Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Tower Inspiration Page 6

The newspaper for BBC pensioners – with highlights from Ariel online East Tower inspiration Page 6 AUGUST 2014 • Issue 4 TV news celebrates Remembering Great (BBC) 60 years Bing Scots Page 2 Page 7 Page 8 NEWS • MEMORIES • CLASSIFIEDS • YOUR LETTERS • OBITUARIES • CROSPERO 02 BACK AT THE BBC TV news celebrates its 60th birthday Sixty years ago, the first ever BBC TV news bulletin was aired – wedged in between a cricket match and a Royal visit to an agriculture show. Not much has changed, has it? people’s childhoods, of people’s lives,’ lead to 24-hour news channels. she adds. But back in 1983, when round the clock How much!?! But BBC TV news did not evolve in news was still a distant dream, there were a vacuum. bigger priorities than the 2-3am slot in the One of the original Humpty toys made ‘A large part of the story was intense nation’s daily news intake. for the BBC children’s TV programme competition and innovation between the On 17 January at 6.30am, Breakfast Time Play School has sold at auction in Oxford BBC and ITV, and then with Channel 4 over became the country’s first early-morning TV for £6,250. many years,’ says Taylor. news programme. Bonhams had valued the 53cm-high The competition was evident almost ‘It was another move towards the sense toy at £1,200. immediately. The BBC, wary of its new that news is happening all the time,’ says The auction house called Humpty rival’s cutting-edge format, exhibited its Hockaday. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

Shakespeare and London Programme

andShakespeare London A FREE EXHIBITION at London Metropolitan Archives from 28 May to 26 September 2013, including, at advertised times, THE SHAKESPEARE DEED A property deed signed by Mr. William Shakespeare, one of only six known examples of his signature. Also featuring documents from his lifetime along with maps, photographs, prints and models which explore his relationship with the great metropolis of LONDONHighlights will include the great panoramas of London by Hollar and Visscher, a wall of portraits of Mr Shakespeare, Mr. David Garrick’s signature, 16th century maps of the metropolis, 19th century playbills, a 1951 wooden model of The Globe Theatre and ephemera, performance recording and a gown from Shakespeare’s Globe. andShakespeare London In 1613 William Shakespeare purchased a property in Blackfriars, close to the Blackfriars Theatre and just across the river from the Globe Theatre. These were the venues used by The Kings Men (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men) the performance group to which he belonged throughout most of his career. The counterpart deed he signed during the sale is one of the treasures we care for in the City of London’s collections and is on public display for the first time at London Metropolitan Archives. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the document, this exhibition explores Shakespeare’s relationship with London through images, documents and maps drawn from the archives. From records created during his lifetime to contemporary performances of his plays, these documents follow the development of his work by dramatists and the ways in which the ‘bardologists’ have kept William Shakespeare alive in the fabric of the city through the centuries. -

UK-Films-For-Sale-TIFF-2017.Pdf

10X10 TAltitude Film Sales Cast: Luke Evans, Kelly Reilly Vicki Brown Genre: Thriller [email protected] Director: Suzi Ewing Market Office: UK Film Centre Status: Post-Production Home Office tel: +44 20 7478 7612 Synopsis: After meticulous planning and preparation, Lewis snatches Cathy off the busy streets and locks her away in a soundproofed room measuring 10 feet by 10 feet. His motive - to have Cathy confess to a dark secret that she is determined to keep hidden. But, Cathy has no intention of giving up so easily. All The Devil's Men TGFM Films Cast: Milo Gibson, Gbenga Akinnagbe, Sylvia Hoeks, Morgan Spector, Edoardo Bussi +44 7511 816295 William Fichtner [email protected] Genre: Action/Adventure Market Office: UK Film Centre Director: Matthew Hope Home Office tel: +44 20 7186 6300 Status: Post-Production Synopsis: A battle-scarred War on Terror bounty hunter is forced to go to London on a manhunt for a disavowed CIA operative, which leads him into a deadly running battle with a former military comrade and his private army. Apostasy Discovery TCornerstone Films Genre: Drama David Charles +44 7827 948 674 Director: Daniel Kokotajlo [email protected] Status: Completed Market Office: UK Film Centre Home Office tel: +44 20 3457 7257 Synopsis: Family and faith come into conflict for two Jehovah’s Witness sisters in Manchester, when one is condemned for fornication and the other pressured to shun her sibling. This fresh, unadorned first feature from director Dan Kokotajlo carries an unmistakable note of authenticity from its very first scenes. Set in a Jehovah's Witness community in England, the film's strength and power lies in its directness. -

Spring 2008-Final

Wagneriana Endloser Grimm! Ewiger Gram! Spring 2008 Der Traurigste bin ich von Allen! Volume 5, Number 2 —Die Walküre From the Editor ven though the much-awaited concert of the Wagner/Liszt piano transcriptions was canceled due to un- avoidable circumstances (the musicians were unable to obtain a visa), the winter and early spring months E brought several stimulating events. On January 19, Vice President Erika Reitshamer gave an audiovisual presentation on Wagner’s early opera Das Liebesverbot. This well-attended event was augmented by photocopies of extended excerpts from the libretto, with frequently amusing commentary by the presenter on Wagner’s influences and foreshadowings of his future operas. February 23 brought the excellent talk by Professor Hans Rudolf Vaget of Smith College. Professor Vaget spoke about Wagner’s English biographer Ernest Newman, whose seminal four-volume book The Life of Richard Wagner has never been surpassed in its thoroughness. In the early part of the twentieth century, the music critic Newman served as a counterbalance to his fellow countryman Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Wagner’s son-in-law and an ardent Nazi. The talk also included aspects of Thomas Mann’s fictional writings on Wagner, as well as the philoso- pher and musician Theodor Adorno and Wagner’s other son-in-law Franz Beidler. On April 19 we learned the extent of Buddhism’s influence on Wagner’s operas thanks to a lecture and book signing by Paul Schofield, author of The Redeemer Reborn: Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring. The audience members were so interested in what Mr. -

Jahresbericht 2009 Richard Wagner Verband Regensburg E.V

Richard Wagner Verband Regensburg e.V. ************************************************************************* Emil Kerzdörfer, 1. Vorsitzender Kaiser - Friedrich - Allee 46 D - 93051 Regensburg Tel: (0049)-941-95582 Fax: (0049)-941-92655 [email protected] www.Richard-Wagner-Verband-Regensburg.de ************************************************************************* Jahresbericht 2009 ********************************* Motto: „Ich kann den Geist der Musik nicht anders fassen als in Liebe“ Richard Wagner (1813 - 1883) 1. Vorsitzender: Emil Kerzdörfer 09. bis 10. Januar: Kulturreise nach Dresden Führung durch das neue Grüne Gewölbe Führung Sonderausstellung "Goldener Drache - Weißer Adler" im Residenzschloss Dresden Semper-Oper Franz Lehar „ Die lustige Witwe“ Kulturrathaus Dresden – Festsaal: Vortrag Klaus Weinhold: „Richard Wagner, Dresdner Lebensabschnitte. Eine Spurensuche“. Richard Wagner: „Siegfried-Idyll“ – WWV 103 Mitglieder der Staatskapelle Dresden Kulturrathaus Dresden – Festsaal: Vortrag Franziska Jahn : „Siegfried Wagner – Sein Schaffen in der Musikwelt“ 11. Januar: Konzertfahrt in die Philharmonie nach München, Thielemann-Zyklus Gabriel Fauré: Orchestersuite „Pelleas et Melisande“, op. 80 Ernest Chausson: „Poème“ für Violine und Orchester, Es-Dur, op. 25 Georges Bizet/ „Carmen-Fantasie“ für Violine und Orchester Max Waxman: Claude Debussy: „Images“ Solist : Vadim Repin, Violine Dirigent : Christian Thielemann - 2 - 14. Januar : Wort & Ton“ im Kolpinghaus Einführungsvortrag: Emil Kerzdörfer: „Der Rosenkavalier“ -

Lavinia Roberts Big Dog Publishing

Lavinia Roberts Big Dog Publishing Shakespeare’s Next Top Fool 2 Copyright © 2018, Lavinia Roberts ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Shakespeare’s Next Top Fool is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and all of the countries covered by the Universal Copyright Convention and countries with which the United States has bilateral copyright relations including Canada, Mexico, Australia, and all nations of the United Kingdom. Copying or reproducing all or any part of this book in any manner is strictly forbidden by law. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or videotaping without written permission from the publisher. A royalty is due for every performance of this play whether admission is charged or not. A “performance” is any presentation in which an audience of any size is admitted. The name of the author must appear on all programs, printing, and advertising for the play and must also contain the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Big Dog/Norman Maine Publishing LLC, Rapid City, SD.” All rights including professional, amateur, radio broadcasting, television, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved by Big Dog/Norman Maine Publishing LLC, www.BigDogPlays.com, to whom all inquiries should be addressed. Big Dog Publishing P.O. Box 1401 Rapid City, SD 57709 Shakespeare’s Next Top Fool 3 Shakespeare’s Next Top Fool FARCE. In this reality-TV show, fools compete for the title of Shakespeare’s Next Top Fool. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

Exploring Movie Construction & Production

SUNY Geneseo KnightScholar Milne Open Textbooks Open Educational Resources 2017 Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies? John Reich SUNY Genesee Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Reich, John, "Exploring Movie Construction & Production: What’s So Exciting about Movies?" (2017). Milne Open Textbooks. 2. https://knightscholar.geneseo.edu/oer-ost/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at KnightScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Milne Open Textbooks by an authorized administrator of KnightScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exploring Movie Construction and Production Exploring Movie Construction and Production What's so exciting about movies? John Reich Open SUNY Textbooks © 2017 John Reich ISBN: 978-1-942341-46-8 ebook This publication was made possible by a SUNY Innovative Instruction Technology Grant (IITG). IITG is a competitive grants program open to SUNY faculty and support staff across all disciplines. IITG encourages development of innovations that meet the Power of SUNY’s transformative vision. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks Milne Library State University of New York at Geneseo Geneseo, NY 14454 This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Exploring Movie Construction and Production by John Reich is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Dedication For my wife, Suzie, for a lifetime of beautiful memories, each one a movie in itself. -

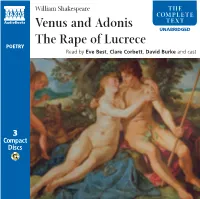

Venus and Adonis the Rape of Lucrece

NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 1 William Shakespeare THE COMPLETE Venus and Adonis TEXT The Rape of Lucrece UNABRIDGED POETRY Read by Eve Best, Clare Corbett, David Burke and cast 3 Compact Discs NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 2 CD 1 Venus and Adonis 1 Even as the sun with purple... 5:07 2 Upon this promise did he raise his chin... 5:19 3 By this the love-sick queen began to sweat... 5:00 4 But lo! from forth a copse that neighbours by... 4:56 5 He sees her coming, and begins to glow... 4:32 6 'I know not love,' quoth he, 'nor will know it...' 4:25 7 The night of sorrow now is turn'd to day... 4:13 8 Now quick desire hath caught the yielding prey... 4:06 9 'Thou hadst been gone,' quoth she, 'sweet boy, ere this...' 5:15 10 'Lie quietly, and hear a little more...' 6:02 11 With this he breaketh from the sweet embrace... 3:25 12 This said, she hasteth to a myrtle grove... 5:27 13 Here overcome, as one full of despair... 4:39 14 As falcon to the lure, away she flies... 6:15 15 She looks upon his lips, and they are pale... 4:46 Total time on CD 1: 73:38 2 NA432912 Venus and Adonis Booklet 5-9-6 7/9/06 1:16 pm Page 3 CD 2 The Rape of Lucrece 1 From the besieged Ardea all in post.. -

Equity Magazine Autumn 2020 in This Issue

www.equity.org.uk AUTUMN 2020 Filming resumes HE’S in Albert Square Union leads the BEHIND fight for the circus ...THE Goodbye, MASK! Christine Payne Staying safe at the panto parade FIRST SET VISITS SINCE THE LIVE PERFORMANCE TASK FORCE FOR COVID PANDEMIC BEGAN IN THE ZOOM AGE FREELANCERS LAUNCHED INSURANCE? EQUITY MAGAZINE AUTUMN 2020 IN THIS ISSUE 4 UPFRONT Exclusive Professional Property Cover for New General Secretary Paul Fleming talks Panto Equity members Parade, equality and his vision for the union 6 CIRCUS RETURNS Equity’s campaign for clarity and parity for the UK/Europe or Worldwide circus cameras and ancillary equipment, PA, sound ,lighting, and mechanical effects equipment, portable computer 6 equipment, rigging equipment, tools, props, sets and costumes, musical instruments, make up and prosthetics. 9 FILMING RETURNS Tanya Franks on the socially distanced EastEnders set 24 GET AN INSURANCE QUOTE AT FIRSTACTINSURANCE.CO.UK 11 MEETING THE MEMBERS Tel 020 8686 5050 Equity’s Marlene Curran goes on the union’s first cast visits since March First Act Insurance* is the preferred insurance intermediary to *First Act Insurance is a trading name of Hencilla Canworth Ltd Authorised and Regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority under reference number 226263 12 SAFETY ON STAGE New musical Sleepless adapts to the demands of live performance during the pandemic First Act Insurance presents... 14 ONLINE PERFORMANCE Lessons learned from a theatre company’s experiments working over Zoom 17 CONTRACTS Equity reaches new temporary variation for directors, designers and choreographers 18 MOVEMENT DIRECTORS Association launches to secure movement directors recognition within the industry 20 FREELANCERS Participants in the Freelance Task Force share their experiences Key features include 24 CHRISTINE RETIRES • Competitive online quote and buy cover provided by HISCOX. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994.