The Art of Badger Bates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

3 Researchers and Coranderrk

3 Researchers and Coranderrk Coranderrk was an important focus of research for anthropologists, archaeologists, naturalists, historians and others with an interest in Australian Aboriginal people. Lydon (2005: 170) describes researchers treating Coranderrk as ‘a kind of ethno- logical archive’. Cawte (1986: 36) has argued that there was a strand of colonial thought – which may be characterised as imperialist, self-congratulatory, and social Darwinist – that regarded Australia as an ‘evolutionary museum in which the primi- tive and civilised races could be studied side by side – at least while the remnants of the former survived’. This chapter considers contributions from six researchers – E.H. Giglioli, H.N. Moseley, C.J.D. Charnay, Rev. J. Mathew, L.W.G. Büchner, and Professor F.R. von Luschan – and a 1921 comment from a primary school teacher, named J.M. Provan, who was concerned about the impact the proposed closure of Coranderrk would have on the ability to conduct research into Aboriginal people. Ethel Shaw (1949: 29–30) has discussed the interaction of Aboriginal residents and researchers, explaining the need for a nuanced understanding of the research setting: The Aborigine does not tell everything; he has learnt to keep silent on some aspects of his life. There is not a tribe in Australia which does not know about the whites and their ideas on certain subjects. News passes quickly from one tribe to another, and they are quick to mislead the inquirer if it suits their purpose. Mr. Howitt, Mr. Matthews, and others, who made a study of the Aborigines, often visited Coranderrk, and were given much assistance by Mr. -

Australian Settler Bush Huts and Indigenous Bark-Strippers: Origins and Influences

Australian settler bush huts and Indigenous bark-strippers: Origins and influences Ray Kerkhove and Cathy Keys [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This article considers the history of the Australian bush hut and its common building material: bark sheeting. It compares this with traditional Aboriginal bark sheeting and cladding, and considers the role of Aboriginal ‘bark strippers’ and Aboriginal builders in establishing salient features of the bush hut. The main focus is the Queensland region up to the 1870s. Introduction For over a century, studies of vernacular architectures in Australia prioritised European high-style colonial vernacular traditions.1 Critical analyses of early Australian colonial vernacular architecture, such as the bush or bark huts of early settlers, were scarce.2 It was assumed Indigenous influences on any European-Australian architecture could not have been consequential.3 This mirrored the global tendency of architectural research, focusing on Western tradi- tions and overlooking Indigenous contributions.4 Over the last two decades, greater appreciation for Australian Indigenous archi- tectures has arisen, especially through Paul Memmott’s ground-breaking Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley: The Indigenous Architecture of Australia (2007). This was recently enhanced by Our Voices: Indigeneity and Architecture (2018) and the Handbook of Indigenous Architecture (2018). The latter volumes located architec- tural expressions of Indigenous identity within broader international movements.5 Despite growing interest in the crossover of Australian Indigenous architectural expertise into early colonial vernacular architectures,6 consideration of intercultural architectural exchange remains limited.7 This article focuses on the early settler Australian bush hut – specifically its widespread use of bark sheets as cladding. -

Australian Indigenous Virtual Heritage

1 Australian Aboriginal Virtual Heritage A philosophical and technical foundation for using new media hardware and software technologies to preserve, protect and present Aboriginal cultural heritage and knowledge. Protecting, preserving and promoting Aboriginal arts, cultures, heritage and knowledge using 3D virtual technologies. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research), Creative Industries Faculty, Queensland University of Technology, 2014 Image 1 - This virtual screen shot is from Vincent’s World and represents a re-create of a view and path (Songline) around the base of the Tombs in the Mt Moffatt Section of Carnarvon Gorge. This document meets the requirements of a presentation of thesis by published as specified in Section 123 of the Queensland University of Technology MOPP. 2 Keywords Australia, Aboriginal Australia, Aboriginal Virtual Heritage, Aboriginal Digital Heritage, Indigenous history, arts and culture, virtual technologies, virtual reality, digital knowledge management, virtual culture, digital culture, digital mapping, spatial knowledge management, spatial systems 3 Abstract Cultural knowledge is a central tenant of identity for Aboriginal people and it is vitally important that the preservation of heritage values happens. Digital Songlines is a project that seeks to achieve this and was initiated as a way to develop the tools for recording cultural heritage knowledge in a 3D virtual environment. Following the delivery of a number of pilots the plan is to develop the software as a tool and creative process that anyone can use to record tangible and intangible natural and cultural heritage knowledge and to record the special significance of this knowledge as determined by the traditional owners. -

Nyungar Tradition

Nyungar Tradition : glimpses of Aborigines of south-western Australia 1829-1914 by Lois Tilbrook Background notice about the digital version of this publication: Nyungar Tradition was published in 1983 and is no longer in print. In response to many requests, the AIATSIS Library has received permission to digitise and make it available on our website. This book is an invaluable source for the family and social history of the Nyungar people of south western Australia. In recognition of the book's importance, the Library has indexed this book comprehensively in its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI). Nyungar Tradition by Lois Tilbrook is based on the South West Aboriginal Studies project (SWAS) - in which photographs have been assembled, not only from mission and government sources but also, importantly in Part ll, from the families. Though some of these are studio shots, many are amateur snapshots. The main purpose of the project was to link the photographs to the genealogical trees of several families in the area, including but not limited to Hansen, Adams, Garlett, Bennell and McGuire, enhancing their value as visual documents. The AIATSIS Library acknowledges there are varying opinions on the information in this book. An alternative higher resolution electronic version of this book (PDF, 45.5Mb) is available from the following link. Please note the very large file size. http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/e_access/book/m0022954/m0022954_a.pdf Consult the following resources for more information: Search the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI) : ABI contains an extensive index of persons mentioned in Nyungar tradition. -

![Page 10, Born a Half Caste by Marnie Kennedy K365.60B2 AIATSIS Collection]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4813/page-10-born-a-half-caste-by-marnie-kennedy-k365-60b2-aiatsis-collection-934813.webp)

Page 10, Born a Half Caste by Marnie Kennedy K365.60B2 AIATSIS Collection]

*************************************************************** * * * WARNING: Please be aware that some caption lists contain * * language, words or descriptions which may be considered * * offensive or distressing. * * These words reflect the attitude of the photographer * * and/or the period in which the photograph was taken. * * * * Please also be aware that caption lists may contain * * references to deceased people which may cause sadness or * * distress. * * * *************************************************************** Scroll down to view captions MASSOLA.A01.CS (000079378-000080404; 000080604-000080753) The Aldo Massola collection: historical and contemporary images from mainland Australia. South Australia; Northern Territory; Queensland; Western Australia; Victoria; New South Wales ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: MASSOLA.A01.CS-000079378 Date/Place taken: [1950-1963] : Yalata, S.A. Title: [Unidentified men, women and children possibly participating with Catherine Ellis regarding a] tape recording Photographer/Artist: Access: Conditions apply Notes: Catherine Ellis 1935-1996 - Pioneer of research in the field of Australian Aboriginal music ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: MASSOLA.A01.CS-000079379 Date/Place taken: [1950-1963] : Yalata, S.A. Title: [Portrait of a unidentified] woman with child [sitting on her back in a sling] Photographer/Artist: Access: Conditions apply Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: MASSOLA.A01.CS-000079380 Date/Place taken: [1950-1963] : Yalata, S.A. Title: Boys with balloons [playing -

The Muruwari Language

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series C - No.108 THE MURUW ARI LANGUAGE Lynette F. Oates Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Oates, L.F. The Muruwari Language. C-108, xxiv + 439 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1988. DOI:10.15144/PL-C108.cover ©1988 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: T.E. Dutton, D.C. Laycock, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B.W.Bender H.P. McKaughan University of Hawaii University of Hawaii David Bradley P. Miihlhausler LaTrobe University Bond University Michael G. Clyne G.N. O'Grady Monash University University of Victoria, B.C. S.H. Elbert A.K. Pawley University of Hawaii University of Auckland KJ. Franklin K.L. Pike Summer Institute of Linguistics Summer Institute of Linguistics W.W. Glover E.C. Polome Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Texas G.W.Grace Gillian Sankoff University of Hawaii University of Pennsylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A.L. Stokhof University of Sydney University of Leiden E. Haugen B.K. T'sou HarvardUniversity City Polytechnic of Hong Kong A. Healey E.M. Uhlenbeck Summer Institute of Linguistics University of Leiden L.A. Hercus J.W.M. Verhaar Australian National University Divine Word Institute, Madang John Lynch C.L. -

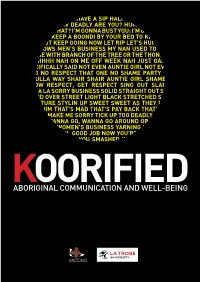

Koorified | Aboriginal Communication and Well-Being CONTENTS

GUNNA HAVE A DORIE HAVE A SIP HALF CHARGED HAMMERED HOLD UP NOW HOW DEADLY ARE YOU? HUMBUG I DIDN’T JERI IGNORANT OR WHAT? I’M GONNA BUST YOU: I’M GUNNA FLOG YOU IF YOU DON’T KEEP A BOONDI BY YOUR BED TO KEEP ‘EM IN OR KEEP ‘EM OUT KEEP GOING NOW LET RIP LET’S HUMP IT LISTEN UP, NOW LOWS MEN’S BUSINESS MY NAN USED TO THREATEN TO FLOG ME WITH BRANCH OF THE TREE OR THE THONG OFF HER FOOT NAHHHH NAH ON ME OFF WEEK NAH JUST GAMMON AY NO! I PACIFICALLY SAID NOT EVEN AUNTIE GIRL NOT EVEN BUDJ NOTHING NO RESPECT THAT ONE NO SHAME PARTY UP REAL BLACKFULLA WAY SHAIR SHAIR AUNTIE GIRL SHAME SHAME JOB SHOW RESPECT, GET RESPECT SING OUT SLAPPED UP SOOKIE LA LA SORRY BUSINESS SOLID STRAIGHT OUT STRAIGHT UP? STAND OVER STREET LIGHT BLACK STRETCHED STRONG IN YOUR CULTURE STYLIN UP SWEET SWEET AS THEY DON’T GET IT THAT’S HIM THAT’S MAD THAT’S PAY BACK THAT’S SIC THEY GET IT THEY MAKE ME SORRY TICK UP TOO DEADLY TRUE? TRUE THAT UNNA WANNA GO, WANNA GO AROUND OR WANNA HAVE A CRACK WHA? WOMEN’S BUSINESS YARNING YARNING UP BIG TIME YEAH AY YEAH, GOOD JOB NOW YOU’RE DEADLY YOU’RE A KILLER YOU KILLED IT YOU SMASHED IT YOU’RE A DORIS YOU MAKE ME WEAK KOORIFIED ABORIGINAL COMMUNICATION AND WELL-BEING KOORIFIED ABORIGINAL COMMUNICATION AND WELL-BEING This document was developed through a partnership between the The School of Nursing and Midwifery at LaTrobe University and the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (VACCHO). -

Provenance 2008

Provenance 2008 Issue 7, 2008 ISSN: 1832-2522 Index About Provenance 2 Editorial 4 Refereed articles 6 Lyn Payne The Curious Case of the Wollaston Affair 7 Victoria Haskins ‘Give to us the People we would Love to be amongst us’: The Aboriginal Campaign against Caroline Bulmer’s Eviction from Lake Tyers Aboriginal Station, 1913-14 19 Robyn Ballinger Landscapes of Abundance and Scarcity on the Northern Plains of Victoria 28 Belinda Robson From Mental Hygiene to Community Mental Health: Psychiatrists and Victorian Public Administration from the 1940s to 1990s 36 Annamaria Davine Italian Speakers on the Walhalla Goldfield: A Micro-History Approach 48 Forum articles 58 Karin Derkley ‘The present depression has brought me down to zero’: Northcote High School during the 1930s 59 Ruth Dwyer A Jewellery Manufactory in Melbourne: Rosenthal, Aronson & Company 65 Dawn Peel Colac 1857: Snapshot of a Colonial Settlement 73 Jenny Carter Wanted! Honourable Gentlemen: Select Applicants for the Position of Deputy Registrar for Collingwood in 1864 82 Peter Davies ‘A lonely, narrow valley’: Teaching at an Otways Outpost 89 Brienne Callahan The ‘Monster Petition’ and the Women of Davis Street 96 1 About Provenance The journal of Public Record Office Victoria Provenance is a free journal published online by Editorial Board Public Record Office Victoria. The journal features peer- reviewed articles, as well as other written contributions, The editorial board includes representatives of: that contain research drawing on records in the state • Public Record Office Victoria access services; archives holdings. • the peak bodies of PROV’s major user and stakeholder Provenance is available online at www.prov.vic.gov.au groups; The purpose of Provenance is to foster access to PROV’s • and the archives, records and information archival holdings and broaden its relevance to the wider management professions. -

Cultural Resources Culturally Inspired Music

187 CULTURAL RESOURCES 193 197 200 201 The beauty of the world lies in the diversity of its people CULTURAL RESOURCES CULTURALLY INSPIRED MUSIC ......................... 190 206 INDIGENOUS LEARNING .............................. 196 INDIGENOUS & MULTICULTURAL PUZZLES....... 210 INDIGENOUS STYLED MATS & CUSHIONS ..... 194 MULTICULTURAL BOOKS ................................ 204 MULTICULTURAL CRAFT RESOURCES ............... 188 MULTICULTURAL DRAMATIC PLAY .................... 206 195 FREE FREIGHT* 187 PHONE 1300 365 268 SHOP ONLINE www.bellbird.com.au ON ORDERS OVER $200 Bellbird ERC2019 - Cultural Resources FINAL.indd 187 24/01/2019 8:18:33 PM 188 Multicultural Craft Resources CULTURAL RESOURCES Poster Colours Paint Blocks Thick Set Lyra Colour Giant Pencils Large Oil Pastels 111922 Earth (includes Palette) 6pk ......... $10.95 112693 Skin Tones 12pk......................... $15.95 112655 Assorted Skin Tones 12pk ............. $5.95 111924 Refill Earth 6pk ............................ $7.50 A chunky colouring pencil with hexagonal shape and A set of 12 non-toxic, highly pigmented oil pastels that Long lasting poster colour paint is both easy to use and 10mm diameter. Extra strong colour thanks to highly have vivid colours and glide on smoothly with excellent to store, making it an ideal option for classrooms. Just pigmented, extra thick break-resistant lead (6.25mm). coverage. Each pastel is wrapped to keep little hands add water! These paints are easy to clean up and will The colours are smudge proof and waterproof. Set clean and their large size helps apply colour faster. not result in any wastage. Colours are intermixable and includes varying skin tones. Age: 3+ yrs Age: 3+ yrs refillable. Size: 44 x 16mm Multicultural Craft Resources EC Liquicryl People Paint 500ml 112021A Peach ........................................ -

The Ethics of Indigenous Storytelling

The Ethics of Indigenous Storytelling: using the Torque Game Engine to Support Australian Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Theodor G Wyeld Brett Leavy The University of Adelaide, ACID Cyberdreaming, ACID Adelaide, Australia. Brisbane, Australia [email protected] [email protected] Joti Carroll Craig Gibbons ACID ACID Brisbane, Australia Brisbane, Australia [email protected] [email protected] Brendan Ledwich James Hills ACID SGI, ACID Brisbane, Australia Brisbane, Australia [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Digital Songlines (DSL) is an Australasian CRC for Author Keywords Cultural Heritage, Storytelling, Torque Game Engine, Interaction Design (ACID) project that is developing Indigenous Heritage. protocols, methodologies and toolkits to facilitate the collection, education and sharing of indigenous cultural INTRODUCTION heritage knowledge. This paper outlines the goals achieved Digital Songlines (DSL) is an Australasian CRC for over the last three years in the ethics of developing the Interaction Design (ACID) project that is developing Digital Songlines game engine (DSE) toolkit that is used protocols, methodologies and toolkits to facilitate the for Australian Indigenous storytelling. The project explores collection, education and sharing of indigenous cultural the sharing of indigenous Australian Aboriginal storytelling heritage knowledge. This paper outlines the goals achieved in a sensitive manner using a game engine. over the last three years in the ethics of developing the The use of game engine -

Jackomos.A13.Bw .Pdf (Pdf, 144.43

************************************************************** * * * WARNING: Please be aware that some caption lists contain * * language, words or descriptions which may be considered * * offensive or distressing. * * These words reflect the attitude of the photographer * * and/or the period in which the photograph was taken. * * * * Please also be aware that caption lists may contain * * references to deceased people which may cause sadness or * * distress. * ************************************************************** Scroll down to view captions JACKOMOS.A13.BW (N05342-N05344) Portraits of Aboriginal servicemen and women, and other prominent Aboriginal figures Vic.; N.S.W.; Qld.; W.A.; Papua New Guinea, 1870-1991 Item no.: JACKOMOS.A13.BW-N05342_02 Date/Place taken: c1870 : Coranderrk, Vic. Title: [Unidentified] Aboriginal stockman Photographer/Artist: Access: Open access Notes: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: JACKOMOS.A13.BW-N05342_03 Date/Place taken: Late 1880s : Coranderrk, Vic. Title: [Wooden shelter with family sitting outside] Photographer/Artist: Access: Open access Notes: Copyright Museum of Victoria BPA 101, Coranderrk 9 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: JACKOMOS.A13.BW-N05342_04 Date/Place taken: Late 1880s : Coranderrk, Vic. Title: View of station Photographer/Artist: Access: Open access Notes: Copyright Museum of Victoria BPA 101, Coranderrk 9 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: JACKOMOS.A13.BW-N05342_05 Date/Place taken: 1910-1911 : Coranderrk, Vic. Title: Alec McRae holding Dorothy, Mary McRae holding Angeline (born 12 December 1909) Photographer/Artist: Access: Open access Notes: Dorothy married Don Turner, Angeline married Charlie Morgan ++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Item no.: JACKOMOS.A13.BW-N05342_06 Date/Place taken: Late 1930s : Cummeragunja, N.S.W. Title: [Group portrait of] the Merri Singers and Dancers Photographer/Artist: Access: Open access Notes: Back row (left to right): Alec Cooper; Vivien Cooper; Jack Cooper; Wally Nicholls (brother of Doug Nicholls).