Rapid Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Authentic Specialized Martial Arts Training in India

Lamka Shaolin Disciple’s Union www.kungfudisciples.com Lamka Shaolin Disciples’ Union SPECIALIZED MARTIAL ARTS COURSE INFO http://www.kungfudisciples.com Introducing Authentic Specialized Martial Arts Training in India 1 Lamka Shaolin Disciple’s Union www.kungfudisciples.com BAGUA ZHANG: [12 Classes a Month] Introduction: Bagua Zhang 八卦掌 Bagua Zhang is a martial art that has existed in various forms for millennia, practiced secretly by Taoist hermits before it emerged from obscurity in the late 19th century C.E. The most famous modern proponent, Dong Hai Chuan, became the bodyguard of the Empress Dowager, and was a teacher well respected by China’s most famous masters. 1. It is characterized by fast circular footwork, agile body movements, and lightning-fast hands. It is one of the famous three Neijia (Internal) styles which also include Tai Chi Quan and Xingyi Quan. 2. It teaches the student to “Walk like a dragon, retrieve and spin like an ape, change momentum like an eagle, and be calm and steady like a waiting tiger.” The use of open palms instead of fists, and the use of “negative space” is one of the things that makes Bagua Zhang particularly good for defeating multiple opponents. 3. Bagua Zhang contains powerful strikes. But the emphasis on flow and constant change is what gives this art its versatility. The options to choose between strikes, throws, joint locks, pressure point control, and varying degrees of control, make this art useful for self-defense and for law enforcement. 4. Bagua Zhang training is very aerobic, and emphasizes stability and agility. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. August 27, 2018 to Sun. September 2, 2018 Monday August 27, 2018

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. August 27, 2018 to Sun. September 2, 2018 Monday August 27, 2018 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT REO Speedwagon Live The Big Interview REO Speedwagon is captured live on stage in New York during the 2017 “United We Rock” tour. Gene Simmons - He’s the most famous member of KISS, but Gene Simmons is also a tongue One of the biggest classic rock bands of all time, REO Speedwagon creates an unforgettable wagging, fire spitting, media & marketing mogul. performance featuring hit songs across their entire catalogue featuring “Take It On The Run,” “Keep On Loving You,” and “Don’t Let Him Go.” 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT The Big Interview 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT Styx - Dan Rather joins three of Styx’s legendary members for a Las Vegas performance and a Sing for the Day! Tommy Shaw and Contemporary Youth Orchestra candid interview about the past, present and future of one of rock’s most enduring bands. In celebration of the 10-year anniversary of Styx and CYO, Tommy Shaw is joined on stage by the Contemporary Youth Orchestra for a night featuring his catalogue of music, from his solo songs 10:00 AM ET / 7:00 AM PT to many of the band’s greatest hits. Chicago Chicago performs “Color My World”, “Feeling Stronger Everyday” and “25 or 6 to 4” in this special 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT performance. Rock Legends Billy Joel - Classic videos and leading music critics tell the story of Billy Joel, one of the world’s 11:00 AM ET / 8:00 AM PT most popular recording artists. -

General Information

GENERAL INFORMATION II MEDITERRANEAN WUSHU CHAMPIONSHIPS II MEDITERRANEAN KUNG FU CHAMPIONSHIPS MARSEILLE, FRANCE MAY 31 – JUNE 3, 2019 General Information of the II Mediterranean Wushu Championships THE II MEDITERRANEAN WUSHU CHAMPIONSHIPS THE II MEDITERRANEAN KUNG FU CHAMPIONSHIPS COMPETITION GENERAL INFORMATION DATE & PLACE The 2nd Mediterranean Wushu Championships & the 2nd Mediterranean Kung Fu Championships will take place between May 30 and June 3, 2019 in Marseille, France. VENUES Competition Venue : Palais des sports de Marseille (81, rue Raymond-Teissere, 13000 Marseille) COMPETITION EVENTS 1. Taolu Events (Optional Routines without Degree of Difficulty): a. Individual Events (10 events divided into male and female categories): Changquan, Nanquan, Daoshu, Jianshu, Nandao, Gunshu, Qiangshu, Nangun, Taijiquan, Taijijian. b. Duilian Events (1 event divided into male and female categories): 2-3 people in duilian without weapons, duilian with weapons, or duilian with barehands against weapons. 2. Sanda Events: a. Men’s divisions (11 events): 48 Kg, 52 Kg, 56 Kg, 60 Kg, 65 Kg, 70 Kg, 75 Kg, 80 Kg, 85 Kg, 90 Kg, +90 Kg. b. Women’s divisions (7 events): 48 Kg, 52 Kg, 56 Kg, 60 Kg, 65 Kg, 70 Kg, 75 Kg. 3. Traditional Kung Fu Events: a. Individual Barehand Routine Events (15 events divided into male and female categories): (i). Taijiquan Type Events: 1) Chen Style (Performance Content derived from: Traditional Routines, Compulsory 56 Posture Routine, IWUF New Compulsory Chen Style Taijiquan Routine); 2) Yang Style (Performance Content derived from: Traditional Routines, Compulsory 40 Posture Routine, IWUF New Compulsory Yang Style Taijiquan Routine); 3) Other Styles (Performance Content derived from: Traditional Wu Style Routines, Compulsory Wu style Routines, Traditional Wu (Hao) Style Routines, Compulsory Wu (Hao) 46 Posture Routine, Traditional Sun Style Routines, Compulsory Sun Style 73 Posture Routine, 42 Posture Standardized Taijiquan). -

Episode 327 – Paradigm Shifts | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 327 – Paradigm Shifts | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey everyone thanks for coming by this is whistlekickmartialartsradio and you're listening to episode 327. Today we're going to talk about Jeet Kune Do. My name's Jeremy Lesniak, I'm your host for the show on the founder at whistlekickmartialarts and I love traditional martial arts. I'm doing it all my life and now it's my job, it's my job to help you love the martial arts even more and I'll do whatever I can to make that happen. If you wanna check out our products our projects our services all the stuff we've got going on you could find that at whistlekick.com and you can find the show notes for this and all of our other episodes at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com most of them have a transcript. We're actually going back and transcribing all of the old episodes. So if you're in a spot where you can't listen but you could read you might want to check those out or of course for our friends who are hearing impaired we wanna make sure that we give as much as we can to all martial artists regardless of how they take in their entertainment. Let's talk about Jeet Kune Do. We've spent a lot of time talking about Bruce Lee on the show especially lately episode 305 with Mr. Matthew Polly talking about his book Bruce Lee a life received at ton of attention and we thought it might be good idea to dig deeper into part of the legacy that Bruce Lee left namely the martial arts style that isn't the style in a sense Jeet Kune Do. -

The Seven Forms of Lightsaber Combat Hyper-Reality and the Invention of the Martial Arts Benjamin N

CONTRIBUTOR Benjamin N. Judkins is co-editor of the journal Martial Arts Studies. With Jon Nielson he is co-author of The Creation of Wing Chun: A Social History of the Southern Chinese Martial Arts (SUNY, 2015). He is also author of the long-running martial arts studies blog, Kung Fu Tea: Martial Arts History, Wing Chun and Chinese Martial Studies (www.chinesemartialstudies.com). THE SEVEN FORMS OF LIGHTSABER COMBAT HYPER-REALITY AND THE INVENTION OF THE MARTIAL ARTS BENJAMIN N. JUDKINS DOI ABSTRACT 10.18573/j.2016.10067 Martial arts studies has entered a period of rapid conceptual development. Yet relatively few works have attempted to define the ‘martial arts’, our signature concept. This article evaluates a number of approaches to the problem by asking whether ‘lightsaber combat’ is a martial art. Inspired by a successful film KEYWORDs franchise, these increasingly popular practices combine elements of historical swordsmanship, modern combat sports, stage Star Wars, Lightsaber, Jedi, Hyper-Real choreography and a fictional worldview to ‘recreate’ the fighting Martial Arts, Invented Tradition, Definition methods of Jedi and Sith warriors. The rise of such hyper- of ‘Martial Arts’, Hyper-reality, Umberto real fighting systems may force us to reconsider a number of Eco, Sixt Wetzler. questions. What is the link between ‘authentic’ martial arts and history? Can an activity be a martial art even if its students and CITATION teachers do not claim it as such? Is our current body of theory capable of exploring the rise of hyper-real practices? Most Judkins, Benjamin N. importantly, what sort of theoretical work do we expect from 2016. -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

Eskrima: Filipino Martial Art Free

FREE ESKRIMA: FILIPINO MARTIAL ART PDF Krishna Godhania | 160 pages | 09 Jul 2010 | The Crowood Press Ltd | 9781847971524 | English | Ramsbury, United Kingdom Eskrima / Arnis / Kali | Which Martial Arts Thus, there are great benefits of Filipino martial arts. And at the end of this post, we offer a special training to develop your hand speed for self- defence. Eskrima: Filipino Martial Art Here to Start Training. Eskrima is one of the best ways to Eskrima: Filipino Martial Art or burn calories without your realizing it. It has a conducive exercise program that develops and enhances various fitness components, primarily the aerobic which improves your cardio. Eskrimadors are aware of the demand on cardio when performing Sinawali and Redonda nonstop for several minutes. In order to relate calorie burning to weight loss, the simple equation is this — 3, calories is equal to a pound of fat. Therefore, burning Eskrima: Filipino Martial Art amount of calories indicates removing one pound of body fat. A regular Arnis martial arts class can last about two hours, and its intensity may differ according to the power required in every session. There is indeed no doubt that Arnis Escrima is an excellent exercise, and the only determining factor in succeeding is whether the student can stand by the training until he or she begins losing weight. Double stick drills, is an aerobically challenging training because of the weight of the two kali sticks and the degree of coordination required to execute the intricate movements. It promotes muscle tonality of the arms, legs, and body parts involved in the exercise. -

Sword Fighting : a Manual for Actors & Directors Pdf, Epub, Ebook

SWORD FIGHTING : A MANUAL FOR ACTORS & DIRECTORS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Keith Ducklin | 192 pages | 01 May 2001 | Applause Theatre Book Publishers | 9781557834591 | English | New York, United States Sword Fighting : A Manual for Actors & Directors PDF Book Sportsmanship, Hook. Fencing techniques, The Princess Bride. Today, I'll be breaking down clips from movies and T. List of styles History Timeline Hard and soft. Cheng Man-Ch'ing Mercenary Sword. By Yang, Jwing-Ming. Afterword by John Stevens. Very dead. Half-speed doesn't mean half-fighting. Come and Fence with us! By Dorothy A. Boken Japanese wooden sword , Budo Way of Warrior. Come on, then! The broadsword was notable for its large hilt which allowed it to be wielded with both hands due to its size and weight. It was originally a short sword forged by the Elves, but made for a perfect weapon for Hobbits. Explanation in Mandarin by Yang Zhengduo. A Swordsmith and His Legacy. But what he's doing is a lot of deflecting parries that are happening, so as an attack's coming in he's moving out of the way and deflecting the energy of it so that's how he's able to go up against steel. What the Studio Did: The Movie was near completion when Dean passed away, in fact all of scenes were completed. Experiences and practice. Garofalo's E-mail. Generally more common in modern contemporary plays, after swords have gone out of style but also seen in older plays such as Shakespeare's Othello when Othello strangles Desdemona. With the sudden end of constant war, the samurai class slowly became unmoored. -

Cubed Circle Newsletter 241 – Consistency Is Hard

Cubed Circle Newsletter 241 – Consistency is Hard As many of probably noticed, we have been posting late and sporadically for the last month. This was, obviously, not our intention, but with the second semester eating into my free time, staying up to date is a tall order. Even without the newsletter itself seeing weekly publication the site has still remained up to date on a weekly basis, thanks primarily to co-author Ben Carass, as well as guest writers Paul Cooke and Leslie Lee III. But, the newsletter has survived for well over 241 weeks, and will hopefully thrive in the years to come. I have attempted to make provisions for publishing related tasks which should minimize the risk of major delays (obviously there will be some regular delays, as this late issue can attest), but we have some fail safes in place in order to keep this to a minimum. With all of this said, we have a great issue for everyone this week with Paul Cooke discussing the Pro-Wrestling Only Greatest Wrestler Ever project and his personal experience with the poll, Ben covers the news including tons of results from Japan and the Lesnar USADA violation, the Mixed Bag returns with a look at comedy wrestling, Ricochet/Ospreay, and a potential WWE match of the year -- plus Ben also looks at last Sunday's Battleground show and the first RAW of the brand split (a very good show). Also, for those unaware, we now have an official Twitter account @CubedCircleWres allowing the banger to unprecedented highs at @BenCarass and @RyanClingman. -

Animating Race the Production and Ascription of Asian-Ness in the Animation of Avatar: the Last Airbender and the Legend of Korra

Animating Race The Production and Ascription of Asian-ness in the Animation of Avatar: The Last Airbender and The Legend of Korra Francis M. Agnoli Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Art, Media and American Studies April 2020 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution. 2 Abstract How and by what means is race ascribed to an animated body? My thesis addresses this question by reconstructing the production narratives around the Nickelodeon television series Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-08) and its sequel The Legend of Korra (2012-14). Through original and preexisting interviews, I determine how the ascription of race occurs at every stage of production. To do so, I triangulate theories related to race as a social construct, using a definition composed by sociologists Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer; re-presentations of the body in animation, drawing upon art historian Nicholas Mirzoeff’s concept of the bodyscape; and the cinematic voice as described by film scholars Rick Altman, Mary Ann Doane, Michel Chion, and Gianluca Sergi. Even production processes not directly related to character design, animation, or performance contribute to the ascription of race. Therefore, this thesis also references writings on culture, such as those on cultural appropriation, cultural flow/traffic, and transculturation; fantasy, an impulse to break away from mimesis; and realist animation conventions, which relates to Paul Wells’ concept of hyper-realism. -

The Primary Purpose of Womau and Suggestions on IMAC of Primarythe Purpose Womau

Summer 2019 News 세계무술연맹의 근본 목적과 국제무예연무대회에 대한 제언 The Primary Purpose of WoMAU and Suggestions on IMAC of PrimaryThe Purpose WoMAU ISSN 2234-1218 No.29 2019 Summer WoMAU News CONTENTS WoMAU News No. 29 Summer 2019 WoMAU News aims to be an archive containing valuable information on martial arts and the activities of the WoMAU in the field of martial arts as well as to be a source of both academic knowledge and practical information of Traditional Sports and Games with a special focus on martial arts. Plus, it also aims to raise awareness on martial arts by promoting the exchange of knowledge and information of martial arts across the globe. Remarks 대표 발언 Members’ News 회원 소식 04 The Primary purpose of WoMAU and 37 The 15th World Horseback Archery Suggestions on IMAC Championship will be held in Sokcho 세계무술연맹의 근본 목적과 국제무예연무대회에 제15회 세계기사선수권대회 개최 대한 제언 38 ‘Ssireum’ marked the joint listing of the two Koreas on UNESCO's ICH list Expert’s Column 전문가 칼럼 ‘한국의 씨름’ UNESCO 인류무형문화유산 08 Culture ODA & Sports Development Cooperation 남북 공동 등재 기념 행사 개최 문화 ODA와 스포츠 개발협력 39 Mr. Richardson Gialogo, a Vice-President of WoMAU to as an Arnis representative Icon 14 The Study of Martial Arts in the Fourth of National game Industrial Revolution 연맹 부의장(리처드슨 지알로고), 아르니스 대표로 4차 산업 시대의 무술 연구 국가 경기 대표 아이콘 활약 19 Martial Arts in Russia - Retrospect and Prospect 40 Remarkable Martial Arts Activities 러시아 무술 회고와 전망 by Association of Renaissance Martial Arts 르네상스무술협회(ARMA)의 2019 무술 활동 성과 Special Column 특별 칼럼 42 Released “OKICHITAW-Refeathering 26 Reflection on the advisory functions of accredited the Warrior” Canadian indigenous martial arts non-governmental organizations(NGO) documentary film 유네스코 비정부기구(NGO)의 역할 증대 움직임 캐나다 토속 무술 기록 영화, <오키치타우-전사에게 다시 날개를> 개봉 33 Recent trends in UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage(ICH) Inscriptions and evaluations 43 Uzbekistan JJang-Sanati Federation hosted 유네스코 무형유산 등재 현황과 심사 동향 Uzbekistan Championship 우즈벡장사나티연맹, 우즈베키스탄 선수권 대회 개최 WoMAU News is a magazine published twice a year by World Martial Arts Union. -

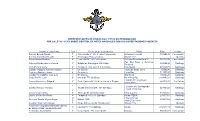

Representantes-22.OCT .14.Pdf

REPRESENTANTES DE DISCIPLINAS Y ESTILOS RECONOCIDOS POR LA LEY Nº 18.356 SOBRE CONTROL DE ARTES MARCIALES CON SUS ACREDITACIONES VIGENTES Nombres y Apellidos Dan Dirección de la academia Estilo Fono Ciudad Alarcón Belmar Oscar 7° Calle Heras N° 813 2° piso Concepción. Defensa Personal 74760436 Concepción Barrera Arancibia Ricardo 8° Aconcagua 752 La Calera. Shaolin Tse Quillota Bruna Urrutia Rodrigo 4° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. Defensa Personal Israelí 56373506 Concepción Pak Mei Kune y Defensa Cabrera Maldonado Hortensia 7° Batalla de Rancagua 539 Maipú. 88550636 Santiago Personal Caro Pizarro Víctor 5° Tarapacá 1324 local 3 A Santiago. Krav Maga 98528875 Santiago Catalán Vásquez Alberto Mauricio 4° En trámite. Taijiquan Estilo Chen 6890530 Santiago Cavieres Martínez Jorge 6° En trámite. Hung Gar 71377097 Santiago Candia Hormazabal José Luis 5° En trámite. Wai Kung 78696520 Santiago Colipí Curiñir Juan 6° Morandé 771 Santiago. Nam Hwa Pai 2-6880123 Santiago Hapkido Cheong Kyum Correa Manríquez Edgard 5° Calle Carrera N° 1624 La Calera V Región. 94171533 La Calera Association. 5° - Choson Mu Sul Hapkido Cubillos Alarcón Richard Vicuña Mackenna N° 227 Santiago. 22472122 Santiago - Pekiti Tirsia Kali 4° Collao Vega Carlos 6° Alameda N° 2489 Santiago Choy Lay Fut 73333201 Santiago Daiber Vuillemín Alberto 4° Tarapacá 777(779) Santiago. Aikikai-FEPAI 29131087 Santiago 9° - Tsung Chiao De Luca Garate Miguel Angel Bilbao 1559 98221052 Santiago 5° - Hung Gar Kuen Escobar Silva Luis Antonio 7° Diego Echeverría N° 786 Quillota. Shaolin Tao Quillota Federación Deportiva Nacional Chilena 6° Libertad N° 86 Santiago. Aikikai 2-6817703 Santiago de Aikido Aikikai (FEDENACHAA) Fernández Soria Mario 5° Castellón N° 292 Concepción.