Bleeding Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 8: Hematology CHAPTER 47: ANEMIA

Section 8: Hematology CHAPTER 47: ANEMIA Q.1. A 56-year-old man presents with symptoms of severe dyspnea on exertion and fatigue. His laboratory values are as follows: Hemoglobin 6.0 g/dL (normal: 12–15 g/dL) Hematocrit 18% (normal: 36%–46%) RBC count 2 million/L (normal: 4–5.2 million/L) Reticulocyte count 3% (normal: 0.5%–1.5%) Which of the following caused this man’s anemia? A. Decreased red cell production B. Increased red cell destruction C. Acute blood loss (hemorrhage) D. There is insufficient information to make a determination Answer: A. This man presents with anemia and an elevated reticulocyte count which seems to suggest a hemolytic process. His reticulocyte count, however, has not been corrected for the degree of anemia he displays. This can be done by calculating his corrected reticulocyte count ([3% × (18%/45%)] = 1.2%), which is less than 2 and thus suggestive of a hypoproliferative process (decreased red cell production). Q.2. A 25-year-old man with pancytopenia undergoes bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, which reveals profound hypocellularity and virtual absence of hematopoietic cells. Cytogenetic analysis of the bone marrow does not reveal any abnormalities. Despite red blood cell and platelet transfusions, his pancytopenia worsens. Histocompatibility testing of his only sister fails to reveal a match. What would be the most appropriate course of therapy? A. Antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine, and prednisone B. Prednisone alone C. Supportive therapy with chronic blood and platelet transfusions only D. Methotrexate and prednisone E. Bone marrow transplant Answer: A. Although supportive care with transfusions is necessary for treating this patient with aplastic anemia, most cases are not self-limited. -

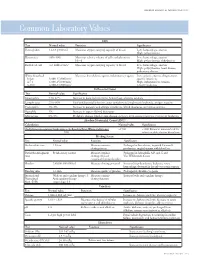

Common Laboratory Values

AmericAn AcAdemy of PediAtric dentistry Reference Manual 2006-2007 Resource Section 251 Common LaboratoryCommon Values Laboratory Values CBC Test Normal value Function Significance Hemoglobin 12-18 g/100 mL Measures oxygen carrying capacity of blood Low: hemorrhage, anemia High: polycythemia Hematocrit 35%-50% Measures relative volume of cells and plasma in Low: hemorrhage, anemia blood High: polycythemia, dehydration Red blood cell 4-6 million/mm3 Measures oxygen-carrying capacity of blood Low: hemorrhage, anemia High: polycythemia, heart disease, pulmonary disease White blood cell Measures host defense against inflammatory agents Low: aplastic anemia, drug toxicity, Infant 8,000-15,000/mm3 specific infections 4-7 y 6,000-15,000/mm3 High: inflammation, trauma, 8-18 y 4,500-13,500/mm3 toxicity, leukemia Differential Count Test Normal value Significance Neutrophils 54%-62% Increase in bacterial infections, hemorrhage, diabetic acidosis Lymphocytes 25%-30% Viral and bacterial infection, acute and chronic lymphocytic leukemia, antigen reaction Eosinophils 1%-3% Increase in parasitic and allergic conditions, blood dyscrasias, pernicious anemia Basophils 1% Increase in types of blood dyscrasias Monocytes 0%-9% Hodgkin’s disease, lipid storage disease, recovery from severe infections, monocytic leukemia Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) Calculation Normal value Significance (% Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes + % Bands)×Total White Cell Count >1500 <1000 Patient at increased risk for 100 infection; defer elective dental care Bleeding Screen Test -

Prolonged Partial Thromboplastin Time Without Bleeding History; Fletcher Factor Deficiency

Prolonged Partial Thromboplastin Time Without Bleeding History; Fletcher Factor Deficiency Celalettin ÜSTÜN*, Anand JILLELLA*, Linda HENDRIKS*, Mary JONAH**, Ferdane KUTLAR*, Russell BURGESS*, Abdullah KUTLAR* * Section of Hematology Oncology, Department of Medicine, Medical College of Georgia, ** Department of Pathology, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, USA ABSTRACT A 67-year-old patient was admitted to the hospital to perform an esophagogastrectomy because a lesion at the lower esophagus was strongly suspicious for cancer. Her medical history and her family his- tory were negative for bleeding tendency or thrombosis. Her activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was prolonged (44 s) whereas her prothrombin time (PT) was normal (11 s) presurgery. Mixing of her plasma with normal plasma corrected her prolonged aPTT (27.9 s). Prolonged incubation shortened the patient’s aPTT (36.3 s). Fletcher factor activity was found to be 50%. The patient underwent an esopha- gogastrectomy without bleeding complications under spinal anesthesia. Fletcher factor deficiency, a ra- re disorder, should be considered in patients who have no history of bleeding tendency with a prolonged aPTT. Surgical interventions are safe in these patients. Key Words: aPTT, Surgery, Fletcher factor, Prekallikrein. Turk J Haematol 2002;19(3): 417-419 Received: 20.06.2001 Accepted: 28.07.2001 INTRODUCTION unt[2]. Hematologists are frequently consulted for preoperative coagulation abnormalities. Preoperative evaluation of hemostasis is cru- cial to assess the risk of per-and peri-operative Prolonged aPTT is not an uncommon abnor- bleeding. The most effective screening method is mality encountered during preoperative evaluati- to obtain a thorough history of bleeding[1]. on. It may indicate the presence of antiphospholi- Preoperative screening tests mostly include acti- pid antibodies or a factor deficiency in the intrinsic vated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), proth- and/or common pathways of blood coagulation. -

The Preoperative Bleeding Time Test: Assessing Its Clinical Usefulness

The preoperative bleeding time test: assessing its clinical usefulness AMY S. GEWIRTZ, MD; KANDICE KOTTKE-MARCHANT MD, PHD; MICHAEL L. MILLER, DO HE BLEEDING TIME is the The bleeding time test can aid in the diagnostic most commonly used evaluation of patients with clinical hemorrhagic disorders or test in the in vivo evalu- a history of bleeding. However, its low positive predictive ation of primary hemo- value in predicting perioperative bleeding should force one to T stasis. Although this test is known abandon it as a routine preoperative screening test. for its role in the evaluation of pa- tients suspected of having von INa'iiV Ji J Many methodologic factors affect the bleeding Willebrand's disease or abnormal time, including the length, depth, orientation, and location platelet function, it is quite often of the incision and whether a blood pressure cuff is used. The routinely ordered as part of preop- bleeding time also varies with age, sex, blood group, medica- erative screening to predict periop- tion use, skin characteristics, and diet. A prolonged bleed- erative bleeding in patients with ing time itself is nonspecific and is not pathognomonic of a no previous clinical signs of a single disease entity. Many studies have shown no associa- bleeding disorder. Physicians tion between a prolonged preoperative bleeding time and in- should be familiar with factors that creased perioperative blood loss. Even though a prolonged affect the standardization, reliabil- preoperative bleeding time usually lacks clinical significance, ity and specificity of the bleeding it often leads to additional laboratory tests, postponement of time test, as well as the pitfalls of surgery, increased length of stay, and possibly inappropriate using it to predict clinically signifi- treatment. -

Circular of Information for the Use of Human Blood and Blood Components

CIRCULAR OF INFORMATION FOR THE USE OF HUMAN BLOOD Y AND BLOOD COMPONENTS This Circular was prepared jointly by AABB, the AmericanP Red Cross, America’s Blood Centers, and the Armed Ser- vices Blood Program. The Food and Drug Administration recognizes this Circular of Information as an acceptable extension of container labels. CO OT N O Federal Law prohibits dispensing the blood and blood compo- nents describedD in this circular without a prescription. THIS DOCUMENT IS POSTED AT THE REQUEST OF FDA TO PROVIDE A PUBLIC RECORD OF THE CONTENT IN THE OCTOBER 2017 CIRCULAR OF INFORMATION. THIS DOCUMENT IS INTENDED AS A REFERENCE AND PROVIDES: Y • GENERAL INFORMATION ON WHOLE BLOOD AND BLOOD COMPONENTS • INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE • SIDE EFFECTS AND HAZARDS P THIS DOCUMENT DOES NOT SERVE AS AN EXTENSION OF LABELING REQUIRED BY FDA REGUALTIONS AT 21 CFR 606.122. REFER TO THE CIRCULAR OF INFORMATIONO WEB- PAGE AND THE DECEMBER 2O17 FDA GUIDANCE FOR IMPORTANT INFORMATION ON THE CIRCULAR. C T O N O D Table of Contents Notice to All Users . 1 General Information for Whole Blood and All Blood Components . 1 Donors . 1 Y Testing of Donor Blood . 2 Blood and Component Labeling . 3 Instructions for Use . 4 Side Effects and Hazards for Whole Blood and P All Blood Components . 5 Immunologic Complications, Immediate. 5 Immunologic Complications, Delayed. 7 Nonimmunologic Complications . 8 Fatal Transfusion Reactions. O. 11 Red Blood Cell Components . 11 Overview . 11 Components Available . 19 Plasma Components . 23 Overview . 23 Fresh Frozen Plasma . .C . 23 Plasma Frozen Within 24 Hours After Phlebotomy . 28 Components Available . -

EDUCATION Four Compartments

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2014; 44:42–5 CME http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2014.110 © 2014 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Coagulation YL Chee Consultant Haematologist, Department of Haematology-Oncology, National University Hospital, Singapore ABSTRACT The haemostatic system comprises four compartments: the vasculature, Correspondence to YL Chee platelets, coagulation factors, and the fibrinolytic system. There is presently no Consultant Haematologist laboratory or near-patient test capable of reproducing the complex regulated Department of Haematology- Oncology interaction between these four compartments. The prothrombin time (PT) and NUHS Tower Block Level 7 activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) only test the coagulation protein 1E Kent Ridge Road compartment of the system and results have to be carefully interpreted in the Singapore 119228 context of the clinical presentation and assay limitations. This article will give a e-mail general overview of the limitations of PT and APTT and discuss specific issues that [email protected] need to be considered when the tests are requested, in the context of anticoagulant monitoring, bleeding symptoms, and routine preoperative screening. Of these indications, routine preoperative screening is the most controversial and is generally not warranted in the absence of an abnormal bleeding history. KEYWORDS Prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin clotting time, preoperative screening, bleeding history, coagulation screen DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION Intrinsic pathway Extrinsic pathway The normal haemostatic system comprises four Factor XII/HMWK*/PK** compartments, the vasculature, platelets, coagulation proteins and the fibrinolytic system. When a blood Factor XI Factor XIa vessel is injured, all four compartments interact in a coordinated manner to prevent blood loss by forming a Factor IX Factor IXa Factor VIIa clot and localising this to the area of injury. -

Coagulation Simplified…

Coagulation Simplified… Published by ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CONTENTS We gratefully acknowledge the support and funding provided by the Ontario Ministry of Health 1. The Basics of Coagulation and Clot Breakdown . 4–7 and Long-Term Care. 2. Routine Coagulation Tests . 8–17 Special thanks to the following people and organizations who provided their expertise in Evaluating coagulation in the laboratory . 8 reviewing the content of this handbook: Sample collection for coagulation testing . 9 Prothrombin Time (PT) . 10 L Gini Bourner (QMP-LS Hematology Committee) International Normalized Ratio (INR) . 11 L Dr. Jeannie Callum Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) . 12 L Dr. Allison Collins Thrombin Time (TT) . 13 Fibrinogen . 14 L Dr. William Geerts D-dimer . 15 L Dr. Alejandro Lazo-Langner Anti-Xa assay . 16 L Dr. Ruth Padmore (QMP-LS Hematology Committee) Summary . 17 L Anne Raby (QMP-LS Hematology Committee) 3. Anticoagulant Drugs . 18–25 L Dr. Margaret Rand Unfractionated Hepari n (UFH) . 18 L Dr. Alan Tinmouth Low Molecular Weight Heparins (LMWHs) . 19 Fondaparinux . 20 Warfarin . 21 Thanks also to: Direct Thrombin Inhibitors (DTI) . 23 L Dale Roddick, photographer, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Direct Xa Inhibitors . 25 L Reena Manohar, graphic artist, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre 4. Evaluating Abnormal Coagulation Tests . 26–29 L The ECAT Foundation Prolonged PT / INR with normal APTT . 26 CLOT-ED Images used or modified with permission from Prolonged APTT with normal PT / INR . 27 the ECAT Foundation, The Netherlands. Prolonged APTT and PT / INR . 28 Prolonged Thrombin Time (TT) with normal or prolonged APTT and PT / INR . 29 March 2013 5. Approach to the Evaluation of the Bleeding Patient . -

Chapter 4 HEMOSTASIS and BLOOD

Chapter 4 HEMOSTASIS AND BLOOD TRANSFUSION Tony Chang, MD, Elizabeth Donegan, MD The infusion of blood and blood products from one individual to another to stop or prevent bleeding, provide adequate oxygen delivery, and to prevent death from hemorrhage saves millions of lives. Nevertheless, the practice of Transfusion Medicine remains in its infancy. In the 20th century, blood transfusion became a relatively safe and common practice, despite the relative absence of transfusion guidelines based on randomized, prospective controlled trials. Most transfusion practices are based on convention and convenience. The understanding of hemostasis, safe transfusion practices, appropriate testing of blood and blood products, as well as the consequences of transfusion continues to unfold. An understanding of these principles is very important for anesthetists who transfuse about half of the blood transfused in hospitals. Without this knowledge, transfusion practices often result in poor outcomes. This chapter will discuss the current understanding of hemostasis, laboratory tests that assist in the decision of which components or products to transfuse and when to transfuse. Current pediatric transfusion practices, and the laboratory collection, preparation, and testing of blood and blood components are included. HEMOSTASIS Hemostasis is now understood to be a complex system of checks and balances designed to prevent abnormal clotting and uncontrolled bleeding. Coagulation is a cell-based event initiated on the surface of endothelial cells, in the subendothelium, and on platelets (Figure 4-1). 87 Chapter 4: HEMOSTASIS AND BLOOD TRANSFUSION Figure 4-1: Coagulation Overview of coagulation: Coagulation is activated when endothelium is disrupted and blood contacts tissue factor (TF). TF activates factor VII in turn activators factor X, which in combination with factor V, forms the prothombinase complex. -

The Bleeding Time: Review of Basic Principle, Clinical Applications, and Laboratory Pitfalls

ReviewArticle The Bleeding Time: Review of Basic Principle, Clinical Applications, and Laboratory Pitfalls Chaicharoen Tantanate, M.D. Department of Clinical Pathology, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok 10700, Thailand. ABSTRACT The bleeding time is one of the oldest tests for primary hemostasis which is still performed nowadays.This test evaluates mainly the primary hemostatic function. Some preanalytical variables including patients’ physiology and hema- tological status may impact test results. Various protocols of bleeding time are performed. Each method has pros and cons, although the template bleeding time is currently preferred over other methods because it is well-standardized. Interpretation of the results according to a well-established reference range is important. At the moment, indications of bleeding time are very limited due to its poor sensitivity and reproducibility. More sensitive and specific assays have been developed for the diagnosis of specific conditions. However bleeding time is still useful in uremic patients. A cautionary note - this test should not be used as a screening test for prediction of bleeding preoperatively. Keywords: Bleeding time, Clinical applications, Pitfalls Siriraj Med J 2013;65:24-29 E-journal: http://www.sirirajmedj.com INTRODUCTION platelets.8 In this outstanding article, Duke proposed a simple technique to explain hemorrhagic phenomena he bleeding time (BT) is one of the oldest tests for which he called the “bleeding time”. He demonstrated primary hemostasis which is still performed that the degree of prolongation of BT was related to the nowadays.1 This test evaluates the interaction severity of bleeding symptom and platelet count. More- Tbetween platelets and the small blood vessel wall at the over, the BT could be shortened when patients received skin. -

Mixing Study, Incubated APTT

Cleveland Clinic Laboratories Technical Brief Mixing Study, Incubated APTT Background Information Correction of the APTT in the mixing study suggests a coagu- The activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) is one of the lation factor deficiency in either the intrinsic pathway (factors most commonly used screening tests to investigate bleeding VIII, IX, XI and XII, high-molecular-weight kininogen [HMWK] patients, monitor anticoagulant therapy and as a screening or prekallikrein [PK]), or in the common pathway (also pro- test prior to surgery. The APTT measures the integrity of the longed PT) such as factor II, V and X. Deficiency of factors intrinsic and common pathways of the coagulation cascade. VIII, IX, and XI will present with bleeding, however, deficiency The prothrombin time (PT), another common screening test, of factor XII, or prekallikrein will not increase bleeding risk, measures the integrity of the extrinsic and common coagulation but may increase thrombotic risk. Further testing, such as pathway. The APTT is measured as the number of seconds clotting factor assays, is necessary to diagnose a specific for the patient’s plasma to form a fibrin clot after the addition factor deficiency. See Figure 1 for the diagnostic algorithm of an intrinsic pathway activator, phospholipid and calcium. used in the laboratory. A prolonged APTT can be caused by a coagulation factor There are three different types of inhibitors: deficiency or the presence of an inhibitor. The mixing study, 1. Inhibitors directly against specific factors such as factor incubated APTT, is used to investigate the cause of a prolonged VIII or factor V inhibitors, APTT result. -

PT and Aptt First-Line Coagulation Assays

PT and aPTT First-line coagulation assays > Pre-operative screening for a bleeding risk > Monitoring of medical treatment with anticoagulants > Initial assessment of thrombotic- or bleeding -abnormalities KeyKey FactsFacts Hemostasis activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT) Evaluation of the intrinsic pathway The activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is a global coagulation assay. A prolongation of the aPTT clotting time indicates an abnormality of the intrinsic and final common coagulation pathway. aPTT results are reported in seconds. Until now, there is no global standardization. The results are specific to the aPTT reagent of a manufacturer. > Monitoring of therapy with unfractionated heparin (UFH) > Hemophilia A, B and C Clinical relevance > Coagulation factor inhibitors > Phospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulants) activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT) Monitoring of anticoagulant therapy with UFH Unfractionated heparin is commonly used for anticoagulant prophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism (VTE), acute coronary syndromes or atrial fibrillation. It is either administered intravenously or subcutaneously. The short half-life of UFH provides flexibility in medical treatment. Monitoring the therapeutic dosage of unfractionated heparin is mandatory to prevent over- or under -anticoagulation levels in the blood plasma. The most common method for monitoring UFH is the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).1 Plasmatic Coagulation Cascade Coordinating the formation of a fibrin clot For coagulation, soluble fibrinogen of the blood plasma is converted into insoluble fibrin strands which form a mesh that traps thrombocytes and erythrocytes, producing a solid blood clot. This is coordinated by enzymatic coagulation factors present in the blood plasma. There are basically two pathways that both end in a final common pathway that leads to the formation of a fibrin clot. -

Clinical Research

BRITISH -MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 285 7 AUGUST 1982 397 Br Med J (Clin Res Ed): first published as 10.1136/bmj.285.6339.397 on 7 August 1982. Downloaded from CLINICAL RESEARCH Prediction of haemorrhagic diathesis in thrombocytopenia by mean platelet volume A ELDOR, M AVITZOUR, R OR, R HANNA, S PENCHAS Abstract Introduction The Coulter counter, model S Plus, provides a platelet Severe thrombocytopenia is usually associated with the develop- count and a mean platelet volume in all routine specimens ment of haemorrhagic diathesis, though not all patients with ofblood for cell count. The value of mean platelet volume severe thrombocytopenia develop a bleeding tendency.1 2 Platelet in the prediction of the haemostatic potential ofthrombo- number alone may therefore be an insufficient predictor of cytopenic patients was investigated in 175 patients with bleeding tendency in a particular patient. Several investigators haematological disorders who underwent 1473 blood have suggested that platelet size also affects the haemostatic counts over five months. Eighty-four haemorrhagic potential of some patients because the function of platelets episodes were detected, most in thrombocytopenic depends on their size under normal conditions and, particularly, patients. The mean platelet volume of patients with in thrombocytopenic states.' 15 Using in-vitro adhesion and haemorrhagic tendency was significantly lower (5-52 ± SD aggregation studies3-9 and in-vivo tests and observations such 017 fl) than that of patients without these tendencies as bleeding time