding the distribution of Catholics can help to predict location of the new Pope. Non-Religious % There are many parallels between religion and other social variables, in this case wealth and religiosity. more religious less religious Greater wealth -

JGI V. 14, N. 2

Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective Volume 14 Number 2 Multicultural Morocco Article 1 11-15-2019 Full Issue - JGI v. 14, n. 2 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation (2019) "Full Issue - JGI v. 14, n. 2," Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/jgi/vol14/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multicultural Morocco JOURNAL of GLOBAL INITIATIVES POLICY, PEDAGOGY, PERSPECTIVE 2019 VOLUME 14 NUMBER 2 Journal of global Initiatives Vol. 14, No. 2, 2019, pp.1-28. The Year of Morocco: An Introduction Dan Paracka Marking the 35th anniversary of Kennesaw State University’s award-winning Annual Country Study Program, the 2018-19 academic year focused on Morocco and consisted of 22 distinct educational events, with over 1,700 people in attendance. It also featured an interdisciplinary team-taught Year of Morocco (YoM) course that included a study abroad experience to Morocco (March 28-April 7, 2019), an academic conference on “Gender, Identity, and Youth Empowerment in Morocco” (March 15-16, 2019), and this dedicated special issue of the Journal of Global Initiatives. Most events were organized through six different College Spotlights titled: The Taste of Morocco; Experiencing Moroccan Visual Arts; Multiple Literacies in Morocco; Conflict Management, Peacebuilding, and Development Challenges in Morocco, Moroccan Cultural Festival; and Moroccan Solar Tree. -

“The Year According to the Reckoning of the Believers”: Papyrus Louvre Inv. J. David- Weill 20 and the Origins of the Hijrī

Der Islam 2018; 95 (2): 291–311 Mehdy Shaddel* “The Year According to the Reckoning of the Believers”: Papyrus Louvre inv. J. David- Weill 20 and the Origins of the hijrī Era https://doi.org/10.1515/islam-2018-0025 Abstract: The present paper addresses itself to the enigmatic phrase snh qaḍāʾ al-muʾminīn that appears in a papyrus sheet from early Muslim Egypt. It takes issue with the earlier interpretations of the phrase, arguing that it is indeed a dating formula that is probably to be read as sanat qaḍāʾ al-muʾminīn, and under- stood as “the year according to the reckoning of the believers”. Based on the tes- timony of this phrase, it is further argued that the epoch of the Muslim calendar was, in all likelihood, originally meant to count the years from Muḥammad’s foundation of a new community and polity at Medina, a momentous event that the early Muslims conceived of as the dawn of a new age. Keywords: Arabic papyri; Muslim calendar; jurisdiction of the believers; reckon- ing of the believers; hijra; chronology On 24 October, 1793, the Convention Nationale of the fledging First French Repub- lic voted to adopt a new calendar. Thenceforth, the Convention decreed, all offi- cial documents and correspondence had to be dated from the establishment of the republic on 22 September, 1792, using the formula “l’an de la république française”, thereby consigning, as it seemed at the time, the Gregorian calendar to the dustbin of history. An earlier reckoning system that counted the years from the revolution of 1789 employed the formula “l’an de la liberté”. -

2020 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), states that citizens “enjoy freedom of religious belief” but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” without defining “normal.” CCP members and members of the armed forces are required to be atheists and are forbidden from engaging in religious practices. National law prohibits organizations or individuals from interfering with the state educational system for minors younger than the age of 18, effectively barring them from participating in most religious activities or receiving religious education. Some provinces have additional laws on minors’ participation in religious activities. The government continued to assert control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to one of the five state-sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices. -

The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1995 The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco Beebe Bahrami University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ethnic Studies Commons, European History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Bahrami, Beebe, "The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco" (1995). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1176. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1176 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1176 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Persistence of the Andalusian Identity in Rabat, Morocco Abstract This thesis investigates the problem of how an historical identity persists within a community in Rabat, Morocco, that traces its ancestry to Spain. Called Andalusians, these Moroccans are descended from Spanish Muslims who were first forced to convert to Christianity after 1492, and were expelled from the Iberian peninsula in the early seventeenth century. I conducted both ethnographic and historical archival research among Rabati Andalusian families. There are four main reasons for the persistence of the Andalusian identity in spite of the strong acculturative forces of religion, language, and culture in Moroccan society. First, the presence of a strong historical continuity of the Andalusian heritage in North Africa has provided a dominant history into which the exiled communities could integrate themselves. Second, the predominant practice of endogamy, as well as other social practices, reinforces an intergenerational continuity among Rabati Andalusians. Third, the Andalusian identity is a single identity that has a complex range of sociocultural contexts in which it is both meaningful and flexible. -

SEVP-Certified Schools in AL, AR, FL, GA, KY, MS, NC, TN, TX, SC, and VA

Student and Exchange Visitor Program U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement FOIA 13-15094 Submitted to SEVP FOIA March 7, 2013 Summary The information presented in the tables below contains the names of SEVP-certified schools located in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, South Carolina and Virginia that have received certification or are currently in the SEVP approval process, between January 1, 2012 -February 28, 2013, to include the date that each school received certification. The summary counts for the schools are as follows: Count of schools School certifications Certification type approved in duration * currently in process * Initial 127 87 Recertification 773 403 (*) In the requested states Initials Approved School Code School Name State Approval Date ATL214F52444000 Glenwood School ALABAMA 1/17/2013 ATL214F52306000 Restoration Academy ALABAMA 11/28/2012 ATL214F51683000 Eastwood Christian School ALABAMA 9/12/2012 ATL214F51988000 Tuscaloosa Christian School ALABAMA 9/11/2012 ATL214F51588000 Bayside Academy ALABAMA 7/27/2012 NOL214F51719000 Bigelow High School ARKANSAS 11/1/2012 NOL214F52150000 Booneville Public Schools ARKANSAS 9/27/2012 NOL214F52461000 Westside High School ARKANSAS 1/22/2013 NOL214F52156000 Charleston High School ARKANSAS 10/22/2012 NOL214F52133000 Atkins Public Schools ARKANSAS 9/19/2012 MIA214F52212000 Barnabas Christian Academy FLORIDA 1/2/2013 MIA214F51178000 The Potter's House Christian Academy FLORIDA 1/10/2012 MIA214F52155000 Conchita Espinosa Academy FLORIDA 11/6/2012 MIA214F52012000 St. Michael Lutheran School FLORIDA 11/14/2012 MIA214F52128000 Calvary Christian Academy FLORIDA 11/16/2012 MIA214F51412000 Hillsborough Baptist School FLORIDA 9/19/2012 MIA214F52018000 Saint Paul's School FLORIDA 10/18/2012 MIA214F52232000 Citrus Park Christian School FLORIDA 12/14/2012 MIA214F52437000 AEF Schools FLORIDA 1/9/2013 MIA214F51721000 Electrolysis Institute of Tampa, Inc. -

Caliphal Imperialism and Ḥijāzī Elites in the Second/Eighth Century

This is a repository copy of Caliphal Imperialism and Ḥijāzī Elites in the Second/Eighth Century. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/98416/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Munt, Thomas Henry Robert orcid.org/0000-0002-6385-1406 (2016) Caliphal Imperialism and Ḥijāzī Elites in the Second/Eighth Century. Al-Masāq : Islam and the Medieval Mediterranean. pp. 6-21. ISSN 1473-348X https://doi.org/10.1080/09503110.2016.1153296 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Caliphal imperialism and Ḥijāzī elites in the second/eighth century Harry Munt University of York In 129/747, during the reign of the last Umayyad caliph Marwān b. Muḥammad (r. 127– 132/744–749), a Kharijite rebel called Abū Ḥamza al-Mukhtār b. ʿAwf advanced on Mecca during the hajj season. The Umayyad governor, ʿAbd al-Wāḥid b. Sulaymān, abandoned both the town and the pilgrims.